Solar apprenticeships give Virginia students a head start on clean…

May 21, 2025

This article is part of a series about rural clean energy workforce development.

Read more.

Powering Rural Futures: Clean energy is creating new jobs in rural America, generating opportunities for people who install solar panels, build wind turbines, weatherize homes, and more. This five-part series from the Rural News Network explores how industry, state governments, and education systems are training this growing workforce.

When Mason Taylor was getting ready to graduate from high school in 2022, he thought he would have to take an entry-level technician job with a company in Tennessee.

Taylor grew up in the town of Dryden in rural Lee County, in the westernmost sliver of Virginia between Kentucky and Tennessee. He had come to love the electrical courses he took in high school because there was always something new to learn, always a new way to challenge himself.

Driving to Tennessee for work would likely mean two hours commuting each day.

Taylor, now 21, just wanted to work close to home.

A summer apprenticeship learning how to install solar arrays helped him get on-the-job training and opened up connections to local work.

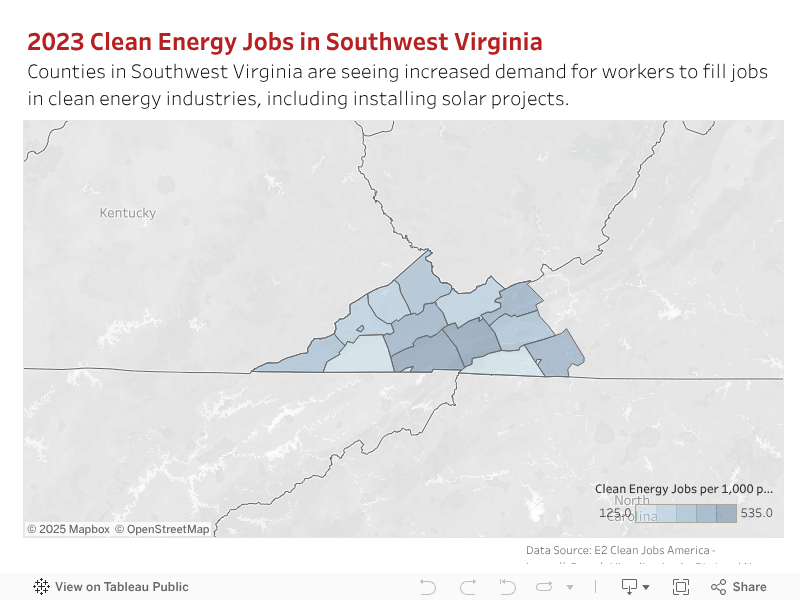

Virginia ranks eighth in the nation for installed solar capacity, according to the Solar Energy Industries Association, but so far, major renewable energy projects have been clustered in the eastern and southern regions of the state. Increasing the popularity of solar power in the far southwestern corner of the state depends in part on the availability of trained workers like Taylor.

Andy Hershberger, director of Virginia operations for Got Electric, said the electrical contractor firm has had an apprenticeship program nearly since the company’s founding.

The company, which has about 100 employees total, with 40 in Virginia and an office in Maryland, has worked with Staunton-based Secure Solar Futures, a commercial and public-sector solar developer, as far back as 2012.

More recently, the two companies began working to set up a training program that was more focused on solar. The catalyst was the former superintendent of Wise County schools, a school division that had signed up to put solar panels on its facilities. The superintendent saw the installation as an opportunity to get his students hands-on work on a renewable energy project.

Approximately three dozen apprentices have signed up for the program since 2022, including about 13 who are currently involved, Hershberger said. They work on a variety of solar projects, including on rooftops, carports, and ground-mounted installations.

“We have been utilizing this program to train students coming out of high school and basically growing the workforce side of this thing, so we have the necessary personnel to build these solar projects long term,” Hershberger said.

On top of hourly pay, apprentices get free equipment and a transportation subsidy, along with nine community college credits at Mountain Empire Community College, which provides classroom training before students step onto the job site.

“I mean, pretty much everything you need to know to go out and do any electrical job, you pretty much learned in that apprenticeship program,” Taylor said.

He was in the first cohort of 10 students who installed solar panels on public schools in Lee and Wise counties in 2022. A grant from a regional economic development authority paid the students’ wages while they earned credit at Mountain Empire Community College, which serves residents of Dickenson, Lee, Scott, and Wise counties, plus the city of Norton.

He got a job offer from Got Electric at the end of that summer.

This summer, Secure Solar Futures and Got Electric will join forces again to install more than 1,600 solar panels on the community college’s classroom buildings. The project was originally slated for 2024 but was delayed due in part to a separate project upgrading fire safety equipment in one of the buildings.

The 777-kilowatt solar power system will be connected to the electric grid, and Mountain Empire will receive credit for the power it generates.

Hershberger said he sees interest in solar growing.

“I think there’s always been folks that have adopted renewable projects, different types of energy sources. There’s always the standard interest in trying to save money for facilities and campuses and things like that,” he said.

Mountain Empire Community College offers solar training as a standalone career studies certificate or as part of its larger energy technology associate degree program.

In Southwest Virginia, a solar installation project is more likely to consist of adding panels to homes and businesses rather than building the large, utility-scale ground-based facilities more commonly seen in Southside Virginia, said Matt Rose, the college’s dean of industrial technology.

