The role of educational science in environmental management and green technology adoption

June 3, 2025

Abstract

This study examines the role of educational science in rural environmental management, focusing on its contribution to the adoption of green technologies and exploring how these innovations can drive rural revitalization and advance dual-carbon objectives. The research involved qualitative interviews with 30 stakeholders, including primary and secondary school teachers, environmental protection practitioners working in rural areas, village administrators, and local residents from four rural villages in central China. The findings highlight the significant impact of education on environmental awareness and behavioral norms among rural residents, although its practical application remains constrained. Respondents emphasized the importance of aligning educational content more closely with rural realities, especially in relation to persistent pollutants, green agriculture, energy conservation, and emission reduction. Despite the potential for education to promote environmentally friendly technologies, significant barriers include the lack of instructional resources, high costs, and limited support from local residents. The study advocates for a holistic approach to promoting green technologies, which includes the development of tailored educational policies, the enhancement of teacher training in environmental education, and the alignment of educational content with rural revitalization and dual-carbon objectives. Future research may explore how sustainable environmental education might help communities navigate the tension between financial constraints and environmental targets.

Introduction

Study background

Rural ecosystems face growing pressure due to climate change and uneven resource distribution from past industrial policies1. Problems like polluted irrigation water and collapsing ecosystems now threaten food supplies, public health, and long-term environmental stability2. Yet the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals highlight a practical solution: education. By teaching farmers sustainable land-use techniques and connecting classroom learning to community action, we can rebuild trust in environmental stewardship. This isn’t just about spreading awareness—it’s about giving people the hands-on skills they need to farm sustainably, ensuring their livelihoods thrive alongside natural ecosystems3.

The coordinated integration of China’s Rural Revitalization Agenda (2017) and the Dual Carbon Agenda (2020) forms a policy framework for sustainable rural governance. This framework prioritizes educational initiatives designed to upgrade rural infrastructure, advance precision agriculture adoption, and cultivate specialized agricultural entrepreneurs4. The dual-carbon strategy mandates rural areas to achieve peak carbon emissions by 2030, posing challenges in addressing high carbon outputs from conventional farming while creating opportunities for renewable energy adoption and low-carbon technological innovation5. Empirical studies reveal that farmers participating in structured environmental education programs demonstrate significantly higher rates of adopting agroecological practices, underscoring education’s critical role in catalyzing technological and behavioral transitions.

Core concept definition and synergistic mechanisms

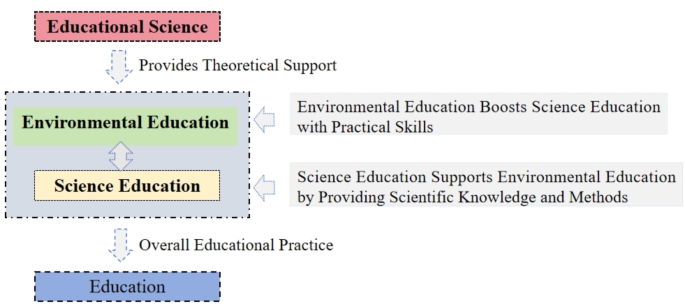

A comprehensive three-dimensional conceptual framework with coherent logical underpinnings (Fig. 1) is established through this study. As a foundational interdisciplinary field, Educational Science elucidates pedagogical principles through systematic analysis of educational phenomena, thereby informing evidence-based practice. Its foundational significance lies in reconciling epistemological divides between Environmental Education and Science Education6. ​Particularly​, Environmental Education endeavors to enhance ecological literacy, foster civic responsibility, and catalyze sustainable behavioral shifts by operationalizing theoretical insights from Educational Science through situated learning experiences7; conversely, Science Education concentrates on developing systematic scientific knowledge frameworks, methodological competencies, and technological problem-solving skills, thereby equipping Environmental Education with analytical rigor and empirical research protocols8. This reciprocal relationship engenders a symbiotic dynamic wherein Science Education professionalizes Environmental Education via knowledge dissemination, while Environmental Education enriches Science Education’s localized adaptability through community engagement. The resultant paradigm of reciprocal empowerment functions as the primary catalyst for educational systems’ transition toward sustainable development agendas. Specifically, Educational Science establishes a comprehensive knowledge framework for environmental governance at the theoretical level, informing curriculum development and pedagogical innovation in Environmental Education; Science Education incorporates STEM-based curricula at the practical level to enhance farmers’ capacity to implement low-carbon technologies; Environmental Education facilitates knowledge contextualization through localized workshops and culturally responsive materials development at the community level.

Figure 1 illustrates three key interconnected pathways in rural green development. First, educational science builds basic knowledge systems for environmental management by establishing cognitive foundations. Second, environmental education applies green technologies through a structured learning process-from understanding theories to practicing skills and adopting sustainable behaviors. Third, formal education works with governments, businesses, and community groups to create social connections and improve cooperation for long-term development9. This cross-disciplinary approach breaks down academic barriers and shows how schools act as centers for creating knowledge, sharing technology, and encouraging community action in ecologically changing rural areas.

Existing challenges and research gaps

Rural environmental education faces three main problems. First, teaching materials often don’t align with local economic and social needs, and too much focus on theory makes it hard to apply what’s learned in real life10. Second, unequal access to education has widened the gap between rich and poor areas11. Third, stakeholders like farmers and teachers have different views on how education affects the environment, but these differences haven’t been well-studied12. Although studies show that environmental education helps protect the environment, few have explored how effective science teaching methods are in practice, how curricula can be adapted to local conditions, or how to build consensus among groups with conflicting interests.

Research objectives and hypotheses

This study aims to reveal the multidimensional mechanism of the role of education science in rural environmental governance by focusing on answering the following questions:

-

(1)

Does a relationship exist between the effectiveness of science education and sustainable environmental management in rural areas?

-

(2)

How can educational materials be utilized to enhance environmental awareness and participation in rural areas?

-

(3)

What is the general agreement among farmers, community leaders, teachers, and environmentalists regarding the correlation between educational science and environmental management?

