The rise of green tech is feeding another environmental crisis

July 20, 2025

How the rise of green tech is feeding another environmental crisis

BBC

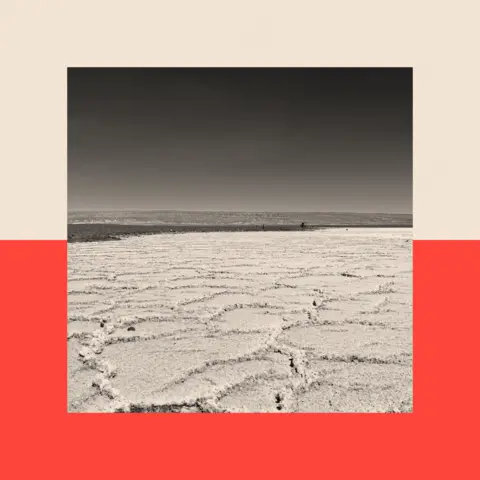

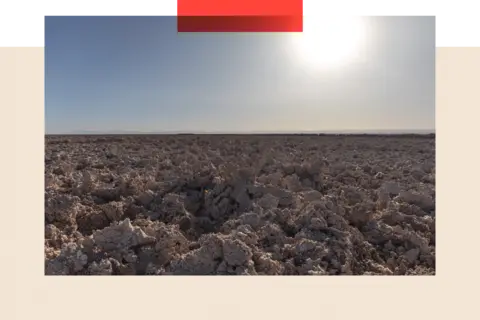

BBCRaquel Celina Rodriguez watches her step as she walks across the Vega de Tilopozo in Chile’s Atacama salt flats.

It’s a wetland, known for its groundwater springs, but the plain is now dry and cracked with holes she explains were once pools.

“Before, the Vega was all green,” she says. “You couldn’t see the animals through the grass. Now everything is dry.” She gestures to some grazing llamas.

For generations, her family raised sheep here. As the climate changed, and rain stopped falling, less grass made that much harder.

But it worsened when “they” started taking the water, she explains.

Ben Derico/BBC

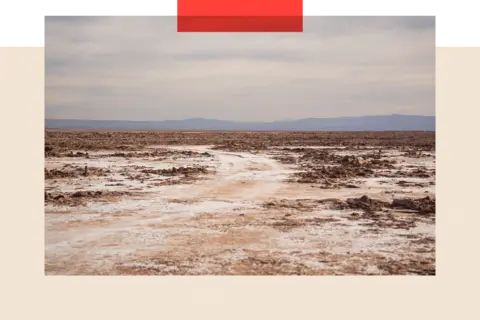

Ben Derico/BBC“They” are lithium companies. Beneath the salt flats of the Atacama Desert lie the world’s largest reserves of lithium, a soft, silvery-white metal that is an essential component of the batteries that power electric cars, laptops and solar energy storage.

As the world transitions to more renewable energy sources, the demand for it has soared.

In 2021, about 95,000 tonnes of lithium was consumed globally – by 2024 it had more than doubled to 205,000 tonnes, according to the International Energy Agency (IEA).

By 2040 it’s predicted to rise to more than 900,000 tonnes.

Most of the increase will be driven by demand for electric car batteries, the IEA says.

Locals say environmental costs to them have risen too.

So, this soaring demand has raised the question: is the world’s race to decarbonise unintentionally stoking another environmental problem?

Flora, flamingos and shrinking lagoons

Chile is the second-largest producer of lithium globally after Australia. In 2023, the government launched a National Lithium Strategy to ramp up production through partly nationalising the industry and encouraging private investment.

Its finance minister previously said the increase in production could be by up to 70% by 2030, although the mining ministry says no target has been set.

This year, a major milestone to that is set to be reached.

Ben Derico/BBC

Ben Derico/BBCA planned joint enterprise between SQM and Chile’s state mining company Codelco has just secured regulatory approval for a quota to extract at least 2.5 million metric tonnes of lithium metal equivalent per year and boost production until 2060.

Chile’s government has framed the plans as part of the global fight against climate change and a source of state income.

Mining companies predominantly extract lithium by pumping brine from beneath Chile’s salt flats to evaporation pools on the surface.

The process extracts vast amounts of water in this already drought-prone region.

