December 30, 2022

The War on Drugs Part II’: California taxes, rules are killing small legal weed farms

KEVIN RECTOR BRIAN VAN DER BRUG

When Johnny Casali was a teenager growing weed illegally in the mountains of Northern California, there was always the risk the government would ruin everything — that his plants would be discovered and ripped up, or that he would be discovered and locked up. In the 1990s, dozens of federal agents raided his family’s Humboldt County farm, and Casali spent eight years in federal prison.

Today, weed is legal in the state and Casali grows it openly on his family farm. Law enforcement helicopters don’t fly over as often, and there’s not much risk of another raid.

Still, the government threatens his livelihood, Casali said.

In place of handcuffs and prison sentences to deter cannabis cultivation, the state has established a vast system of taxes, fees and regulations to control it. The taxes are steeper and the rules more onerous than those in other agricultural sectors. Casali and other small California cannabis farmers say they are increasingly impossible to comply with given the glut of weed on the market and the plummeting price per pound of wholesale pot.

“Are all the small farmers destined to fail? That’s our biggest fear,” Casali said one recent morning at his farm. “It’s the War on Drugs Part II.”

Across California’s legal cannabis industry, small operators are facing financial ruin. Farmers have been forced to rely on government assistance and have stopped paying their taxes. Some legacy growers who entered the legal market are considering going underground into the thriving illegal market, where they would avoid state oversight and tax bills.

The farmers say they support regulations that ensure their weed is safe for consumers. But they object to rules that nitpick their farming practices and needlessly drive up their costs — rules that their illegal competitors don’t follow. In addition to paying cultivation and excise taxes, state licensing fees and other upfront costs, legal cannabis farmers have been forced to comply with intense tracking and testing regimens and an array of bureaucratic rules that dictate how they can farm their crop — some of which state officials have conceded are excessive and have begun to walk back. One that the state eliminated had required farmers to weigh every one of their plants individually. Another restricted outdoor farmers’ use of “light deprivation,” a traditional farming method to limit the amount of sunlight plants get in the field.

Licensed cannabis farmers in California face heavy restrictions on how they sell and market their products. They generally can’t sell directly to consumers, and legal cannabis can’t be sold after 10 p.m. or to those younger than 21. It can’t be sold in stores to anyone at any time in more than half the states where localities have barred retail sales. Because cannabis remains illegal federally, it also can’t be sold across state lines, meaning the flooded California market is the only one where legal farmers in the state can currently operate.

Faced with increasingly desperate pleas from licensed farmers, California has eased regulations and state and local taxes have been reduced in recent months, after officials began realizing that legal weed can’t be the cash cow they once envisioned. Not if they expect it to also compete with and one day overtake the illegal weed industry, which is causing labor and environmental catastrophes across the state. State officials also opened the door recently to potential cannabis sales in other states under interstate trade agreements.

Still, many small farmers say California’s legal cannabis system remains wildly out of touch with economic realities and must change further if they are to survive.“Those of us who really put our best foot forward, who came out of the darkness and into the light,” Casali said, “are now being punished.”

One farm’s finances

When Casali got out of prison and returned to the small Humboldt farming community he’d grown up in, he received two gifts from old friends who were happy to have him back.

One was an envelope containing $20,000 in cash, to get him back on his feet, he said. The other was a weed plant containing the rare genetics of his mother Marlene’s favorite strain, “Paradise Punch” — which his friend had saved for Casali after his mother died while he was in prison, and which helped set him up for the future.

Casali took his mother’s plant and crossbred it with another to create “Whitethorn Rose,” a proprietary strain that quickly gained attention and helped put Casali’s Huckleberry Hill Farms on the map with consumers. It helped him pivot harder toward the craft cannabis market, which many experts now see as the only path forward for small farmers.

When California’s cannabis laws were being designed, policymakers capped the acreage any one licensed operation could cultivate in order to help small, legacy cannabis farmers compete with newcomers who had venture capital to build out massive farms. The rule was to sunset after five years. However, a regulatory loophole added by state agriculture bureaucrats allowed those huge new farms to form anyway by purchasing multiple licenses, and they quickly began pumping out product by the truckload — saturating the market and driving down the price per pound in the process.