To answer these questions and based on established research12,13,14, the following hypotheses are proposed:

Hypothesis 1

There is a positive relationship between the effectiveness of science education and sustainable environmental management in rural areas.

Hypothesis 2

Educational resources suited to the socioeconomic circumstances of rural communities will dramatically increase environmental knowledge and participation.

Hypothesis 3

Farmers, community leaders, teachers, and environmentalists have very different perspectives on the role of education in environmental management, which are influenced by socioeconomic factors.

Literature review

Influence of educational science on environmental management

Education Science serves as a critical force in refining environmental governance frameworks and advancing the adoption of sustainable technological solutions. While fostering environmental literacy among the populace remains crucial, education principally catalyzes behavioral transformation through immersive learning experiences, ultimately achieving measurable improvements in ecological stewardship. A fundamental tenet of green pedagogy involves structuring curricula to systematize environmental knowledge systems, practical competencies, and value orientations that guide pro-environmental decision-making. Su et al. emphasize the necessity for educational approaches that combine theoretical foundations with practical applications, thereby equipping learners with contextually adaptable green competencies15. A significant challenge in educational practice remains motivating students to translate conceptual understanding into sustained engagement with environmental initiatives. Lamanauskas identifies attitude cultivation as a proximal determinant of behavioral plasticity16, whereas Yang et al. demonstrate through mixed-methods research that narrative pedagogy significantly strengthens pro-environmental dispositions among youth, indicating pedagogical strategies must embed learning outcomes within learners’ lived experiences to augment behavioral agency17. Furthermore, environmental pedagogy must prioritize the development of ecocivic responsibility through place-based learning paradigms, particularly in rural contexts where adapting curricula to local contexts becomes essential to address educational resource constraints18,19. Hoffmann and Muttarak’s longitudinal analysis reveals that community-based initiatives produce coordinated behavioral changes at both individual and collective levels, thereby strengthening community sustainability mechanisms20.

Educational science holds a central position in driving green technological innovation. Uvarova et al. argued that pedagogical strategies serve as critical pathways to accelerate sustainable technology adoption and spread by fostering innovative problem-solving skills and entrepreneurial vision21. Importantly, tertiary institutions emerge as vital agents for technological breakthroughs and regional sustainable development agendas22. Empirical findings from Xiuling et al. revealed that vocational training participants exhibited substantially higher implementation rates of precision irrigation and organic farming techniques, underscoring education’s instrumental role in propagating eco-friendly innovations23. Additionally, structured initiatives to refine green financing frameworks and policy design processes significantly enhance green R&D investment24. Despite these advancements, extant literature remains limited in explaining how varied educational models influence technology adoption trajectories, particularly within elementary and community-based learning contexts. Future research should employ cross-disciplinary methodologies to assess the long-term effectiveness of pedagogical interventions in promoting technological ecologization12.

Current status of green technology use in rural areas

The application of green technologies in rural areas spans four core areas: energy efficiency and emission reduction, renewable energy, sustainable agriculture, and resource circularity, playing a ​critical​ role in advancing sustainable development and alleviating environmental degradation. Energy-efficient and emission-reduction technologies, such as drip and sprinkler irrigation systems, have demonstrated exceptional efficacy in water-limited rural regions, as documented by Yang et al., who emphasize their capacity to enhance agricultural water productivity25. Moreover, energy-efficient building designs have emerged as practical approaches to reducing household energy consumption in rural settings, as evidenced by Pan and Mei Wang’s research26. In the realm of renewable energy, photovoltaic systems not only ensure stable electricity access for rural households but also lower energy costs and attract policy incentives27, while biomass technologies—including biogas digesters and straw management—provide clean energy alternatives while curbing pollution28. Within sustainable agriculture, organic and ecologically integrated farming systems contribute to ecological equilibrium by minimizing chemical inputs, as Tahat et al. highlight their role in boosting soil organic carbon content29. The Chinese fish-rice system exemplifies how agricultural yields can be increased without compromising ecological integrity30. For resource circularity, anaerobic fermentation of agricultural waste generates renewable energy and reduces pollution in rural areas31. Although significant progress has been made, the widespread adoption of green technologies remains constrained by financial limitations and technical barriers32; thus, future research should prioritize investigating the contextual variability of their environmental and socio-economic impacts across diverse cultures and economies, as well as developing innovative business frameworks to facilitate market penetration33.

Education plays a ​critical​ role in advancing green technology diffusion, with rural regions requiring heightened emphasis. Deshuai et al. argue that education enhances technology adoption by fostering public awareness of green energy solutions and ​prompting​ behavioral shifts34. Furthermore, education extends beyond knowledge transmission to facilitate green technology adoption through skill development initiatives. Research by Luo et al. highlights the instrumental role of agricultural cooperatives in advancing sustainable practices, particularly ​integrated pest management​ and ​precision irrigation​35. Higher education institutions uniquely contribute to green technology implementation through curricular integration, as empirical studies demonstrate that environmental programs strengthen interdisciplinary competencies and inspire students to deploy sustainable solutions professionally36. Li et al. posit that tertiary education accelerates green innovation and ​amplifies policy effectiveness​ in regions grappling with severe pollution37. Nevertheless, educational endeavors encounter systemic barriers, including resource constraints and bureaucratic inefficiencies, which hinder the scalable implementation of green technologies and limit the broader impact of pedagogical interventions11. Subsequently, future inquiries must integrate transdisciplinary collaborations and ​innovative teaching frameworks​ to mitigate these obstacles while incorporating emerging technologies—including artificial intelligence—for curriculum development—to optimize sustained technological adoption outcomes.

Materials and methods

Research methodology

This investigation employed a qualitative methodology to examine the intersections of educational theory and sustainable land stewardship practices within rural contexts. This approach deliberately addresses gaps identified through critical literature review: specifically, the dearth of contextually appropriate pedagogical resources for rural learners and the limited translation of ecological principles into everyday agricultural decision-making. The research aimed to collect lived experiences and achieve situated understanding of environmental challenges confronting rural populations, employing semi-structured interviews with purposively selected participants representing diverse educational roles and community perspectives.

