Is climate change affecting hummingbirds? Researchers are trying to find out

September 18, 2025

RALEIGH, N.C. — With the start of fall only days away, some hummingbirds are still migrating south to Mexico and Central America.

While the majority of hummingbirds begin their flight south by October, you still may see some of the tiny birds around North Carolina in the coming weeks.

These birds travel great lengths every year. To learn more about their migrations and habits, the North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences has been working with researchers over the past 20 years to capture, band and release hummingbirds.

What You Need To Know

The North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences has been working on its hummingbird banding project for decades

Hummingbirds travel hundreds of miles during their migration

Susan Campbell, one of the researchers working on this project, says banding does not hurt the birds

You can help track hummingbirds in the state by submitting a sighting on the museum’s website

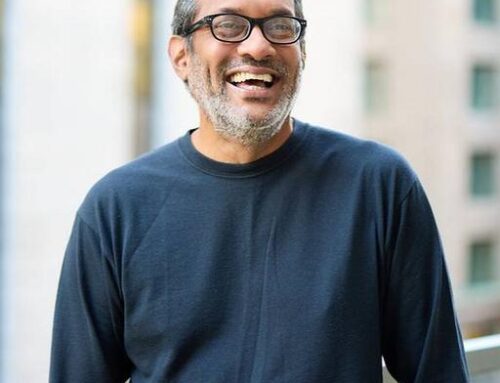

For decades, Susan Campbell has been capturing, banding and releasing hummingbirds, specifically ruby-throated hummingbirds, which are the only hummingbirds that breed in the Eastern U.S.

It’s an effort to learn more about these birds, which she said are not well understood.

The hummingbirds are captured by attracting them with nectar to a cage. The door of the cage closes with a pull rope once they are inside.

Susan Campbell holds a safety pin with bird bands. The bands on the far side of the pin are for songbirds, the bands closer are for hummingbirds. (Spectrum News 1/John Stampf)

“You have to have very specialized training in order to work with the birds. And there are just not that many of us doing this research,” Campbell said.

Her equipment is very precise, which is needed when dealing with these small birds. The bands she places on the leg of the hummingbirds are made of pressed aluminum, measuring 5.6 mm in length, smaller than a songbird’s band

“All bird bands have to have nine characters. We can only fit six characters on a hummingbird band, so we use shorthand by adding the letter prefix,” Campbell said.

Each band is pressed with a number and letter combination to identify the hummingbird when it is captured by researchers. It will stay with the bird the rest of its life.

“We know now from banding that ruby-throated [hummingbirds] can travel as much as two miles in a day, that their home ranges are actually larger than you might think. We also have learned about migration movements, such as the fact that these birds go a different route in the spring than they do in the fall,” Campbell said.

The bands do not hurt the hummingbirds.

Since 1999, the North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences began investigating an increased and unexpected number of hummingbirds in North Carolina during months they would be expected to have migrated to warmer areas.

The goal of the banding project is to document hummingbird weight, body condition, capture date and location and see whether the birds will return to the same location years later, according to the museum’s website.

Banding and tracking the birds is helping researchers discover whether climate change could be affecting migrational habits. It’s still an open question, Campbell said.

“We do know the climate change is affecting the flowers that they visit, especially in the springtime,” Campbell said.

“Those flowers are going to be blooming sooner than they used to be. And some of these flowers, like in the case of the birds coming through the Carolinas, Carolina jessamine is blooming earlier and that is one of their staple food sources as they move north,” she said. “Unless they can keep up with the change in the jessamine blooming, you know they may be out of a food source if things get too far ahead of schedule.”

Susan Campbell puts a band on a hummingbird. (Spectrum News 1/John Stampf)

She said migrating birds are not following food but are traveling a pathway that is genetically laid out for them. Some birds will respond differently and create new paths gradually over time if factors like weather or food supply are affecting their migration, which can then be passed to offspring. Their routes gradually change over time, she said.

Campbell uses her time in the field, like at the Prairie Ridge Ecostation, where she recently banded hummingbirds, to teach others about the importance of banding and what it tells researchers.

“The best part of banding hummingbirds is letting them go,” Campbell said.

She said she has caught the same hummingbird multiple times before and works with researchers across the country to learn more about the beautiful flower-suckers.

Do you want to help track hummingbirds across the state? You can fill out the hummingbird sighting report form on the North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences’ website.

Search

RECENT PRESS RELEASES

Related Post