Signs Are Pointing to a Strong Midterm Environment for Democrats

December 2, 2025

As 2025 comes to a close, TLP will begin ramping up our coverage of next year’s midterm elections. With just over 11 months to go, all signs point to a favorable environment for Democrats. If the elections were held today, it’s a good bet that they would win back the House of Representatives, as they did the last time Trump was president. They may even flip one or two governor’s seats and a handful of state-legislative chambers.

Currently, however, it’s unclear just how strong a national environment they will enjoy next year, and whether it will be capable of lifting candidates in places that voted for Trump by significant margins in 2024. So today, we’ll take a look at where things stand across several key metrics and determine what we can glean from the data we have.

One sign of very real optimism for Democrats is the party’s performance in last month’s elections—specifically, in the races for New Jersey and Virginia governor. Yes, both states have voted blue at the top of the ticket for the better part of at least the last decade-and-a-half. But it was the fashion in which Democrats won that impressed:

-

In both contests, the Democratic candidates won by double digits;

-

They outperformed the party’s past nominees in both places dating back to 1993 in New Jersey and 1965 in Virginia, and their approximately nine-point over-performance of Kamala Harris was a stronger showing than Democrats enjoyed in 2017 versus Hillary Clinton in these states;

-

Turnout in each state also surpassed levels seen in the 2022 midterm election, a sign of very real enthusiasm among Democratic voters; and

-

Especially important: there is evidence in both the exit polls and post-election polling that the Democratic gubernatorial candidates won back small but meaningful shares of 2024 Trump voters.

It’s difficult to extrapolate from these results as we look forward to 2026 to guess what the national House popular vote margin might look like. In 2017, Democrats won the Virginia governor race by nine points and the New Jersey race by 13.5, but the following year they won the House popular vote by a smaller 8.4 points. However, the fact that Democrats’ margins in this year’s contests were larger than they were in 2017 portends a national environment that may well be at least as favorable as the one they experienced in 2018.

