Japan’s persistent fossil fuel subsidies threaten industry competitiveness and decarbonization goals

September 23, 2024

In August 2024, Japan resumed government subsidies for electricity, gas, and petrol bills, aiming to curb inflation that reached its highest level in over a decade in 2023. While these subsidies provide a short-term stopgap measure to combat rising consumer prices, they also perpetuate one of the root causes of inflation: Japan’s overdependence on imported fossil fuels.

The subsidies not only encourage the consumption of expensive coal, gas, and oil imports but also delay the transition to cheaper renewable energy and contradict the country’s goal to achieve net-zero carbon emissions by 2050.

Ultimately, a more coherent long-term inflation strategy would redirect subsidies toward investments in renewable energy to improve Japan’s energy self-sufficiency, primary balance, and industrial competitiveness.

An economic perspective on government subsidies

Since 2022, the Japanese government has allocated ¥11 trillion (US$77 billion) to subsidize electricity, gas, and petrol bills. In just two years, the petrol subsidy alone has cost ¥6 trillion (US$42 billion), dwarfing annual revenues from Japan’s tax on carbon-intensive imports. These subsidies in two years already constitute half the government funds allocated to decarbonization through climate transition bonds for the entire decade.

At the same time, Japan’s budget deficit has ballooned. Since 2020, spending has increased due to economic stimulus measures, resulting in more government bond issuances. Public expenditures, 30% of which are funded by government bonds, have been at a peak for 11 consecutive years, and Japan’s outstanding debt is the highest among industrialized countries.

Additionally, the country’s continued reliance on imported fossil fuels, alongside a weakening Japanese yen, caused the trade deficit to hit a record high of over ¥20 trillion (US$140 billion) in 2022. Prolonging fossil fuel subsidies worsen these economic issues and negate any benefits of addressing climate change.

Power sector subsidies reduce the incentives to transition to renewable energy

Despite Japan’s target to reduce fossil fuel consumption and transition to renewable energy, recent subsidies are likely to have the opposite effect. Currently, thermal power generation accounts for around 70% of Japan’s electricity supply. The country’s 6th Strategic Energy Plan aims to reduce this to 41% by the financial year (FY) 2030. In 2022, however, thermal power’s share had not declined from the previous year at 72.8%. Subsidies mask the actual cost of power generated from imported fossil fuels, reducing incentives to switch to cheaper renewable energy.

