Environment: Will Labor now protect our environment? If not now, probably never

May 10, 2025

The world is getting hotter, seas are rising more quickly, oceans are heating faster and freshwater is getting saltier, but Labor’s first-term environmental performance provides little optimism for its second, even though Australia leads the way with solar energy generation.

Doubtful Labor will get serious about the environment even now

Over the last three years, I have been disappointed by Labor many times, particularly with Anthony Albanese’s unwillingness to make, with one or two exceptions, hard decisions. But when asked whether I thought Albo was doing a good job, my response has always been the same, “He’s made it clear all along that his primary goal was to get re-elected. Ask me the day after the election whether he got it right.” Just like in 2022, Albo got it right. Labor has been re-elected with a thumping majority, but whether that is an endorsement of its rather timid approach in many policy areas over the last three years or mostly modest proposals for the next three is anyone’s guess.

What we do know from Labor’s first term of government is not at all reassuring that it will be more aggressive in tackling environmental issues over the next three years.

For instance, we know that Labor strongly supports the rollout of renewable energy within Australia, is completely opposed to nuclear power and would love to host a COP Carnival.

But it is equally clear that the Party does not have any appetite for:

- Strong action to reduce greenhouse gas emissions either within Australia or internationally;

- Any action to reduce Australia’s coal and liquified natural gas exports;

- Reducing fossil fuel subsidies or ensuring that coal and gas companies pay appropriate royalties and tax; or

- Strong environmental protection laws and mechanisms to implement them.

Any environmental policies, including any that tackle the biodiversity crisis, that might damage Australia’s economy or their own electoral prospects.

In summary, Labor has been happy to make the easy decisions about the environment and the energy transition but not at all prepared to take on any vested interests. Taking their lead from the government’s half-hearted approach, many Australians remain unconvinced that we face urgent and serious environmental challenges and/or that (“little”) Australia should be making a significant contribution to tackling these.

I’ll be delighted if I am proven wrong, but I am not optimistic that dominance in the House of Representatives will embolden the prime minister and the ALP to rise to the challenges. I think we must look to the Greens and Independents in the Senate to demand a high price for their support of the government’s whole political agenda.

