The plastic inside us: how microplastics may be reshaping our bodies and minds

October 12, 2025

Microplastics have been found almost everywhere: in blood, placentas, lungs – even the human brain. One study estimated our cerebral organs alone may contain 5g of the stuff, or roughly a teaspoon. If true, plastic isn’t just wrapped around our food or woven into our clothes: it is lodged deep inside us.

Now, researchers suspect these particles may also be meddling with our gut microbes. When Dr Christian Pacher-Deutsch at the University of Graz in Austria exposed gut bacteria from five healthy volunteers to five common microplastics, the bacterial populations shifted – along with the chemicals they produced. Some of these changes mirrored patterns linked to depression and colorectal cancer.

“While it’s too early to make definitive health claims, the microbiome plays a central role in many aspects of wellbeing, from digestion to mental health,” says Pacher-Deutsch, who presented his work at the recent United European Gastroenterology conference in Berlin. “Reducing microplastic exposure where possible is therefore a wise and important precaution.”

Such discoveries raise unsettling questions: how much plastic do we each carry, does it really matter and can we do anything about it?

Microplastics are shed from packaging, clothes, paints, cosmetics, car tyres and other items. Some are tiny enough to slip through the linings of our lungs and guts into our blood and internal organs – even into our cells. What happens next is still largely unknown.

“Designing a definitive experiment is hard, because we’re constantly being exposed to these particles,” says Dr Jaime Ross, a neuroscientist at the University of Rhode Island in the US. “But we know microplastics are in almost every tissue that has been looked at, and recent studies suggest we’re accumulating far more plastic now than 20 years ago.”

Ross first grew curious about plastics as a teenager, watching her mother’s spaghetti-sauce containers corrode. “Many of us assumed plastic was inert – that it wouldn’t shed or react – but I realised it wasn’t,” she says.

Fast-forward several decades and she began studying what microplastics might be doing to the mammalian brain. Her first study, published in 2023, offered a hint: mice drinking water laced with microplastic particles started behaving differently.

Usually, if you place mice in a brightly lit box, they hug the walls defensively. But those exposed to plastics restlessly ventured into the open – a behaviour more often seen with ageing and neurological disease.

When the mice were dissected, plastic was found in every organ, including the brain, where a key protein linked to brain health, GFAP, was depleted – mirroring a pattern seen in depression and dementia.

Since then, human studies have added to the unease. Microplastics have been detected in the brains of dementia patients, and in arterial plaques from people with heart disease. Those with plastic-laden plaques were almost five times more likely to suffer a stroke, heart attack or die within three years.

Such findings gave me pause. Like Ross, I’d long assumed plastics were harmless, thinking little of chewing ballpoint pen ends, wearing synthetic clothes and reheating leftovers in takeaway containers. So when I heard about a £144 test from Plastictox promising to reveal how many microplastics were circulating in my blood, I pricked my finger and sent off a drop.

Alan Morrison, the chief executive of Arrow Lab Solutions, the US company behind the test, said its goal was to provide people with an estimate of their microplastic exposure, allowing them to make lifestyle changes if they wished. “Sometimes this test is the kick in the butt that they need to get some of this [plastic] stuff out of their house and reduce their exposure,” he says.

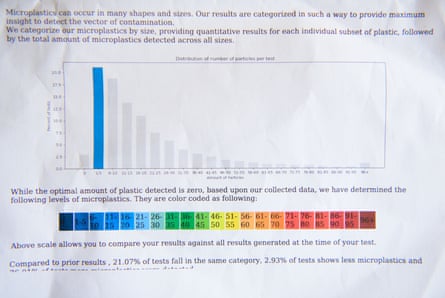

My test detected four microscopic particles – equivalent to about 40 per millilitre of blood. Based on their size, one probably got there through my gut while the other three were likely inhaled, the lab said. Although this places me in the lowest quarter of the 4,000-odd tests it has done so far, “it still represents about 200,000 plastic particles in your bloodstream”, Morrison says. “But considering the average person has over a million, you’re doing comparatively well.”

Yet, as other experts point out, no one really knows what a “safe” level of microplastic looks like. The research field is extremely young and consumer tests are “very premature”, says Prof Stephanie Wright, a microplastics researcher at Imperial College London: “Your test results suggest you’ve got 40 particles per ml of blood – but we don’t know if that’s bad or good, what type of plastic, where they’ve come from, what they’re doing or where they’re going.”