Research subjects

We carefully chose 30 people for our study using purposive sampling to include a mix of ages, genders, jobs, and education levels, Detailed information is shown in Table 1.This mix helps us understand different views on rural environmental management. Our group includes teachers, environmental workers, village leaders, and farmers from four central Chinese villages. By studying these individuals, we aim to reveal how their daily lives and roles shape local approaches to protecting the environment.

Interview questions

To investigate the impact of education science on green technology and environmental management in rural areas, we developed the following four interview questions:

-

(1)

What are the main challenges of rural environmental management?

-

(2)

What are the specific roles of education in Raising environmental awareness?

-

(3)

What is the current status of Green Technology Use in rural areas, and what is the contribution of education?

-

(4)

What are the main barriers faced in integrating education and environmental management?

Data analysis

This study employed thematic analysis to systematically organize and categorize interview data, with the aim of identifying key themes related to educational theory and rural environmental governance. This approach not only provided a comprehensive grasp of participants’ perspectives and cognitive processes but also established an evidence-based framework for policy recommendations. Specifically, it examined how green technology adoption influences educational outcomes in rural contexts.

Research ethics

We conducted our study with strict ethical guidelines in mind. Before starting the interviews, every participant signed an informed consent form that clearly explained the study’s purpose, what would happen during the process, and how their privacy would be protected. We promised to keep all interview data strictly for this project—no sharing with other studies—and removed any personal identifiers from the information.

If anyone felt uncomfortable during the interviews, they could stop participating anytime. These steps aren’t just about following rules; they’re about respecting people’s rights and building trust. By creating a safe and supportive environment, we’re not only protecting participants but also ensuring our findings are trustworthy and meaningful.

Results

Research of the impact of education on environmental awareness and behavioral regulation

Education improves rural residents’ awareness of environmental protection

The study’s findings stress the importance of education in improving environmental awareness in rural areas, with education serving as a powerful catalyst for positive behavioral changes. The majority of interviewees believe that environmental education projects such as school-based classes, community outreach programs, and government-sponsored environmental efforts have contributed to raising rural inhabitants’ awareness of the necessity of environmental protection. Most elementary and secondary school teachers agreed that one of the most significant advantages of environmental education was improved student understanding of the environmental impact of their daily behaviors. Students learned this through classes on environmental science, pollution, and ecological balance. Teacher E has noticed that younger generations are becoming more conscious of plastic waste. Many students have taken it upon themselves to stop using disposable plastic bags. They are also encouraging their friends and families to do the same. This collective effort highlights the powerful, long-lasting impact that education can have in promoting environmental responsibility.

These findings align with broader observations about the effectiveness of government and community-based education programs. As Environmentalist C noted,

“We have organized lectures and demonstration projects so peasants might observe firsthand the environmental consequences of agricultural pollution.”

The growing awareness of these issues has prompted peasants to take practical steps to reduce their use of harmful pesticides and fertilizers, which helps preserve soil and water quality. This shift not only improves environmental conditions but also has economic benefits, as highlighted by Environmentalist D:

“We demonstrated to the peasants how reducing fertilizer use not only protects the soil and water but also results in significant cost savings.”

These examples show how recognizing environmental issues raises people’s awareness and encourages them to make smaller, more ecologically responsible decisions every day. Furthermore, these statements are consistent with a broader conceptual framework of sustainable agriculture, which allows for both economic and environmental benefits. The practice of using less fertilizer aligns with the objectives of sustainable development38, which encourages practices that are both economically and environmentally sound. According to theory, this technique is based on win-win solutions in environmental economics39, in which efforts to reduce environmental harm offer economic rewards that improve the overall sustainability of agricultural practices.

Moreover, this approach may be interpreted through the perspective of behavioral economics, namely Nudge Theory40, which proposes that small changes in economic incentives, such as saving money, may have a big impact on decision-making. Environmentalists promote sustainable behavior by demonstrating to peasants the real financial benefits of reduced fertilizer use. This is consistent with the larger concept of cost-benefit analysis, which assesses the net economic and environmental impact of decisions, proving that adopting sustainable practices such as lowering fertilizer usage may result in both financial savings and environmental benefits.

However, while the study clearly shows the benefits of environmental education, it also indicates significant shortcomings. The content and organization of current environmental education programs should be enhanced. Many stakeholders, including environmental educators and practitioners, have emphasized that present curricula frequently prioritize theoretical understanding above real environmental challenges faced by rural populations. Plus, much of the educational content is urban-focused, with few examples of environmental problems unique to rural areas. As Village Leader D pointed out,

“The educational content does not address practical difficulties, such as our village’s poor wastewater treatment.”

This observation indicates a need for a more contextually relevant curriculum that directly addresses the real-world environmental challenges faced by rural populations.

Many peasants experience economic constraints, which are an important cause of opposition. Those who rely primarily on conventional agriculture show worries about adopting new, environmentally friendly methods, particularly when the initial costs are believed to be important. For example, many peasants see the benefits of adopting environmentally friendly approaches such as organic farming; however, the change necessitates an initial investment in new agricultural techniques, crops, and pest management practices that they cannot afford. Peasant C shared his thoughts, saying,

“I want to switch to organic farming, but right now, I can hardly manage my expenses. I can’t justify spending more money on something that might not show immediate results.”

This statement reflects the hesitation many peasants feel about investing in sustainable practices when their financial survival is at risk. These findings support research hypotheses 1 and 3.

The combined effects of rural conditions and educational materials

While education has helped to raise environmental consciousness in rural communities, the study also finds major gaps in the tools and materials available for effective teaching. Several respondents stated that the educational resources currently in use do not address the unique environmental concerns that rural inhabitants face. In particular, these guides do not offer practical advice on how to lessen the environmental impact of farming activities. Many peasants, for example, expressed a need for more specialized knowledge on themes such as water resource management, pesticide and fertilizer long-term viability and agricultural harvesting procedures that cause the least amount of environmental damage.

