The Battle Over Philly’s Clean Hydrogen Revolution

February 9, 2025

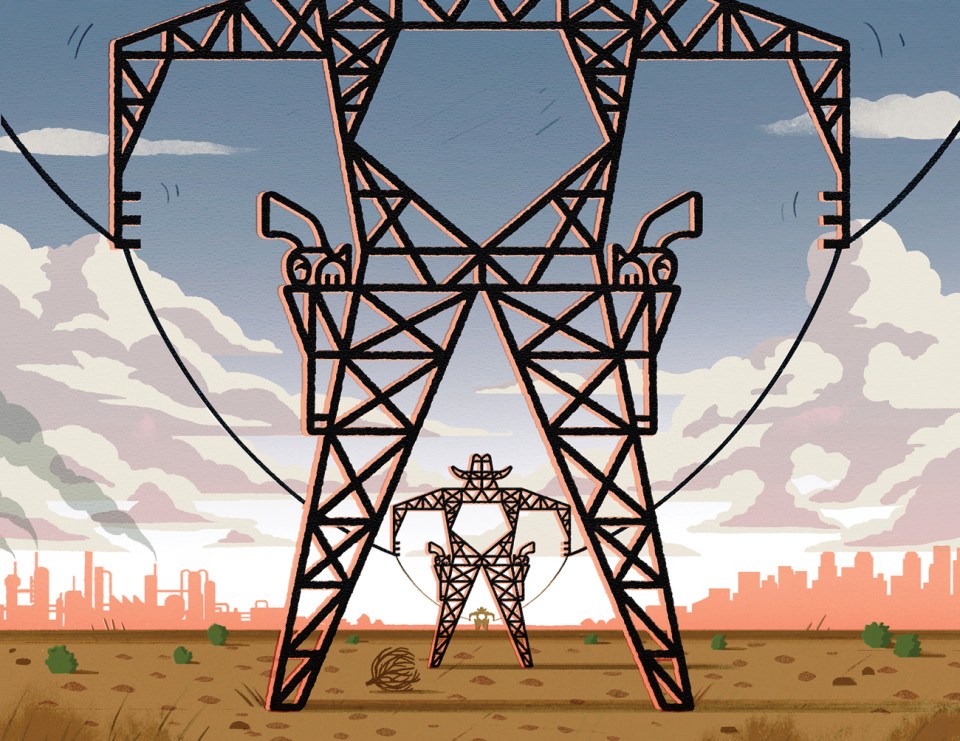

Depending on whom you ask, the MACH2 hydrogen hub could be the largest clean energy transformation the region will see this century — or an environmental disaster. And that’s if it ever even happens.

Illustration by Pete Ryan

Before we meet up, Chris DiGiulio warns me there’s a chance we’ll get hassled by security. She’s bringing a camera — which she says can record “what the eye cannot see” — that often attracts unwanted attention. When she hauls it out of the back of her Subaru, I consider the possibility that she’s messing with me. It looks like an old Panasonic camcorder: black, clunky, the kind of thing that would have produced hundreds of clips for America’s Funniest Home Videos. The idea that this machine has any elevated powers of perception seems laughable, like someone telling you they’ve found a device that can speak to the dead and then producing a Discman. When she turns it on, though, I see what she’s talking about — the scene before us appears on the screen in grainy vivid colors: invisible pollutants, illuminated by the camera, drifting away from a smokestack.

DiGiulio is an environmental chemist for the Pennsylvania chapter of Physicians for Social Responsibility, a nonprofit founded in 1961 by a group of doctors who sought to raise awareness about the public health threat posed by nuclear weapons; the mission has since expanded to environmental threats in general. The camera she’s showing me is a FLIR optical gas imaging camera, which can detect hydrocarbons and other pollutants that are invisible to the naked eye. I meet DiGiulio in Fernhill Park, at the edge of Germantown, and we walk up Roberts Avenue until we reach a spot where we can get a clear view of SEPTA’s Nicetown gas-generating power plant. DiGiulio looked up the specifications of the plant online months ago and found that it was capable of operating on a blend of natural gas and hydrogen. The plant has faced local opposition for years — DiGiulio aided Nicetown residents in their campaign against it — but it’s the hydrogen that’s currently setting her on edge. “Why would they [set it up that way] if they weren’t planning anything?” she asks.