Sea level is rising faster and faster

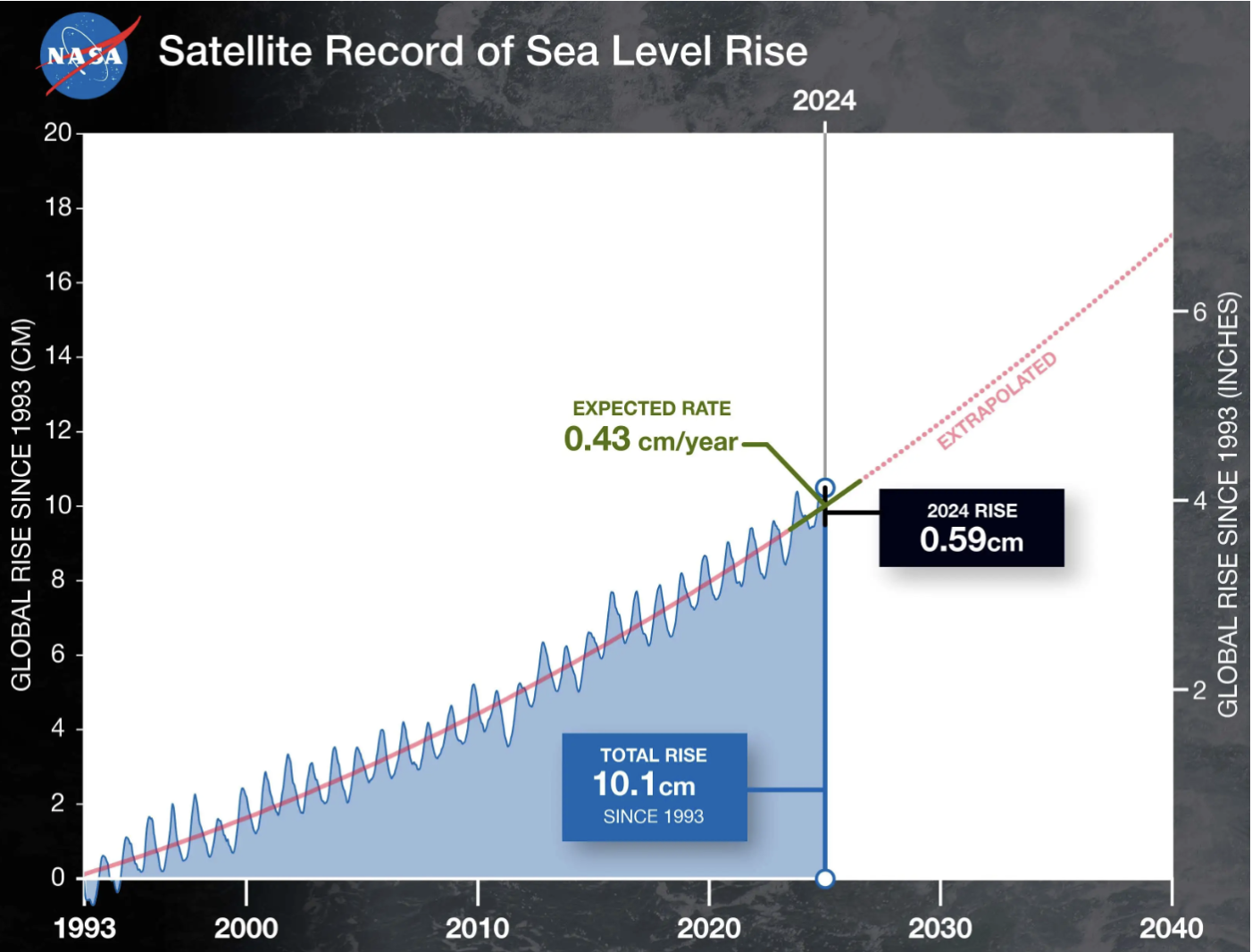

In 2024, the

global sea level was 10.1cm higher than in 1993. It is not news that the sea level has been rising as a result of global warming. Nor is it particularly newsworthy that the rate of sea level rise has been steadily increasing since 1993. The annual rate now (4.7 mm/year) is more than double what it was in the 1990s (2.1 mm/year). The increasing steepness of the red trend line in the graph below is evidence of this.

More newsworthy is that in 2024 the increase (0.59cm) was even higher than the expected increase (0.43cm), based on recent experience.

Also worthy of note is that in recent years about two-thirds of the sea level rise has been due to the addition of water to the oceans from melting ice sheets and glaciers and about one-third from expansion of the progressively warmer sea water, but in 2024 (the world’s warmest year on record, see below) the relative contributions flipped, with two-thirds due to thermal expansion.