Many teachers, too, discovered a gap between the urban-focused examples in textbooks and the realities of rural residing. Teacher E pointed out that

“The case studies and examples in textbooks often focus on urban issues, such as waste sorting and green public transport, which are not relevant to our students who live in rural areas.”

The gap between the content of educational materials and rural inhabitants’ actual experiences leads to a mismatch between environmental knowledge and its practical use.

The gap between awareness and action is especially noticeable in rural communities. Although educational programs have successfully raised awareness about environmental conservation, many participants still feel frustrated because they struggle to apply this knowledge in real life. For instance, Environmentalist A pointed out that

“Villagers understand the importance of environmental conservation, but they often lack the practical skills needed to put this knowledge into action.”

A good example of this is that many villagers know the importance of reducing plastic waste, yet they don’t know how to make simple changes, like switching from plastic bags to reusable cloth bags. These everyday barriers highlight the need for more hands-on support to help people apply what they’ve learned about the environment.

When looking at the differences within groups, the study showed that younger and older peasants approach environmental education and sustainability initiatives in very different ways. Younger peasants tend to be more interested in new ways of learning, like online courses and workshops that teach innovative farming techniques and sustainability practices. For instance, a group of young peasants recently organized an online seminar where experts discussed the benefits of cover cropping and crop rotation as sustainable methods. Their enthusiasm for using technology to learn and apply modern farming practices is very different from the more conventional views of older peasants. The older generation tends to prefer in-person workshops and hands-on demonstrations that align with their long-standing farming methods. They often rely on practices they’ve used for years and are sometimes hesitant to adopt new techniques unless they can see clear, long-term benefits. This means that understanding these differences between generations and finding ways to bridge them is crucial for getting everyone in the community involved in environmental protection.

Additionally, some rural residents, including Peasant D, stressed the need for clearer guidance on sustainable agricultural practices. D mentioned,

“We understand the concept of organic farming and its benefits for the environment, but we lack a deeper understanding of how to put it into practice.”

This knowledge gap prevents peasants from shifting to more sustainable methods, causing them to stick with conventional chemical fertilizers and pesticides. D added,

“We would love to learn about organic farming if someone could explain its principles to us—we are eager to give it a try!”

This enthusiasm to learn shows the untapped potential of education to promote sustainable practices in rural areas, especially if educational content is customized to address the specific needs and challenges of rural life. These findings reinforce research hypothesis 2.

Relationship between education and green technology use

Education as a tool to promote green technology

The analysis of the questions stresses the significance of education as an important aspect in the promotion of environmentally friendly technologies. Education greatly improves rural populations’ competence and readiness to embrace and use green technology while also sharing important knowledge through instruction and demonstration. Participants pointed out that education is critical for accelerating the adoption of green technologies. Despite beginning with reluctance, several peasants stated that effective education helped them develop a true grasp of technologies. This insight helped them to see the technologies’ dual benefits: environmental preservation and profits.

Many peasants initially viewed technologies like solar energy systems and organic matter management as too expensive and complicated. However, educational initiatives have changed this perspective. They help peasants realize that these technologies protect the environment and bring real economic benefits. Education is key to reducing the hesitation of rural residents to adopt new technology and boosting their enthusiasm for promoting environmentally sustainable practices, including organic farming, water-efficient irrigation methods, and solar power systems.

Through successful demonstrations and clear explanations of solar water heaters, experts effectively showed community members how these technologies could significantly lower energy costs while benefiting the environment. As Village Leader D noted,

“The villagers have gradually adopted these sustainable technologies, and a significant number of families chose to install solar water heaters.� This shift highlights how education serves as a tool for spreading knowledge, encouraging the acceptance and use of green technologies in rural areas. These findings support research hypothesis 2.

Understanding and embracing green technology across various demographics

The data showed significantly different views and acceptance levels of eco-friendly technologies among various demographic groups. People involved in education and environmental action often have a deep understanding of green technology and its role in conserving natural resources. Educators play a crucial role in raising children’s awareness of environmental issues. They introduce sustainable technologies and help students grasp these important concepts.

Take Teacher D, for instance. She explained how her classroom uses green technologies like solar panels and rainwater harvesting systems to show practical solutions to environmental challenges. The students were incredibly excited as they participated in a rainwater harvesting project in the school garden. This hands-on experience enhanced their theoretical learning. By educating young people about the importance of environmental conservation, we are building a strong foundation for sustainable practices in their future.

The analysis revealed a strong economically motivated mindset among many peasants. For older generations, adopting new green technologies often focuses on immediate financial returns instead of long-term ecological benefits. Peasant D expressed this viewpoint clearly:

“If the new technology does not lead to cost savings or increased income, we prefer to continue using conventional methods.”

This attitude shows a key reason for resistance to adopting green technologies. Many peasants prioritize short-term economic gains over potential long-term environmental advantages.

In contrast, younger farmers generally have a more open mindset toward education. They are eager to explore innovative technologies that can improve their farming practices. Take, for instance, the workshops organized by some younger farmers that focus on soil health and sustainable practices. This shows their proactive attitude toward integrating green technologies into their operations. Their approach indicates a willingness to invest in education and experimentation. Older farmers might resist these changes due to financial concerns.

The differences in attitudes highlight the need for tailored educational strategies. We can improve understanding by providing practical examples and clear evidence of the economic benefits linked to green technology. Teacher B emphasized this point when she said,

“For farmers to fully adopt green technology, there must be visible evidence of both improved environmental conditions and increased income.”

By aligning educational content with the economic realities that farmers face, we can help promote greater acceptance of sustainable practices.

Additionally, the role of village leaders is crucial in encouraging the adoption of green technologies. When community leaders actively support new practices, farmers become more willing to engage. Peasant A pointed out this importance:

“The village chief of our community is very supportive of green technologies. He not only organized several lectures on environmentally friendly farming, but he also took us to demonstration plots using these technologies.”

This kind of leadership creates a collaborative environment where community members feel motivated to adopt sustainable practices.