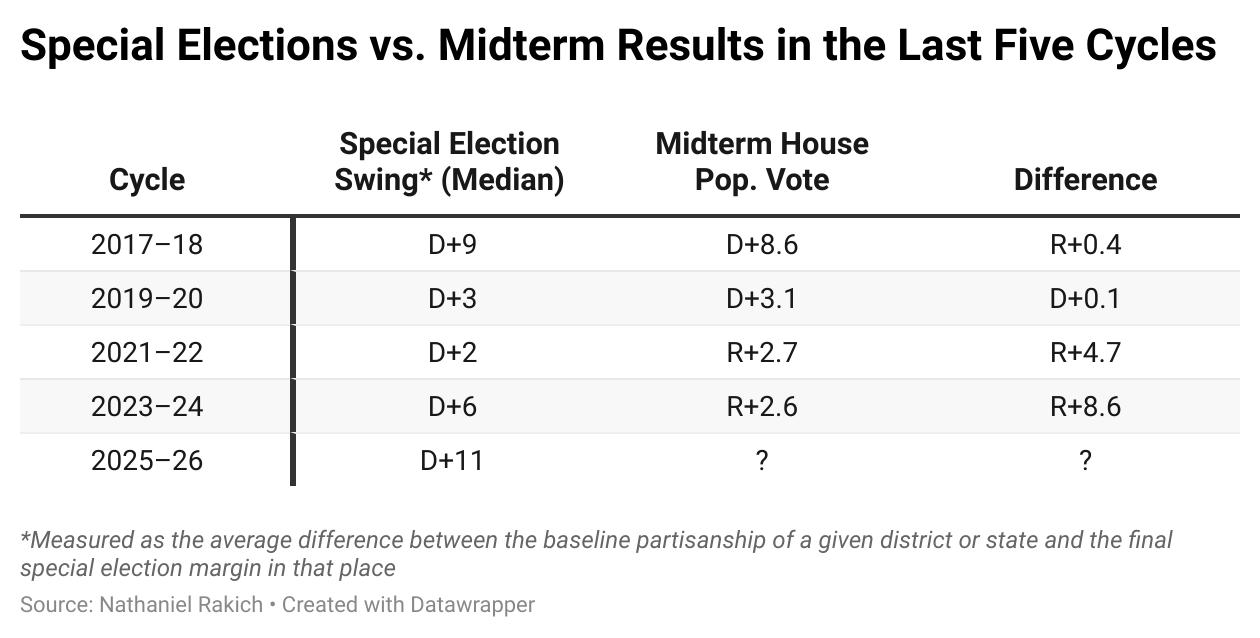

Perhaps the most hopeful sign for Democrats right now is their performance in special elections. According to data from election analyst Nathaniel Rakich, the median swing in states and districts with special elections this cycle (relative to the partisan baseline of those places) has been 11 points toward Democrats. In the Trump era, that is the largest swing for either party.

As the above chart shows, Democrats in the Trump era have routinely had an edge in these off-year elections, and yet that has not always translated to success in the subsequent general election. However, the last time the party came close to their current 11-point median swing was a nine-point margin in 2018—when, like now, they were the out-party looking to bounce back in a midterm at a time when Trump was president. Coupled with this year’s election results, this is a signal that Democrats are likely heading into a “blue wave” type of environment next year.