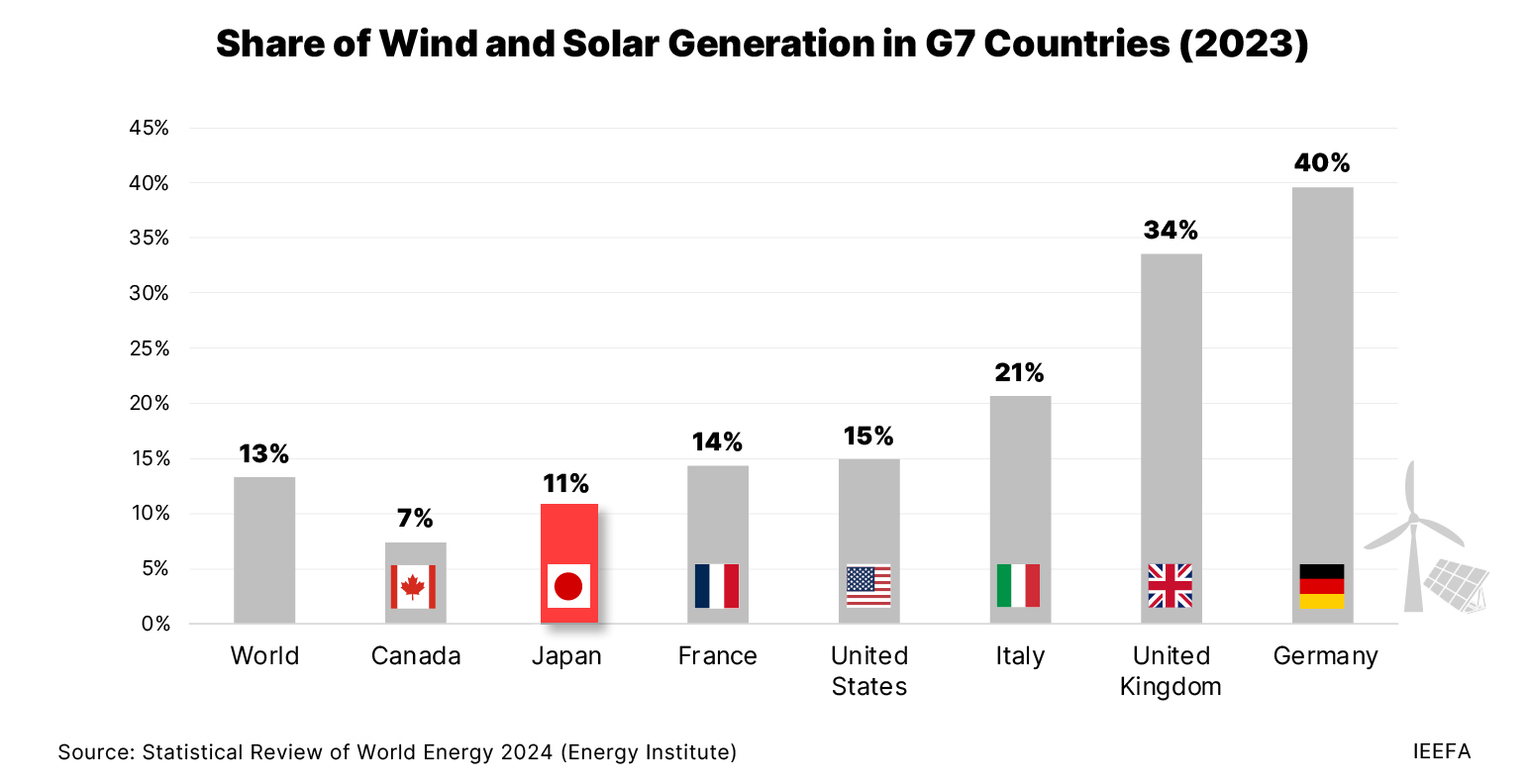

Along with Canada, Japan has the lowest expansion of renewable energy capacity planned by 2030 of the Group of Seven (G7) countries, following the COP28 pledge to triple renewable energy capacity. In 2022, Japan’s renewable energy share was only 21.7%, a 1.3% increase from the previous year and far behind the global average of 30%.

Although Japan’s solar capacity increased quickly following the introduction of a feed-in tariff in 2012, deployment has slowed since the tariff was phased out in 2019. Furthermore, Japan plans to build 5.7 gigawatts (GW) of offshore wind power by 2030 but has only built 0.15GW so far.

Japanese companies are increasingly concerned about the low capacity of renewable energy and missing out on the economic benefits of such energy. 87 Japanese companies are members of RE100, a global initiative of over 400 companies aiming to meet 100% of their electricity demand with renewable sources by 2050. These companies called on the Japanese government to triple its renewable energy capacity by FY 2035. However, the country has the lowest rate of renewable energy use among RE100 G7 companies at just 25%. As the global demand for environmentally friendly corporate practices grows, Japanese companies risk being left behind, particularly as the supply of renewable energy remains limited.

