Hawaiʻi Balked At Natural Gas. Now, It Could Lower Energy Bills

October 23, 2025

For more than a decade, natural gas was off the table as an energy source for Hawaiʻi, following former Gov. David Ige’s edict that trying to import natural gas would distract the state from its mandated goal of producing 100% of its electricity with renewables by 2045.

Now Gov. Josh Green is bringing natural gas back, a move his team says will lower carbon emissions and electric bills for residents while moving the state toward its renewables goal.

A tentative agreement between Green’s office and Tokyo-based JERA Co. Inc reached last week would bring liquefied natural gas to Hawaiʻi. It would also unlock a $2 billion investment into Hawaiʻi’s energy system — nearly equal to the market value of Hawaiian Electric Co.’s parent company, Hawaiian Electric Industries, which was valued at $2.03 billion as of Wednesday.

It’s the biggest proposed energy deal since NextEra Energy unsuccessfully tried to take over Hawaiian Electric Industries in 2016.

If it goes through, the investment would make JERA a major player in Hawaiʻi, expanding business ties between the islands and Japan, a major tourism market and ancestral home of almost a quarter of Hawaiʻi residents. And it would transform Hawaiʻi’s energy economy.

The proposed deal comes as the Trump administration has expressed hostility to state renewable energy mandates, and renewables in general, while supporting the U.S. liquefied natural gas industry. In June, the U.S. Department of the Interior announced four 20-year agreements under which JERA will purchase up to 5.5 million tons per year of LNG from U.S. suppliers.

The agreements “underscore President Trump’s efforts to unleash American LNG production and the significant role the U.S. LNG industry plays in strengthening the U.S. economy,” the Interior Department said in a news release.

Green traveled to Washington on Wednesday to meet with the U.S. secretaries of energy and the interior, as well as top officials of other agencies, including the military.

“These meetings will support Hawai‘i’s ongoing transition to clean energy,” among other things, the governor’s office said in a news release.

JERA’s six-page, non-binding agreement with Hawaiʻi calls for the company to pay for fuel-flexible infrastructure with the goal of starting with liquefied natural gas — a fossil fuel — and transitioning to renewables such as hydrogen by 2045.

Opening the door to LNG in Hawaiʻi wouldn’t need legislative approval. But anticipated regulatory changes would have to go through the Public Utilities Commission, and projects would be subject to environmental reviews and permitting. HECO would also have to be a major player.

Environmentalists have expressed opposition to the effort. Hawaiʻi Rep. Nicole Lowen, who chairs the House Energy and Environmental Protection Committee, is calling for more details.

The agreement includes nearly two pages of clauses laying out things like challenges Hawaiʻi faces, JERA’s statusas a global energy company positioned to help Hawaiʻi reach its goals and estimated cost savings to residents. Actual terms of the non-binding agreement were limited to three pages, leaving people like Lowen at a loss to comment.

“They have to stop talking in these big generalizations and get real and put something on the table,” she said.

Mark Glick, who heads the Hawaiʻi State Energy Office as the state’s Chief Energy Officer, said a more detailed preliminary analysis is expected by year’s end.

