Cobalt mining for green energy risks women’s reproductive health in DRC

November 17, 2024

- In the Democratic Republic of Congo, industrial and artisanal mining of cobalt and copper, essential for battery-powered technologies, poses risks to the reproductive health of women, preliminary research suggests.

- Sources in the Golf Musonoie region of Kolwezi, the “world’s cobalt capital,” highlight a rising number of cases involving birth defects , stillbirths, infant deaths shortly after birth, and infections.

- The scientific community doesn’t yet know to what extent the extraction process affects reproductive health, but suspects include the radioactive uranium found in ores, as well as the pollution from mining waste and chemicals in the water.

- Mongabay investigated and collected testimonies from women residents in the affected regions.

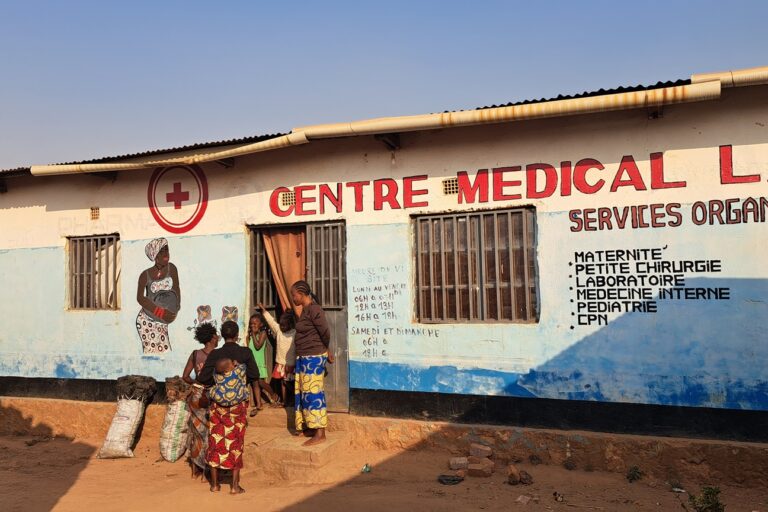

LUBUMBASHI, Democratic Republic of Congo — Our investigation begins at the Trinité Medical Center, less than 20 kilometers, or 12 miles, from the city of Kolwezi, in the south of the Democratic Republic of Congo. Just 100 meters (330 feet) away, a copper and cobalt industrial mine operates right next to people’s homes. The dust from the mine is kicked up by passing trucks loaded with ore and settles into the houses, even reaching as far as the health center.

Sometimes, when the company guards are chasing illegal immigrants out of the mine, they throw projectiles that reach the medical center,” says Julie Nshinda, a nurse who runs the center.

The sun blazes intensely while we’re reporting on Monday, July 22, 2024. We take a winding path that runs along the long concrete wall surrounding the huge open-air copper mine owned by the company COMMUS (Compagnie Minière de Musonoïe), a subsidiary of Zijin Mining, a multinational mining company headquartered in China. The area bustles with activity as vans loaded with bags of ore, extracted from the mine’s backfill by local artisanal miners, head off to be sold elsewhere.

Higher up, heavy vehicles circulate: COMMUS dump trucks loaded with the same material. Later, workers and machines will crush these stones in the mining factory and transform them into copper ingots and a greenish powder: cobalt, a critical mineral in the lithium-ion batteries that power computers to renewable energy technologies.

Welcome to the Golf Musonoie, a neighborhood next to downtown Kolwezi, also known as the world’s cobalt capital.

‘I’ve had four miscarriages’

Julie Nshinda has witnessed many cases of sexually transmitted infections and, more seriously, congenital malformations in babies and miscarriages. During our visit to her center, she shows us images of a baby with internal organs protruding from their belly. Her medical center receives five to 10 women per month with reproductive health complaints, she tells Mongabay.

A week after our visit, Nshinda reported (with photographic evidence) the birth of a baby with their brain protruding from their forehead. Witnessing these shocking stories and events, especially for couples and mothers, Nshimba decided to speak out against the pollution, which she says originates from COMMUS’s mine.

“I see a lot of cases of threatened miscarriages and premature births. Sometimes, a pregnant woman arrives, complaining of abdominal pain. When I do an examination, I can see that the fetus is already dead and starting to decompose. There are also cases of genital infections. Here, for example, I have this young woman lying on the bed, bleeding profusely,” says Nshinda.

We contacted COMMUS and Zijin Mining for their response to pollution accusations and the mine’s proximity to the homes. Neither company had responded by the time of publication.

In their report titled “Environmental impact of mining in the DRC,” published in March 2024, the U.K.and DRC NGOs RAID and AFREWATCH, which specialize in natural resources, say that “the scientific community is still unclear about the extent to which frequent contact with water contaminated with copper and cobalt mining waste, sulfuric acid and heavy metals specifically affect women’s health.”

