US sovereign wealth fund: A feasible idea to invest strategically, or a giant opportunity for waste?

February 8, 2025

Could the United States soon be joining the likes of Norway, Kuwait and Mongolia in having a national reserve to invest on projects of strategic interest? If President Donald Trump gets his way, then perhaps so.

On Feb. 3, 2025, Trump issued an executive order calling for the creation of a U.S. sovereign wealth fund.

This was not entirely unexpected. After all, the idea had been floated in September 2024 not only by the Trump team, but also by President Joe Biden’s Treasury Department.

Many at the time, including myself, deemed it far-fetched at best. But with the initiative now gaining traction, the time is certainly ripe to imagine what a U.S. sovereign wealth fund might look like.

What is a sovereign wealth fund?

In their most basic form, sovereign wealth funds are pools of government savings, usually accumulated over many years through the sale of commodities, traded goods, government-owned companies and land-use rights, among other sources.

They share a variety of objectives, such as stabilizing government finances, ensuring the funding of retirement or education programs, saving for future generations or even managing state-owned corporations.

They generally diversify investment across assets, geographies and sectors, including some, such as sports and entertainment in the case of Saudi Arabia, that are aligned with national development goals.

Sovereign wealth funds are usually associated with great wealth – Norway’s “oil fund” is estimated to be worth US$1.7 trillion. With regard to scale, Norway is hardly alone. And Norway’s fund is typical in another respect: sovereign wealth funds are often based in smaller countries with outsized natural resources, like Kuwait, the United Arab Emirates and Qatar, or even tiny Guyana in the Caribbean.

In reality, most sovereign wealth funds are more modest in size relative to their gross domestic products.

How long have SWFs been around?

Sovereign wealth funds are hardly new. The so-called modern era of sovereign wealth funds dates to the early 1950s with the creation of the Kuwait Investment Board.

But some government investment funds, such as the Texas Permanent School Fund, established in 1854, long predate the Kuwait Investment Board.

As is evident in the case of Texas, there are many such funds already operating in the U.S., including those in Alaska, New Mexico and Wyoming – all of which identify as “sovereign wealth funds.” These, of course, are state funds, but the term “sovereign” is generously applied.

Sovereign wealth funds often invest outside of their geographies, not only to diversify returns but to avoid stimulating higher inflation that may result from investing at home.

In fact, the U.S. has benefited from investments by other countries’ sovereign wealth funds. Developed market economies like the U.S. are attractive destinations for investment, given the relative strength of their institutions and the scale and liquidity of their financial markets.

Still, over the last decade there has been a rapid expansion in the number of sovereign wealth funds investing domestically, particularly in support of strategic national goals. Some of these include funds in Ireland, India and Indonesia.

Their investment programs target critical sectors and national “champions,” with a goal to mobilize foreign capital for co-investment in local markets.

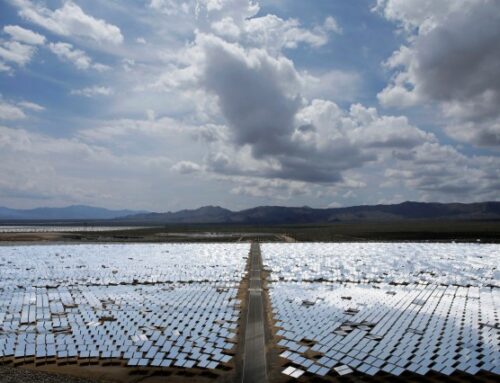

Abdullah Ahmed/Getty Images

The fundamental questions of a fund

What could a U.S. sovereign wealth fund look like? Would it be well funded? And if so, how? Through taxes, treasury bond proceeds, budget transfers, tariffs?

Would it invest globally or domestically? Could it be used to reinforce the Social Security system? Will it be used to tackle the dual deficits of budget and trade? Or will it have a strategic mandate – to enhance national security, energy security or climate security?

These are all fundamental questions that must be carefully examined; creating a sovereign wealth fund should not be a backroom exercise. It needs to be conducted openly, with expert input and public deliberation.

The process belies even more challenging organizational and governance decisions concerning the legal structure, ownership and management of the fund, the independence of its governing board, and its distance from government influence in its decisions.

After all, the history of sovereign wealth funds is not without failed attempts. Take Malaysia’s 1MDB, which was usurped for political and personal gain and became a multibillion-dollar corruption scandal, or Venezuela’s macrostabilization and development funds, which were both effectively exhausted.

In these cases – and others – the breakdown can be connected to failures in governance, both in design and culture, and ultimately traced back to politics.

Where does the US start?

It is interesting to note that it was George W. Bush’s Treasury Department during the financial crisis in 2008 that was most influential in encouraging sovereign wealth funds to define a framework of governance practices and principles.

Known as the Santiago Principles, this set of 24 precepts, agreed to in 2008, are intended to ensure transparent and sound governance with adequate operational controls, risk management and accountability.

To be successful and in line with the Santiago Principles, a U.S. sovereign wealth fund would have to be grounded in a functional governance structure that allows investment projects to be evaluated based on commercial merit.

It would also need to be free of political interference and operate openly, transparently and at arm’s length from any personal or professional interests of any related parties.

Where would it invest?

The next thing to consider is the fund’s investment objectives and strategy. Trump has suggested that such a fund could be used to buy TikTok. But would that represent a strategic investment that advances the national competitiveness of the U.S.?

Perhaps instead, a sovereign wealth fund might be better placed investing a majority of its capital in private markets and core infrastructure in the U.S. under a focused strategic mandate that directs money to key national priorities.

Essential here is for the fund to be “additional.” That is to say it would invest in projects that other investors would not be able to finance on their own due to scale, difficulty or duration. In essence, the fund would “crowd in” investors, rather than crowding them out.

And what about funding?

Perhaps the most critical question still remains: Where will the money come from?

Increased taxes are a nonstarter due to political will and, of course, Trump’s campaign commitments.

Treasury bond issuances would only increase U.S. debtedness and likely lead to higher inflation. Allocations from the government’s own budget also seem to be a non-starter, as U.S. budget deficits have long been well-entrenched.

The president has suggested that a fund could use tariff payments – but the reality of the tariff rollout is itself questionable and apparently open to negotiation.

Ore Huiying/Getty Images

A more practical option may be a take on the traditional private equity limited partnership. In this model, the U.S. serves as general partner and joins other institutional investors – including other sovereign wealth funds – to invest in the fund.

As general partner, the U.S. would appoint a management team that would select and manage the investments – for a fee, of course. Its mandate would be to target strong market returns, while advancing the strategic national interests of the U.S.

The National Investment and Infrastructure Fund in India is one such example. This approach would require a smaller initial capital commitment from the U.S. and give the manager discretion over where and how to deploy capital. Needless to say, the call for strong foundational governance is reinforced under such a plan.

To be clear: The challenges, constraints and risks of launching a U.S. sovereign wealth fund are orders of magnitude greater than similar endeavors in Guyana or Suriname.

Imagining the creation of a fund is certainly feasible. But ensuring the fund will genuinely enhance the intergenerational welfare of all Americans may still be far-fetched.

Search

RECENT PRESS RELEASES

Related Post