In conclusion, the different perspectives among demographic groups and the financially driven mindset of older farmers play a significant role in adopting green technologies. We need educational initiatives that acknowledge these differences and present clear economic reasons to support change. Such strategies will help create an environment that promotes sustainable practices. They directly tackle the challenges of managing rural environments while highlighting the essential role education plays in increasing the adoption of green technology. These findings back research hypothesis 3.

Challenges in combining education and environmental management

Limited access to educational resources and expansion challenges

The findings of this study show that limited access to educational resources is a major barrier to effective environmental management in rural areas. Many educators and environmental practitioners have pointed out that the uneven distribution of resources makes it difficult to provide adequate teaching materials, teacher training, and educational equipment in remote locations. This lack of resources significantly affects the quality and accessibility of environmental education. As a result, it also impacts environmental awareness and the willingness of rural residents to change their behaviors.

Teacher A raised an important concern, saying,

“It is challenging to ensure the effectiveness of education because we rarely have the chance to attend professional training on environmental education. We often have to rely on ourselves to find materials.”

Environmental practitioners also noted that low financial support often limits program execution. Environmentalist E mentioned,

“We face the problem of insufficient funding, which directly impacts the effectiveness of our outreach efforts. Take, for instance, our desire to organize activities that raise public awareness of environmental issues. We want to do this, but we lack the resources to create informative materials or hire experts for presentations”.

This shortage of funding ultimately reduces community interest in participating in educational programs.

The nature of environmental education makes engagement more difficult. Much of the current teaching uses a one-way transmission model. This approach does not actively involve participants. Peasant A expressed this concern, saying,

“Environmental education classes feel like the teacher is talking at us while we listen. It gets a bit boring. If we could plant trees or clean up our rivers, we would be more interested and better understand the importance of protecting the environment.”

This highlights the need for hands-on, participatory educational experiences that truly connect with community members.

Additionally, the complexity of green technology rules and processes creates barriers for farmers in understanding and applying these technologies. Environmentalist C pointed out,

“Even though we’ve seen solar and wind technologies promoted in some areas for several years, many farmers still don’t fully understand how to implement them because they are quite complicated.”

There is a clear need for more training and hands-on experience to help farmers adopt these energy-efficient and environmentally friendly technologies.

These challenges show that successful educational initiatives in rural environmental management require better resource distribution and a more focused approach to developing educational materials. By addressing these specific needs, educational institutions can improve rural residents’ understanding and engagement in sustainable practices. These findings support research hypothesis 2.

Low farmer participation and financial difficulties

The study also highlighted low levels of participation among farmers as a major barrier to effective environmental management in rural areas. Many village leaders and farmers pointed out that low motivation comes from several factors. These include a lack of understanding of environmental issues, skepticism about the effectiveness of green technology, and concerns about the high upfront costs of adopting new technologies. Village Leader E noted,

Many farmers think that environmental conservation and green technology promotion are the government’s responsibility and not relevant to their personal lives.

This perspective creates a sense of disengagement and discourages active participation in educational programs focused on environmental management.

Cost continues to be a major barrier to adopting green technologies. Innovations like solar energy systems and water-saving irrigation methods can reduce resource consumption and pollution in the long run, but they often require a significant initial investment. Peasant E described this challenge:

“For those of us who grow food, we choose methods that save money and are effective. While we know that conventional practices may harm the environment, we need to focus on our livelihoods.”

This perspective shows how financial pressures can prevent farmers from adopting environmentally friendly practices, as they prioritize their immediate economic needs over long-term ecological benefits.

Integrating insights about generational differences within farming communities adds depth to this analysis. Younger farmers often show more openness to learning about new technologies and practices, while older farmers may stick to conventional methods. For instance, a younger farmer might eagerly participate in training sessions focused on organic practices because they see potential for future profit. In contrast, an older farmer might prioritize the immediate economic impact of new investments. This generational divide underscores the need for targeted educational strategies that address the specific motivations and barriers that different age groups face.

The research revealed that successfully distributing and adopting green technology often relies on government support, technical assistance, and comprehensive training. In some regions, the government provided not only seeds and technical training but also market services to promote organic agriculture, which led to greater farmer engagement. Village Leader C shared a successful example, stating,

“To promote organic rice, we not only supplied farmers with free organic fertilizer but also invited experts for hands-on guidance”.

This supportive approach effectively encouraged many farmers to try organic farming practices while enjoying positive market returns.

These observations highlight a crucial point: integrating education and environmental management requires a deeper, multi-faceted level of support that goes beyond isolated educational activities. By investing in comprehensive educational frameworks that offer tailored resources and address economic concerns, we can create a more supportive environment for adopting green technologies. These findings support research hypotheses 1, 2, and 3.

Discussion

This study investigates how educational science may help rural communities in overcoming socioeconomic issues, improving environmental management, and increasing adoption of environmental technologies. It also aims to raise environmental awareness among rural populations. Various socioeconomic issues frequently hinder rural communities’ sustainable growth and good environmental management. These challenges include inadequate financial resources, a lack of technical access, insufficient policy support, and poor information exchange. As a result, rural communities struggle to control their own environment. These concerns also reduce their willingness to accept and implement innovative environmental technologies. Given these issues, it is evident that increasing environmental awareness in rural regions is necessary. Strengthening residents’ abilities to handle environmental issues through educational science is significant. This method is critical for promoting sustainable development in rural communities.

Education plays an important role in sharing knowledge and developing skills, which helps to reduce the influence of socioeconomic obstacles on environmental governance. On the one hand, education enables rural populations to better comprehend environmental challenges, raise awareness, and adopt appropriate environmental management practices. Education improves understanding of environmental problems by sharing knowledge and giving training. For example, while adopting environmental protection technologies, education may show communities how to use them, explain the environmental benefits, and emphasize potential financial gains. This strategy may contribute to reducing resistance, which is typically caused by a lack of information or misunderstandings. On the other hand, education improves relationships and promotes collaboration in rural areas. School programs and community workshops might promote information sharing and teamwork, changing environmental initiatives from one-time actions into long-term, collaborative solutions for sustainable development. Education not only helps people improve their skills, but it also helps them build stronger social networks. This promotes the adoption of innovative technology and the effective execution of environmental legislation in rural areas.