We’re standing out here in the weeds because in October 2023, the Biden administration announced plans to build seven hydrogen hubs across the country, a $7 billion initiative to bring clean energy to shipping, trucking, ammonia production, and other industries that have been notoriously hard to decarbonize. The basic idea is that water can provide the fuel of the future — split H2O using electricity, isolate the hydrogen, compress it, and voilà: You’ve got usable energy. What officials are calling the Mid-Atlantic Clean Hydrogen Hub (MACH2) will actually comprise a network of pipelines, storage centers, supplementary green energy, and hydrogen production facilities expected to stretch from South Jersey to Delaware. The project is slated to receive $750 million in funding from the Department of Energy and could be the largest single clean-energy project the region will ever see. MACH2 is meant to be a green hub, with 82 percent of production powered by electricity generated by solar and wind, 15 percent pulled from nuclear power, and three percent coming from biogas.

That the hubs have produced mixed reactions isn’t surprising. As early as the industrial revolution, when towns and cities moved from burning wood to coal, community buy-in has required a complicated dance between energy producers and their customers. Informing residents of the potential benefits is never enough — government and industry have to offer incentives strong enough to make the new product omnipresent. But hydrogen is unique in that its production requires wasting clean energy (up to about 45 percent of power can be lost in the process of creating and storing hydrogen) to produce a different kind of clean energy. Boosters argue that it’s essential to meeting the country’s emissions targets, but many experts are skeptical about its long-term efficacy as a widespread fuel outside of a couple of industries, and environmental groups are alarmed by what they see as an opaque and potentially dangerous new industry.

If all of this sounds confusing to you, you’re not alone. These hubs are “giant collectives of projects,” says Danny Cullenward, a climate economist and senior fellow at the University of Pennsylvania’s Kleinman Center for Energy Policy. “There’s worlds of complexity within each of them.” The actual MACH2 team is quite small — it’s a nonprofit that acts as the fiscal agent and organizing body for the broad array of interested parties that make up the hub itself. Partners include the University of Pennsylvania, the University of Delaware’s Center for Clean Hydrogen, DuPont, the AFL-CIO, and many others; Cheyney University, Delaware State University, and several community colleges have signed on to do job training and workforce development. The Philadelphia Eagles have installed a solar-powered hydrogen fueling station outside their stadium, and SEPTA is developing a fleet of hydrogen buses.

According to the proposal, MACH2 is planned to begin production by drawing energy from the Salem nuclear power plant and from new offshore wind power and solar power. Philadelphia Gas Works is looking into building a solar facility at its Passyunk Plant in Grays Ferry, and a few other small solar facilities are planned around the Delaware Valley. Holtec International is developing a network of small modular reactors that produce about a third of the energy of a full-size nuclear plant to power the hub. (Where those will be placed is unclear at this point, as is how they’ll get buy-in from community members on placing bite-size reactors around town.) More pressingly, we’re talking about technology that doesn’t really exist at scale yet — at the Green Hydrogen Summit in November, MACH2 chief operating officer Manny Citron told me they were already rethinking the modular reactors because of how difficult it will be to obtain permits. How much that will curtail MACH2’s ability to generate power is unclear.

Although they were announced with great fanfare, the hubs have been spinning their wheels for more than a year now. In early January, the Treasury Department announced its final rules for a tax credit that determines the parameters hubs must meet in order to receive lucrative incentives. By many accounts, the rules are a decent compromise between industry and environmental concerns. But the announcement’s long delay hasn’t done much to abate activists’ suspicions, and speculation about how hydrogen will actually be used and produced runs rampant. In 2023, Biden enacted the Justice40 Initiative (by executive order) in an effort to alleviate the burden of climate change on disadvantaged communities. Theoretically, 40 percent of the “overall benefits” of federal programs like the hydrogen hubs should benefit communities that are overburdened by pollution. But across the country, environmental justice organizations are concerned they may be shut out of the negotiations before the hubs even get off the ground.

Hence my meeting with DiGiulio. Like many of the environmental activists opposed to the hubs, her concerns are wide-ranging — how hydrogen will be produced, how it will be used, and what the health effects will be on neighboring communities. Although hydrogen produces no emissions, it is an indirect greenhouse gas, extending the life of methane and contributing to increased ozone; a 2022 study claims that its “warming impact is both widely overlooked and underestimated.”

•

Where exactly MACH2’s infrastructure will end up could still change, but some residents of Chester — a city that’s been used as a dumping ground for heavy industry for so long that it’s often cited as a textbook case of environmental racism — are worried they’ll end up bearing the brunt of the hub’s burden when plans are finalized. Thus far, storage, pipelines, and a production facility owned by industrial gas giant Messer are planned for the city.

