Looking at 2025, Climate: Bleak forecast, adaptation way forward

December 25, 2024

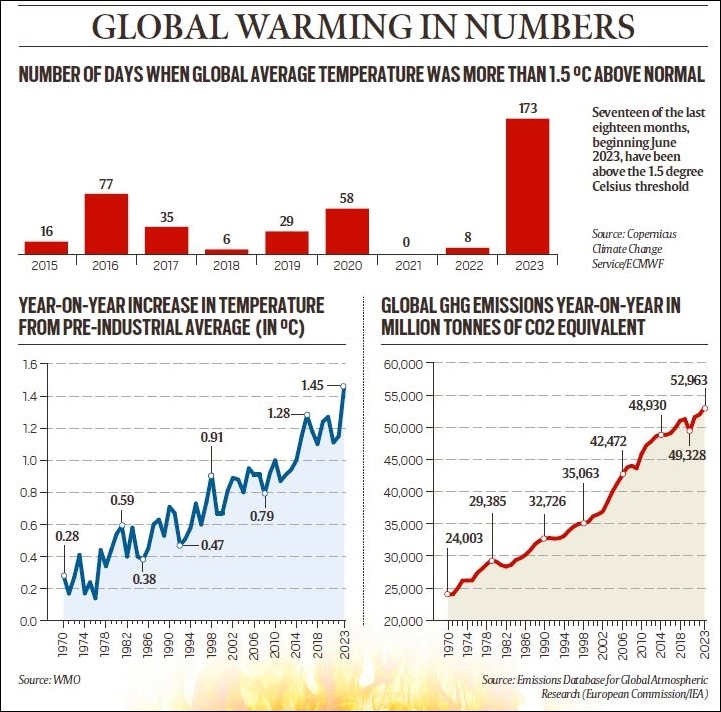

The year 2024 was when the world all but gave up on its effort to restrict global warming within 1.5 degree Celsius from the pre-industrial average, one of the key goals of the 2015 Paris Agreement on climate change. Ironically, 2024 is also set to emerge as the year when the annual average global temperature breached the 1.5 degree Celsius threshold for the first time.

There is nothing sacrosanct about the 1.5 degree threshold. The devastating impacts of climate change have already begun to play out at much lower levels of warming. When the world had agreed on the 1.5 degree target in the Paris Agreement, as something worth pursuing in addition to the main 2 degree goal, it was under the impression there was sufficient time on hand. After all, the temperature rise had not hit the 1 degree mark at that time. However, the planet has warmed at a much faster rate after that, and the absence of any meaningful climate action during this time has meant that the 1.5 degree target is well beyond reach now.

The writing on the wall has been evident for quite some time. However, people are still being fed the narrative that a narrow window of opportunity exists to prevent the temperature rise in excess of 1.5 degree Celsius from becoming a norm. The numbers just do not stack up.

Read | Looking at 2025, Politics: Landscape of rifts and challenges

In its most recent report, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) — the UN-affiliated body that advances scientific knowledge about climate change — said the world needed to cut its annual greenhouse gas emissions by at least 43 per cent from 2019 levels by 2030 to keep alive hopes of achieving the 1.5 degree goal. But current climate actions, which every country says is their best effort, are projected to deliver barely a 2 per cent reduction in the best-case scenario by that time. There is no way this large emission gap can be bridged in the short period remaining before the 2030 deadline.

In many ways, the COP29 climate meeting in Baku, Azerbaijan, this year was the last hope for the 1.5 degree goal. It was supposed to deliver an agreement to sharply increase the money flowing into climate actions. The assessed requirement was in the range of trillions of dollars per year. However, the developed countries, whose job it is to raise financial resources for climate action, said they could commit to no more than $300 billion a year and that too only from 2035.

Sub-optimal outcomes are not new to COP meetings but this one in Baku was particularly disappointing. Although a provision for larger sums of money would not have immediately filled up the huge emissions reduction gap, it would have done two other things. It would have demonstrated the collective capability to step up effort when faced with an emergency, and it would have provided the much-required cash for developing countries to implement adaptation projects that could save lives.

Record warming

Adaptation will be critical since developed countries have failed to deliver anything close to the required emissions cuts to keep rising temperatures in check.

Advertisement

The year 2024 has already been declared to be the warmest calendar year ever, overtaking the record set just last year. The Copernicus Climate Change Service run by the European Centre for Medium Range Weather Forecasting (ECMWF) said 2024 was expected to end with a global average temperature that would be at least 1.55 degree Celsius above pre-industrial levels.

Read | Looking at 2025, The Economy: Some positives, some concerns

The 1.5 degree Celsius threshold mentioned in the Paris Agreement does not refer to a single-year breach, but rather a long-term trend, like an average over a decade. However, it seems the world has already entered a period with temperatures consistently higher than this threshold.