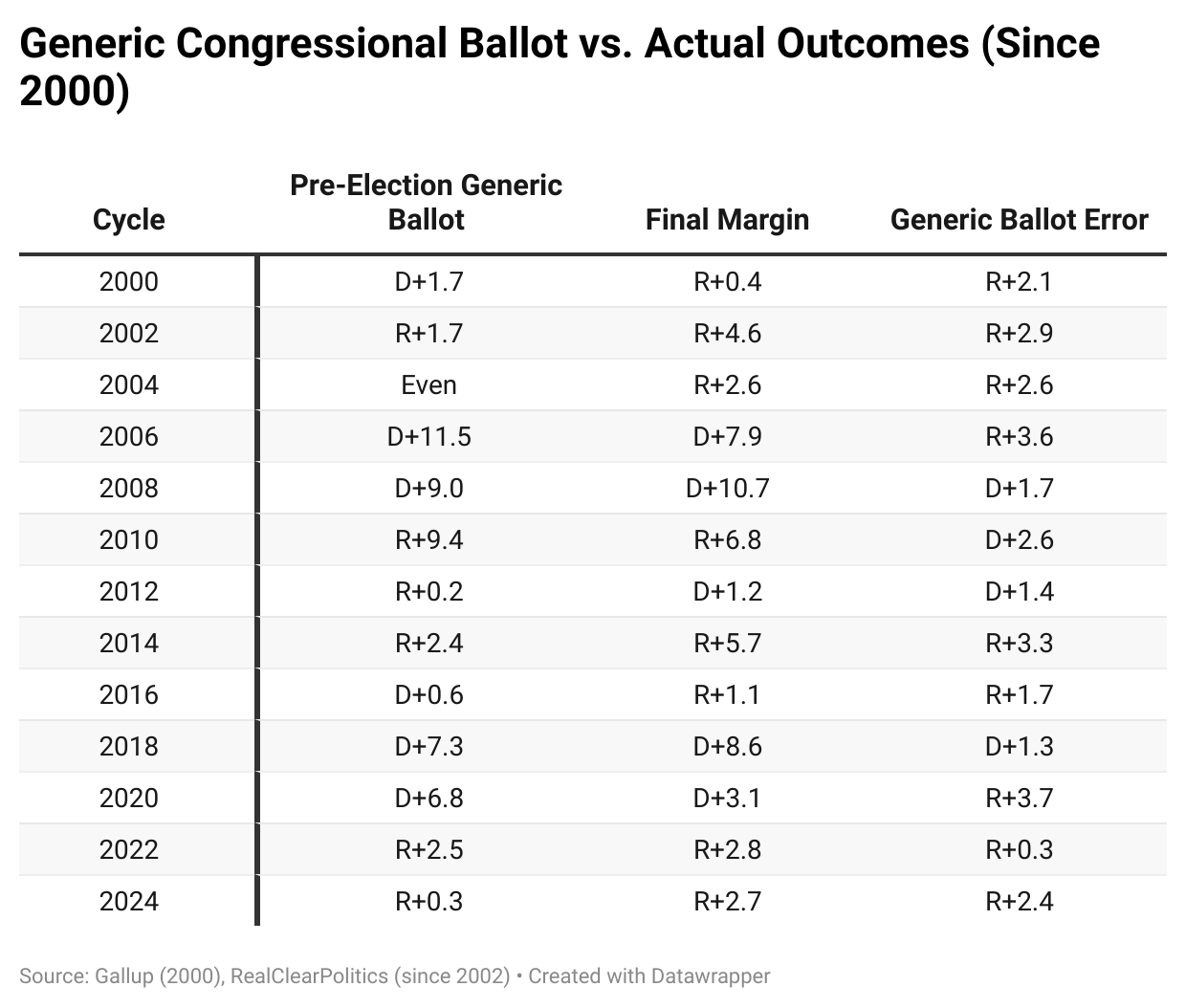

Perhaps the best tool available for gauging how the country is thinking about the midterms outside of actual election results is the generic congressional ballot (or GCB), a poll question asking which party Americans want to see control Congress in the upcoming election. As we have previously noted, these polls in recent midterm cycles have been predictive—as far as 18 months out—of not just which party is likely to have the advantage in the upcoming elections but sometimes even what their margin in the national House popular vote will be.

According to two differenttrackers, at the time of this year’s November elections the GCB was around three points in favor of Democrats (and their candidates in the most high-profile races far exceeded that). Since then, it has ticked up by a point or two. In another poll conducted by

, likely voters were pushed to pick one party or the other and gave Democrats a 7.6-point edge (53.8 to 46.2).

By comparison, though, around the same time in the 2018 cycle, the GCB already showed an 8.9-point advantage for Democrats. Moreover, the final margin that cycle indeed ended up being an almost identical 8.6 points. So, currently, even in their best-case scenario, Democrats are underperforming relative to their last big midterm as the out-party.

All this also suggests that the GCB has been a better predictor of the midterm picture than the 2025 elections or special elections that precede it.1 One of these two metrics will have to give come next November. It’s possible the Democrats’ advantages in the GCB will improve before then to match their other performances. But there is a world of difference between a national environment that mirrors this year’s (~D+15) or even 2018’s (D+8.6) versus one that is only D+4.