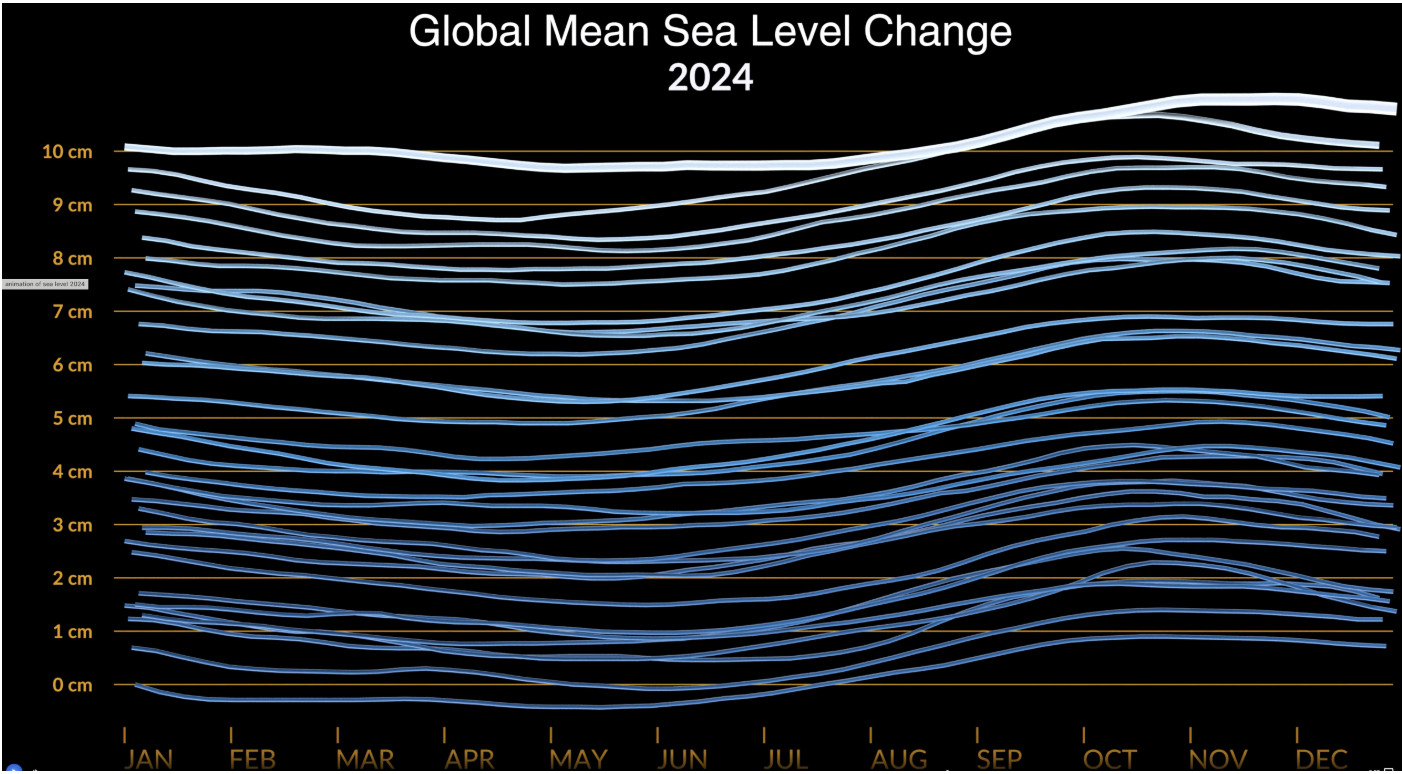

The saw-tooth pattern in the graph above is due to the average sea level being higher during summer in the Southern Hemisphere, which is 81% ocean, than during summer in the Northern Hemisphere, which is only 61% ocean. This annual pattern is illustrated in the snapshot below from the animated graphic in the linked article. The blue lines in the snapshot show the sea level rise during each year from 1993 to 2024. The 1990s are all at the bottom and recent years are all at the top, but it’s much easier to see both the annual pattern and the rising sea level if you watch the animation.

… and the oceans are heating faster and faster

Only 5% of the heat that has been added to the Earth as a result of global warming has been stored in the land. Just 1% has been stored in the atmosphere and 4% has warmed and melted glaciers and ice sheets. The vast majority (90%) has been stored in the oceans and the last eight years have each set a record for ocean heat content.

Like sea level rise, the change is speeding up. The average rate of ocean warming over the last 20 years has been more than double what it was between 1960 and 2005. Of most concern for future generations, is that warming of the oceans will continue for centuries even after greenhouse gas emissions cease. As a result, sea levels will continue to rise for centuries after emissions reach zero – although there may not be enough humans still alive at that time to be doing the measuring.

Ocean warming may sound fine if you like a tepid swim, but it has disastrous consequences: degradation of marine ecosystems, loss of biodiversity, reduced fishing yields, reduction of the ocean’s ability to absorb CO2 from the atmosphere, more severe tropical and subtropical storms and loss of polar sea ice. Some of these effects are exacerbated by the coincidental acidification of the oceans caused by the increasing amount of CO2 they are absorbing from the atmosphere.

Did the hottest year on record breach the Paris Agreement?

Mainstream media reports that 2024 was more than 1.5oC warmer than the pre-industrial average have been so widespread that I haven’t seen any need to draw more attention to it. It has also been widely reported that scientific and diplomatic climate change authorities have been keen to emphasise that this does not mean that the Paris Agreement’s target of keeping global warming under 1.5oC has been exceeded. Rather, the argument goes, it’s the average over a longer period (say, 20 years) that matters, not an individual year. That said, neither the environment nor the laws of physics care two hoots about the Paris Agreement. So, alarm that the Agreement’s target has been exceeded and protestations that it hasn’t are purely political and performative.