On a larger project, a single worker might have a specialized role, performing the same task across a large number of panels. On a smaller project, a worker is more likely to be involved in more aspects of the job.

“Our students need to have that comprehensive understanding and ability to be able to do it all,” he said.

Last year, 10 students graduated Mountain Empire with the solar installer certification. Many students who earn the certification perform solar installation work as one part of a more comprehensive job, such as being an electrician.

Rose said the college’s students typically start out making $17 or $18 an hour but can earn more as they become journeymen and master electricians.

Nationwide, the median salary for electricians is about $61,000.

In Lee County, population 22,000, the median household income is about $42,000.

The number of solar installers in Southwest Virginia is unclear. The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics doesn’t collect data on employment by technology, so residential solar installation companies are labeled as electrical contractors, along with all other electrical businesses, according to the U.S. Department of Energy.

Tony Smith, founder and CEO of Secure Solar Futures, measures the success of the company’s apprenticeship program person by person. At an April event to celebrate the completion of the first phase of solar panel installation for Roanoke schools, Smith asked about several of the students from the 2022 cohort from Lee and Wise counties by name.

Smith said it’s tough to replicate the apprenticeship program at various school divisions. Doing so requires the work of individual school systems and the regional community colleges, instead of being able to pick up the curriculum from one area and apply it at the next project site.

And all the partners — Smith’s company, participating schools and installation firms — face some uncertainty for each project. It’s challenging to pinpoint the timing of projects so that students have the time to participate during the summer months, he said.

Solar training can give students a “head start on everybody”

“The things I learned in the apprenticeship program I’m still doing day to day,” Anthony Hamilton, 21, said. He completed the eight-week apprenticeship in Lee and Wise counties in 2022 alongside Taylor. He didn’t think it would turn into a full-time job. He doubted anyone really wanted to hire a kid just starting college.

He’s been with Got Electric ever since, working as an electrician primarily on commercial jobs. Hamilton’s solar experience has come in handy on recent installation projects at a poultry farm and at a YMCA facility.

Hamilton continued going to school at Mountain Empire and graduates this month with two associate degrees in energy technology and electrical. He’s also earned a handful of certificates in solar installation, air conditioning and refrigeration, and electrical fabrication, among others. With the nine credits he earned in the summer apprenticeship, he “already had a head start on everybody in the program.”

It wasn’t an easy journey, though.

He said he usually started his day around 6 a.m. and went to night classes after work that stretched until 9:30 p.m. Hamilton lives in Coeburn in Wise County, a 45-minute drive to the college campus. He’d get home late, then get up early and do it all over again. But his college was free through a local scholarship program that pays for up to three years of classes at Mountain Empire.

He’d like to stay with Got Electric and start preparing to take his journeyman’s license, which requires at least four years of practical experience on top of vocational training, plus an exam. From there, he’s got designs on moving up in the company and eventually becoming a master electrician.

On April 14, he was in the town of Abingdon, a few weeks into a three-month project installing a solar array at a large poultry farm that says it produces more than 650,000 eggs a day. The work so far entailed digging trenches and laying PVC pipe for the ground-mount solar system that will span one section of the farm’s expansive fields.

Taylor uses similar skills at work each day. But his work site looks a lot different from Hamilton’s.

It has taken Taylor some time to figure out how to stick close to home while working in his trade. He spent a year working with Got Electric immediately after finishing his summer apprenticeship, then left the company to work as an electrician in a local school system. He eventually returned to Got Electric for a few months, working at Virginia Tech putting solar on three buildings on campus in Blacksburg, three hours from home.

He discovered he didn’t like traveling for installation jobs that meant night after night in a motel room.

“That was the only complaint I had with it, about being away from home,” he said.

Now he’s an electrician at a state prison in Big Stone Gap. He has the same shift every day, in the same place, and drives 10 minutes home from work at the end of the day.

Taylor has also taken additional classes at Mountain Empire and wants to go back this fall to finish his associate degrees in HVAC and electrical. He eventually wants to open his own business as an electrician working locally. He’d like to be able to do small solar installation jobs. Solar hasn’t really caught on in far Southwest Virginia, he said — at least, not yet.

Rose, the dean at Mountain Empire, noted that once major solar projects are done, maintenance doesn’t require ongoing jobs, and most students who receive training in solar installation typically make it part of another job, such as being an electrician.

“We’re starting to see a lot more homeowners interested in [solar] locally as a way to offset increasing energy costs, but overall most of it is just a component of the job because there’s not enough demand,” Rose said.

Rose predicts interest in solar will grow as more homeowners and business owners look for ways to offset rising electric bills.

“As we all look at increasing energy costs, it’s going to make a lot more economic sense,” he said.

Energy independence, he added, fits with the character of Southwest Virginia.

“We’ve always been resilient people,” Rose said. “We’ve always been adapt-and-overcome people, and what better way than to basically control a little bit of your own power?”

This reporting is part of a collaboration between the Institute for Nonprofit News’ Rural News Network and Canary Media, South Dakota News Watch, Cardinal News, The Mendocino Voice, and The Maine Monitor. Support from Ascendium Education Group made the project possible.

Matt Busse

covers business for Cardinal News.

Lisa Rowan

covers education for Cardinal News.

read next

Search

RECENT PRESS RELEASES

Related Post