Shadow of the sun

October 6, 2024

Massive solar farms are eating up acreage across rural Pa. — triggering fear, anger, heated disputes

The front line in America’s struggle for a carbon-free future is a postage stamp of a southwestern Pennsylvania municipality — a place that has no traffic lights, no restaurants, no post office.

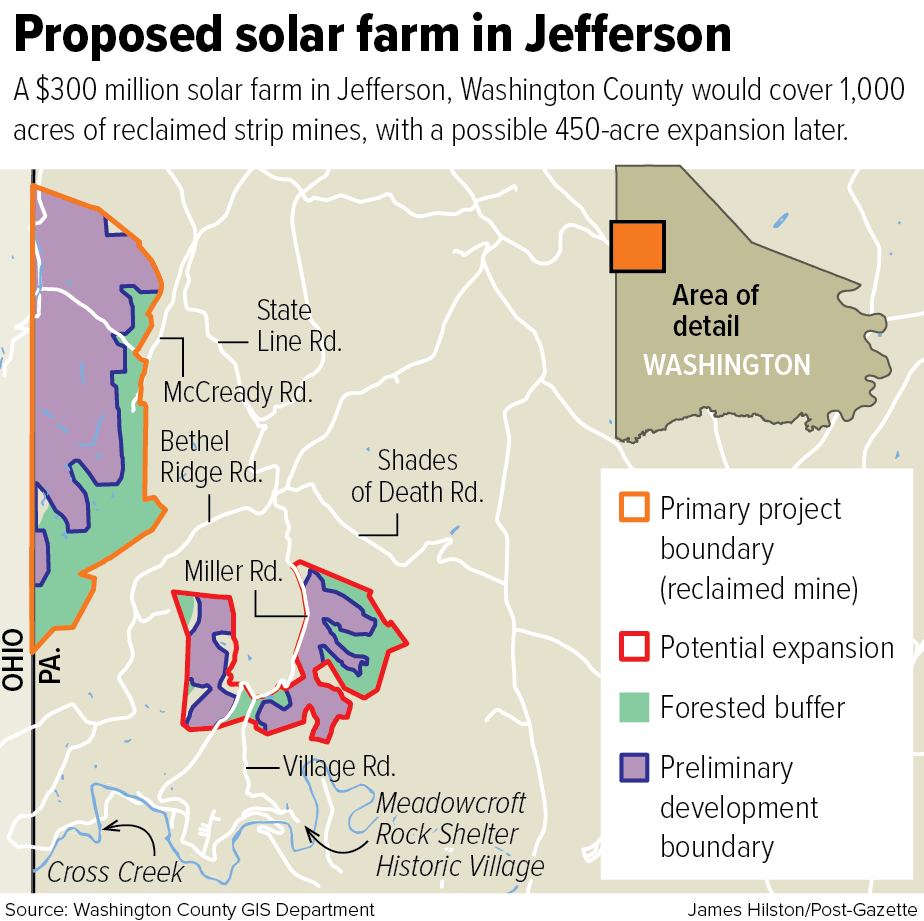

Almost no one in Washington County’s Jefferson Township, population 1,326, will say they oppose green energy. They’re just against the proposed 1,000-acre solar farm — the equivalent of 758 football fields — that developers want to build in an agricultural and wooded pocket featuring greeting card vistas of gravel roads and fields fragrant with new mown hay.

“It’s beautiful and it’s not going to be beautiful,” said Emily Waters, 34, who with her husband, 38-year-old Daniel and 7-year-old daughter Sawyer, live in a house they built three years ago in Jefferson. “It’s what we love out here. It’s slowly being stripped away from us.”

And they don’t see much benefit in return.

“Are we getting lower electricity rates? We are not,” she said. “How are the local people really benefiting from this?”