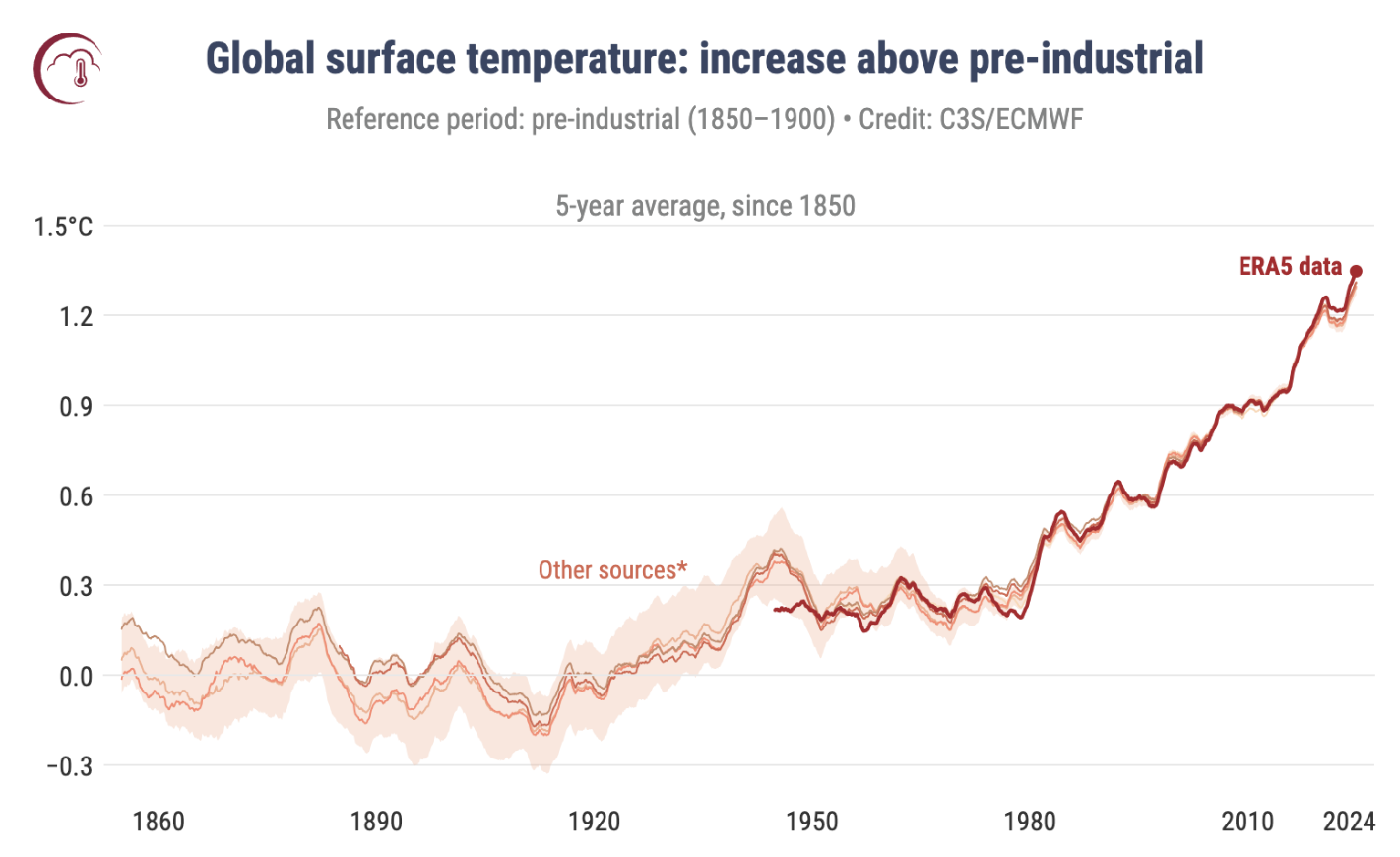

Nonetheless, let’s have a look at how the rolling

five-year average global temperature since 1850 compares with the average for 1850-1900 (the pre-industrial level for this study):

Between 1850 and around 1920 the five-year average hovered around the 1850-1900 average (i.e., the difference averaged roughly 0oC over the 70-year period). Over the 60 years between 1920 and 1980, the difference went from 0oC to 0.3oC and in the 44 years between 1980 and 2024, the difference increased by a further 1oC to 1.3oC. My personal extrapolation of the data is that the five-year average will exceed 1.5oC in about 2030 and that the 20-year average will hit that mark in the mid-2030s. However, as there’s good evidence that the rate of warming is increasing, the two dates may be sooner.

For readers who would like some reasonably digestible summaries of global warming in 2024, the following are pretty good:

‘What we learned from the hottest year on record’, ‘These graphics help explain what climate change looked like in 2024’, and “WMO State of the global climate 2024”. The last includes a punchy two-minute video summary that contains the following assessment: “A single year above 1.5oC of warming does not mean the long-term goal of the Paris Agreement is dead. But it is on life support.”

Salinisation of freshwater

A few weeks ago, I highlighted the risks posed to supplies of freshwater by higher temperatures in the

world’s mountainous regions. Another risk to our freshwater supplies is increasing salinisation arising from increasing salt pollution from the land, lower flows of freshwater and intrusion of saltwater from the sea.