Scientific studies have used a variety of methods, making comparisons between them difficult. Some techniques – including the one used to quantify microplastics in human studies of dementia and heart disease – can suffer from interference from biological tissues. Because of this, their results are far from conclusive and should “be taken with a pinch of salt”, Wright says.

Even if it is possible to accurately quantify the particles in blood or other tissues, it is uncertain whether all microplastics pose the same level of risk.

“Plastics are quite heterogeneous. There are different types, but they also have different shapes, which may influence their harmful effects,” says Dr Vahitha Abdul Salam at Queen Mary University of London. The size of the particles also matters; the smaller they are, the more likely they are to cross biological barriers into organs or cells.

There are further challenges before we know for sure if microplastics are harming us: rodent studies may not translate to humans; because they’re so much smaller, the same-sized plastic particles may be taken up and processed very differently, says Salam.

So where does that leave us? We’re continually exposed to these particles, and “historically, we know that exposure to too many particles is bad”, says Wright, pointing to air pollution as an example. “We just have to understand whether there’s anything about these particles that makes them disproportionately harmful.”

Another pressing question is whether some subjects might be more vulnerable than others. A recent follow-up study by Ross suggested that mice carrying the Alzheimer’s-associated APOE4 gene experienced more severe cognitive decline in response to microplastic exposure than those with less risky genes.

Despite these gaps, many researchers are quietly changing their own habits. “Minimising exposure is probably going to have a benefit overall,” says Wright.

If there’s a silver lining, it’s that although research suggests levels of microplastics in our bodies appear to have sharply risen in recent years, older people don’t seem to contain more than younger ones. “I found that positive, because it tells me we might be able to get them out of our bodies,” says Ross. Identifying ways to expedite this natural process – if it exists – is likely to be a significant research focus in the coming years.

As for me, I can’t unsee those 200,000-odd particles. Whether or not that figure is accurate, it’s hard not to look around my plastic-coated life and wonder how I might start to unwrap it. Reheating leftovers in glass instead of plastic is a good place to start. And I’ll definitely stop chewing ballpoint pens.

How to reduce your exposure

Although it is impossible to avoid microplastics entirely, scientists say there are practical ways to reduce your personal exposure.

Start in the kitchen. “The thing you definitely want to avoid is heat with plastic,” says Ross. “So not cooking your food with plastic utensils, not putting hot beverages or food into plastic.”

Salam says she has stopped microwaving food in plastic containers: “When you expose plastic polymers to heat or direct sunlight, this is what transforms or degrades them into microplastics.”

Ross suggests examining everyday rituals such as making a cup of tea or chopping onions: “Teabags can release a lot of nano and microplastics. Even if the teabag is paper, they can be sealed with a plastic glue, so perhaps try loose-leaf tea. Are you cutting on a plastic board? Because this could also contaminate food.”

Opt for glass or stainless-steel containers, utensils and coffee ware, and use wooden chopping boards instead.

Although tap water contains some microplastics, UK tap water is treated to remove almost all of them and studies suggest that many brands of bottled water contain far more.

Beyond the kitchen, Ross recommends thinking about bedding and personal care products. “Try to have more natural fibres, especially for the things you’re sleeping in – bed sheets, blankets and pillows, because you can inhale nano and microplastics,” she says.

Check the labels on personal care products and cosmetics: although plastic microbeads in, for example, face washes, are now banned, some cosmetics and items such as lotions, lipsticks and eyeshadows may still contain nano or microplastics under names such as polyethylene, polypropylene, polyurethane or acrylates. Also look out for hidden plastics in menstrual products, and opt for those made from 100% cotton or silicone cups.

Airborne plastics are another concern. Although indoor environments generally have higher levels owing to synthetic textiles and furnishings, “tyre-wear from high-traffic environments is another source of microplastics exposure”, says Wright. “In the same way that you’d avoid air pollution by walking down quiet streets, trying not to walk next to traffic and having your windows closed in the car. This should theoretically minimise exposure to microplastics.”

Finally, think about your environmental footprint. Plastics tossed into landfill will slowly degrade, shedding more microplastics. “If you have any plastic items in your house, like plastic containers, repurpose them to store sewing materials and other non-food items,” says Ross. “If you put them in the recycling, they may not get recycled and you’re just adding to the wider problem.”

Search

RECENT PRESS RELEASES

Related Post