Renewables and agriculture—friends, not foes

September 25, 2024

There is enough land in Europe for wholly renewable energy without compromising nature protection or food production.

Renewable-energy projects can occasion local flashpoints and how policy-makers select their location is critical. Yet one thing is clear: Europe has ample land to expand renewables, preserve nature and grow food. A recent briefing from the European Environmental Bureau (EEB) shows that enough is available, primarily in rural areas, without impinging on agricultural terrain.

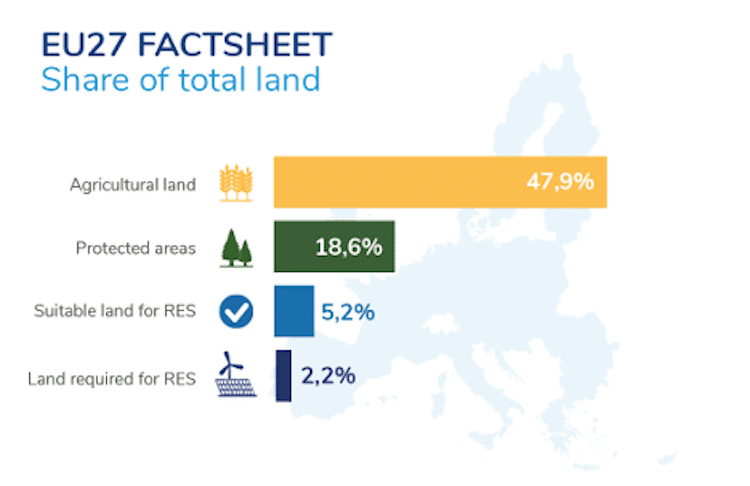

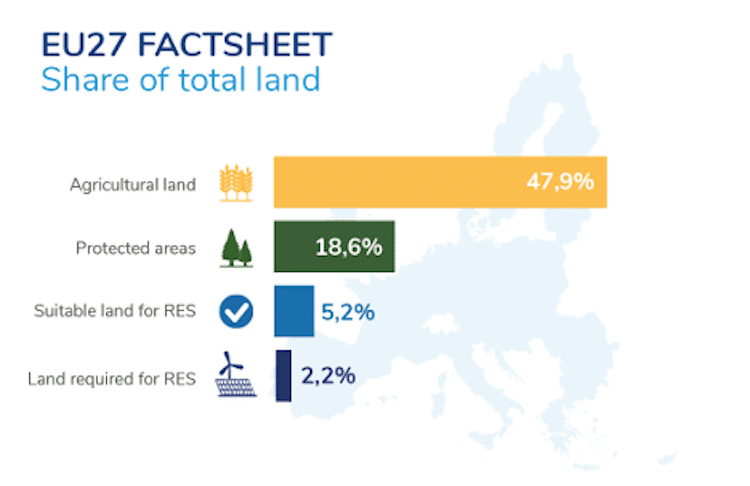

The Joint Research Centre estimates that 5.2 per cent of land in the European Union is ideally suited for accelerated renewables deployment, excluding natural protected areas and high-value agricultural lands. Yet the EEB’s latest report finds that only 2.2 per cent of the EU’s land area would be needed to accommodate sufficient renewable-energy sources (RES) to replace entirely fossil-fuel (and nuclear) generation.

Spatial mapping

Under recent EU legislation, member states must conduct spatial mapping to identify lands that have the potential for renewable energy, followed by selection of specific areas for ‘acceleration’. Projects in these Renewable Acceleration Areas (RAAs) will be authorised more quickly as they will not need such rigorous environmental-impact assessments. If done thoroughly, this has the potential to make securing permission for renewable projects much quicker, yet safer for biodiversity at the same time.

Some renewable locations are ‘low-hanging fruit’, including brownfield sites, rooftops and degraded agricultural lands. These should be given priority for new renewable developments because they are the least likely to create conflicts with local populations, nature or agricultural production.

Availability of suitable land for solar farms and proximity to transmission infrastructure are important in determining the feasibility of solar projects. Large-scale photovoltaic (PV) installations are often deployed on open areas such as fields or former industrial sites. While the latter, along with rooftops, are viable options for hosting renewables, they are insufficient to meet growing demand. The real potential lies in rural areas, which account for 81 per cent of suitable land in the EU.

Coexisting in harmony

Renewable energy does not threaten agricultural production—indeed they can coexist in harmony. Suitable rural areas often comprise degraded agricultural land, which can be repurposed for renewable energy projects. Without jeopardising farming practices or endangering biodiversity, the EU can cut carbon emissions and revitalise rural economies.

We need your help.

Keep independent publishing going and support progressive ideas. Become a Social Europe member for less than 5 Euro per month. Your help is essential—join us today and make a difference!

Yet croplands also have great potential where shade can be a benefit. A recent study by the think-tank Ember found that countries in central Europe could actually increase crop yields—particularly for fruits and berries—by up to 16 per cent with ‘agri-PV’. Additional revenues from electricity generation anyway far outweighed any losses in output. Shielding crops from more extreme weather events is a bonus, alongside the potential to reduce water consumption for crop cultivation. There is great potential across the EU to utilise this technology to allow farmers to increase yields while accruing solar-energy revenues.

Beyond land use, the spatial requirements for renewable-energy projects extend to infrastructure and grid integration. Expanding renewable-energy capacity demands upgrades to the electricity grid to accommodate solar and wind power. This benefits countries with land constraints by making it easier to import and export surplus energy across the continent and ensure a more resilient energy system.

In a renewables-based system, national energy planning is insufficient. A European super-grid would tap into different renewable hubs around the continent and balance out each country’s renewable potential and limitations. In Germany, for instance, the EEB’s report finds that the land for onshore wind RAAs is insufficient to meet expected renewable energy demand. Greater grid interconnectivity will mean energy can flow from where it is abundant to where there is greater fluctuation in production, resulting in less energy wasted and a more secure European energy supply.

Participatory processes

Engaging rural communities through participatory processes and benefit-sharing models is essential to ensure their buy-in and support for renewable-energy projects. By involving local stakeholders in decision-making and in the distribution of benefits, citizens can develop a sense of ownership of the project.

Balancing the need for renewable energy with the preservation of natural resources and landscapes is a complex but necessary task for achieving a sustainable energy future. With the aid of RAAs, advancing the roll-out of renewables will become far simpler, provided the mapping is completed accurately.

The EU has enough land for the renewables needed to decarbonise its energy system without harming protected areas or agricultural production. The responsibility now lies with member states to identify accurately which lands are suitable for acceleration. Careful national and EU-wide planning and managing of the spatial requirements for renewables can pave the way towards a greener and more resilient energy system for generations to come.

Search

RECENT PRESS RELEASES

Related Post