Circuit Breaker—Judicial Disconnect on Disarming Cannabis Users | Rockefeller Institute of

September 29, 2025

There is constant tension between the federal and state governments on the issue of marijuana policy. Though 38 states have currently legalized cannabis in some capacity, either for medical or recreational use, cannabis is still a Schedule I drug at the federal level, making it illegal in the eyes of the federal government. This disconnect manifests in numerous ways, including in the gun rights of cannabis users. While the consumption of cannabis may be legal in a person’s individual state, current federal law prohibits a cannabis user from gun ownership. Section 922 (g)(3) of the 1968 Gun Control Act (18 U.S.C. §922 (g)(3)) makes it illegal “for any person who is an unlawful user of or addicted to any controlled substance (as defined in section 102 of the Controlled Substances Act (21 U.S.C. 802))” to possess a firearm. As such, the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms, and Explosives’ standard firearm transaction form (ATF Form 4473), which must be completed when purchasing a firearm from a Federal Firearms License (FFL) gun dealer, requires the applicant to affirm that they are not a cannabis user. In essence, to be law-abiding (federally), a person cannot be both a cannabis consumer and a licensed gun owner; the choice of one means forfeiting the other.

However, as discussed in a previous blog, the Supreme Court’s 2021 ruling in New York State Rifle & Pistol Association, Inc. v. Bruen set a new standard for the constitutionality of gun regulations, diverging from the previous standard of the state’s justification for the regulation needing to outweigh the burden of said regulation. The two-pronged test created in Bruen asked: 1) whether the Second Amendment’s plain text covers the individual’s conduct, and 2) is the regulation consistent with the nation’s historical tradition of firearm regulation.

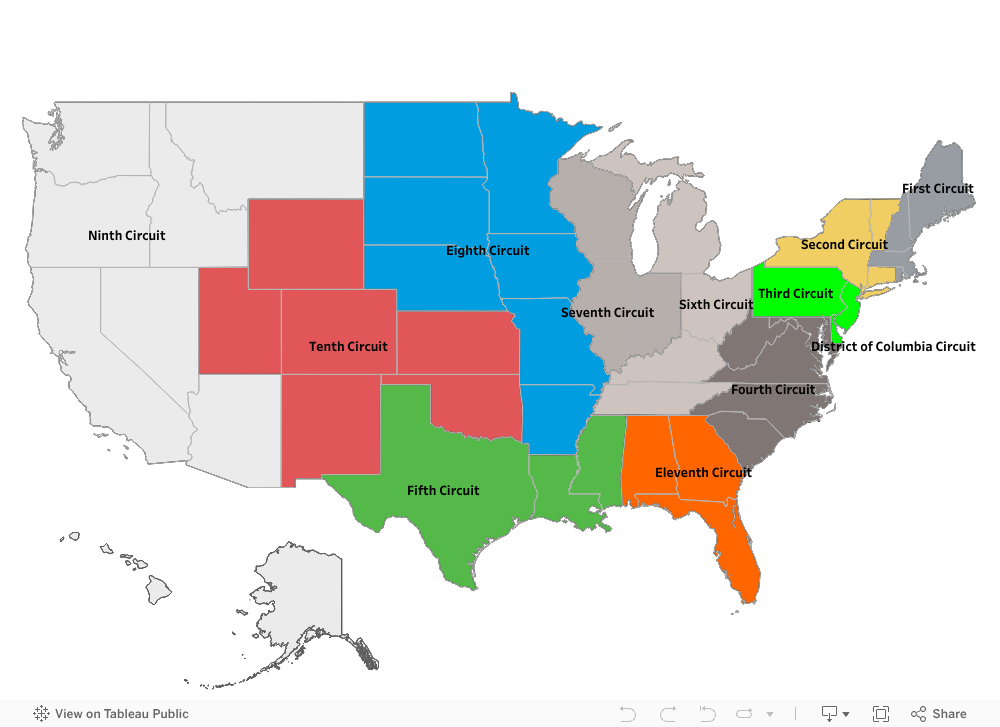

This revised standard has changed the way courts have viewed challenges to the prohibition on cannabis users owning guns in the last few years. Several recent cases have challenged this regulation, questioning whether it can still stand under the revised “history and tradition” standard of Bruen. The result has been that various US Circuit Courts of Appeals have ruled very differently on similar cases, creating a patchwork of judicial precedent where a cannabis user’s ability to own a gun largely depends on where a person resides. While none of these rulings have found 18 U.S.C. §922 (g)(3) unconstitutional, they have differed in the standard that the government must meet to restrict gun ownership.

