Shifting When and Where Electricity is Used Can Avoid Gigatons of Carbon Emissions

November 15, 2024

How electricity is produced and when it is used has a huge impact on how clean it is. As such, marginal emissions, which result from a power plant turning on or increasing its production to meet increased demand, represent substantial potential carbon reductions. A newly expanded dataset from the tech solution nonprofit WattTime suggests as much as 9 gigatons could be avoided per year.

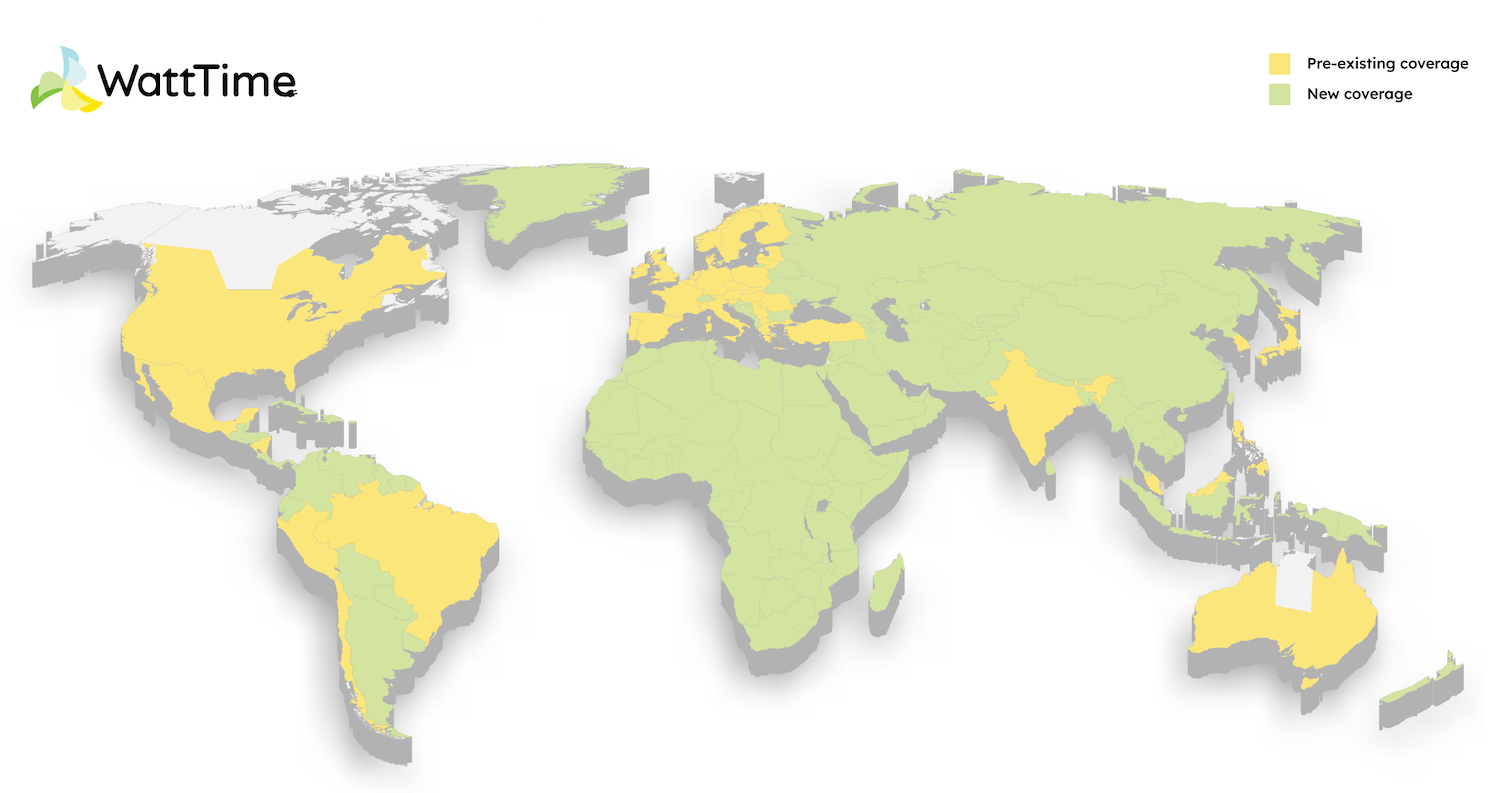

The nonprofit works with major corporations like Microsoft, Toyota and Salesforce to shift when electricity is used and where it is purchased while optimizing grid decarbonization. Its new dataset shows the marginal emissions associated with almost 100 percent of global electricity consumption. It can be used to estimate emissions based on when and where electricity is used and emissions that will be avoided based on where renewable energy projects are located. With more of this data in one place than ever before, more corporate leaders, policymakers and consumers can make informed decisions to avoid the most emissions possible.