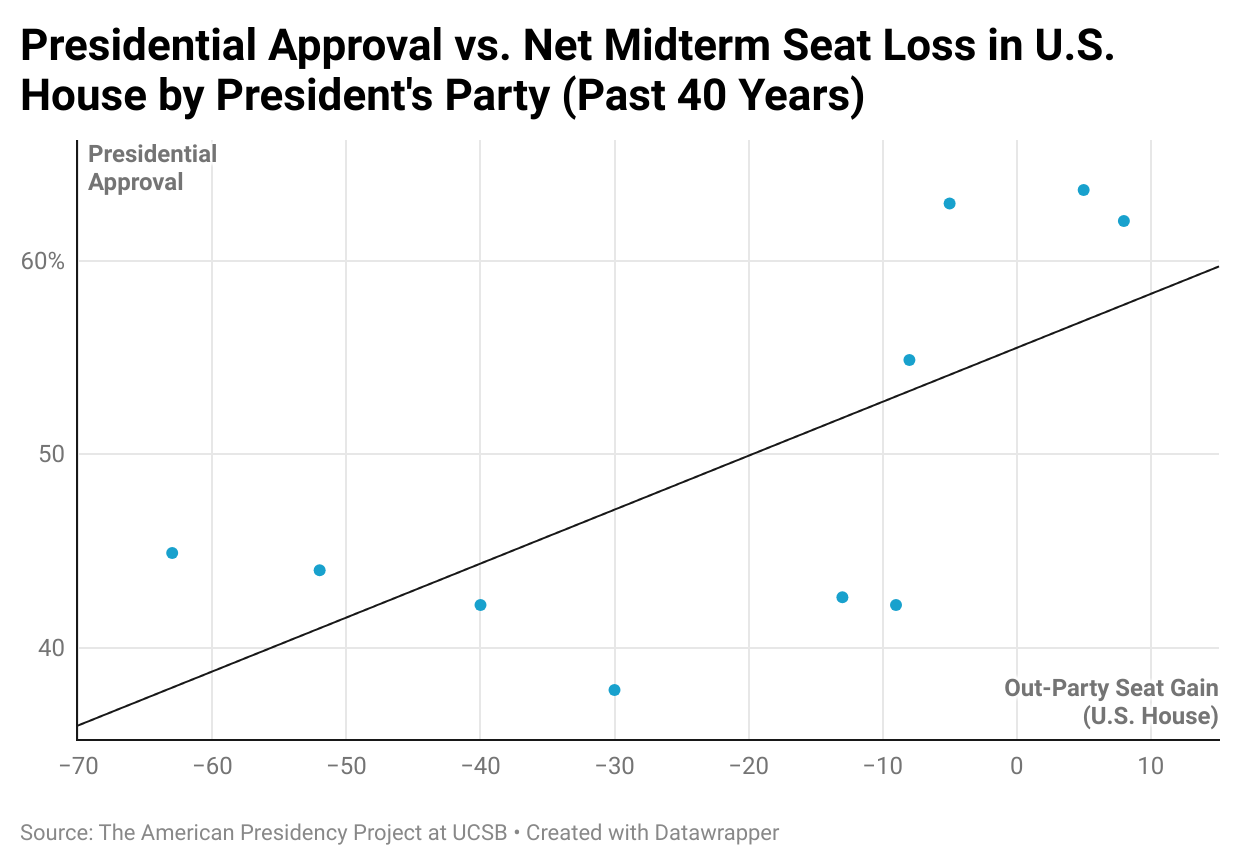

A quick reminder of how a president’s approval rating affects their party’s midterm prospects:

[One] strong historical predictor of midterm results is the approval rating of the incumbent president, which correlates highly with their party’s seat loss in the House. The only presidents in the polling era whose parties experienced a net seat gain in a midterm election (Bill Clinton and George W. Bush) enjoyed approval ratings north of 60 percent (66 percent and 63 percent, respectively). But even a strong approval rating doesn’t guarantee success for a president’s party. […]In his first term, Trump’s Republicans lost 42 House seats. Given the more constricted House map this time around, it’s very unlikely his party’s losses will be that deep next year, no matter his personal standing. However, a low approval won’t do them any favors…

Indeed, one phenomenon that has remained consistent in politics for decades: a poor approval rating for the president virtually guarantees his party will lose seats.

After a relatively stable period stretching from the beginning of July to mid-October, President Trump’s net approval rating has taken a hit, dropping from -7.6 percent on October 20 to -14.7 as of last week (though it has ticked back up slightly to -13.1 this week). This trend is evident at the issue level as well. On his best issue, immigration, Trump had been holding steady for much of the July to October period, with a net approval rating of around -3 percent. Over the past month, however, that dropped to -8.1 percent, the worst standing of his second term. He is in even worse shape on the economy, as his approval ratings on trade (-17.8), the economy (-21), and especially inflation (-34.1) have all slid.

It is possible that Trump, who has defied political gravity time and again, is now being weighed down by the six-year itch.

Much like presidential approval, the state of the economy can have a strong influence on election outcomes. A robust economy isn’t always a guarantee of success for the incumbent party, but a bad one—or at least one that voters believe is bad—almost always creates an unfavorable national environment for them. The problem for Trump and the Republicans is that there are few signs that any metric is better today than it was back in 2018, when they got shellacked, while several key things are worse.