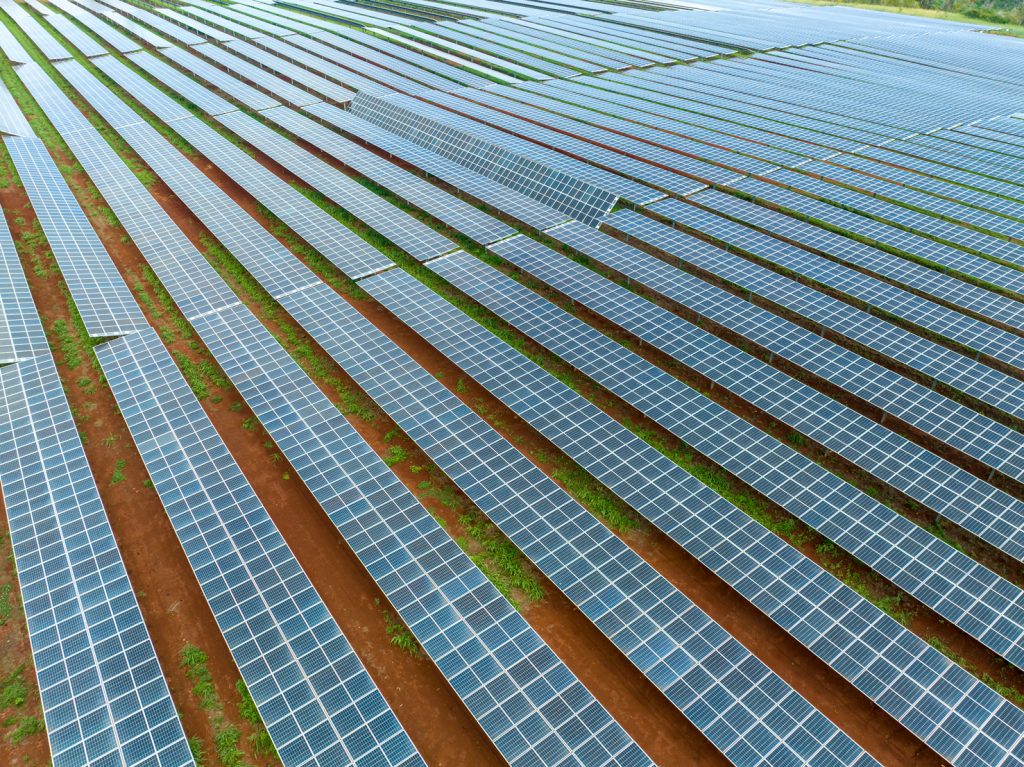

Renewable resources such as large-scale solar and onshore wind farms have emerged as the least expensive ways to produce electricity, and the cost of battery storage systems has also declined in recent years. By law, Hawaiʻi must transition entirely to such renewables by 2045.

In the meantime, the state relies heavily on generators that burn oil, which can be shipped to the state.

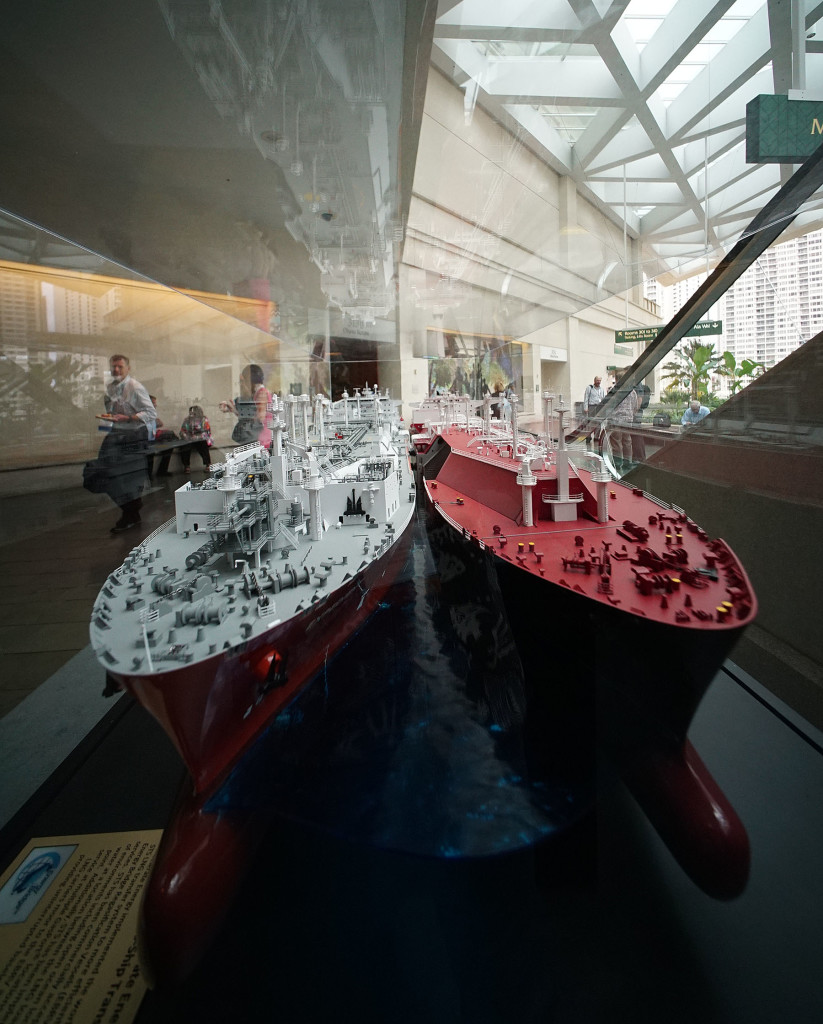

Natural gas is cheaper and burns more cleanly than oil, but can’t be shipped or sent by pipeline to Hawaiʻi. LNG producers super-cool natural gas into a liquid, which can be shipped to users, then turned back into gas at offshore terminals and sent onshore by pipelines.