For years, an enormous neon sign greeted travelers with the city’s motto — “What Chester makes makes Chester” — but it was taken down in the early ’70s after it fell into disrepair, literally and spiritually. Not long after, in 1978, a fire that could be politely described as apocalyptic erupted out of an illegal trash heap under the Commodore Barry Bridge. When regulators from what was then the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Resources had discovered the dump the year prior, they’d walked through mud — stained bright white, red, and yellow — to serve the owner, Melvin Wade, a warrant. Barrels full of sodium copper cyanide, benzene, hexane, and other carcinogenic chemicals spilled out over the riverbank. On their way back to their cars, regulators’ shoes started smoking. By the time they got home, the fumes had eaten holes through their jeans. The Wade Dump seemed supernatural in its toxicity, and the fire confirmed the threat. It burned for hours, spreading smoke and particulate matter across the city. Of the firefighters who responded, almost all were later plagued by strange and sudden health problems — cancer, kidney disease, even Lou Gehrig’s disease.

Ultimately, the dump fire, along with the Love Canal spill, became the impetus for the Environmental Protection Agency’s creation of a national Superfund program. But that’s small comfort in Chester, where the remains of the Wade Dump stand as a terrifying symbol of the city’s decline. Over the course of the 20th century, the city has gone from being one of the country’s busiest sites of shipbuilding and industrial manufacturing to the Northeast’s premier junkyard. The population has been roughly halved since 1950 and is now nearly 75 percent Black. Today, more than a third of residents live in poverty and the city is host to 11 hazardous industries, although it’s best known for the Reworld (formerly Covanta) incinerator, which burns roughly 3,500 tons of trash from New York City, New Jersey, Maryland, and Philadelphia daily. It’s one of the largest incinerators in the nation, and the surrounding area’s rates of childhood asthma reflect that — four times higher than the national average. In 2022, the city filed for bankruptcy, and officials are still trying to claw their way to solvency, arguably at the public’s expense: In September, the receiver tasked with overseeing the city’s bankruptcy case announced plans to privatize the water system in order to recover money for pension funds.

Although many Chester residents I spoke to were concerned about the potential sale, they were overwhelmingly relieved at the presence of the receiver, whom they saw as a relief from endemic city corruption. Truly turning the city around will take a miracle, though, and despite MACH2’s promise of green jobs, most residents hadn’t heard of the hydrogen hubs — and those who had were skeptical of the idea that they would provide any real benefit to city residents.

“I’m looking at this just saying ‘Is this going to be a fucking money grab?’” says Zulene Mayfield of Chester Residents Concerned for Quality Living, an organization she founded in 1992 to campaign against Chester’s most famous resident — the Covanta incinerator — after it was built next to her house. “People are going to come in with a lot of promises … but [industry] has never been to our benefit.”

•

Although it’s the focus of a lot of hype right now, hydrogen isn’t a new technology. Scientists figured out how to split the water molecule using an electric current more than 200 years ago, and George W. Bush attempted to launch a major hydrogen initiative all the way back in 2003. But there’s a snag in this theoretically eco-friendly industry. The United States currently produces about 10 million metric tons of hydrogen a year, which is used primarily in petroleum refining and ammonia production. Roughly 95 percent of that is gray hydrogen, meaning it’s made using natural gas. (The color system is used within the energy industry to differentiate the types of hydrogen and is based on the type of production used to create it.) Blue hydrogen is a slight improvement — made with natural gas, but with carbon capture to lower emissions. Pink hydrogen comes from nuclear power, orange hydrogen is made using biogas, and green hydrogen is powered with renewable energy like wind or solar.

A truly green hydrogen industry has never taken off because it was considered prohibitively costly before the August 2022 passage of the Inflation Reduction Act, a section of which provided a lucrative tax credit incentivizing green hydrogen. Up to about 45 percent of energy is lost in the process of splitting the water molecule to create hydrogen, then compressing it for storage, so it’s not a particularly efficient use of clean energy — Hakai Magazine, a science and environment publication, recently called it “electrification with extra steps.” Those steps may be necessary for something like ammonia production, which requires hydrogen and serves as the base of America’s fertilizer industry, but as battery technology improves, experts are dubious about hydrogen’s ability to remain competitive when the federal tax credit runs out a decade from now.

