Environment: Technological revolutions revolutionise society

September 20, 2025

Technological advances spark social revolutions. Deforestation can have a net cooling effect. Warming makes droughts more severe. China leads the energy transition but still a long way from net zero.

Technological revolutions are not just about technology

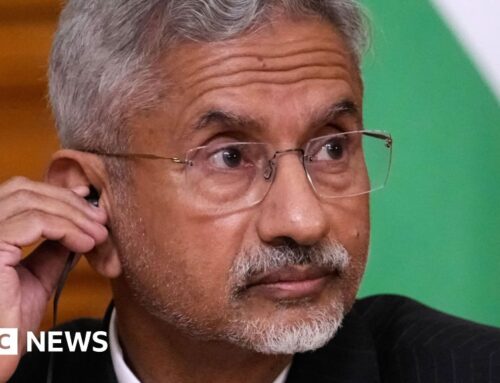

At first sight, the

diagram above looks a neat way of displaying the progression of technologies over the last 250 years. But its underlying logic, developed by the economist

Carlota Perez in 2002, is a bit more sophisticated. Perez suggests each wave (she identified only the first five) represents the appearance of a new techno-economic paradigm that involves not only technical innovation that initiates a revolution in technology, but also revolutions in the economy, finance and society. The resulting new technologies, products and industries displace the previous ones and change people and their skills and the way organisations are run. There is a break with the past, an upheaval of the whole of society, not just smooth, incremental progression.

Regarding the alleged sixth technological revolution, undoubtedly there is a rollout of renewable energy and there are calls for resource efficiency and, despite some efforts to abort these changes, they seem set to continue. Inevitably, these developments are accompanied by some slow changes in wider aspects of global societies. It is not obvious to me, however, that the slowly emerging “green economy” is creating any “revolution” or “paradigm shift” in human behaviour, the economy or society at large. Certainly not a revolution that might produce a rapid, humanity-saving upheaval in power in both senses of the word.

To me, the current evidence indicates any shifts precipitated by the sixth wave of technological progressions will be too slow to avoid the rapidly approaching catastrophes (popularly now termed polycrises) caused by climate change, environmental degradation, widespread inequality, the spread of authoritarianism and the economic crises inevitably and recurrently precipitated by the internal contradictions of capitalism.

It seems much more likely that the ongoing technological developments of the fifth wave — e.g., AI, data centres, e-surveillance, social media, autonomous weapons systems, cryptocurrency — will produce the cataclysmic society-changing revolutions of power, politics, global governance, economics, living conditions, etc. that Perez hypothesises. Unfortunately, these seem more likely to hasten humanity’s demise than prevent it.

“There is no such thing as a win-win revolution” (Ian Angus).

“It isn’t a revolution if the old order remains” (Peter Sainsbury).

More trees are not always good for the climate

A month ago, I described how

forests have been crucial for maintaining a human-friendly temperature around the Earth for the last 12,000 years and how human activities, particularly deforestation, burning fossil fuels and fires, are now turning forests from carbon sinks to carbon sources and increasing global warming. I finished by discussing how global warming is also replacing white, highly-reflective ice sheets and glaciers with darker sea and land which absorb more of the sun’s energy and how this leads to a positive feedback loop, or vicious cycle, and an even greater increase in global warming.

The fraction of sunlight reflected from an area of the Earth’s surface is called the albedo effect and is measured on a scale of 0 (no reflection, all the energy is absorbed) to 1 (all the energy is reflected and none absorbed). To illustrate, ocean has a score of approximately 0.1, forests 0.1-0.2, sand 0.4 and fresh snow 0.8.

Till now, the general assumption has been that clearing an area of forest results in an increase in global warming because there are fewer trees and so less CO2 is absorbed from the air and because much of the felled timber is burnt or left to decay, more CO2 is released into the air.

However, to complicate the deforestation-climate change nexus,

evidence is emerging that the global warming effects of deforestation may have been overestimated by failure to take into account changes to the albedo effect when a forest is cleared. Because tree cover is relatively dark, it absorbs a large amount of the solar energy hitting it (i.e., it has a low albedo score). But when the tree cover is lost, the exposed land, crops or habitation that replace the trees are usually lighter and reflect a much higher proportion of the sun’s energy (i.e., the area has a higher albedo score). This has a cooling influence on the Earth.