June 2023 was the first time when the monthly global average temperature crossed the 1.5 degree mark, and it has remained like that ever since, barring the month of July this year. In fact, ECMWF data show that the 12-month period between November 2023 and October 2024 was about 1.62 degree Celsius warmer.

The year 2023 was also the first time when each and every day exceeded 1 degree Celsius warming over corresponding periods in pre-industrial times. A total of 173 days in 2023 breached the 1.5 degree mark, while two days, in November, went above 2 degree Celsius for the first time ever. Similar figures for 2024 are still to be released.

Advertisement

This record-breaking spell of very high temperatures has resulted in unprecedented heatwaves and several other extreme events throughout the world, killing thousands of people. They also have led to significant impacts on human health, natural environments and infrastructure.

Tepid response

The response has been far from commensurate. And it is only likely to weaken further, with US President-elect Donald Trump widely expected to walk out of the Paris Agreement once again, just as he had done during his previous term. The fear is that this time a few other countries might follow suit. Argentina triggered this speculation at the COP29 meeting when it abruptly pulled out its negotiators mid-way through the conference. While it has ruled out any such plan for the time being, there is a growing frustration amongst the developing countries about the increasing ineffectiveness of the current climate regime governed by the Paris Agreement.

Developed countries have not fulfilled any of their commitments — on emission cuts, on finance, or on technology transfer — and there is nothing to be done about that.

This is one reason why a new case in the International Court of Justice (ICJ) has created so much excitement, particularly among the developing countries. The case, still being heard, seeks advisory opinion of the ICJ on the obligations of countries on climate change. The case is being seen as a possible new way to put pressure on developed nations to deliver on climate obligations.

Advertisement

A lot of blame for climate inaction would invariably be put on Trump, but the fact is that even without him, the US has not exactly been a flagbearer for enhanced climate action. In fact, it is one of the worst performers, considering that it has the highest share of historical emissions, about 25 per cent. Even its current targets — 50-52 per cent emissions reduction by 2030 on 2005 levels, and 61-66 per cent by 2035 — represent the bare minimum that is required from the world as a whole, not from the country with the largest responsibility for climate action.

The international climate regime also gives a free pass to China, the world’s largest emitter of greenhouse gases for the last almost two decades. Latest data show that China now also has the second-largest share of historical emissions, just behind the US. It has overtaken the European Union and accounts for about 12 per cent of the emissions since 1850. But as a developing country, China is not mandated to reduce its emissions, which has grown almost four times between 1990 and now.

Drastic emission cuts, the kind that the IPCC says are necessary to meet the Paris Agreement temperature goals, are unlikely to happen in the 2030 or 2035 timelines. That may throw the 1.5 degree target out of the window but does not necessarily mean the end of the world.

New technologies

Accelerated elimination of fossil fuels — the key reason behind global warming — and a shift to cleaner and renewable sources of energy in the post-2035 period is not an unrealistic possibility.

Advertisement

Technology hurdles holding up swift energy transition do not seem as insurmountable as they did just a few years ago. Efficiency limits on renewable systems, technical and economic feasibility of carbon capture or removal technologies, or challenges of battery storage systems all appear solvable within the deadline imposed by climate change, thanks to rapid advancements in disruptive technologies such as artificial intelligence and quantum systems.

Clean energy solutions happen to be one of the biggest focus areas for research in AI, quantum science and biotechnology.

Also, a country like China is likely to reduce its emissions quickly once it decides they have peaked, which can be anytime now. China has created a renewable energy capacity that is greater than the rest of the world put together, which can enable a quicker shift away from fossil fuels than any other country has so far managed. The scale of Chinese emissions reduction in the post-2030 timeframe would be most critical for achieving climate targets for 2050.

But the shift is unlikely to be painless. Climate impacts are not going to go away the moment emissions begin declining. They are expected to continue to worsen for a few decades before changing course. Developing countries, particularly the small island nations, would continue to get disproportionately impacted by extreme weather events. And there is little they can do on their own.

Advertisement

Therefore, adaptation is extremely critical in the short term, particularly for developing countries. Unfortunately, most of these countries are also resource-starved, making them dependent on foreign help, both in terms of money as well as know-how, to fulfil their adaptation requirements.

That is why an initiative such as Early Warnings for All, being executed by the World Meteorological Organization, is an important step forward. More than half the countries of the world do not have effective early warning systems even for routine events such as rainfall or cyclones. With weather events becoming increasingly erratic and ferocious, ensuring the setting up of an early warning system in every country is the minimum the world can do to minimise the damage from climate change.

Amitabh Sinha is Climate and Science Editor, The Indian Express

NEXT: Law

Search

RECENT PRESS RELEASES

Related Post