The socioeconomic status of rural residents has a significant impact on the success of environmental education41. Financial pressures frequently lead some rural residents to focus more on short-term economic gains and less on the long-term importance of environmental protection. This mindset may influence how they perceive environmental education. When learning about new technologies, they are often more interested in whether these technologies offer quick profits. Consider low-carbon farming methods, for example. Farmers may be more focused on short-term crop production adjustments than on long-term benefits such as soil health and ecosystem restoration. A comprehensive approach is required to increase the effectiveness of rural environmental education. This should include improved teacher training, updated curriculum, and a link between education and financial rewards. These actions may encourage residents to take action and protect the environment in ways that improve both their short- and long-term well-being.

Given the many challenges in rural environmental education, relying solely on traditional classroom teaching is unlikely to bring about lasting environmental behavior change. Therefore, it is crucial to promote reforms in social and ecological education to build a comprehensive and long-term system for rural environmental education.

Integrating environmental education into the government’s rural education system is essential for building environmental awareness and promoting sustainable practices in rural communities. This integration helps improve environmental attitudes, values, and knowledge. It also prepares individuals and communities to take positive actions toward protecting the environment42. This needs both the government and educational institutions to prioritize environmental issues in primary and secondary school curricula. This makes environmental education an essential component of students’ entire development. In terms of specific subjects, topics like environmental management, ecological protection, and sustainable farming could be added to the science curriculum. Additionally, practical activities and case studies could be included to help students develop problem-solving and hands-on skills. These changes would ensure that students not only learn about the environment but also gain the tools they need to address real-world environmental challenges.

Environmental education reform ought to focus on a broader approach that addresses rural communities’ economic and social concerns. Environmental information might be included in agricultural training for practical application purposes. It might enable farmers to learn not only how to enhance crop yields but also how to use sustainable farming methods. Additionally, vocational training might include eco-tourism and circular economy ideas. These programs aim to provide rural residents with essential skills, opening up new job prospects in sustainable industries. By tying education to community needs, we may ensure that environmental education helps both environmental protection and local economic development.

Finally, in order to build a sustainable and successful learning environment, governments, communities, and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) need to work together. The government may play an important role by implementing policies that provide reward43. In terms of rewards, green production subsidies and low-carbon agriculture certifications may encourage farmers to use environmentally friendly technologies. Community organizations might create platforms for sharing environmental knowledge, helping residents to stay informed and connected. Non-governmental organizations (NGOs) may also offer their skills to help rural communities establish better sustainability policies. Working together, these organizations may assist ensure that environmental education results in real, long-term changes.

The present analysis confirms several previous discoveries while broadening their scope and comprehensiveness. Extensive research has shown that education has a vital role in environmental preservation by enhancing residents’ environmental consciousness and promoting eco-friendly actions44. According to Hasan et al.’s research, education about the environment may raise awareness and promote greater environmental care while also slowing urban growth and accelerating rural development45. Hasan et al. showed that effective environmental education increases rural dwellers’ awareness of their vulnerability to environmental harm and motivates them to safeguard it. Such evidence substantiates the hypothesis of this study that education enhances the environmental consciousness of rural residents and motivates them to adopt sustainable lifestyles. Therefore, this study suggests that the localization and practicability of instructional materials are crucial factors in determining the impact of education. Thus, this discovery enriches literary discourse. A considerable amount of research has focused on the impact of education on environmental awareness on a broad scale, neglecting the alignment between educational material and the needs of educated populations. This study employs field interviews to demonstrate that current educational materials exhibit an excessive presence of urban elements and fail to address rural environmental concerns. The present study emphasizes the significance of localization and practicality in educational materials as means to enhance effectiveness. It also provides novel insights for environmental education planning and implementation.

Moreover, this study revealed major differences in the way different groups perceive and embrace green technology, thereby offering targeted suggestions for promoting green technology adoption. Prior studies have addressed the enhancement of the technology itself, including facilitating its use and reducing its cost46. However, these studies have overlooked the significance of education in reducing the barrier to adopting green technology. This study, based on a thorough investigation of attendees, demonstrates a connection between education and farmers’ engagement. Educational activities effectively persuade farmers to embrace novel technologies by demonstrating their economic advantages. After receiving instruction on solar PV systems, some farmers not only gained the knowledge to operate them but also developed a stronger desire to experiment with the new technology by comparing the cost of conventional energy with its advantages. These findings emphasize the critical role of education in the spread of green technologies47.

Moreover, Demetriou et al. view education as a tool for transmitting information, aiming to enhance knowledge and cognitive abilities48. Furthermore, this study demonstrates that education not only facilitates knowledge transfer but also enhances learners’ behavior by fostering interaction and engagement. We can enhance the acceptability and operational competence of green technology through practical demonstrations and interactive education. Rural environmental management communities typically acquire new technologies by direct experience and demonstration, underscoring the need for practical and engaging instructional methods. The present study specifically examines the practical obstacles encountered in the integration of education and environmental management, in contrast to previous research. While many studies have focused on education policies and resource allocation49,50, only a limited number have investigated grassroots issues such as insufficient resources, fragmented educational content, and low farmer involvement. These problems are intricate and varied, as evidenced by comprehensive interviews conducted with educators, community officials, and farmers. A lack of educational resources, including instructional materials, equipment, and teacher training and support, has a direct impact on education’s effectiveness51. Farmers’ level of knowledge and economic circumstances limit their views on environmental and green technology52. These findings further enhance the effectiveness of education and environmental management policies and supplement current studies.

Strengths, limitations, and future directions

This research stresses the role of education in rural environmental management and green technology promotion, with important theoretical and practical implications. The study examines the impact of education on improving environmental consciousness and promoting the use of green technologies by interview techniques and other measures. The study advocates localizing educational content, improving teacher training, and increasing economic incentives by examining various groups such as teachers, environmental practitioners, rural employees, and farmers, which provides scientific evidence for policy optimization. Additionally, the study closely harmonizes theory and practice, proving the real value of education in environmental conservation by examples and data analysis.