United States Courts of Appeals

Third Circuit

In United States v. Harris, Harris challenged the prohibition of gun ownership by cannabis users as a violation of his Second Amendment rights, and the case made its way to the Third Circuit Court of Appeals. In their ruling, the Third Circuit conceded that while there is no history of denying cannabis users gun ownership during the founding, Bruen only requires the government to find an analogous restriction, not an identical match. As the court’s opinion stated: “And the analogy turns on similarity in principle, not specific facts: A historical law is a fitting analogue for a modern one if it burdens Second Amendment rights for comparable reasons (the ‘why’) using comparable means (the ‘how’).” The Third Circuit was persuaded that the government’s argument that early American gun restrictions for those who are drunk or mentally ill were close enough “historical cousins” to the modern prohibition on cannabis users to support the current gun owner prohibition in theory. “By taking guns out of the hands of frequent drug users, § 922(g)(3) addresses a problem comparable to the one posed by the dangerously mentally ill and dangerous drunks: a risk of danger to the public due to an altered mental state.”

The Third Circuit did not find that drug users needed to be intoxicated at the time of arrest; their drug use alone could be enough for them to be considered dangerous enough to be disarmed. The court advised that lower court judges should consider the frequency and duration of drug use, the long-term effects of the drug, the drug’s half-life, and the drug’s impact on decision-making and impulse control, among other factors, to decide if the individual in question should be prohibited from gun ownership by the federal government:

Drug users can be disarmed based on the likelihood that they will physically harm others if armed. But here is the distinction: To assess that risk, judges need not wait until a drug user has harmed or threatened another. They may decide whether a drug user ‘would likely pose a physical danger to others if armed’ based on the nature of someone’s drug use and the risk that it will impair his ability to handle guns safely.

In other words, the court was open to some individualized challenges but took a broader view that the potential impairment and danger from drug use was enough to generally restrict the gun rights of cannabis users.

Fifth Circuit

The Fifth Circuit has heard several cases that deal with prohibiting cannabis users from gun ownership—United States v. Daniels and United States v. Connelly (both previously profiled in another blog post), as well as United States v. Hermani. The decisions in these cases collectively set a higher standard for the federal government to be successful in prohibiting gun ownership and present a narrower interpretation of the application of the history and tradition of similar prohibitions. Though the same historical evidence was presented by the federal government as in other cases, the Fifth Circuit was less persuaded by its relevance; the key distinction for the majority of the court was not if the person was a drug user, but if they were intoxicated at the time of the incident that led to their arrest. In Connelly, they said, “Taken together, the statues provide support for banning the carry of firearms while actively intoxicated. Section 922(g)(3) goes much further: it bans all possession, and it does so for an undefined set of ‘user[s],’ even while they are not intoxicated.” The Fifth Circuit requires the federal government to establish impairment through intoxication in order for the prohibition on gun ownership to be upheld. As none of the individuals in any of the Fifth Circuit cases were established to be under the influence, all their convictions were overturned. Currently, the Fifth Circuit standard is the most protective of gun rights for cannabis users.

Eighth Circuit

The Eighth Circuit has shown the most legal evolution in a relatively short amount of time, depending on the type of challenge brought forth. In United States v. Veasley, a facial challenge was brought forth against 18 U.S.C. §922 (g)(3). A facial challenge questions if the law or policy is unconstitutional as written; a successful facial challenge would mean that the law cannot be applied fairly in any circumstance—a higher standard to meet. Given this, the court failed to overturn 18 U.S.C. §922 (g)(3) and affirmed its legality based on the historical precedent. “For our purposes, all we need to know is that at least some drug users and addicts fall within a class of people who historically have had limits placed on their right to bear arms.”