Transportation sector subsidies contradict decarbonization goals

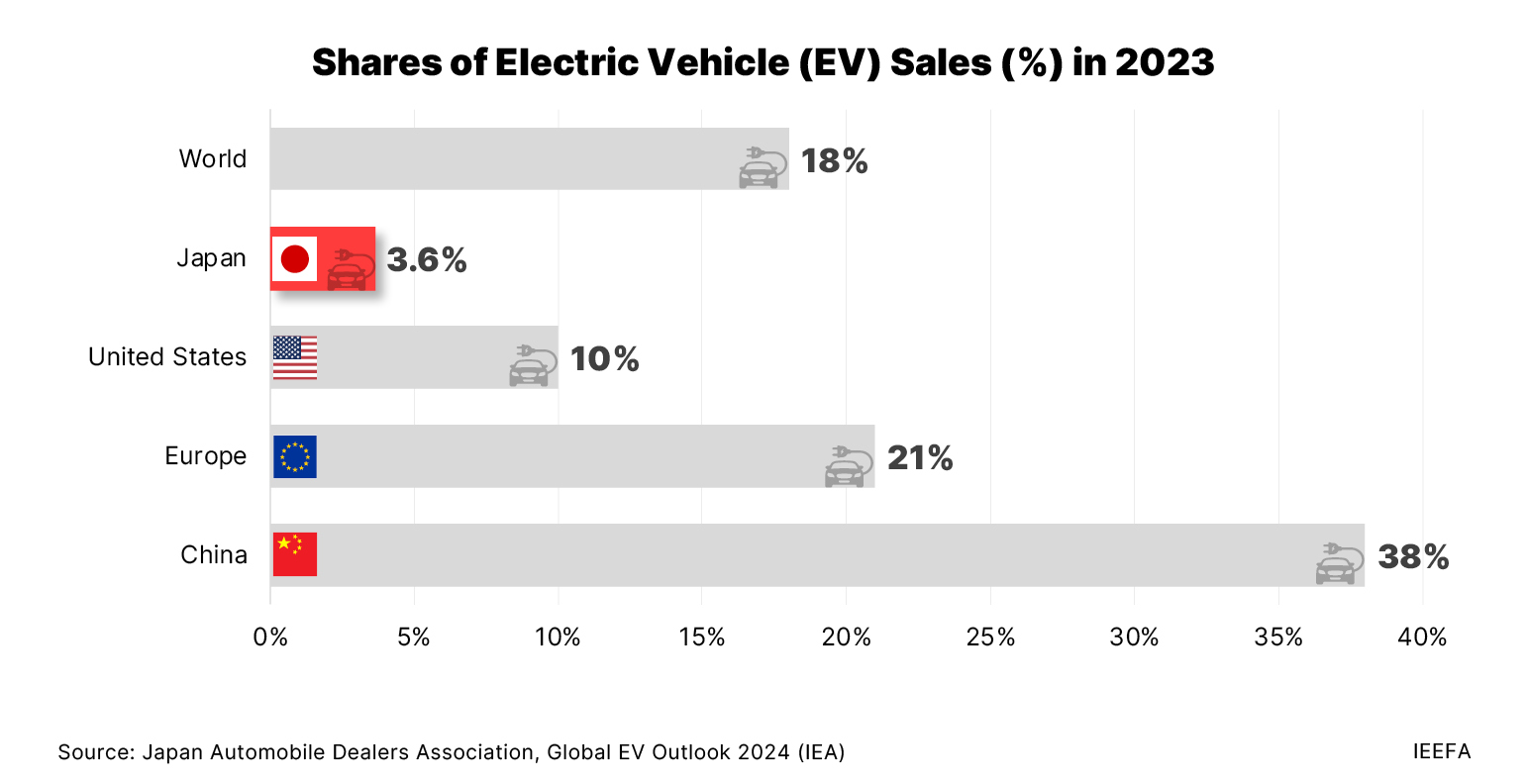

Petrol subsidies also conflict with decarbonization in Japan’s transportation sector, which accounts for 19% of the country’s carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions. The government aims to reduce transport emissions by 35% by 2030, but sectoral emissions increased in 2022 from the previous year. Moreover, just 3.6% of vehicles sold in Japan were zero-emission, compared to 18% of new car sales globally.

Japan’s failure to keep pace with the global Electric Vehicle (EV) trends undermines its decarbonization efforts and risks eroding the global competitiveness of its automotive industry, which accounts for over 17% of the country’s total exports. In 2023, China overtook Japan as the world’s largest car exporter due largely to higher shipments of Chinese EVs.

Petrol subsidies deprive Japanese consumers of incentives to switch to EVs, demonstrating how efforts to contain inflation can challenge the country’s clean energy targets. Without domestic sales incentives for EVs, car manufacturers may lose competitiveness in international markets.

Expectedly, EVs charged on an electricity grid dominated by fossil fuels will negate many of the climate benefits of EV adoption. Transportation and power sector decarbonization go hand in hand, but ongoing fossil fuel subsidies contradict both.

Investment in renewables will help Japan’s industrial competitiveness and decarbonization

Fossil fuel independence, renewable energy capacity expansion, and transport sector electrification are essential goals for Japan to achieve net-zero emissions by 2035. Japan’s ongoing electricity, gas, and petrol subsidies are counterproductive to its decarbonization goals and burden its primary balance. Reallocating these funds towards renewable energy investments and reducing dependency on fossil fuels could resolve Japan’s budget deficit and aid Japanese companies that may be exposed to increased risks in the rapidly evolving green global economy.

Search

RECENT PRESS RELEASES

Related Post