Freshwater Salinisation Syndrome, which involves multiple salts and ions, not just sodium chloride, sets up multiple chain reactions which can cause scaling and erosion of water pipes and infrastructure, change the pH of water in ways that harm aquatic life and crops, change the breakdown of organic matter and the cycling of carbon, alter the survival of harmful bacteria, increase the formation of algal blooms and even increase the emission of greenhouse gases. The effects can be seen from the headwaters of rivers to tidal areas and influence many of the “ecosystem services” that humans rely on for health and survival.

Australia leads in solar and wind energy generation

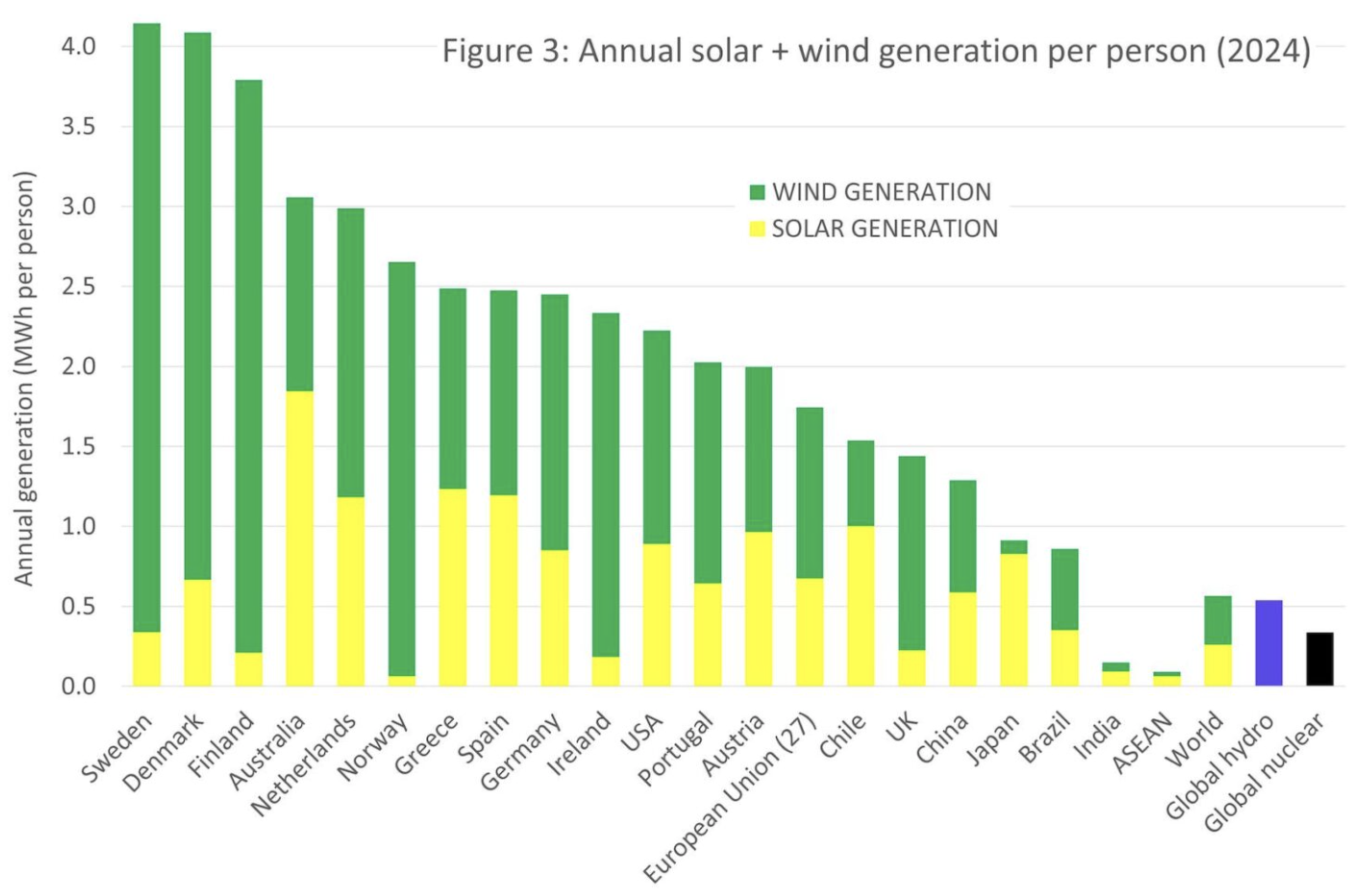

Australia produces more

solar energy per person than any other country. We’re more middle-of-the-pack when it comes to wind energy, completely blown away by the Scandinavians. Combining the two, we come fourth. (The original data is in a report by

Ember.)

Search

RECENT PRESS RELEASES

Related Post