4 Pitfalls to Avoid When Seeking a Cannabis Trademark (and Tips to Avoid Them)

July 8, 2025

Building a recognizable cannabis brand is only half the battle—learning to protect it will set you apart in the market and help avoid expensive litigation. Because marijuana remains a Schedule I drug under the Controlled Substances Act (CSA), trademark protection can be difficult to navigate or flat out unavailable. Cannabis business owners currently have several avenues for protecting their brand, but success depends on avoiding the most common pitfalls.

Pitfall No. 1: Not Knowing Whether Your Mark Is Eligible for Federal Registration

The U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) examines applications for federal trademark registration. A federally registered mark—denoted by the ® symbol—provides powerful nationwide protection against infringement. But marks for cannabis products, or products merely related to cannabis, face unique hurdles under federal law.

Hemp-derived products, legalized under the 2018 Farm Bill, may qualify for registration—especially non-consumable items like topicals. However, ingestible hemp products (like CBD gummies or tinctures) have largely not yet been approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), i.e., deemed safe for consumption, so the USPTO will deny trademark applications for such goods.

Without congressional guidance or a general policy from the FDA indicating that hemp-derived products are safe for consumption, the approval process for a specific product is expensive and time-consuming. For instance, Jazz Pharmaceuticals’ (formerly GW Pharmaceuticals) EPIDIOLEX®—the only FDA-approved CBD drug to date—required roughly a decade of trials. As of 2024, the cost of submitting an FDA drug application is between $2.2 million and $4.3 million, depending on clinical data requirements.

Meanwhile, the USPTO continues to reject marks for cannabis (i.e., marijuana) and cannabis-related paraphernalia under the “lawful use” requirement. However, registration is possible for ancillary goods and services. Items historically associated with tobacco, such as rolling papers and pipes, are usually eligible, even when marketed for cannabis use.

A notable case is BBK Tobacco & Foods LLP v. Central Coast Agriculture Inc. There, BBK Tobacco (BBK), whose rolling papers have the registered mark “RAW,” sued Central Coast Agriculture (CCA) for its use of the mark “Raw Garden.” CCA brought a counterclaim against BBK, arguing that the rolling papers were, in fact, drug paraphernalia.

In support of this claim, CCA pointed to BBK’s advertisement, which included a green substance in its product. It also pointed to an interview with BBK’s founder, where he states that the products were developed for “high-end strains.” The court ruled that the RAW-branded rolling papers were not drug paraphernalia despite being marketed toward cannabis users because intent was deemed irrelevant under the tobacco exception. Unfortunately, the opinion was unpublished and therefore not binding on other courts.

Critically, therefore, advertising and branding still matter. The USPTO has rejected applications that appear to suggest unlawful use. For instance, the USPTO refused registration of “4:20” despite the applicant’s claim that it was for non-cannabis merchandise. The USPTO’s examining attorney found the name deceptively suggested a cannabis connection, providing as evidence dictionary definitions and cultural associations between 4/20 and cannabis use.

Tip No. 1: Avoid triggering unlawful-use claims. Mere disclaimers that a product is “not for cannabis use” are rarely sufficient—brand messaging, product appearance, and consumer perception all factor into USPTO review. Cannabis businesses’ best bet for federal trademark registration is to apply for a mark for truly ancillary goods and services, something that does not require or intimate the consumption of cannabis, e.g., educational services tailored to cannabis, or that can be used across the board for all sorts of other products, e.g., smoking pipes, lighters, or rolling papers.

Pitfall No. 2: Relying Solely on State or Common Law Trademark Rights

State trademark registration is often more accessible and affordable than federal registration, and most states with cannabis programs allow registration of cannabis-related marks. Such registration provides public notice of the brand within that state. However, state trademark rights are geographically limited. A trademark registered in Ohio, for example, will not prevent use of the same mark in Colorado.

Common law trademark rights—arising from use of a mark in commerce—can be signaled with a ™ symbol. Like state registrations, common law rights are limited to the geographic area of use and can be difficult to enforce, requiring businesses to prove the extent and date of use if challenged. Regrettably, they offer no protection against later-filed federal marks, even if use of the common-law trademark came first.