The change in the albedo score can markedly influence whether the loss of the trees has a net warming effect (due to the changed CO2 balance) or net cooling effect (due to a higher albedo) on global temperatures. The precise change in albedo depends on

many factors, including the location, type and age of the forest, the particular tree species and even the use made of the felled trees.

Unfortunately, calculations of the effects of the widespread global deforestation that has occurred, on atmospheric CO2 levels and global warming, have seldom taken account of the changed albedo. This has probably led to (sometimes marked) overestimation of the warming effect of forest loss.

The reverse arguments apply to the global cooling effects claimed for stopping deforestation and promoting reforestation and may have led to an overestimation of the benefits of these strategies for the climate.

The point here is not to suggest that we should abandon efforts to stop deforestation or promote tree planting. Rather, it is to stress the importance of rigorous research and monitoring, and accurate estimation of the effects of our strategies on global temperatures, so that we

avoid unexpected outcomes. It is in no-one’s (except the fraudster’s) interests to overestimate the benefits of proposed interventions.

Nor should we ignore the many benefits that trees and forests provide beyond their influence on global warming.

Warming makes droughts more severe

Droughts are common and complex natural hazards that affect the environment, populations and economies. We know that droughts can be caused by both lower rainfall and increased water evaporation from the land (the soil or the vegetation), a process known as Atmospheric Evaporative Demand. We also know that climate change is increasing the AED. However, we know relatively little about drought trends and we have a poor understanding of how AED is affecting the magnitude, frequency, duration or areal extent of droughts.

Examination of

droughts around the world over the last century has provided some clues:

- worldwide, droughts became more severe between 1981 and 2022 – dry regions are getting drier and wet areas are drying;

- over the last 5-10 years, the drying trend has accelerated as a direct result of increasing AED. Globally, AED increased drought severity by 40% in this period but in Australia it was 51% (i.e., the same as low rainfall);

- during 2018-2022, 27% of global land area was affected by drought, 74% greater than during 1981-2017. AED was responsible for 58% of this increase. In Australia, drought-affected areas increased by 119% between these two periods;

- the year 2022 was a record-breaking one for drought with 30% of global land affected. AED was responsible for 42% of 2022’s droughts;

- Australia was the only continent during 1981-2022 where AED was more important than low rainfall as the cause of drought.

In summary, AED is an increasingly important cause of severe droughts. This trend will continue as a warmer world creates more evaporation and, in some regions, reduces rainfall. The implications for extreme weather events, river flows, food production, hydroelectric power generation, local communities, national economies and inter-nation conflict are enormous.

China leads the energy transition but …

China leads the energy transition because of the speed with which it is developing and rolling out renewable energy at home and internationally. Also, because of China’s enormous household and industrial energy consumption, what China does at home has a major influence on global figures.