However, they state that it’s well known that poor hygiene practices, due to the lack of access to drinking water and sanitation facilities, put women and girls at risk of infections, as well as other gynecological and reproductive diseases.

https://youtube.com/watch?v=xWt-4U54Y68&si=wGByO7x8SubjJYGr

According to the report, 56% of respondents said they had noticed a significant increase in gynecological and reproductive problems among women since the start of industrial mining activities in the region, with the exact periods varying depending on the region visited.

“I have had four successive miscarriages in the last few years. When I reach three months of pregnancy, I start feeling pain in my lower abdomen. And then the pains get worse, and I lose the baby. Every time I conceive, the same thing happens. It’s hard,” says Angèle, a woman working in the Kolwezi artisanal mines, in the south of the DRC.

Angèle is in her 40s and lives in Postolo district, less than 1 km (0.6 mi) from the COMMUS industrial mine in Kolwezi. She has worked in the Chabula artisanal mine near the city for 16 years. Her husband, who died four years ago, was also an artisanal miner.

For Angèle, the health problems she’s experiencing could be linked to her work in the artisanal mine.

Standing in the water, handling ore with their bare hands

Illegal artisanal miners extract copper and cobalt from COMMUS’s mining residues. Like hundreds of other women living in Kolwezi, home to some of the world’s largest cobalt reserves, Angèle buys minerals from the miners and resells them to distributors, whose buyers are mainly of Chinese and Indian origin.

“In recent years, manufacturers have been cautious about purchasing products from artisanal mines for their stock,” she says. “However, the practice persists through intermediaries or anonymous buyers.”

In Kapata, a 20-minute drive outside Kolwezi, hundreds of women work cleaning ore at another artisanal mining site. It’s a low-paying job at the end of the artisanal mining chain, compared to the work of diggers who descend into the tunnels they excavate. Women aren’t allowed in these tunnels, based on the belief among artisanal workers that their presence would drive away the copper veins.

The women spend anywhere between eight and 10 hours a day cleaning the unearthed ores. With their feet in the water, they handle black stones, generally with their bare hands, knowing practically nothing about the possible radiation danger. The most capable workers can earn between 20,000 and 100,000 Congolese francs per day, roughly $6 to $35.

According to such as Queenter Osoro of Kenya’s Nuclear Power and Energy Agency and chair of the East African Association for Radiation Protection, and a French scientist who requested to remain anonymous, the radiation levels can be high in certain rocks. Copper and cobalt can “contain small amounts of uranium and thorium, which decay into highly radioactive elements,” Osoro says.

She adds that radiation contamination, whether from industrial or artisanal mines, can spread into rivers. Refinery workers can also be exposed to the residue, which can contain “radium from the radioactive decay chain of uranium, which is toxic and radiotoxic if ingested.”

Similarly, the presence of uranium generates radon, a chemical element, upstream of this decay chain, which is also harmful if inhaled in large quantities, according to the French expert.

In April 2024, the DRC government suspended production at the COMMUS mine due to suspicions of high radioactivity in the extracted ores. Several trucks had been returned from Southern Africa to the DRC due to high levels of radioactivity. This suspension was reversed less than a month later.

However, the risk is particularly high in artisanal mining, where long-term exposure is compounded by factors such as dust, poor ventilation, and lack of protective equipment. Some artisanal workers even work topless.

The women we met in Kapata, who clean the ores or frequently sit on sacks of ore they purchase, report experiencing tickling sensations in their genital areas.

“Sometimes, we get rashes,” says Suzanne Ngwewe, who supervises the women cleaning ores. However, the ore cleaners she supervises at the national mining cooperative that employs her must strictly adhere to a specific dress code before starting work.

Rivers polluted

The women we spoke to in the Golf Musonoie say their reproductive health issues are linked to mining activities for the energy transition. This is certainly the view of Julie Nshinda, the nurse at the Trinité Medical Center. Before COMMUS arrived int he area, she didn’t get as many patients presenting with these problems.

“When the health center was created, I treated more patients with malaria, coughs, simple fevers and typhoid. But since mining intensified [in 2019], I have been dealing with other pathologies, especially among women of childbearing age,” Nshinda says.

Some women contract these health problems from the rivers they work in while cleaning the ore. Researchers from the toxicology department at the University of Lubumbashi are seeing this in their studies. RAID and AFREWATCH commissioned an investigation into the impact of industries in the DRC on the surrounding areas. Water, air and soil samples were taken, but the final report and laboratory results are still pending.

Preliminary results from the March 2024 analysis showed that there’s acidifying industrial pollution in the water, says Célestin Banza Lubaba, director of the toxicology unit at the University of Lubumbashi. He says there’s a link between mining and reproductive health problems, but adds he’s still waiting for the full results of the ongoing analyses.

“The first result shows the degradation of watercourse quality. In the Democratic Republic of Congo, bad water quality is a common issue,” Banza says. “Most companies discharge toxic waste directly into watercourses, which destroys biodiversity and habitats. Many watercourses are significantly impacted by pollution in southern Katanga in Lualaba province,” where Kolwezi is located.