Former Gov. Neil Abercrombie had been open to using LNG. But former Gov. David Ige took it off the table by flat in 2015, saying it would distract Hawaiʻi from meeting its 2045 renewables mandate.

LNG came onthe table earlier this year, when Green’s State Energy Office issued a study in January highlighting the possibility of using LNG as a transition or bridge fuel. The study identified LNG as a lower-cost, low-emission, short-term alternative to oil, which could be replaced later by hydrogen when such fuel becomes feasible.

The study came out the same month Green issued an executive order supporting renewables.

A few months later, in a speech at the Hawaiʻi Energy Conference in May, Green said LNG had to be part of the mix.

The Green administration had held talks with JERA as early as 2023 when the U.S. Department of Energy had announced plans to create seven regional hydrogen hubs in the U.S., Glick said. The governor had been introduced to the company by Central Pacific Bank Chairman Emeritus Paul Yonamine, a booster of building business ties between Hawaiʻi and Japan who is also a volunteer advisor to Green on Japan affairs.

“Post-Lahaina … we looked at it in a whole different light.”

Hawaiʻi Chief Energy Officer Mark Glick

Hawaiʻi wasn’t the right place for a hydrogen hub, Glick said, but JERA came back over the summer of 2023 to discuss LNG.

“I wasn’t particularly excited at that time,” Glicksaid, but he asked for more information.

JERA came back later that year — about two months after the Maui wildfires, which had dealt a devastating financial blow to HECO and created the specter of massive liability for the company and potential bankruptcy. JERA said it was interested in investing in HECO, helping to help cover potential liability HECO faced as part of an overall LNG plan, Glick said.

While Yonamine had made the introduction to JERA, it was the details of JERA’s plan that interested the energy office, Glick said.

“Post-Lahaina, it became much more serious interest,” Glick said. “And we looked at it in a whole different light.”

The serious interest became an agreement-in-principle with the “Strategic Partnership Agreement,” which Green’s office made public last week.

The agreement anticipates a new procurement process and energy grid modifications aligned for LNG. It also envisions five modernized, fuel-flexible generators being built or updated on Oʻahu. The idea is the generators will be able to use multiple fuels, including LNG and renewables like biodiesel and hydrogen after 2045, Glick said. The cost of at least some of these conversions, Glick said, can be built into existing customer electricity rates.

“LNG is just meant to be a bridge to get us using modernized equipment, not 70-year-old, inefficient power plants,” Glick said.

The agreement proposes that JERA would invest up to $2 billion for LNG infrastructure, including an offshore terminal and pipelines. JERA would benefit by selling natural gas to HECO, Hawaiʻi Gas and shipping companies to power vessels, Yonamine said.

He stressed that there’s no intent for JERA to be Hawaiʻi’s exclusive natural gas supplier.

“The price has to be right,” he said. But Yonamine said that given JERA’s position as a major LNG producer, the company “could provide LNG at the best price for users.”

Using lower-cost fuel will more than offset expenditures on equipment and infrastructure, Glick said.

“The intention is this will create a savings,” he said.

HECO’s spokesperson expressed tempered optimism about the deal, but said any final agreement must align with the utility’s current efforts to modernize its existing grid and encourage big, third-party wind- and solar-farm developers to continue to invest in Hawaiʻi.

“We thought it was a great idea 15 years ago,” said Jim Kelly, HECO’s vice president for government and community relations and corporate communications. “It was our idea to begin with. It’s great that the governor is revisiting this and looking at options.”

Still, Kelly raised numerous questions that the agreement doesn’t answer. The state Public Utilities Commission and HECO already administer a robust procurement regime in which wind, solar and battery storage companies submit proposals to build big projects, from which HECO agrees to buy power under long-term, PUC-approved contracts.