Ben Derico/BBC

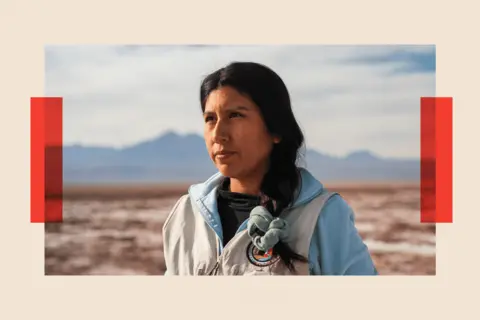

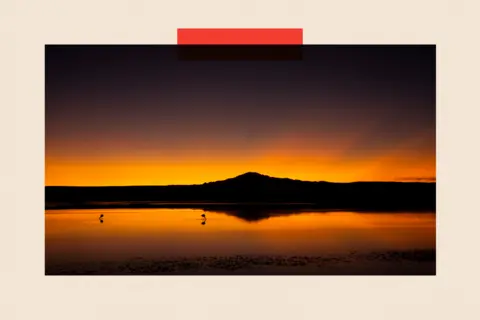

Ben Derico/BBCFaviola Gonzalez is a biologist from the local indigenous community working in the Los Flamencos National Reserve, in the middle of the Atacama Desert, home to vast salt flats, marshes and lagoons and some 185 species of birds. She has monitored how the local environment is changing.

“The lagoons here are smaller now,” she says. “We’ve seen a decrease in the reproduction of flamingos.”

She said lithium mining impacts microorganisms that birds feed on in these waters, so the whole food chain is affected.

She points to a spot where, for the first time in 14 years, flamingo chicks hatched this year. She attributes the “small reproductive success” to a slight reduction in water extraction in 2021, but says, “It’s small.”

“Before there were many. Now, only a few.”

The underground water from the Andes, rich in minerals, is “very old” and replenishes slowly.

“If we are extracting a lot of water and little is entering, there is little to recharge the Salar de Atacama,” she explains.

Lucas Aguayo Araos/Anadolu Agency via Getty Images

Lucas Aguayo Araos/Anadolu Agency via Getty ImagesDamage to flora has also been found in some areas. On property in the salt flats, mined by the Chilean company SQM, almost one-third of the native “algarrobo” (or carob) trees had started dying as early as 2013 due to the impacts of mining, according to a report published in 2022 by the US-based National Resources Defense Council.

But the issue extends beyond Chile too. In a report for the US-based National Resources Defense Council in 2022, James J. A. Blair, an assistant professor at California State Polytechnic University, wrote that lithium mining is “contributing to conditions of ecological exhaustion”, and “may decrease freshwater availability for flora and fauna as well as humans”.

He did, however, say that it is difficult to find “definitive” evidence on this topic.

Mitigating the damage

Environmental damage is of course inevitable when it comes to mining. “It’s hard to imagine any kind of mining that does not have a negative impact,” says Karen Smith Stegen, a political science professor in Germany, who studies the impacts of lithium mining across the world.

The issue is that mining companies can take steps to mitigate that damage. “What [mining companies] should have done from the very beginning was to involve these communities,” she says.

For example, before pumping lithium from underground, companies could carry out “social impact assessments” – reviews which take into account the broad impact their work will have on water, wildlife, and communities.

Getty Images

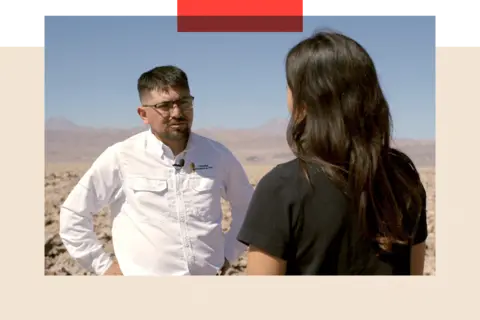

Getty ImagesFor their part, mining companies now say they are listening. The Chilean firm SQM is one of the main players.

At one of their plants in Antofagasta, Valentín Barrera, Deputy Manager of Sustainability at SQM Lithium, says the firm is working closely with communities to “understand their concerns” and carrying out environmental impact assessments.

He feels strongly that in Chile and globally “we need more lithium for the energy transition.”

He adds that the firm is piloting new technologies. If successful, the idea is to roll these out in their Salar de Atacama plants.

These include both extracting lithium directly from brine, without evaporation pools, and technologies to capture evaporated water and re-inject it into the land.

“We are doing several pilots to understand which one works better in order to increase production but reduce at least 50% of the current brine extraction,” he said.

Ben Derico/BBC

Ben Derico/BBCHe says the pilot in Antofagasta has recovered “more than one million cubic metres” of water. “Starting in 2031, we are going to start this transition.”

But the locals I spoke to are sceptical. “We believe the Salar de Atacama is like an experiment,” Faviola argues.

She says it’s unknown how the salt flats could “resist” this new technology and the reinjection of water and fears they are being used as a “natural laboratory.”