The preliminary results indicate several sexual and reproductive health impacts, including sterility. In high enough concentrations, various metals can enter the human body through inhalation, ingestion or through the skin, Banza says.

He cites lead as an example from the copper metal family, noting that it’s neurotoxic and that this toxicity even affects blood formation and can cause anemia. The toxicity of metals can even “disrupt gametogenesis, that is, the formation of gametes” or sex cells, Banza says.

An issue authorities are aware of

Peter Kalenga, an official with the Luabala provincial mining agency, says he’s aware of Musonoie residents’ complaints and that his department is investigating the issue.

“We are taking these complaints very seriously,” Kalenga tells Mongabay. “We have received other complaints from people on Yohwe and Mai-Ndombe avenues in Musonoie, regarding structural cracks and their houses sinking. This is on top of the air pollution caused by the elevation of the COMMUS embankment.

“We are working on the case. A report has already been submitted to management,” he adds.

Mining regulations clearly define mining companies’ obligations in the DRC. Kalenga says the directorate for mining environmental protection must ensure the implementation of “techniques and measures to mitigate the negative effects of mining operations on ecosystems and populations, as well as techniques for rehabilitating environments affected by mining activities.”

However, according to NGO members, the problem lies in the application and monitoring of the mining regulations. Some civil society sources suggest that regulatory officials are often prevented from doing their work or are corrupted. Mining companies can easily become politicized in a resource-dependent economy where public or corporate figures wield significant influence, they say.

Gécamines, the largest DRC mining company, previously owned the COMMUS mine. Until 2006, Gécamines had a monopoly on copper and cobalt production, the main minerals produced in the region. Since 2015, many of Gécamines’ deposits have been sold to private companies, most of them Chinese. In the COMMUS case, Gécamines is the minority (28%) shareholder, while Zijin Mining Group Ltd. holds the majority stake (72%). According to Zijin Mining, the mine produced 129,000 metric tons of copper and cobalt in 2023, using “China’s advanced approach to ecological preservation, receiving widespread praise from the DRC government and local communities.”

Zhejiang Huayou Cobalt was also a shareholder in COMMUS before 2017. A 2016 report by Amnesty International singled out the Chinese company, particularly for its lack of due diligence between the mining and distribution steps in the supply chain.

The same report also indicated that Chinese and South Korean companies specializing in the production of lithium-ion batteries were major customers of Zhejiang Huayou Cobalt’s products: Toda Hunan Shanshan New Material, a subsidiary of Ningbo Shanshan Co. Ltd. (Ningbo Shanshan); L&F Material Co. (L&F), a South Korean firm that accounted for 13.16% of Zhejiang Huayou Cobalt’s sales; and Tianjin Bamo Technology Co. Ltd. (Tianjin Bamo), a Chinese supplier of battery materials.

According to the report, Samsung SDI and LG Chem, two of the world’s largest battery manufacturers, were interested in some of Zhejiang Huayou Cobalt’s cobalt products. However, Samsung has categorically denied any connection between the two.

Protection initiatives in Kolwezi

Some stakeholders recognize the risks involved around mining sites, particularly for women. In Kolwezi, the Mining Cooperative for Social Development (CMDS), which oversees more than 6,000 artisanal miners at the Kamilombe site some 10 km (6 mi) from the city, provides women with personal protective equipment. The program is supported by the Fair Cobalt Alliance, says Marie Kulemba Samba, the social department manager at CMDS. Fair Cobalt Alliance is an initiative founded by Fairphone, Signify, Zhejiang Huayou Cobalt and The Impact Facility with the aim, among other things, of promoting responsible cobalt production.

“We have purchased personal protection kits for the women who clean the ores from our quarry,” Kulemba Samba says. “The kits contain a waterproof suit and plastic boots. No woman is allowed to clean the cobalt ore without this PPE.”

The cooperative also reminds the women of other health protection measures every morning. These include the requirement to wear appropriate clothing under the PPE, a prohibition on sitting on bags containing ore, and a reminder to consult with a doctor whenever they have health problems.

Women working in other artisanal mines say they want these protection measures extended to all mining sites. Support is essential to guarantee their health protection and promote “clean” cobalt production, they say.

For Aimée Manyong, president of the Mining Cooperative for the Promotion of Women, which campaigns for women’s rights, particularly in the artisanal sector, there’s an urgent need to find ways to protect women so that they can continue to benefit from the mines.

“We cannot just ask women to leave the mines,” she says. “It serves as a source of income for families. Not all women who come to the mining sites are illiterate; some are educated. Due to a lack of employment opportunities, they have turned to the artisanal mining sector as a means of economic empowerment.

“Asking women to leave the mining sector would be unfair,” Manyong says. “We should instead look at the support and security mechanisms in place on mining sites.”

Banner image : Women wearing protective gear. Screenshot from Mongabay Africa video.

Impunity and pollution abound in DRC mining along the road to the energy transition

FEEDBACK: Use this form to send a message to the author of this post. If you want to post a public comment, you can do that at the bottom of the page.

Search

RECENT PRESS RELEASES

Related Post