Casali’s success with “Whitethorn Rose” has helped him survive the deluge, allowing him to fetch higher prices than some other local farmers and get at least some of his product into stores, which isn’t easy now with the glut. Still, Casali’s fortunes have floundered in recent years, just like those of his neighbors. Casali said he and his partner, Rose Moberly, working seven days a week for eight months straight, produced 600 pounds of weed last year. That would have put them in the black in the past, when weed sold for more than $1,500 a pound.

But Casali struggled to find buyers. When he did, they paid him a fraction of what he used to get. Some took his weed and never paid.

Casali jarred 6,500 quarter-ounces of his best weed that year. He sold 3,200 of those jars for $75,000 to retailers, but was paid only $25,000 and is still owed the rest, he said. He also sold 60 pounds of weed to Grassdoor, the California weed delivery service, for $30,000. His distributors — the legally mandatory middlemen between farmers and retailers — took 17%.

Casali couldn’t sell the rest of what he produced. He destroyed the other 3,300 jars, donated 350 pounds to Dear Cannabis, an organization that gives free weed to medical cannabis patients in need, and chipped 55 pounds into compost. Meanwhile, Casali incurred more than $200,000 in costs that year.

Many were operational, such as $30,000 for crop inputs such as fertilizer and other soil amendments, another $30,000 for “trimming” or harvesting his delicate weed by hand and thousands more on standard business expenses such as banking, insurance and property taxes.

California’s legalization of recreational cannabis in 2016 ushered in a multibillion-dollar industry estimated to be the largest legal weed market in the world. But many of the promises of legalization have proved elusive. In a series of occasional stories, we’ll explore the fallout of legal pot in California.

Many others, however, were the result of special cannabis taxes and regulations, such as $11,800 in state licensing fees; $7,000 on required testing for factors like potency; $5,375 in county excise taxes; $5,000 on a nursery license; $3,000 on mandatory “track and trace” compliance costs; and $1,000 on a special transportation license to move his product to distributors.

At year’s end, Casali and Moberly reported losses of about $130,000, he said. For 2022, they eliminated as many expenses as possible, taking on more and more of the farm work themselves, Casali said. But they still expect to lose an additional $50,000.

And they are not the only farmers operating in the red.

Humboldt horror stories

One afternoon last month, dozens of local farmers and cannabis industry workers called into a Humboldt County Board of Supervisors meeting to urge a reduction of the local cannabis excise tax.

The tax, known as Measure S, was approved by county voters in 2016 to raise public funds from an industry that had thrived illegally in Humboldt’s hills for generations, charging newly legal farmers between $1 and $3 per square foot of land licensed for cannabis production. The tax has raised more than $52 million since 2017

However, many cash-strapped farmers have stopped paying and started racking up large delinquency bills, Humboldt Chief Financial Officer Tabatha Miller told the board that day.

For cultivation in 2020, the county billed farmers $19.6 million in excise taxes but had received only $11.6 million as of October. For cultivation in 2021, the delinquency rate increased, despite a previous decision by the board to cut the excise tax by 85%, Miller said.

Distraught farmers bombarded the supervisors with horror stories. They described plummeting prices for wholesale weed, not getting paid for product they’d put into the market and not being able to sell some of their weed at all. They spoke of exhausting days of field labor without the help of workers, whose labor they said they could no longer afford, and anxious nights completing compliance paperwork.

Brian Roberts, of Homestead Collective Weed Co., tallied up what he said were $24,000 in taxes and fees “prior to even planting” any crops, which he said may be “great for the county, but it’s killed the entire Humboldt County cannabis industry.”

Kevin Jodrey, of Wonderland Nursery, said the state’s cannabis rules had empowered massive companies to move in and take over the industry while small farming communities that have been cultivating cannabis for generations have been left to die.

“I’ve never seen so many stores and buildings empty in southern Humboldt, and I’ve never seen so many people make a mass exodus,” he said. “The industry’s not gonna go anywhere, it’s just going to bypass the people who created it, and I think that that’s the real crime.” Karla Knapek, of Honeydew Valley Farms, said she’d reduced her farm crew from 19 people to 10, but it is still costing her about $375 to grow a pound of weed — yet she’d been getting offers of only about $200 a pound. “We’re asking ourselves, ‘Does it even make sense to finish harvest at this point?’” she said. After the farmers spoke, the supervisors voted to suspend the county’s excise tax for the next two years, echoing a state decision earlier this year to remove its own cultivation tax.

