Environmental crimes go unpunished. Experts want to equip defenders to fight back

October 30, 2025

(Keystone/AP Photo/Evgeniy Maloletka)

Grave environmental crimes have long gone unpunished. A coalition of experts wants to make sure defenders have the tools to investigate and hold perpetrators to account.

From rivers in Peru poisoned by mining runoff to protected forests in the Democratic Republic of the Congo razed by militias to fund armed efforts, to the toxic legacy of munitions in Ukraine, international crimes often leave behind environmental ruin. Despite their vast ecological and human cost, these offences have long slipped through the cracks of the justice system.

Affected communities are frequently left with little recourse, while NGOs and environmental defenders trying to stop the damage are confronted with a long, winding and technically demanding path to justice. “These crimes are so prevalent around the world, yet there is also a tremendous impunity gap for them,” says Kingsley Abbott, director of the Institute of Commonwealth Studies. “One of the reasons is that those who might be encouraged to investigate them for legal proceedings face so many obstacles.”

The work is painstaking: it demands scientific expertise, legal know-how and the courage to operate in murky, often dangerous terrain.

To close the gap, the UK-based institute, along with a coalition of organisations, including Geneva-based TRIAL International and Justice Rapid Response, launched this summer an initiative to have a group of experts from different fields draft a set of practical guidelines to help investigators navigate those hurdles.

The experts are only just beginning their work after holding a consultation in Geneva last June, and funding is still being worked out, but the organisations hope to launch the final product between 2026 and early 2027.

“We want to empower people who are working on the investigation and prosecution of environmental international crimes with the right tools,” says Abbott.

A legal maze

There is no dedicated convention or framework for prosecuting international environmental crimes. Experts struggle even to define them. Recognising this “historic neglect”, the International Criminal Court (ICC) is currently developing a policy about the environmental component of the gravest crimes, framing them in its latest draft as international crimes – like war crimes, crimes against humanity, torture and enforced disappearances – “committed by means of or that result in environmental damage”.

But precedent is scant. “We do have tools, but we’re not fully using them yet,” says Chiara Gabriele, legal adviser at TRIAL International. These include the Rome Statute establishing the ICC but also national legislation that can be used both for domestic and extraterritorial jurisdiction cases.

One rare success, she says, illustrates the possibilities. In a case led by TRIAL International a few years back, a militia leader who took control of Kahuzi Biega National Park in South Kivu to illegally exploit its timber and gold while terrorising local communities was convicted both for crimes against humanity and for violating DRC’s environmental protection laws.

For victims, recognition of the full scope of the harm is crucial. “For some communities we have worked with, the pollution and destruction of their natural environment also has a cultural, even spiritual, impact,” Gabriele says.

Bridging science and justice

Another hurdle is proving causation. “If you are tortured, it’s more straightforward to prove who the perpetrator is. If a river is polluted and you get cancer and die, it’s more complicated to demonstrate that it happened because of the pollution,” explains Flaviano Bianchini, founder and director of Source International, which is overseeing the scientific section of the guidelines.

Health effects can take years to appear. But science has caught up, and there are increasingly sophisticated methods available. “Today we have technology like isotopic analysis that can trace the lead in your hair, to the sickness, to the exact pollutant, to the place and timeline of exposure,” he says. But these can be costly and require expertise.

Bianchini was recently deployed to Katanga in the DR Congo by Justice Rapid Response to train local NGOs in documenting evidence of pollution from cobalt mining, teaching them how to collect dust and water samples.

Beyond the technical barrier, Bianchini sees an issue of mindset. “You might pay 10,000 euros for a lawyer, but not for the scientist to get the evidence needed by the lawyer,” he points out.

Abbott believes collaboration across disciplines is essential and profoundly lacking at the moment. “Lawyers need to understand the science to be able to present it in a way that’s persuasive and reliable in court, and scientists need to know how the lawyers are thinking and what they need,” he says.

Technical jargon not wanted

Abbott is adamant that the guidelines are meant to be broad and accessible – a loose step-by-step manual. “A lot of these people are non-experts. We want something that’s useful for them so they can gather information in their own countries and regions, because there may not be so-called international experts coming for a while – or ever,” he says. In fact, one of the key asks of those concerned was to “avoid excessive technical jargon and discussions around the legal framing,” says Abbott.