On the surface, the economy today looks somewhat similar to that of 2018. Inflation has come down from its recent surge to just three percent today, though this is still higher than it was seven years ago (2.5). The unemployment rate is around 4.4 percent, up a bit from seven years ago (3.8 percent) but not terribly alarming.

The problem for Republicans, however, is that many voters still do not feel as though things have gotten better under their leadership, and many are worried about the future. According to the University of Michigan, the current consumer sentiment index, which gauges how consumers feel about the state of the economy, is just 53.6. For comparison, that figure was 98.6 in the run-up to the 2018 midterms.

We can see a similar story in a recent (and brutal) Fox News poll. Among the results:

-

Three-quarters (76 percent) of voters said that economic conditions today are either “only fair” (34 percent) or “poor” (42 percent, a plurality);

-

A strong plurality (46 percent) said they had been “harmed” by the economic policies of the Trump administration (for context, no more than 43 percent ever said the same about President Biden’s policies in Fox’s polling);

-

Sixty-two percent blamed Trump rather than Biden (32 percent) for current economic conditions;

-

A majority (52 percent) said inflation is “not at all” under control;

-

Majorities said their costs have gone up since one year ago for groceries (85 percent agreed), utilities (78 percent), healthcare (67 percent), housing (66 percent), and gas (54 percent); and

-

Perhaps worst of all for Republicans: 53 percent of respondents in the poll said they think Democrats have a better plan for making things more affordable than does the GOP (43 percent).2

In a September CBS poll, the top words Americans gave to describe the country’s economy were “uncertain” (61 percent) and “struggling” (54 percent). Sixty-seven percent expected prices to go up in the coming months.

These poor economic perceptions have already hurt Republicans in one election. As we discussed in our post-election analysis last month, voters in places like Virginia who believed the economy was not in good shape voted overwhelmingly Democratic. And as we established above, many are souring on Trump’s handling of the economy. According to Nate Silver’s latest aggregates, the president’s net approval on inflation, specifically, is deeply underwater, with just 31.3 percent of Americans approving against fully 65.4 percent disapproving.

If things don’t improve between now and next November, Republicans will likely be in for a world of hurt.

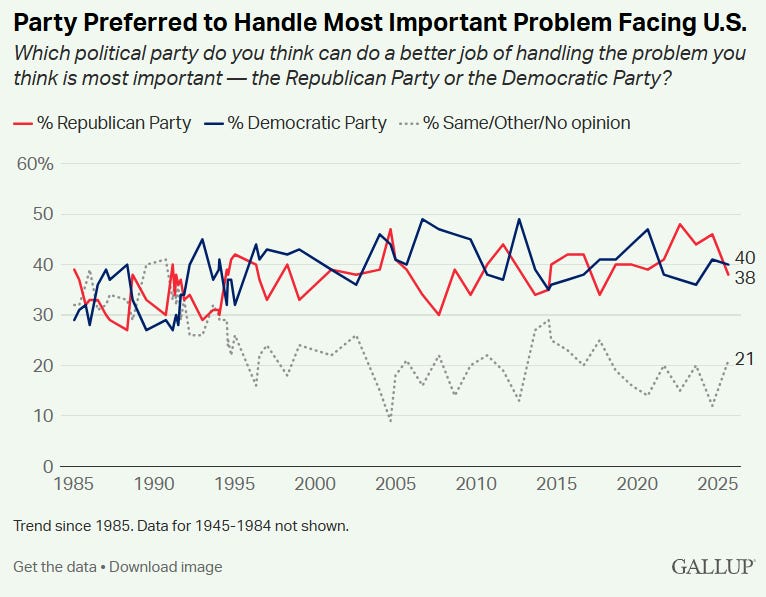

One of the most important predictors of Trump’s success in last year’s election came in pre-election polling from Gallup, which found that voters saw Republicans as the party “better able to handle the most important problem” facing America. Gallup considered this question to have a strong relationship to past presidential election outcomes—and it turned out to be prescient.

Fast-forward one year and that same indicator has now flipped. Whereas voters before the last election trusted Republicans over Democrats by a margin of 50 to 44 to handle the top issue, they now trust Democrats by four points, 47 to 43.