However, there are certain limitations on the study. The study’s findings have limitations in terms of national applicability because the interview sample is small and concentrated in central China’s rural areas. The findings’ objectivity and generalizability were further impacted by the subjective nature of the interviewing process and the absence of quantitative analysis. Furthermore, the study failed to fully investigate the long-term impacts of education on environmental behavior, limiting its potential for predicting the future.

Future research could prioritize examining how educational initiatives might assist rural populations in harmonizing development priorities while illuminating how environmental preservation and economic growth can mutually reinforce each other through localized case studies. Second, testing participatory approaches and collaborative decision-making mechanisms to encourage meaningful civic engagement in sustainability planning. Finally, investigating cost-effective green technology integration into curricula through contextually tailored pedagogies that align with rural poverty alleviation goals and foster ecologically sustainable livelihoods.

Conclusion

Rural communities may become more environmentally conscious, increase their use of green technology, and better manage their natural resources through education science. This study demonstrates the importance of education in rural environmental management and highlights the primary challenges and solutions through field interviews and comprehensive analysis. The research shows that classroom instruction, community outreach, and practical training significantly enhance the environmental understanding and protective behaviors of rural residents. Education improves rural communities’ understanding of the importance of environmental issues and motivates them to gradually implement ecological values and adopt more environmentally friendly behaviors53. Agricultural education has eased farmers’ resistance to new technologies and strengthened their willingness to adopt green technology through training and field exercises54.

The research reveals that rural environmental education faces widespread issues, including limited educational resources, low farmer participation, and high costs related to green technological alternatives. These considerations impose limitations on the possibilities. The report proposes prioritizing localized and practical educational content, as well as allocating revenue toward educational resources such as teacher training and instructional materials. Equipping farmers with financial rewards is crucial in order to motivate them to use environmentally friendly technology55. The study’s findings suggest that the field of education science has an important impact on rural environment management. In order to promote rural revitalization and dual-carbon programs, it is advisable to improve the integration of education and environmental management, distribute resources effectively, and apply rewards systems.

Data availability

Correspondence and requests for materials should be addressed to Chunlin Qi.

References

-

Joo, S. H. Evaluating the inequity impact of climate change on urban and rural communities. Prev. Treat. Nat. Disasters. 3 (1), 95–102 (2024).

-

Mihai, F. C. et al. Plastic pollution, waste management issues, and circular economy opportunities in rural communities. Sustainability 1, 20 (2021).

-

Carlsen, L. & Bruggemann, R. The 17 united nations’ sustainable development goals: A status by 2020. Int. J. Sustainable Dev. World Ecol. 29, 219–229 (2022).

-

Yu, G. et al. Discussion on action strategies of China’s carbon peak and carbon neutrality. Bull. Chin. Acad. Sci. [Chinese Version]. 37, 423–434 (2022).

-

Wei, W. et al. Dual carbon goals and the impact on future agricultural development in China: A general equilibrium analysis. China Agricultural Economic Rev. 14, 664–685 (2022).

-

Wals, A. E. J. et al. Convergence between Sci. Environ. Educ. Sci. 344 (6184), 583–584 (2014).

-

Fitri, D. E. N. Environmental education: is it a crucial factor in improving Pro-Environmental behavior among students?? Educ. Hum. Dev. J. 9 (1), 40–47 (2024).

-

Vasconcelos, C. & Orion, N. Earth science education as a key component of education for sustainability. Sustainability 13 (3), 1316 (2021).

-

Gómez Zermeño, M. G. & de la Alemán Garza, L. Y. Open laboratories for social innovation: A strategy for research and innovation in education for peace and sustainable development. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 22 (2), 344–362 (2021).

-

Devibar, M. H. & Green technology adoption puzzle: what can we learn from the field.Russian Law J. 11, 854–859 (2023).

-

Song, J. The impact of economic development on inadequate education resources in rural China. J. Educ. Humanit. Social Sci. 23, 285–290 (2023).

-

Ardoin, N. M., Bowers, A. W. & Gaillard, E. Environmental education outcomes for conservation: A systematic review. Biol. Conserv. 241, 108224 (2020).

-

Dimante, D., Tambovceva, T. & Atstaja, D. Raising environmental awareness through education. Int. J. Continuing Eng. Educ. Life Long. Learn. 26 (3), 259–272 (2016).

-

Ma, L., Shahbaz, P., Haq, S. U. & Boz, I. Exploring the moderating role of environmental education in promoting a clean environment. Sustainability 15 (10), 8127 (2023).

-

Su, Y. & Zhao, H. Infiltration approach of green environmental protection education in the view of sustainable development. Sustainability 15, 5287 (2023).

-

Lamanauskas, V. The importance of environmental education at an early age. J. Baltic Sci. Educ. 22, 564–567 (2023).

-

Yang, B. et al. Narrative-based environmental education improves environmental awareness and environmental attitudes in children aged 6–8. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 19, 6483 (2022).

-

Busi, R., Gandipilli, G. & Kuramana, S. Elements of environmental education, curriculum and teacher’s perspective: A review. Integr. J. Res. Arts Humanit. 3, 9–17 (2023).

-

Zhu, S. et al. Export structures, income inequality, and urban-rural divide in China. Appl. Geogr. 115, 102150 (2020).

-

Hoffmann, R. & Muttarak, R. Greening through schooling: understanding the link between education and pro-environmental behavior in the Philippines. Environ. Res. Lett. 15, 014009 (2020).

-

Uvarova, I. et al. Development of the green entrepreneurial mindset through modern entrepreneurship education. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science. 628, 012034 (2021).

-

Crawford, J. & Cifuentes-Faura, J. Sustainability in higher education during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review. Sustainability 14, 1879 (2022).

-

Xiuling, D. et al. The impact of technical training on farmers adopting water-saving irrigation technology: an empirical evidence from China. Agriculture 13, 956 (2023).