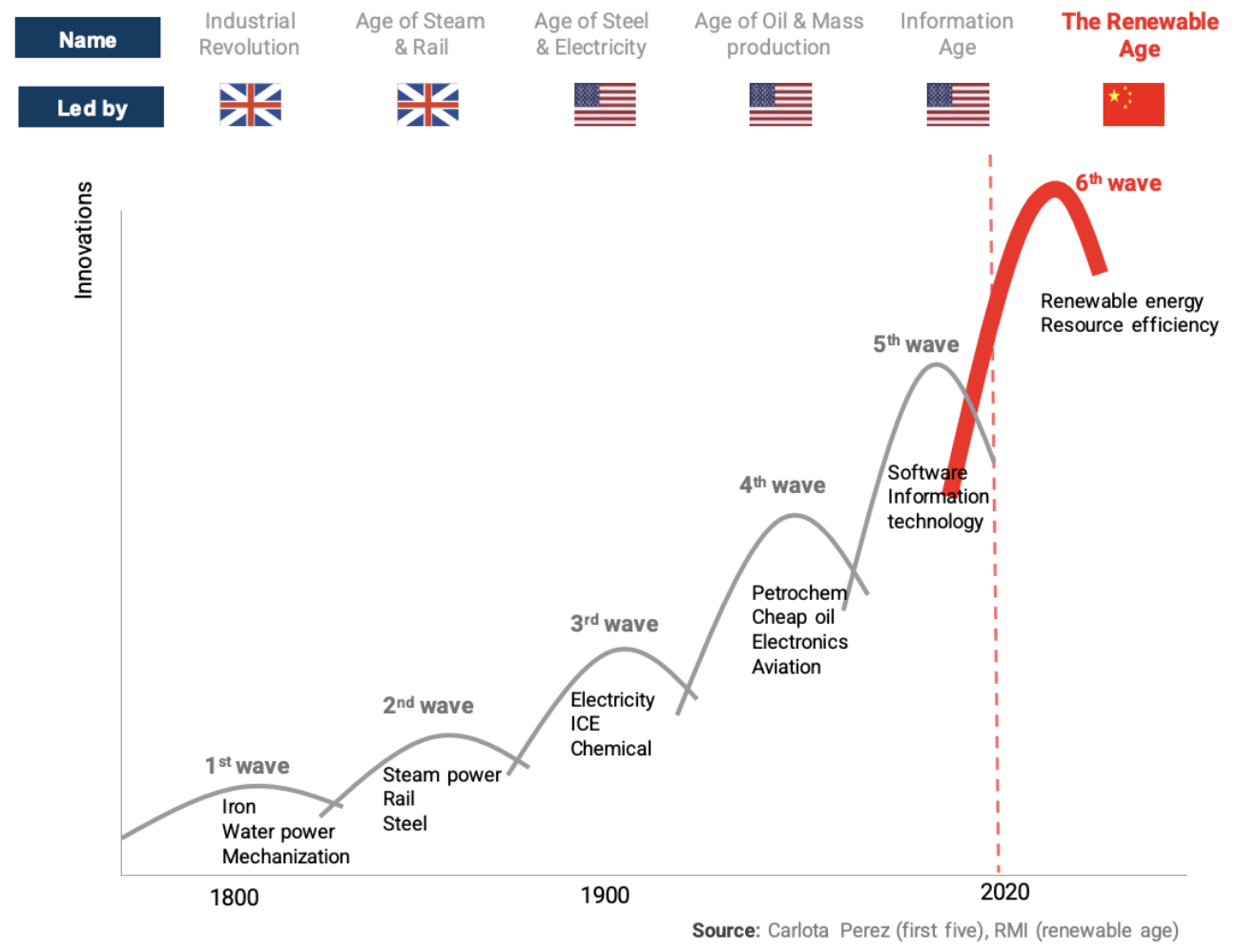

The changes within China are clearly demonstrated in the four figures below. The

top two display:

- on the left, the growth of electricity as a source of energy in China (expressed as final energy consumption) from about 5 EJ in 2000 to 30 EJ in 2023;

- on the right, the growth of wind and solar as sources of electricity generation from about 150 TWh in 2015 to over 2000 TWh in 2025 (with another almost 2000 TWh supplied by bioenergy, nuclear and hydro); and

- in both graphs, the levelling off of fossil fuel use in the last 5-10 years.

The third graph shows that, whereas in the last decade of the 20th century coal supplied 85% of the increasing demand for electricity, by 2024 this had shrunk to 15% and renewables were meeting 80% of the growth.