At the back of the boardroom, farmer Craig Johnson broke into a broad smile as his wife, Melanie, seated in front of him, clutched his hand to her shoulder and fought back tears.

The Alpenglow Farms couple said they have been raising a family and fighting for their way of life in southern Humboldt County for years. The removal of the county tax would help with that, even if just by a little. “It means that we can catch our breath for a minute,” Melanie Johnson said.

Economics of over-regulation

When two inspectors from the California Department of Cannabis Control arrived at Casali’s farm last month, he and Moberly were ready.

Their records were all in order and carefully arranged in binders on a table in a separate building on the farm that also served as their “harvest storage area,” where different batches of weed were separated into locked rooms, all according to state regulations.

Laid out were Casali’s business licenses and harvest logs. There, too, were all his manifests for Metrc, the system for tracking and tracing every bit of cannabis legally produced in the state, whether it’s sold or not. Inspectors Laura Powell, with a tablet in hand, and Eric LeBlanc, holding a measuring wheel, began their tour. In one of the harvest rooms, Powell stopped at a neat stack of 12 plastic bins, each full of weed. On one, Moberly had placed a label identifying the batch that read, “1 of 12,” but the 11 other bins didn’t have labels.

“With this label, a replica ID just needs to be on all of [the bins],” Powell said, as she started logging the error into her tablet.

“I know it’s hard, because the regulations change,” she said. Casali, who had been up since 4:30 a.m. ensuring everything was in order for a perfect inspection, seemed frustrated.

“We are just so close to not being able to do all the work,” Casali said. “It’s just Rose and I. We’re really doing our best.”

In a book published this year titled, “Can Legal Weed Win? The Blunt Realities of Cannabis Economics,” UC Davis economists Robin Goldstein and Daniel Sumner outlined a number of headwinds faced by small legal cannabis farmers in places like Humboldt County. Among the largest, they found, were the array of taxes and regulations that states like California have put in place for legal growers — despite knowing it would give their illegal competitors an advantage.

“Getting legally compliant means lots of fees; unknown, and almost always longer-than-expected, waiting periods; complex testing, tracking, packaging, and labeling requirements; and steep cannabis taxes,” Goldstein and Sumner wrote. “Illegal weed businesses do not face any of these costs or taxes, so they can run leaner, lower-cost operations and sell comparable products for lower prices than legal businesses can.”

Law enforcement can go after bad actors working on the illegal side, they said, but more will always crop up in their place as long as there’s money to be made. Quality, safety and presentation of the product matter, but price is often king — and Goldstein and Sumner found prices at unlicensed weed retailers were significantly lower than at licensed retailers, in part because of all the money that legal operators have to spend on compliance.

In states like California, the price disadvantage for legal operators is compounded by additional restrictions that cede large numbers of consumers to the illegal market, including adults younger than 21, late-night buyers and those who live in localities that have banned retail cannabis shops.

Goldstein, who serves as director of the UC Davis Cannabis Economics Group, said much of the state’s failed system is the result of political maneuvering, lobbying and compromises during the effort to pass Proposition 64 — which legalized recreational weed in the state. The state should be looking to strip back some of that regulation, having seen it doesn’t work for most of the industry, including farmers, he and Sumner said. “Generally speaking, we would say go through your regulations very carefully,” Sumner said, “to decide what you could possibly reduce.” Gov. Gavin Newsom and state legislators acknowledged the system is more burdensome for cannabis growers than intended when they removed the state’s cultivation tax, and Newsom has called for legislators to eliminate additional barriers to farmers’ success, as well.

David Hafner, a spokesman for the California Department of Cannabis Control, said the state has already streamlined some regulations and issued $120 million in grants to expand cannabis retail and help small farms qualify for state licenses. He said his department heard Newsom’s call for more relief “loud and clear” and intends to “redouble” its efforts to provide it in the coming year.

“There is still more that can and should be done at all levels of government,” Hafner said.