-

Hsu, C. C. et al. Evaluating green innovation and performance of financial development: mediating concerns of environmental regulation. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 28, 57386–57397 (2021).

-

Yang, P. et al. Review on drip irrigation: impact on crop yield, quality, and water productivity in China. Water 15, 1733 (2023).

-

Pan, W. & Mei, H. A design strategy for energy-efficient rural houses in severe cold regions. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 17, 6481 (2020).

-

Ahmad, G. E. Photovoltaic-powered rural zone family house in Egypt. Renew. Energy. 26, 379–390 (2002).

-

Shahsavari, A. & Akbari, M. Potential of solar energy in developing countries for reducing energy-related emissions. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 90, 275–291 (2018).

-

Tahat, M. et al. Soil health and sustainable agriculture. Sustainability 12, 4859 (2020).

-

Wan, N. F. et al. Ecological intensification of rice production through rice-fish co-culture. J. Clean. Prod. 234, 1002–1012 (2019).

-

Sipayung, R. et al. Utilization of agricultural waste from Brebeg Cilacap village to become biogas using cow manure. Fluida 16, 1–10 (2023).

-

Deep, G. Exploring the role and impact of green technology in building a sustainable future. Int. J. Sci. Technol. Res. Archive. 5, 128–133 (2023).

-

Trapp, C. T. C. & Kanbach, D. K. Green entrepreneurship and business models: deriving green technology business model archetypes. J. Clean. Prod. 297, 126694 (2021).

-

Deshuai, M., Hui, L. & Ullah, S. Pro-environmental behavior–renewable energy transitions nexus: exploring the role of higher education and information and communications technology diffusion. Front. Psychol. 13, 1010627 (2022).

-

Luo, L. et al. Research on the influence of education of farmers’ cooperatives on the adoption of green prevention and control technologies by members: evidence from rural China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 19, 6255 (2022).

-

Ma, J. & Jin, H. Increasing sustainability literacy for environmental design students: A transdisciplinary learning practice. Sustainability 14, 12379 (2022).

-

Li, X. et al. The role of education and green innovation in green transition: advancing the united nations agenda on sustainable development. Sustainability 15, 12410 (2023).

-

Goodland, R. & Ledec, G. Neoclassical economics and principles of sustainable development. Ecol. Model. 38 (1–2), 19–46 (1987).

-

Muradian, R. et al. Payments for ecosystem services and the fatal attraction of win-win solutions. Conserv. Lett. 6 (4), 274–279 (2013).

-

Cai, C. W. Nudging the financial market? A review of the nudge theory. Acc. Finance. 60 (4), 3341–3365 (2020).

-

Cheng, H. & Mao, C. Disparities in environmental behavior from Urban–rural perspectives: how socioeconomic status structures influence residents’ environmental actions—based on the 2021 China general social survey data. Sustainability.16(18), 7886 (2024).

-

Ardoin, N. M., Bowers, A. W. & Gaillard, E. Environmental education outcomes for conservation: A systematic review. Biol. Conserv.. 241, 108224 (2020).

-

Li, Z., Pan, Y., Yang, W., Ma, J. & Zhou, M. Effects of government subsidies on green technology investment and green marketing coordination of supply chain under the cap-and-trade mechanism. Energy Econ. 101, 105426 (2021).

-

Schneiderhan-Opel, J. & Bogner, F. X. Cannot see the forest for the trees? Comparing learning outcomes of a field trip vs. a classroom approach. Forests 12, 1265 (2021).

-

Hasan, H. A. et al. Mapping the environmental education policies for the youth to encourage rural development and to reduce urbanisation: econometric approach. J. Environ. Assess. Policy Manage. 25, 2350013 (2023).

-

Caldeira, K., Duan, L. & Moreno-Cruz, J. The value of reducing the green premium: cost-saving innovation, emissions abatement, and climate goals. Environ. Res. Lett. 18, 104051 (2023).

-

Husaini, Q. M., Ruswandi, U., Erihadiana, M., Sustainable development as & the basis for environmental education in developing green schools. Ilmuna: Jurnal Studi Pendidikan Agama Islam 5, 92–111 (2023).

-

Demetriou, A. et al. Cognitive ability, cognitive self-awareness, and school performance: from childhood to adolescence. Intelligence 79, 101432 (2020).

-

Liu, C. et al. Research on regional differences and influencing factors of green technology innovation efficiency of China’s high-tech industry. J. Comput. Appl. Math. 369, 112597 (2020).

-

Tong, L. et al. Role of environmental regulations, green finance, and investment in green technologies in green total factor productivity: empirical evidence from Asian region. J. Clean. Prod. 380, 134930 (2022).

-

Liu, J. et al. The relation between family socioeconomic status and academic achievement in China: A meta-analysis. Edu. Psychol. Rev. 32, 49–76 (2020).

-

Hannus, V. & Sauer, J. Understanding farmers’ intention to use a sustainability standard: the role of economic rewards, knowledge, and ease of use. Sustainability 13, 10788 (2021).

-

Eliades, F. et al. Carving out a niche in the sustainability confluence for environmental education centers in Cyprus and Greece. Sustainability 14, 8368 (2022).

-

Wang, X. et al. How channels of knowledge acquisition affect farmers’ adoption of green agricultural technologies: evidence from Hubei Province, China. Int. J. Agric. Sustain. 21, 2270254 (2023).

-

Meng, F. et al. What drives farmers to participate in rural environmental governance? Evidence from villages in Sandu town, Eastern China. Sustainability 14, 3394 (2022).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

ChunLin Qi wrote the main manuscript text . All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

The studies involving human participants were approved by the faculty of education at HeNan Normal University. Written informed consent to participate in this study was provided by the participants.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Qi, C. The role of educational science in environmental management and green technology adoption in rural revitalization through interview-based insights.

Sci Rep 15, 19544 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-95791-4

-

Received: 04 November 2024

-

Accepted: 24 March 2025

-

Published: 04 June 2025

-

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-95791-4

Keywords

Search

RECENT PRESS RELEASES

Related Post