‘A very camp environment’: why Alan Turing fatefully told police he was gay

March 8, 2025

For decades, it has puzzled historians. Why, in the course of reporting a burglary to the police in 1952, did the maths genius Alan Turing volunteer that he was in an illegal homosexual relationship? The admission enabled the police to prosecute the Bletchley Park codebreaker for “gross indecency”, ending Turing’s groundbreaking work for GCHQ on early computers and artificial intelligence and compelling him to undergo a chemical castration that rendered him impotent. Two years later, he killed himself.

Now, research by a University of Cambridge academic has shed light on the reasons why Turing, a former undergraduate and lecturer at King’s College, Cambridge, did not hide his homosexuality from the police. “There was a whole community in King’s quite different from stories one knows about from gay history, usually involving casual pickups and a lot of despair, hiding and misery,” said Simon Goldhill, professor of classics at the college.

His research has uncovered a “rather happy” community in the formerly all-male college at “the centre of the British establishment” while homosexuality was still illegal. “It was a very camp environment,” said Goldhill, who will talk at King’s 11 March about his new book, Queer Cambridge. For example, in the 1930s, when Turing was at King’s, “the provost [college principal] and many of the senior fellows [tutors] were openly and outwardly gay. They had sex with men and talked constantly about having sex with men.”

Turing spent his formative years – from 18 to 24 – at King’s, learning it was “perfectly acceptable” for intellectual gay men like him to not hide their sexuality around people in positions of power. As a result, in 1952 Turing told the police the suspected burglar was a friend of his male lover. “Turing thought he had the perfect right to be gay. He wasn’t ashamed of it. It was who he was.”

His experiences of gay life at King’s were empowering: “He’d had a relationship at school and people had been worried about that. So when he came to King’s, where it was perfectly acceptable to be homosexual, I think that’s when he developed himself as a gay person.”

Turing gained a “political strength and a political clarity” from his time at King’s. “He was somebody who was capable of standing up for himself as a gay man. He thought it was important not to lie, not to conceal, but to say: ‘This is who I am. I think you should be able to deal with this.’ He got that confidence from King’s.”

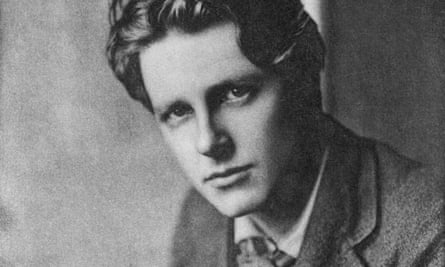

The poet Rupert Brooke and the author EM Forster are among the other gay alumni of the college, along with the economist John Maynard Keynes, who was a fellow at King’s alongside Turing.

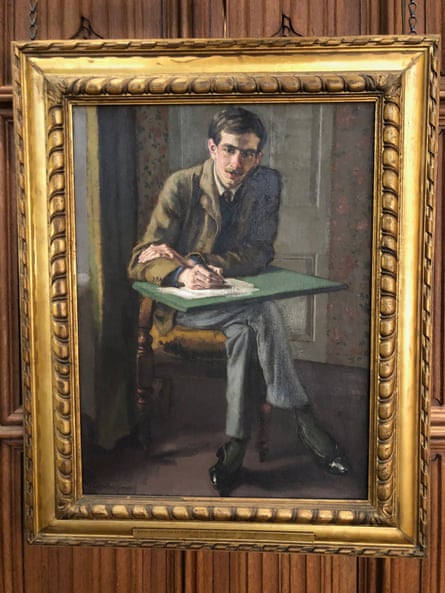

Keynes kept ledgers of every man he slept with and what he did with them for years, Goldhill said. “He’s an economist – and economists count things. He’s bookkeeping.”

Keynes also wrote about how everyone in Cambridge was “buggering each other”. Virginia Woolf, a friend of Forster, Keynes and the theatre director Dadie Rylands, another gay fellow of King’s, claimed: “The word buggery was never far from our lips.”

Goldhill said: “There’s that extraordinary sense that it was very much talked about and open. You’ve got a complete gay community at the centre of the establishment, with Keynes and leading figures in economics, literature, music and art in charge.”

The gay community at King’s is likely to have its roots in a statute, signed by King Henry VI in 1443, which required King’s to exclusively admit students from Eton College. “Coming from one house in Eton, the undergraduates had already lived together as boys. They knew each other for ever,” Goldhill said. “There was a very strong community among them – and that carried on.”

Such intense childhood bonds meant students who desired other men were tolerated “within the safety of the college walls”.

Gay men who came to King’s as “pretty young” students and stayed on to become powerful academics were able to have romantic relationships throughout their lives, ensuring the gay community at the college thrived. Unlike other gay histories, these men not only had “a sense of continuity of time and place, but a sense of moving through different stages of relationships as a gay man,” Goldhill said.

After the statute requiring Etonians was overturned in the 1860s, teachers at other schools began encouraging bright boys whom they knew or suspected were gay to apply to King’s, where they would get in and “have a good time”, Goldhill said.

To this day, King’s has a reputation for being the centre of LGBTQ+ life in Cambridge, Goldhill said. “There has been and remains a spirit of tolerance and liberal values about the place – though even here, these days, such values are under threat.”

King’s LGBTQ+ student officer Ainoa Cernohorsky said that while queer students at Cambridge are always fighting for more space to be themselves, “I have not encountered, seen or felt anything but unwavering support for my queerness – and for my role as the LGBTQ officer – from queer and non-queer undergraduates, graduates, professors and directors of studies at King’s. It’s a very accepting environment, and I think that’s partly due to the way the college presents itself and the stories it chooses to platform.”

There is a prominent Antony Gormley statue dedicated to Turing in the college grounds, while a painting of Keynes by his lover Duncan Grant hangs proudly next to paintings of Forster and other gay fellows in the grand college dining hall. “These people are present in my mind,” said Cernohorsky. “They left their mark on the atmosphere in King’s.”

Search

RECENT PRESS RELEASES

Related Post