Sara Plaza, whose family also raised animals in the same community as Raquel, is anxious about the changes she has seen in her lifetime.

She remembers water levels dropping from as early as 2005 but says “the mining companies never stopped extracting.”

Ben Derico/BBC

Ben Derico/BBCSara becomes tearful when she speaks about the future.

“The salt flats produce lithium, but one day it will end. Mining will end. And what are the people here going to do? Without water, without agriculture. What are they going to live on?”

“Maybe I won’t see it because of my age, but our children, our grandchildren will.”

She believes mining companies have extracted too much water from an ecosystem already struggling from climate change.

“It’s very painful,” she adds. “The companies give the community a little money, but I’d prefer no money.

“I’d prefer to live off nature and have water to live.”

The impact of water shortages

Sergio Cubillos is head of the association for the Peine community, where Sara and Raquel live.

He says Peine has been forced to change “our entire drinking water system, electrical system, water treatment system” because of water shortages.

“There is the issue of climate change, that it doesn’t rain anymore, but the main impact has been caused by extractive mining,” he says.

He says since it started in the 1980s, companies have extracted millions of cubic metres of water and brine – hundreds of litres per second.

“Decisions are made in Santiago, in the capital, very far from here,” he says.

Lucas Aguayo Araos/Anadolu via Getty Images

Lucas Aguayo Araos/Anadolu via Getty ImagesHe believes that if the President wants to fight climate change, like he said when he ran for office, he needs to involve “the indigenous people who have existed for millennia in these landscapes.”

Sergio understands that lithium is very important for transitioning to renewable energy but says his community should not be the “bargaining chip” in these developments.

His community has secured some economic benefits and oversight with companies but is worried about plans to ramp up production.

He says while seeking technologies to reduce the impact on water is welcome that “can’t be done sitting at a desk in Santiago, but rather here in the territory.”

Ben Derico/BBC

Ben Derico/BBCChile’s government stresses there has been “ongoing dialogue with indigenous communities” and they have been consulted over the new Codelco-SQM joint venture’s contracts to address concerns around water issues, new technologies and contributions to the communities.

It says increasing production capacity will be based on incorporating new technologies to minimise the environmental and social impact and that the high “value” of lithium due to its role in the global energy transition could provide “opportunities” for the country’s economic development.

Sergio though worries about their area being a “pilot project” and says if the impact of new technology is negative, “We will put all our strength into stopping the activity that could end with Peine being forgotten.”

A small part of a global dilemma

The Salar de Atacama is a case study for a global dilemma. Climate change is causing droughts and weather changes. But one of the world’s current solutions is – according to locals – exacerbating this.

There is a common argument from people who support lithium mining: that even if it damages the environment, it brings huge benefits via jobs and cash.

Daniel Jimenez, from lithium consultancy iLiMarkets, in Santiago, takes this argument a step further.

He claims that environmental damage has been exaggerated by communities who want a pay-out.

Lucas Aguayo Araos/Anadolu Agency via Getty Images

Lucas Aguayo Araos/Anadolu Agency via Getty Images“This is about money,” he argues. “Companies have poured a lot of money into improving roads, schools – but the claims of communities really go back to the fact they want money.”

But Prof Stegen is unconvinced. “Mining companies always like to say, ‘There are more jobs, you’re going to get more money’,” she says.

“Well, that’s not particularly what a lot of indigenous communities want. It actually can be disruptive if it changes the structure of their own traditional economy [and] it affects their housing costs.

“The jobs are not the be all and end all for what these communities want.”

Ben Derico/BBC

Ben Derico/BBCIn Chile, those I spoke to didn’t talk about wanting more money. Nor are they opposed to measures to tackle climate change. Their main question is why they are paying the price.

“I think for the cities maybe lithium is good,” Raquel says. “But it also harms us. We don’t live the life we used to live here.”

Faviola does not think electrifying alone is the solution to climate change.

“We all must reduce our emissions,” she says. “In developed countries like the US and Europe the energy expenditure of people is much greater than here in South America, among us indigenous people.”

“Who are the electric cars going to be for? Europeans, Americans, not us. Our carbon footprint is much smaller.”

“But it’s our water that’s being taken. Our sacred birds that are disappearing.”

Top image credit: Getty Images

BBC InDepth is the home on the website and app for the best analysis, with fresh perspectives that challenge assumptions and deep reporting on the biggest issues of the day. And we showcase thought-provoking content from across BBC Sounds and iPlayer too. You can send us your feedback on the InDepth section by clicking on the button below.

Search

RECENT PRESS RELEASES

Related Post