5 reasons the Fed may not raise rates in 2015

October 30, 2014

EDITOR’S NOTE: The following was written by Ron Insana and originally appeared in his newsletter “Insana’s Market Intelligence.” More information can be found here

In June of 1984, I began working at the Financial News Network, the forerunner of CNBC, as a lowly production assistant. I had no formal training in economics, markets or finance, so this post-graduate gig was a true eye-opener.

As soon as I arrived, I was responsible for watching the news wires, ripping scripts and getting the occasional cup of coffee for someone more senior than I. But I was also privy to listening in on a language that I had never heard before: “Fed Speak.” In those days, when Paul Volcker ran the Federal Reserve, the nation’s central bank was so opaque that Rolling Stone magazine writer, William Greider, published a tome called “The Secrets of the Temple,” which fed the conspiracy theorists that the Fed was an institution accountable to no one and was dealing in all manners of conspiratorial and clandestine undertakings.

More to the point, however, was that since the Fed rarely told markets what it was doing, while it was doing it, it was up to “Fed Watchers” and “Bond Market Vigilantes” to interpret the Fed’s actions IN the markets to discern what was happening with interest rate policy.

I can recall every morning, my late colleague, Ed Hart, FNN’s credit market reporter, whooping and hollering when the Fed added (or drained) money from the banking system. It was just one of many clues as to what the Fed was up to.

[Get the Latest Market Data and News with the Yahoo Finance App]

Every Thursday afternoon at 3:55 Eastern Time, Ed would go on the newsroom intercom and holler, “Five minutes to money!” That was our notice that the money supply figures would be released and give us an indication as to whether or not the Fed was allowing the money supply to grow, or forcing it to contract, a clue as to where interest rates, and thus, the economy would be going in the weeks and months ahead.

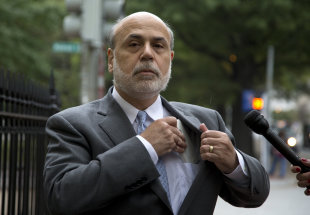

Thus, a cottage industry of “Fed Watchers” earned a nice living on Wall Street, reading the Fed’s tea leaves and giving investors a heads up on changes in interest rate policy. The Fed, by the way, would confirm changes in policy AFTER the fact, by announcing that it had raised or lowered rates, typically late on a Friday afternoon. Flash forward to today, with all the transparency at the Fed, market watchers, investors and the chattering classes still have difficulty divining the Fed’s intentions, despite historically clear signals from the likes of former Fed Chair, Ben Bernanke, and now, his successor Janet Yellen.

I don’t find the exercise all that difficult, since I tend to take key members of the Fed at their word. It has been fairly plain to me that interest rates are likely to stay low for longer, than be raised, sooner rather than later. Indeed, I am coming to the conclusion that despite all the debate about whetheror not the Fed will raise rates, next year … in the spring, summer or fall, I am beginning to believe the Fed may not raise rates AT ALL … at least in 2015.

There are five reasons why I believe the Fed may put off that day of reckoning. If I am right, such a prediction will have enormous implications for the stock and bond markets here at home and many markets around the world as well.

Fear of 1937

Ben Bernanke is well-known to have studied the policy errors made in 1937 when the Fed raised interest rates after five years of recovery from the first leg of the Great Depression. The hike in rates, coupled with

tax increases, led to a renewed downward spiral in the U.S. economy that led to the Great Depression: Part II. Bernanke, and other prominent members of the Fed, including its current chair, Janet Yellen, also studied the inconsistent policies of the Bank of Japan over the last 24 years, policies which failed to revive the Japanese economy in the wake of the burst stock and property market bubbles experienced in 1990.

Japan’s lost decades have been home to persistent deflation, which turned the Land of the Rising Sun into a land of permanent twilight. Against that deeply concerning backdrop, Charles Evans, president of the Chicago Federal Reserve, made the case recently that the Fed should wait until 2016 to raise interest rates since the economy is far from reaching the its dual mandate of maximum employment and stable inflation. Evans, who will be a voting member of the Fed policy-setting committee next year, (regional presidents rotate as voting, and non-voting members, of the FOMC on an annual basis) is a known dove. He is among those who fear the consequences of a premature “normalization” of interest rate policy.

With two inflation hawks set to depart the Fed soon, Philadelphia’s Charles Plosser and Dallas Fed President, Richard Fisher, the Fed may have a more unified, and thus dovish, view of monetary policy, consistent with the concerns of those who worry about a repeat of past policy mistakes.

Dollar domination

The U.S. dollar has appreciated quite markedly in recent months, climbing to multi-year highs against the yen, the euro, the pound and a host of emerging market currencies. Some of this can be attributed to expectations that will begin to normalize policy, even as the European Central Bank, the Bank of Japan and other central banks ease policy further. The divergent paths of interest rates, with dollar-denominated bonds yielding more than other sovereign debt, is inviting global investors into dollar-based vehicles and, as a consequence, pushing the value of the greenback to unexpectedly lofty levels.