Likewise, HECO is going through the process of creating a new, comprehensive plan to update its grid to handle the new power sources.

It’s unclear, Kelly said, how the JERA agreement would fit into that.

The deal would require a closer look at grid planning to make sure what’s envisioned complements what HECO is already doing, Kelly said. Also requiring a close look is any spending needed to upgrade power generators, which Kelly said is highly regulated.

Glick said the programs proposed under the JERA deal won’t affect current renewables procurement or grid planning.

New procurement regulations mentioned in the agreement, Glick said, are needed to make sure the state can move forward with public-private partnerships in the complex projects the agreement envisions.

Glick commended HECO’s current grid work. But, he said, “What we’ve seen is they’re capital constrained.”

JERA’s capital can change that, he said.

Glick pointed to the state’s mandate to decarbonize its transportation system by 2045, which will massively increase demand for electricity by 2045, when the grid must be powered entirely by renewables.

“Obviously, Hawaiian Electric is looking at that as well,” Glick said. “But, you know, frankly, to ensure that we can grow and have enough generation capacity to be able to handle that, we need to really look at all of the possible opportunities, particularly if there are capital constraints.”

Lowen, the House energy committee chair and a major player concerning Hawaiʻi’s energy policy, said the agreement was too vague to comment on in detail.

“They’re way ahead of themselves,” she said. “First, they need to put a project on the table: What are they proposing and what’s the cost of it?”

Only then would Hawaiʻi utility regulators, as well as the Hawaiʻi Consumer Advocate, which represents rate-payers in matters before the PUC, be able to weigh in. That’s part of the process of approving new projects and regulatory changes, Lowen noted.

“I think we should all have an open mind to consider whatever is being proposed,” Lowen said. “But my suspicion would be that it would be quite expensive, and not necessarily to the benefit of the people of Hawai‘i.”

Environmentalists say they don’t need to know more. They’re adamantly opposed.

Wayne Tanaka, director of the Sierra Club’s Hawaiʻi chapter, pointed to safety concerns, including a 2004 accident at a production facility in Algeria in which 27 people were killed.

He also pointed to operational problems that have shut down offshore regasification facilities for months.

While LNG might burn more cleanly than oil, it is worse, Tanaka said, when factoring in leaks in the production and transportation of the fuel.

In addition, he said, there are questions about costs, which he said could balloon and be passed to consumers. He described the idea of creating a whole new LNG infrastructure as “the Honolulu rail of utilities.”

Finally, Tanaka pointed to the vision of transitioning from LNG to hydrogen in 2045. Current technology simply doesn’t allow it, he said, meaning Hawaiʻi could be stuck with LNG past the 2045 deadline.

“That’s my major concern,” he said. “There’s no end to the bridge.”

Glick said LNG is relatively safe. Terminals are located miles offshore, far from people. And he said natural gas poses a relatively low risk of explosions because it’s lighter than air and dissipates quickly.

Glick acknowledged emissions related to natural gas can make it worse than oil. He acknowledged leaks during natural gas mining and transportation — part of so-called life-cycle emissions — can create greenhouse gas emissions worse than burning oil. But it depends on the locale and regulations in those places, Glick said.

“Some people have sort of cherry-picked instances where it’s definitely worse, and they sort of cite those and say, ‘Well, this is really bad,’” Glick said. “And you know, no one will disagree that it can be really bad.”

But, he said, that’s not always the case. He pointed to British Columbia, Australia and some places in Mexico as examples where environmental protections prevent leakages.

The bottom line, he said, is that using LNG can reduce life-cycle carbon emissions by 50% or more compared with Hawaiʻi’s current practice of burning oil.

“What we’re doing now is extremely bad,” he said. “We’re the most carbon-intensive state in the nation.”

When it comes to hydrogen, Glick said, nobody can predict what the emerging leader in renewable fuels will be in 2045.

Yonamine agreed there are no guarantees. But he said an indication of the fuel’s promise is Japan’s all-out effort to power its economy with hydrogen by 2050.

“The Japanese are banking on this,” said Yonamine, a former president of IBM’s Japan operations. “They’re all in on this.”

Civil Beat’s coverage of climate change and the environment is supported by The Healy Foundation, the Marisla Fund of the Hawai‘i Community Foundation and the Frost Family Foundation.

Search

RECENT PRESS RELEASES

Related Post