Rebecca Prebeg gets emotional while voicing her feelings about solar farms at a township supervisors meeting last month in Jefferson Township, Washington County. (Lucy Schaly/Post/Gazette)

Nearly 60% of Pennsylvania’s electricity is generated from natural gas, followed by nuclear power, 31.9%; coal, 5.4%; and other sources, 3.7%, according to Pittsburgh Works Together, a Green Tree-based economic development group. Those figures are changing fast.

Less than 1% of the electricity generated in Pennsylvania comes from the sun today, but utility-grade solar energy production is expected to explode 288% to 3,321.62 megawatts between 2023 and 2028, according to the Washington, D.C.-based nonprofit Solar Energy Industries Association. In 2023 alone, utility-scale solar capacity in Pennsylvania increased four-fold to exceed 800 megawatts, enough to light 400,000 homes.

Some residents worry the developments will hurt property values, which developers dispute.

Residents line up to speak at a supervisors meeting on solar farms last month in Jefferson Township, Washington County. (Lucy Schaly/Post/Gazette)

“I don’t have a mansion in any sense, but it’s my home,” said Brenda Coughenour, 71, who lives in a one-story, 100-year-old house with vinyl siding in Smith Township, near a proposed 118-acre solar farm. “That’s all I have. We have homes here. How can you do this? They’re preying on these small communities.”

Tensions between solar developers, municipal officials and residents have turned particularly testy in Washington County, an hour and a half southwest of Pittsburgh, minutes from the West Virginia state line.

“I got a question for you,” one woman shouted at a Jefferson planning commission meeting in September, held at the local fire hall set up with rows of metal folding chairs. “How do you sleep at night?”

“Does this help the community at all?” another woman yelled.

Planning commission chair Alan B. Gould lamented the attacks that board members have endured since the spring as rules for solar farms were being hammered out during tense public meetings.

“Some are our neighbors, some are even family members,” Mr. Gould, 88, who joined the planning commission when Lyndon Johnson was in the White House, said about the board critics. “Called a liar after all this time — it hurts.

“This has gone sideways.”

Mr. Gould said he and another planner have considered quitting the board. Other municipal officials are also feeling the heat.

On Sept. 17, after an evening of resident shouting and tearful pleas to “protect future generations,” Jefferson Township board Chair Chris Lawrence unexpectedly stood and declared, “It’s 9:05 and I resign from the Jefferson Township Board of Supervisors.”

He has since rescinded his resignation.

“I’ve been harassed, I’ve been accused of lying,” Mr. Lawrence told a standing-room-only crowd at the firehall a few weeks later. “You have no idea of the hell I’ve had.”

Jefferson Township board Chair Chris Lawrence walks out of the Sept. 17 supervisors meeting after abruptly resigning in frustration over the debate over proposed solar farm regulations. (Lucy Schaly/Post-Gazette)

Solar development pressures in rural areas are likely to intensify in the years to come as the federal government struggles to meet clean energy goals by 2050. The Department of Energy estimates that more than 10 million acres of solar development will be needed to reach that goal — 80% of which could be sited on agricultural lands, according to the American Farmland Trust, a Washington, D.C.-based nonprofit that protects farmland and ranches.

The sun offers the cleanest, most abundant and renewable energy source, with enough sunlight shining on the continental U.S. in five minutes to satisfy the country’s electricity needs for an entire month, while the cost of developing utility-scale solar energy systems has fallen 59% over the past decade, according to the Solar Energy Industries Association.

The Inflation Reduction Act, which is investing hundreds of billions of dollars in clean energy, electric vehicles and tax credits, has sparked a nearly four-fold jump in solar module manufacturing capacity since the law was enacted in 2022.

But the generational shift in energy policy is stoking longstanding suspicions among some rural Pennsylvanians that investors are exploiting country folk to keep the lights on in city office towers. That rural America is — yet again — being made the sacrificial lamb to urban areas when the disparities of rural life already include shorter lives, higher rates of joblessness and poorer access to health care services.

Search

RECENT PRESS RELEASES

Related Post