Energy storage in old mines could be the next big industry in the U.P.

November 22, 2024

NEGAUNEE, MI – Michigan’s Upper Peninsula may be primed for a major hydroelectric future because of its underground mining past.

Scientists at Michigan Technological University in Houghton believe it may be possible for hundreds of abandoned mines scattered across the U.P. to be transformed into pumped water storage facilities – a type of renewable, hydroelectric power generators.

City officials in Negaunee hope their hometown mine, the Mather B, may be the first of what could become a valuable new economic sector for U.P. communities. They already participated in a mine mapping project to propel research of the technology.

“Upper Peninsula-wide there are numerous underground mines that could possibly utilize that pumped storage hydro technology and that would provide more energy security for the Upper Peninsula and possibly lower prices for energy up here in the U.P.,” said David Nelson, Negaunee city planner. “Our energy costs up here are some of the highest in the nation.”

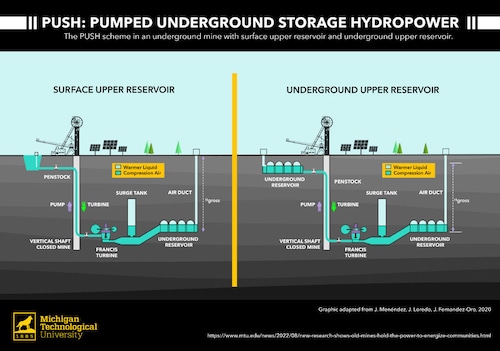

Pumped underground storage hydropower systems work by moving water between reservoirs at different elevations, so electricity can be generated as water moves down through a generator turbine. The systems are designed to work much like batteries to store energy – just smaller versions of the Ludington Pumped Storage Power Plant on Lake Michigan.

When energy is plentiful, water is pumped from a lower level to a higher, storing its potential energy. When energy is in demand, the water is released to flow back down to the lower level, turning electricity-generating turbines as it flows.Michigan Technological University

The idea is to retrofit old mining shafts to create fully contained underground water reservoirs at different depths. During low customer demand periods, electricity from the power grid could be used to pump water into the upper reservoir, whether it comes from renewable, nuclear or other sources.

Then during peak energy demand times, the water could be released back down through underground turbines to generate a type of hydroelectricity.

Scientists suggest Michigan may be well positioned to offer this energy storage concept to smooth out the peaks and valleys of supply and demand on the broader electric transmission and distribution grids.

“Because of the concentration of mining in the southern Lake Superior region – Minnesota, Wisconsin and Michigan – that whole area stands in a really interesting location between the Great Plains to the north and west, and the Great Lakes and the population centers to the south, where you can be generating and moderating the flows of power on a regional grid very effectively,” said Timothy Scarlett, associate professor at MTU.

Abundant renewable wind energy from the Plains could be imported into the Great Lakes and stored in pumped water systems in old mines, then released onto the grid when needed.

Scarlett further argued that building renewable energy infrastructure in brownfield spaces, like the old copper mines in the U.P., takes pressure off the need to build renewable energy like solar panels or wind turbines on undeveloped lands.

Michigan Tech researchers Roman Sidortsov and Tim Scarlett are seen at the Quincy Mine near Hancock, Michigan, in this 2022 file photo. While their study centered on the Mather B Mine in Negaunee, the findings are applicable to hundreds of hard-metal mines across the nation and the world.Michigan Technological University

Roman Sidortsov, fellow MTU associate professor of energy, said a big hurdle to the potential new industry is there are missing data about underground depths and layout of various types of old mines across the nation. Yet another great challenge is that this technology has never before been built in old, retrofitted mining shafts, he said.

“It’s not an easy thing to develop, not because of the technology, because the technology has been in existence for over 100 years, effectively. So, it is because you are dealing with a hodgepodge of issues that have never really been tackled altogether,” Sidortsov said.

“The biggest complication, in my view, is not even the logistics of trying to develop this project. It is dealing with the overarching legal and regulatory regime.”

Multiple layers of state and federal regulatory agencies would need to sign off on such a multi-faceted energy project.

That’s why the scientists want a pilot project as the next feasibility step for future commercial investment, though there are pumped water mine storage projects already under development in Sweden.

Wisconsin-based Dairyland Power Cooperative is collaborating with the researchers at MTU and in Sweden to explore the potential for using old mines in the Upper Midwest for pumped storage hydropower. But there’s no pilot project yet.

The mine storage system brings unique benefits, as it “essentially recycles an existing, but unused, site into a flexible, carbon-free power storage system without some of the environmental concerns of traditional battery storage,” previously said Dairyland President Brent Ridge, in a statement.

Yet the concept is a solid one, said an expert at the nation’s largest multi-program science and technology laboratory.

Part of the reservoir, left, at the Ludington Pumped Storage Plant on Monday, July 10, 2023. The hydroelectric plant and reservoir, built between 1969 and 1973, is owned jointly by Consumers Energy and DTE Energy and operated by Consumers Energy. Lake Michigan can be seen in the background. (Cory Morse | MLive.com)

Cory Morse | MLive.com

Scott DeNeale, a water resources engineer at Oak Ridge National Laboratory in Tennessee, said not only would this concept work, but the old mines of Michigan and the Upper Midwest may offer a significant advantage over other types of mines in other parts of the country, like the coal mines of Kentucky and Tennessee.

“There’s a lot of hard rock mines up in Michigan that probably do have … better structural integrity to them to where they can maybe not need quite as much structural reinforcement,” DeNeale said.

“You would want to line the reservoir … to make sure that, from a geotechnical standpoint, that the water is going to be able to be retained without seeping or the structure just falling apart.”

DeNeale also agreed with the Michigan scientists that a demonstration project would help launch this as a new industry and said there’s a lot of momentum in energy storage technology.

“The need for energy storage was yesterday. And you can build a ton of batteries, but the mine site, I think, is definitely an interesting spin on it,” he said.

The National Renewable Energy Laboratory reported that this type of closed-loop pumped storage hydropower system has the lowest potential to add to the problem of global warming among all energy storage options.

Energy experts argue that developing more energy storage capacity across the U.S. is necessary to pair with renewable energy sources like solar and wind, which can fluctuate with the weather. Storing excess energy during peak generation periods allows the electricity to be used later when renewable generation is low, creating overall better grid stability.

Renewable energy comes from sources that do not create greenhouse gas emissions, which are responsible for global warming and climate changes.

Related articles:

On Lake Michigan, a giant water battery aids clean energy transition

Historic hydro plant powering eastern U.P. critical for energy transition

Search

RECENT PRESS RELEASES

Related Post