However, subsequent cases such as United States v. Cooper and United States v. Cordova Perez brought forth as-applied challenges to 18 U.S.C. §922 (g)(3), which only challenge the law or policy as applied to the individual in the case. As-applied challenges are limited situations with limited remedy (or recourse)—the court is only addressing the law and its applicability to the individual(s) in the lawsuit—and therefore have a lower threshold to be successful. In Cooper, the court recognized that not all drug users are similar to the mentally ill or dangerous and that if that were the case, the government had not met the burden set in Bruen, and that there may be exceptions to the rule. “These two analogues also frame the relevant questions for resolving Cooper’s as-applied challenge. Did using marijuana make Cooper act like someone who is “both mentally ill and dangerous?” Did he “induce terror,” “pose a credible threat to the physical safety of others” with a firearm? Unless one of the answers is yes—or the government identifies a new analogue we missed — prosecuting him under § 922(g)(3) would be “[in]consistent with this Nation’s historical tradition of firearm regulation.” The case was remanded, or sent back, to the lower court to consider a dismissal.

The Eighth Circuit decided Cordova Perez similarly, relying on the standard which was implemented in Cooper:

But we have already held that without more, neither drug use generally nor marijuana use specifically automatically extinguishes an individual’s Second Amendment right. And the government here did not provide enough evidence to show that marijuana use alone could reasonably be seen to make any user ‘an unacceptable risk of dangerousness’ to others by merely possessing a firearm. Indeed, defining a class of drug users simply by the suggestion that they might sometimes be dangerous, without more, is insufficient for categorical disarmament.

In the Eighth Circuit, under current case law, the government must provide evidence that the individual drug user was a risk of danger because of their drug use or that their drug use made them mentally ill to deny cannabis users their gun rights.

Tenth Circuit

Similar to the cases in the Fifth Circuit, the ruling by the Tenth Circuit in United States v. Harrison also considers intoxication, but doesn’t go as far as the rulings in United States v. Daniels, United States v. Connelly, and United States v. Hermani. The Tenth Circuit found that the government had provided enough historical evidence related to the disarming of intoxicated individuals, but had not provided sufficient evidence to support the restriction of gun rights from those who are not intoxicated at the time of the inciting incident. However, the Tenth Circuit did find historical evidence of the disarmament of individuals who are believed to be a danger in the future, such as Catholics and loyalists. “We thus conclude laws disarming Catholics and loyalists reveal a tradition of disarming those believed to pose a risk of danger, regardless of whether the perceived danger is related to waging war.” The Tenth Circuit found that this had not been adequately considered at the district court level and sent the case back down to allow the government to make the case, and the defendant to rebut, that non-intoxicated marijuana users pose an adequate future risk of danger to be disarmed. “We hold the historical tradition supports a principle that legislatures may disarm those believed to pose a risk of future danger. And we further hold the district court must inquire into the government’s assertion that non-intoxicated marijuana users pose a risk of danger.”

Eleventh Circuit

The Eleventh Circuit case Florida Commissioner of Agriculture v. Attorney General is slightly different than the other cases presented, as it focused only on the denial of gun rights for medical cannabis users, not all cannabis users, and was a challenge to the dismissal of the case by the lower courts. The Eleventh Circuit found that the government’s citation of historical gun regulations regarding felons and dangerous individuals was not comparable to patients who solely participate in a state-approved medical cannabis program. The First Amended Complaint (FAC) submitted in the case makes no reference to the amount or frequency of medical cannabis that the individuals consume, nor does it indicate that cannabis made them impaired or dangerous. Therefore, the Eleventh Circuit found that the government had failed to meet its burden and that the case was remanded to the lower court:

Based on Appellants’ factual allegations, Appellants cannot be considered relevantly similar to either felons or dangerous individuals based solely on their medical marijuana use. Accordingly, the Federal Government has failed, at the motion to dismiss stage, to establish that disarming Appellants is consistent with this Nation’s history and tradition of firearm regulation. Thus, we vacate the district court’s order and remand for further proceedings consistent with this opinion.

Conclusions

The lack of uniformity demonstrated in these cases is an issue for the fairness and consistency of the legal system. When such “circuit splits” arise, the US Supreme Court will often take the case(s) to remedy these inconsistencies and make a single authoritative ruling that is applicable nationwide. The Supreme Court will hold its long conference the week of September 29th, prior to the court’s new term beginning on October 7, 2025. During this time, they will review and decide which cases currently pending before them to hear oral arguments (also known as “granting certiorari”). It is likely, though not guaranteed, that in this year’s long conference that the court may grant certiorari to one or more cannabis gun rights cases to settle this ongoing dispute on the ability of the federal government to restrict the gun rights of cannabis users.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Heather Trela is director of operations and a fellow at the Rockefeller Institute of Government.

Search

RECENT PRESS RELEASES

Related Post