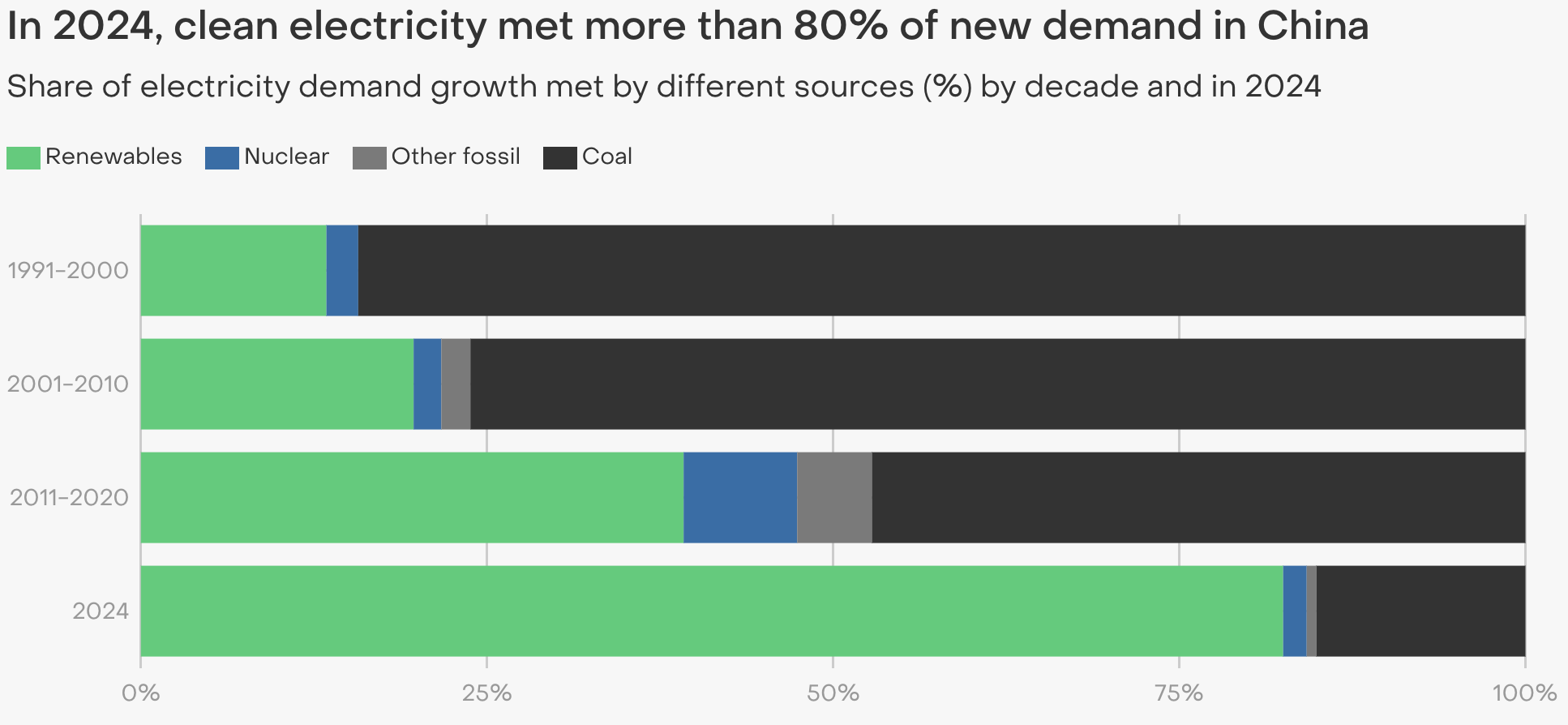

The fourth figure, from Bloomberg Green Daily on 11 September, shows predictions of sales of passenger vehicles in 2025. Annual EV sales in China will exceed the total of all new vehicle sales in the US. In China, EVs are cheaper than conventional combustion vehicles, there is the world’s largest charging network, and the punters have less of an emotional attachment to noise and fumes, although traditionally-powered passenger vehicle sales in China are about 10 million per year.

That’s all excellent news, particularly the speed of China’s transition and that coal may soon not be needed to meet any of China’s still increasing demand for electricity. But there’s another story lurking underneath these figures. Despite the plateaus, in the mid-2020s fossil fuels still supply approximately 55% of China’s energy and three times as much electricity as wind and solar. We will start to get on top of climate change only when fossil fuel use and greenhouse gas emissions plummet.

These figures exemplify the enormous challenges that China still faces to decarbonise its economy and reach net zero or, even better, real zero emissions rather than simply increase its use of renewables. China, the wealthy nation that is most politically determined to make the transition and most progressed in it, still has a long way to go, but the journey for the rest is even longer and more hazardous.