In Kiva Health Brands LLC v. Kiva Brands Inc., a California-based cannabis chocolate brand with state and common law rights to “Kiva” could not assert priority over a federally registered health supplement brand using the same name. Despite being the first to use the mark in California, the cannabis company’s use was considered unlawful under federal law and could not establish priority.

Trademark rights depend on the first lawful use in commerce. Lawful use in commerce can be proven through receipts of sales, pictures or screenshots of the product in stock at stores, and other business records. Note that the mark must be in actual use, and courts will not enforce a mark that was never put on the market.

Tip No. 2: Adopt a hybrid strategy—seek federal registration for federally legal products (e.g., branded smokers’ articles or apparel), and pursue state registration for cannabis goods. Keep detailed documentation of first use and geographic reach to support future enforcement or litigation.

Pitfall No. 3: Using a Mark That’s Too Similar to Someone Else’s

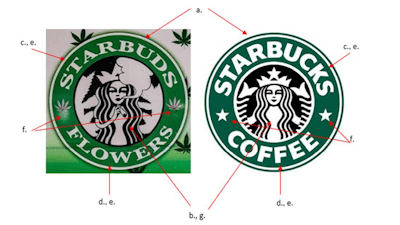

Many cannabis brands creatively mimic well-known names or logos, but this approach carries significant risk. A mark that is too similar to an existing brand may trigger a trademark infringement claim if it causes consumer confusion.

Seemingly clever branding can become an expensive liability if the brand can be confused with another. The owner of the existing mark may bring a trademark infringement claim against the cannabis business, particularly if it can show that there is a likelihood of confusion between the marks. Courts weigh several factors when determining a “likelihood of confusion,” including:

- Similarity of the marks;

- Relatedness of the products;

- Channels of trade, i.e., area and manner of concurrent use;

- Consumer sophistication, i.e., the degree of care consumers are likely to use in discerning the marks;

- Strength of the plaintiff’s mark;

- Evidence of actual confusion; and

- Defendant’s intent to “palm off” its product as that of another.

In Starbucks Corp. v. Brandpat, LLC, a federal judge granted an injunction against the cannabis company using the brand “Starbuds,” citing a confusingly similar name and trade dress to Starbucks.

Likewise, in Republic Technologies (NA), LLC v. BBK Tobacco & Foods, LLP, a jury found that consumers were likely to confuse two rolling paper brands with red lettering, but not the packaging with brown lettering. This was the case despite a prominent display of the brand names in large letters. The jury heard expert testimony that consumers are likely to make quick decisions and not pay much attention when choosing rolling papers. The jury also heard testimony from brand representatives that retailers have asked if OCB is a RAW product.

Tip No. 3: Choose a unique name and trade dress that are clearly distinct from existing products in the marketplace. Before deciding on a brand, cannabis businesses should conduct due diligence to determine if a consumer is likely to confuse the brand with another brand for a similar product. If you want to reference or parody a well-known brand, a licensing agreement with the owner of the existing brand will be necessary to avoid a trademark infringement claim.

Pitfall No. 4: Waiting for Regulatory Changes

In 2024, the Department of Justice proposed rescheduling marijuana from Schedule I to Schedule III under the CSA. If finalized, this will significantly alter the current federal approach to cannabis and might open the door to USPTO registration for cannabis brands.

Waiting for such monumental regulatory change before protecting cannabis intellectual property (IP) could prove disastrous. If rescheduling occurs, there may be a rush to the USPTO to register cannabis-related trademarks, and some cannabis brands may be boxed out or forced to fight to register a mark they have been using for years.

Tip No. 4: Do not wait to protect cannabis IP. Proactively register marks for ancillary goods and services to serve as a placeholder for marks for cannabis-related goods. This may help establish priority and protect a brand name before the market opens. As an illustration, successfully registering rolling papers or pipes may cause a USPTO examining attorney to find a likelihood of confusion when reviewing a later-filed application for a similar mark on cannabis products.

Conclusion

Trademark protection in the cannabis industry is complex and still evolving, but building a strong legal foundation now will give your brand staying power. First, determine whether your products are eligible for federal protection. For others, pursue state or common law protection. Choose original names that will not be confused with existing brands, and do not delay action waiting for a shift in regulatory regimes.

Search

RECENT PRESS RELEASES

Related Post