Polls from David Shor and The Argument have shown a similar reversal in the Democrats’ fortunes. According to the Argument’s Lakshya Jain:

We asked voters about their top two issues and, unsurprisingly, 60 percent of voters ranked “cost of living” as a top-two issue in our survey. But despite Trump’s tariff policy and the continuing frustration with high grocery and consumer-goods prices, Democrats won these cost-of-living voters by just under half a percentage point in our survey.

However, he adds:

Those numbers aren’t good for Republicans, but they’re a lot better than Trump’s nightmarish approvals on those issues are… This suggests that Democrats face real trust problems on the economy that haven’t really gone away yet, despite voters giving Trump exceptionally poor marks for his economic stewardship.

A year from now, Democrats may have a more robust trust advantage over the Republicans on handling the economy, but they still have work to do to restore that trust following four years in with which many voters were left feeling completely dissatisfied with the party’s leadership on this issue.

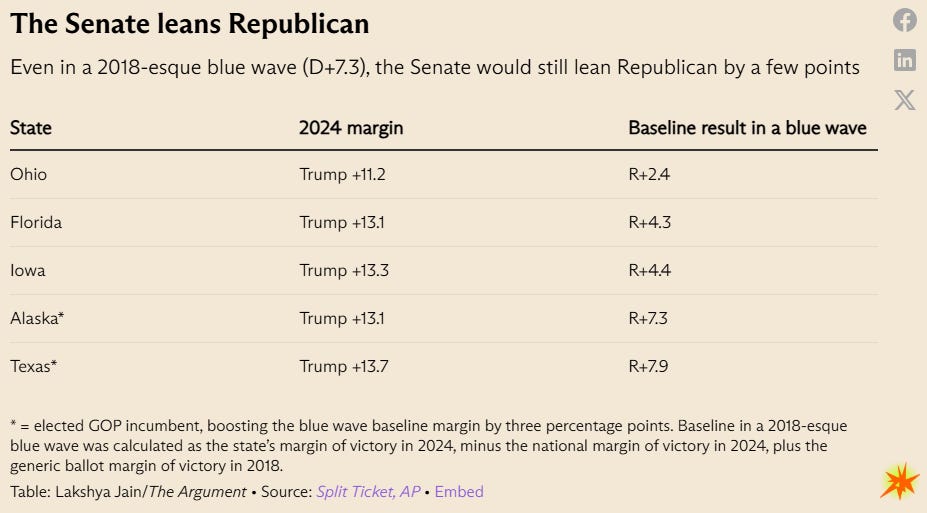

Overall, the picture looks promising for Democrats ahead of next year. However, we want to end with an obligatory note of caution, specifically, regarding the Senate. In a world in which the national environment mirrors 2018, Democrats can expect to successfully defend all of their Senate seats and likely flip two of Republicans’: Maine and North Carolina. But beyond those, they will be forced to win seats in states that voted for Trump by at least 11 points last year, such as Iowa, Ohio, and Texas. And that means the party will need an even stronger national environment than they had in 2018 to win back the majority.

Jain put together a helpful graphic showing what the outcomes in these types of Senate races would look like if Democrats merely repeat their last “wave” performance:

This is why we at TLP write so often about the need for Democrats to address their structural issues. Winning big in midterm and other off-year elections delivers real benefits for the party—namely, they gain power and subsequently get to wield it. But three of the most important institutions in American politics—the presidency, Senate, and Supreme Court—will become harder to capture over time if they can’t address their longstanding weaknesses and become more competitive in right-leaning places.

Though the GCB test has become more accurate since 2006, it should be noted that that cycle—the last time a two-term GOP president faced a midterm election—it overestimated the Democrats’ advantage by 3.6 points.

Lest readers think this is just a skewed sample, the same poll found that these respondents also trusted Republicans over Democrats to secure the U.S. border (63 to 34 percent) and deal with illegal immigration (56 to 40 percent).

Search

RECENT PRESS RELEASES

Related Post