A simple strategy for lowering peak energy use

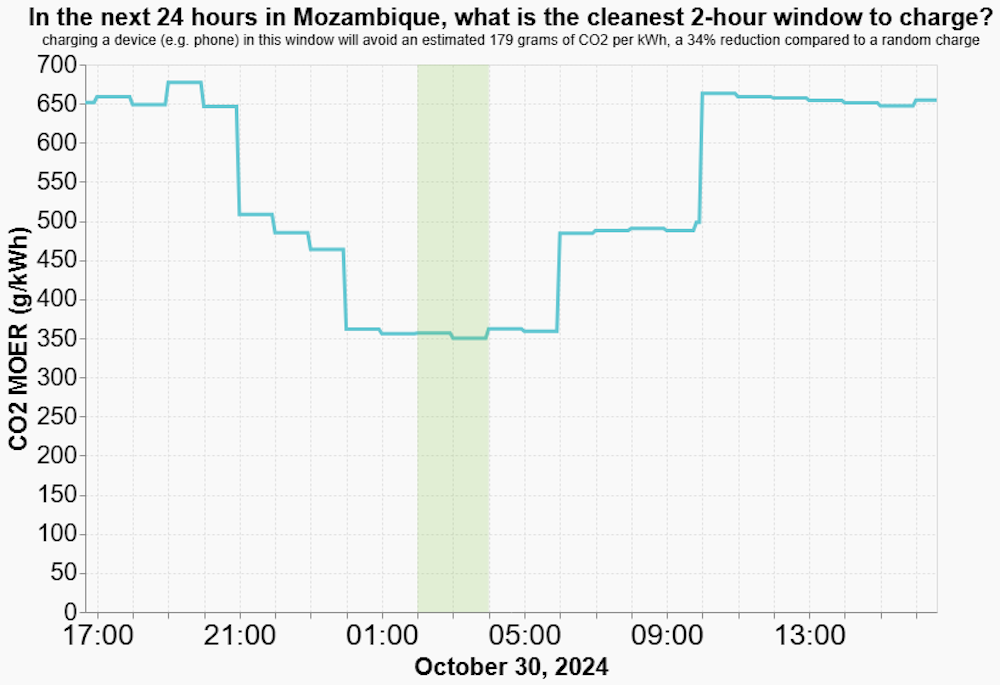

Energy is dirtier during peak times because electrical grids rely on peaker power plants to augment electricity generation when demand outstrips regular production. These plants often burn dirtier fuel, like coal, and are more polluting than baseline power plants and, especially, renewable energy sources. Marginal emissions in the United States went up over the prior ten years, which makes lowering peak energy usage integral to reducing overall carbon emissions, according to a 2022 study.

“If you, for example, have a Nest thermostat in the United States or you drive a Toyota electric vehicle or use a Windows machine, all those devices now use our data to — instead of just using electricity at any old time — look first at how clean or dirty electricity is right now and try to use it more when it will cause less harm to the environment,” Gavin McCormick, executive director and co-founder of WattTime, told TriplePundit. “That’s about 900 million devices worldwide now that are automatically using energy at cleaner times.”

But that’s not to say personal devices are programmed to charge during non-peak hours. Rather, this strategy has to do with behind-the-scenes updates and calculations in data centers. “They’re optimizing things that have no effect on the consumer,” McCormick said.

Rethinking where renewable energy is built

Unfortunately, the energy transition has been far from equitable. Not only are large parts of the globe left with minimal access to electricity, but emissions from electricity production can vary greatly by country and region. As a result, new renewable energy in areas that primarily rely on coal and other fossil fuels has a much bigger impact than it would in an area where the grid is already largely renewable.

“One of my favorite stats is a solar panel in India will replace three times more emissions than the exact same solar panel in California,” McCormick said. “So Amazon made a huge decision to build a large solar farm in India, where it will reduce a lot more emissions, instead of local on the West Coast.”

In areas like California, where renewable energy is already entrenched, adding more solar panels will just turn off existing ones because there aren’t any coal plants left to replace, he said. Under ideal conditions, California already has the infrastructure to meet most of its electricity needs with renewable energy. Adding more solar won’t eliminate the need filled by natural gas power plants after dark.

A lot of the companies that partner with WattTime are taking the same approach as Amazon, McCormick said. Another more complicated option for companies is a power purchasing agreement, which typically involves making a long-term commitment to buy renewable energy from a developer.

“A power purchasing agreement is increasingly how all these companies buy energy, so now, when you sign a contract for a power purchasing agreement, it’s increasingly common that you don’t have to sign it in your local area,” McCormick said. Instead, “You sign a contract where your two utilities will trade that information and those prices, so you’re paying to build renewable energy somewhere else, but then it kind of pays off. That’s not a carbon offset, that’s an electricity contract. It’s a really cool innovation.”

Maximum impacts versus likely impacts

WattTime’s 9 gigaton estimate of the amount of marginal emissions that could be averted each year represents the maximum possible impact. It would take 100 percent participation in optimizing energy use decisions to get there. The more likely number is 6 gigatons, but that’s still just an estimate, McCormick said.

It all depends on participation. That’s more difficult when it comes to building renewable energy in the most impactful locations, but easier for something like optimizing smart devices to use energy at cleaner times because it typically doesn’t have negative effects, McCormick said.

There are also some limitations to WattTime’s data from countries where marginal emissions aren’t tracked as precisely, but McCormick said he is confident that the estimates for those countries are accurate enough to determine which time periods in the region are cleaner or dirtier.

Decarbonization as social justice

“One thing I’m always struck by is the close connection between this marginal emissions data and social justice and environmental justice,” McCormick said. “You can drive more impact with renewable energy if there is pollution to get rid of in the first place.”

That means focusing on areas where there is less wealth and people haven’t been able to assert their rights. Doing so will result in a more equitable distribution of resources and have a much larger impact on the population’s health, McCormick said.

“What happens if you build renewable energy where we recommend?” He said. “It basically means stop building more renewable energy in the wealthiest communities in the world, where we’ve already gotten rid of pollution.”

Search

RECENT PRESS RELEASES

Related Post