Dam-induced droughts

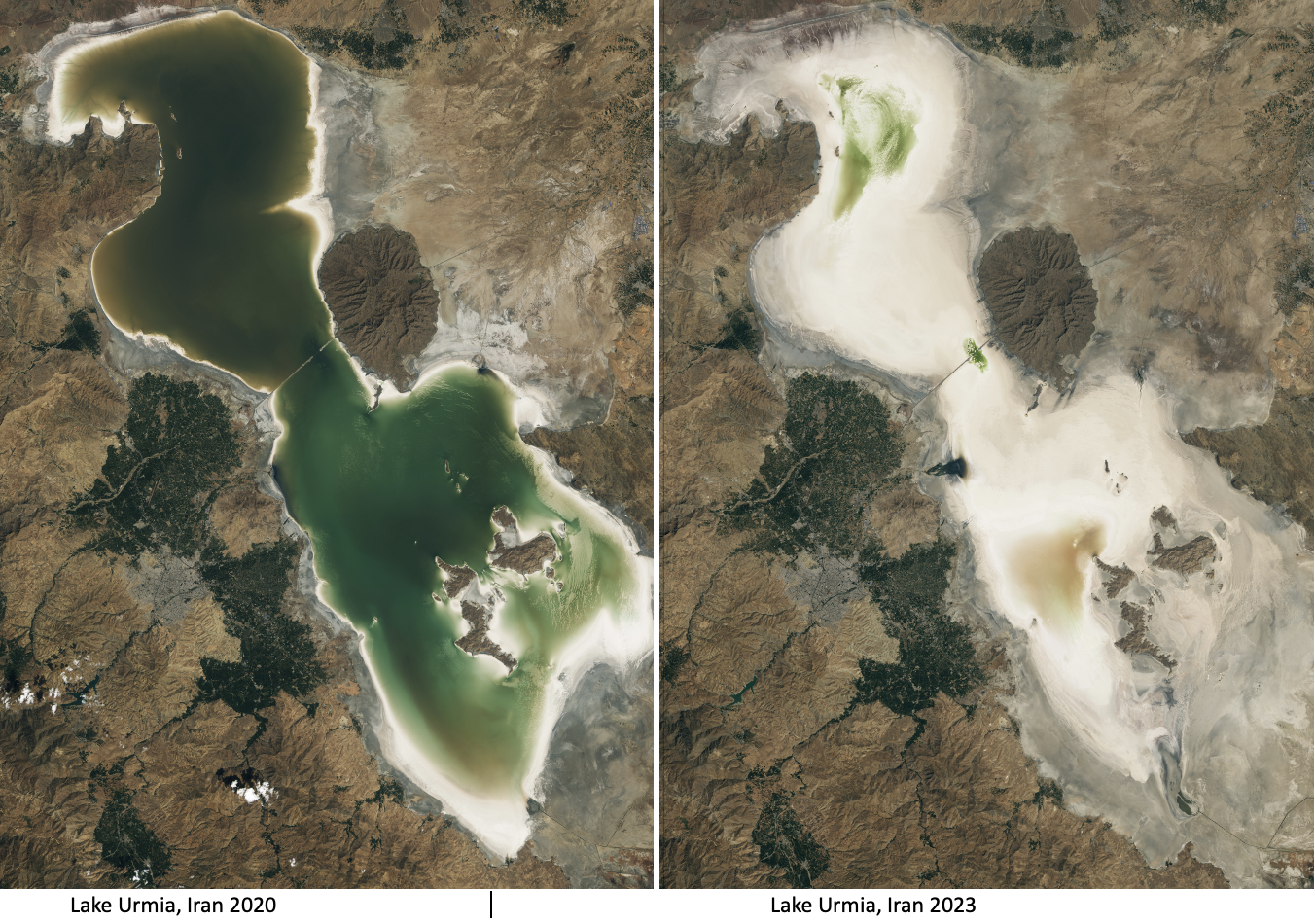

Low rainfall and increased evaporation aren’t the only causes of drought. As farmers and inhabitants of towns in the lower Murray-Darling catchment are well aware, hogging the water upstream can be a major problem. The damage created by

upstream dams (sometimes in another country) is well illustrated by the photographs from Iran and Iraq.

The views expressed in this article may or may not reflect those of Pearls and Irritations.

Search

RECENT PRESS RELEASES

Related Post