Producing clean hydrogen isn’t simply a matter of hooking the hubs up to the grid either. The National Resources Defense Council has stressed that in order to qualify as “green,” hydrogen hubs would need to be built alongside new renewable energy sources, rather than simply diverting clean energy from the grid as it exists today — mainly powered by fossil fuels. They would also need to prove they’re able to consistently produce clean hydrogen, rather than dipping into fossil fuels when renewable energy sources go dark (a cloudy day on the solar farm, for example). Finally, the hubs would need customers close by to ensure that delivering hydrogen doesn’t result in emissions. It’s a tall order, and activists are suspicious that the hubs’ cozy relationship with oil and gas may ultimately result in a loosening of standards.

How much progress hydrogen will be able to make under the second Trump administration is anyone’s guess. Trump has threatened to repeal the Inflation Reduction Act altogether and has made somewhat incoherent comments about the dangers of hydrogen cars, comparing them to an atom bomb. “When it blows up … your wife cannot identify you,” he said at a September rally in Erie. “Let me put it that way. ‘Is this your husband?’ As they show you blood.”

But despite Trump’s fear-mongering, the fate of the hubs will likely just come down to money. The number of oil executives interested in the hydrogen hubs works in their favor, although without a wind and solar build-out to accompany the construction of the hubs, real green hydrogen may be dead in the water. Even if it does stand a chance, it’s unlikely to play all that well with environmentalists — MACH2 partners are in conversation with steel and cement makers, but the key hydrogen users (known as “offtakers”) will initially be the area’s refineries. Investing $750 million to waste green energy making slightly cleaner dirty energy isn’t exactly the bold climate action the hubs are advertising. On top of that, the hubs just won’t produce that much hydrogen. All seven hubs combined are expected to lower the country’s CO2 emissions by less than half a percent — though the DOE is hoping they’ll kick-start a national network that will entirely redefine fuel.

•

So is this just a plan so full of half measures it’s kneecapped itself before it’s even begun? Or is this the beginning of an energy boom?

Those were the main questions on everyone’s mind in November, when the Green Hydrogen Summit came to the Philadelphia Marriott Downtown, in Market East, bringing together industry leaders and other interested parties from up and down the East Coast. Outside, protesters dressed as witches, complete with green face paint (the movie Wicked was about to hit theaters), chanted “Don’t believe the hydrogen hype!” and held signs reading “Green hydrogen is wicked!” They were largely representing the Delaware Riverkeeper Network, Food and Water Watch, Extinction Rebellion, and Chester Residents Concerned for Quality Living — I’d spoken to many of them back in July, when MACH2 officials held a networking meetup at SEPTA headquarters, centered around the transit agency’s hydrogen bus pilot project. Back in the summer, their ire had been more acutely focused on hydrogen’s safety issues. Outside, protesters had strung up a banner reading “NO MACH2” above a full-color picture of the Hindenburg in flames. “[Hydrogen is] crazy explosive,” said Eric Moss of Extinction Rebellion. Moss also had his doubts about the location of the hub. He pointed out that it was well situated to power production with fracked gas and that without a significant build-out of new solar and wind projects, it would divert existing green energy from the electrical grid.

The safety concerns are real; a colorless, odorless gas, hydrogen is quite flammable and it burns invisibly — you can be fairly close to a hydrogen fire without even realizing it. MACH2 is already beginning safety training at Chesapeake Utilities’ Safety Town, an immersive miniature town built in 2020 to train hydrogen workers on emergency response protocol, tank safety, and utility line excavation, among other things. The Center for Hydrogen Safety, a New York-based nonprofit run by the American Institute of Chemical Engineers, points out that miles of hydrogen pipelines have been operating safely for years, and says it’s fundamentally no more dangerous than natural gas. It’s not hard to see why the protesters are using safety as a talking point, though: “Hydrogen may be a false solution” is much harder to explain.

It did seem that protesters had accurately clocked the industry’s distress, though — the mood inside the Green Hydrogen Summit was somewhat baffling. “I think all of us just want to be here and just all agree that no one’s got a better crystal ball than the other,” said John Sletta of Air Water America, a Bedminster, New Jersey-based company that produces industrial gases. “You got projects and stuff, but it’s like — okay, is everybody canceling everything or are we going to be okay? No one has the answer.” I spoke to him outside the conference panels, interrupting his conversation with Matt Russell of hydrogen company Plug Power, whose outlook was somewhat more optimistic. Although the focus might return to natural gas under a Trump administration, Russell pointed out that there’s a lot of money flowing to red states through the hydrogen hubs. Those senators, he said, might have the ear of the administration. “If you want to trim it, let’s talk about trim,” he said. “Don’t slam the door on it.”