The guidelines will also include tools to assess and handle risks, from how to protect data to how to use international visibility as a deterrent. Environmental and land rights defenders are among the groups who face the highest levels of threats, with at least 142 killed in 2024.

Ecocide and the limits of naming

Discussions for the International Criminal Court (ICC) to recognise a new international crime – ecocide – loom over this work. Proponents argue that it could finally bring large-scale environmental violations before justice. Yet experts remain sceptical. For Bianchini, the debate is largely symbolic. “The laws are already there. Pollution is already a crime. Destruction of the environment and human life are already crimes. If you ask me, it’s a waste of time adding a new name.”

Abbott notes that the guidelines are not intended to resolve any legal debate but rather lay out the existing legal avenues.

One case that may prove existing laws can be leveraged is the destruction of the Kakhovka dam in 2023, causing the Dnipro River to gush out and flood swathes of land across Kherson and Mykolaïv and drain the reservoir needed to cool the Zaporijjia nuclear plant upstream. Bianchini has worked on the case, collecting evidence.

“The Kakrovka Dam was part of the Dnieper River cascade, an industrial heartland stretching back to the Soviet era. Its destruction released decades of accumulated heavy metals. In Zaporizhzhia, the shoreline receded, exposing sand polluted with 70 years of industrial waste. Imagine the hundreds of thousands of people now exposed,” he says.

While Russia and Ukraine have exchanged blame, Ukrainian prosecutors have been working to try it as an international environmental crime and ecocide before its domestic courts. The ICC prosecutor has visited the flooded area, signalling an interest.

Gabriele notes that the Kakhovka dam incident, but also the broader environmental havoc caused by the war in Ukraine, has further pushed the ICC and states to consider the environmental implications of war, which the Rome Statute condemns, though requires a high threshold of scale, damage and intent.

A new green battleground

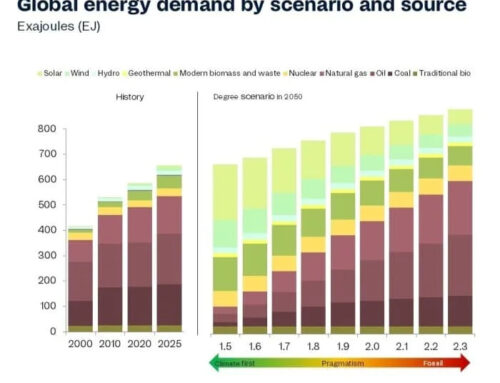

But for the vast majority, international environmental crimes are taking place in inconspicuous contexts, with the rush for critical minerals needed for the green transition as the latest battleground. “We need the energy transition, clearly,” Bianchini says. “But the way we do it now is criminal.”

In Indonesia’s La Bota, nickel waste from coal-powered factories producing 50 per cent of batteries powering Chinese electric cars is poisoning coral reefs. In Peru’s heavily mined Cerro de Pasco, residents face cancer rates four times higher than average. In Congo, air pollution levels due to cobalt vastly exceed limits deemed safe by European authorities.

“It’s even harder because we are challenging the good guys, who paint themselves as the saviours of the environment. But the energy transition as it is now means us with clean cities, and people in places like La Bota, Pasco and Katanga dying so we can have our batteries,” says Bianchini.

The issue may be featured for the first time at this UN climate summit in Belém as developing nations increasingly call for a just transition. While not specifically tailored for climate litigation, Abbott certainly hopes the guidelines can inform those efforts too, as communities seek to hold governments accountable for climate inaction, especially with the International Court of Justice recently ruling that acts such as granting new fossil fuel licenses, providing fossil fuel subsidies or neglecting to regulate emissions could constitute internationally wrongful acts.

“Our desire is that the guidelines will lead to more cases, and hopefully, where appropriate, more convictions for international environmental crimes around the world, whichever the chosen legal framework,” Abbott says. “We’ll then start chipping away at that impunity, creating more opportunities for accountability and even for deterrence.”

Search

RECENT PRESS RELEASES

Related Post