Hustling in the hills

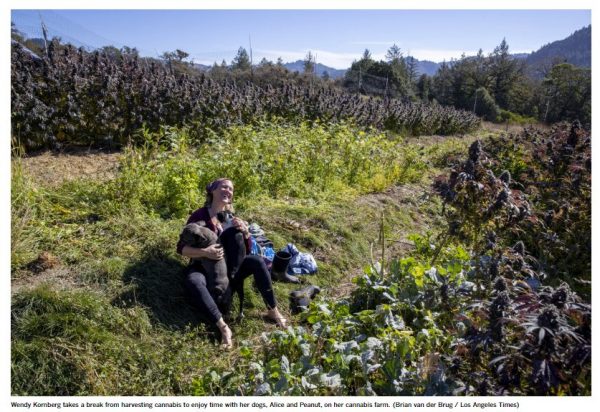

Toward the end of Humboldt County’s recent harvest season, Wendy Kornberg stood in her cannabis field outside the famed weed town of Garberville, trimming sticky buds with gloved hands while waxing philosophic into a headset about her long relationship with weed.

It was Halloween morning, and heavy rains forecast for the days ahead threatened her unharvested crop. Kornberg was participating in a virtual discussion about cannabis farming while rushing to harvest as many plants as possible so she could get home for trick-or-treating with her kids.

“Everything is fraught with uncertainty right now,” she said as she snipped away with a pair of pruning shears.

A second-generation Humboldt County weed farmer, Kornberg used to do “guerilla grows” in the woods as a teenager and later worked as a trimmer. She started getting more serious about growing weed as an occupation after California legalized medical cannabis, and now has a working legal farm, called Sunnabis, on land she rents not far from her parents’ former homestead.

She works the land with her partner James Beurer, who is from Michigan, and they live together nearby with their five kids — she has two, Beurer has three — and their four dogs, eight cats and a coop of chickens. In addition to growing and selling weed wholesale and trying to break more heavily into the craft market, Kornberg works as a consultant for out-of-state cannabis operations, teaches courses for up-and-coming farmers and helps run a program called Ganjier, which offers “cannabis sommelier” certifications to other would-be weed experts.

“If we didn’t have side projects and the teaching stuff we do, it would be very hard to maintain the farm,” Kornberg said. “It wouldn’t be operational.”

The night before, Kornberg and Beurer cooked hamburgers on a grill outside their three-story, mud-and-hay-walled drying shed. Inside, big branches of buds hung next to tags identifying their strain: “Strawberry Milk,” “Grass Valley Girl,” “Mango Kush,” “Pancakes.”

The farm, on a sloping bit of land surrounded on all sides by hills, looked beautiful as a sliver of fall moon rose above the snaking Eel River below.

Still, a sense of frustration loomed as the dinner conversation turned to the barriers that California has put in place for local cannabis farmers.

Kornberg said she was doing great until the state’s legalization replaced its largely unregulated medical cannabis model. In addition to all the new competition, Kornberg said, the state’s new rules and licensing fees around manufacturing and retailing made it too costly for her to continue selling the THC-infused topical products and tinctures she had perfected. Rules for tracking and tracing every bit of plant she produced began gobbling up her time, as did getting county permits to build a new water retention pond for watering her cannabis crop. Without buying a nursery license, she couldn’t sell her seeds.

Worst of all, Kornberg could no longer sell directly to the medical customers she had cultivated over the years, she said, and had to start going through — and paying — a distributor.

In 2020, nearby wildfires rained ash on her crop, costing her much of it. A manufacturer stiffed her after she gave him more than 136 pounds of weed, paying her nothing. A distributor gave her just $3,500 after she gave him 300 pounds of weed, despite owing her far more. A vendor this year mistakenly gave her a male plant that seeded part of her crop, making it worthless.

Under lights strung up on the drying house, Kornberg said it was all starting to get her down — but not enough to give it all up. Not yet. The crop, the land, the farming process all meant too much to her, she said. She still has high hopes for consumers becoming more educated about their weed and turning, as a result, more toward the sort of craft weed that only comes from small farmers like her.

“Quality is always going to sell and there is a place for the craft grower, 100%. I have no doubt about that,” she said. “People buy Lindt chocolate because they know it’s better than Hershey’s.”

After sleeping rough in a shed on the property that night, Kornberg and Beurer got up to harvest in the morning with the help of two friends, before heading off late that afternoon to go trick-or-treating with the kids.

A fair bit of weed was still in the field — something Kornberg said policymakers should see.

“Get out here and farm with us for like three hours,” she said, “and tell us if you still think [the state’s system] is rational.”

Search

RECENT PRESS RELEASES

Related Post

Kevin Rector

Kevin Rector