Panels focused on regional issues facing the hubs, military uses for hydrogen, how to build partnerships with more potential offtakers, and the problems of transporting hydrogen. The cost of expanding the hydrogen pipeline network would be enormous, and, just as DiGiulio feared, the Department of Energy has suggested blending hydrogen and natural gas — but even conference attendees had their doubts about the efficacy of blended hydrogen.

“There’s a big discrepancy between the funding that has been appropriated by Congress and the reality of how much money it’s going to take to make the clean hydrogen strategy and road map reality. Orders of magnitude difference,” said Jesse Toepfer, a senior project manager at engineering firm Stantec. “I think either we are sitting on the ground floor of one of the biggest endeavors in the history of mankind or this is just a very pretty idea to think about.”

•

In 1986, German sociologist Ulrich Beck published a book called Risk Society. Modernity, as Beck saw it, had given rise to a social order in which dangers like the threat of starvation had been mitigated in the first world. In exchange, developed nations had taken on vague, indistinct “risks” — chemicals that cause cancer and genetic defects; radiation that can reshape DNA. Many years ago, Beck noted, it was said that sailors who fell overboard into the Thames died not by drowning, but rather by choking to death on the poisonous fumes emanating from the river. Similarly, the Delaware River, which runs alongside Philadelphia and the city of Chester, was once so noxious that pilots could smell it from the air. “Hazards in those days,” Beck wrote, “assaulted the nose or the eyes and were thus perceptible to the senses, while the risks of civilization today typically escape perception and are localized in the sphere of physical and chemical formulas.”

In the face of multifaceted, invisible risks, the media take on an outsized importance. A specialist’s knowledge is needed to explain the long-term effects of chemicals — thus, Beck argued, there is an infantilizing aspect to a risk society, in which laymen cannot fully understand the danger they may be encountering on a daily basis. Even when the risks are publicly explicated, they are difficult to grasp and difficult to believe — especially when they’re presented as a choice between “risk” and a well-paying job. “By contrast to the tangible clarity of wealth, risks have something unreal about them,” Beck wrote.

The Delaware Valley was chosen for the MACH2 site specifically because of its history of petrochemical and nuclear production. Four of the area’s seven refineries are now shuttered, and their attendant pipelines and storage facilities crisscross the region, most of them now unused. Hundreds of feet below the Marcus Hook Industrial Complex sit five massive storage caverns, carved into granite during the Cold War to protect critical supplies from a nuclear attack, and another cavern sits below ground right across the Delaware in Gibbstown, New Jersey. All of this infrastructure could theoretically be repurposed for hydrogen, although the gas has a corrosive effect on metal, so tanks and pipelines would need to be resleeved with a hydrogen-safe polymer. While all of this makes the area attractive to industry executives, Chester residents are pretty burned out. It’s possible that as MACH2 receives the Phase 1 funding it needs to really kick off community conversations they’ll be better able to differentiate themselves from the industry of the past, but the fact that everyone’s knee-jerk reaction was opposition does not bode well.

There have been some attempts to revive Chester — the Philadelphia Union built its stadium on the waterfront, and Harrah’s opened a casino nearby — but longtime residents say those businesses haven’t done much for existing residents. “We become the people who clean up, the people who do the security,” says Thom Nixon, a lifelong Chester resident who works at West Chester University. “But [we don’t get] the professional jobs where the money is being made.” In Chester, Beck’s risk society runs up against its inevitable end point. The choice presented to residents is no longer between health and jobs. The jobs never come; their health always worsens. One could paint a utopian picture of the post-hydrogen hub future, one in which solar panels cover industrial plants and buses and trucks begin to run on clean fuel — thereby reducing local asthma rates. It’s entirely possible the hub will usher that future in, but given that most of the hydrogen produced will be offloaded on refineries, residents are right to be skeptical.

“We got the prison. Why did we get the prison? Because of money,” says Joan Gunn Broadfield, a Quaker who lives in Chester and is an active member of the Chester Friends Meeting. “We got it because of promised jobs, which were a total lie. That casino supposedly was going to provide jobs [too]. Over and over again, Chester gets screwed.”

Published as “Power Struggle” in the February 2025 issue of Philadelphia magazine.

Search

RECENT PRESS RELEASES

Related Post