From my vantage point, and I have been a dollar bull since spring, the dollar will continue to rise. The relatively strong performance of the U.S. economy when compared to the rest of the world, the interest rate differentials previously mentioned, and the relative safety and stability of U.S. markets make the dollar (and dollar-based markets) quite attractive to global investors.

The net effect of a strong dollar is many-fold. It drives down imported inflation (though that view has been challenged by some recent research from the Cleveland Fed), it pushes down commodity prices, again, putting a lid on inflationary pressures, and a stronger dollar is an implicit tightening of monetary policy, relieving the Fed of some pressure to raise rates sooner, rather than later.

Commodity crunch

Although you might never notice it unless someone points it out, commodity prices, despite the constant drumbeat about the dangers of incipient inflation, have fallen sharply over the last several months. And, this has occurred in the midst of a drought, geopolitical tensions, easy Fed policies and indeed, zero interest rate policies in 60 percent of the world’s economies!

Gold bars are stacked at a safe deposit room of the ProAurum gold house in Munich March 6, 2014. REUTERS/Michael …

Yet, oil, copper, wheat, gold, silver and other “stuff” is substantially lower in price than earlier this year. This not only leads to lower “headline” inflation, but leads to lower prices down the road, driving inflation below the Fed’s two percent policy goal. Indeed, the Fed’s preferred measure of inflation, the Personal Consumption Expenditures Deflator (say that three times fast), or PCE Deflator, for short, is running at a 1.5 percent annual clip. In other words, for 28 consecutive months, inflation has been below the Fed’s target. That is also true in other developed economies, namely, Europe, Japan, Russia and to a lesser extent, China. All this means is that a premature rate hike from the Fed could lead not only disinflation, but potentially deflation, both at home and abroad. This is exactly what the Fed successfully fought against for the last five years. It has no intention of re-creating an environment where the economy weakens to such an extent that deflation, again, rears its ugly head. Europe, Japan, Russia and China may all fight deflation in the months ahead — another global factor the Fed could be forced to consider before raising interest rates.

Slow/no global growth

Speaking of which, the global economy, ex-U.S., is growing more slowly than at any other time in the last five years. Europe, for all practical purposes, is in recession. Japan has suffered a serious decline in growth, thanks to the imposition of a consumption tax, the second round of which will be levied next year, despite the negative consequences of round one. China is growing far more slowly than official statistics suggest. The Chinese government has all but admitted it may abandon its official 7.5 percent growth target as it attempts to reform its economy.

The weakness in China has shown up in falling prices for basic materials like nickel, copper and oil, suggesting that we are entering a period of slower global growth as demand for raw materials declines. Russia is on the brink of recession. Its main stock market gauge is down 21 percent from its June 24 peak, signaling a bear market there. Its currency is unstable as are the financial markets in Ukraine. Brazil is growing more slowly than anyone expected. Argentina is on its back, while the rest of Latin America with the exception of Mexico, is struggling.

While the Fed does not make policy based on the behavior of non-US economic activity, it also knows that it is the de facto central bank for the entire world. Creating a negative feedback loop by raising interest rates here could circle back to bite the US economy if there is no synchronized acceleration in global growth.

Geopolitical risk

It’s not new that the world is a dangerous place. But for the first time in sever-al years, the proliferation of geopolitical hotspots around the world threatens global growth. In a cold Russian winter, Moscow can effectively turn off the heat for Ukraine, Eastern and Western Europe, should it decide to further retaliate for

The murderous advance of the Islamic State has forced more than 1.7 million people in Iraq from their homes. The …

Western sanctions levied against it. The battle against ISIS; the on-going war between Israel and Hamas; disputes over the South China Sea among China, Japan and Vietnam, could all destabilize not just the geopolitical order, but the global economy as well. Again, the Fed can’t control this anymore than it can control the weather, but a global event of some scale could keep the Fed sidelined until the geopolitical picture becomes clearer.

So, while most market participants are arguing over whether the Fed raises rates in March, or June, I am arguing that the Fed will have ample reason to wait beyond those dates, as it takes into account ALL the above-mentioned factors. In short, while I believe it is not safe to own bond funds, which have no inherent maturity date, or stretch for yield in the junk bond market, I also don’t believe that bonds will suffer greatly over the next year. Certainly a rapid acceleration of growth, wage inflation and greatly reduced underemployment could change all that … the Fed IS data dependent after all, and I doubt that is the most likely outcome over the next 12 months.

The trend remains firmly toward disinflation at home and deflation abroad. The US will likely continue to expand GDP at a slow and steady pace … and the rest of the world … not so much. US large cap stocks, with a decidedly domestic focus, clean balance sheets, excess cash and a commitment to dividends hikes and stock buybacks, may still be the best bets in the world.

In any event, despite the repeated cries of the Fed bashers, the inflation hawks, the dollar bears and the gloom-and-doomers, I believe the Fed will stay the course for some time to come … at least until it is quite clear to them that the above-mentioned factors will cease to be a restraint of the Fed’s goal of getting nearly everybody back to work, and engineering enough growth that inflation grows in a manner consistent with its mandate.

This is not your grandfather’s Fed and we should be thankful for that!

Search

RECENT PRESS RELEASES

Related Post