A Closer Look: How Minnesota winters have evolved – and changed – sometimes hurting the ec

December 16, 2025

Minnesota winters. So far so good in the snow and cold department this year, though what transpires over the next few months remains to be seen.

In this month’s A Closer Look, WCCO’s Laura Oakes delves into how our winters have evolved over the past several decades and what that means for our economy, environment, wildlife, and plain old fun in the snow.

From the northern white pines of the moose, to the powdered slopes under the skis of Lindsey Vonn, from rainy days that bring too much, to sweltering heat that cancels fall marathons – it’s not your grandparents’ weather anymore.

“We know the climate has changed.”

Those are the words of Dr. John Abraham who is a professor of engineering and a climate change researcher at the University of St. Thomas.

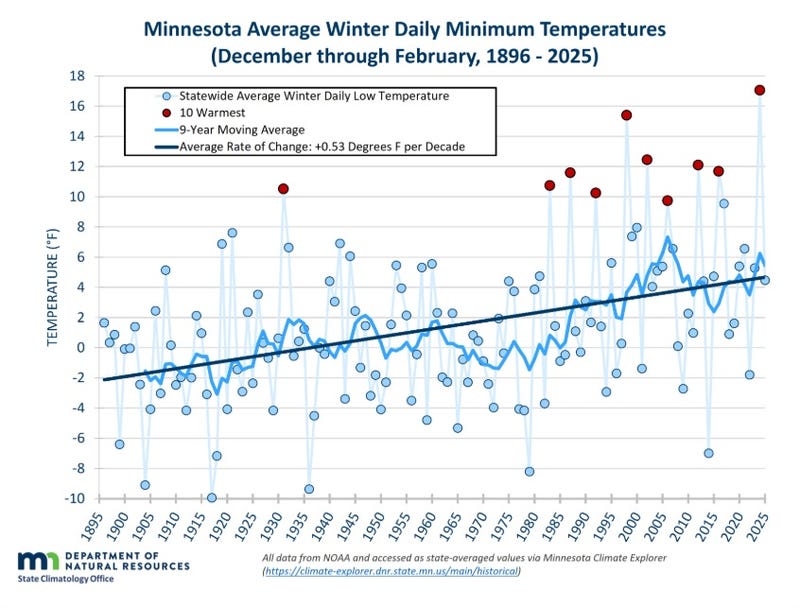

“Winters have warmed much more than summers, and night times have warmed more than daytimes,” says Dr. Abraham. “And so the colder, darker time periods of our day and year have warmed more than when the sun is shining. And there’s a simple reason for that. We have emitted greenhouse gasses into the atmosphere. They trap heat 24 hours a day, every day of the year, and they have a bigger impact when the sun is not shining.”

Less snow. More rain. More extremes.

According to the Minnesota DNR, the state has warmed by 3.0 degrees F between 1895 and 2020, while annual precipitation increased by an average of 3.4 inches. Although Minnesota has gotten warmer and wetter since 1895, the most dramatic changes have come in the past several decades. Compared to 20th century averages, all but two years since 1970 have been warm, wet, or both, and each of the top-10 combined warmest and wettest years on record occurred between 1998 and 2020. Those changes have not slowed in the last five years, and in fact have accelerated.

Abraham says Minnesota had 22 confirmed tornadoes in 2021, and in 2022 the insurance industry lost $2 billion due to extreme weather.

“$2 billion! You can’t run a business losing $2 billion,” says Abraham. “So, you know, people like to complain about insurance companies. Well, this is why. This is why the rates are rising and this is because of increased extreme weather.”

And why does that trickle down to us?

“Weather is driven by two things: heat and moisture,” explains Abraham. “So, when you think about a hot, humid day in the summer, June, July, August, that’s a day that’s got a lot of energy in the atmosphere. And it’s heat and moisture that drives these big storms. So we’re increasing the temperature, which is increasing the heat, but we’re also increasing humidity because as air gets warmer, it can hold more moisture. And a lot of that moisture is coming from the oceans. We’re heating the oceans, which heats the atmosphere, provides humidity to the atmosphere. When you get added heat and moisture, you get bigger, more destructive storms, period. That’s really the connection.”

Photo credit (Getty Images / Tammi Mild)

In Minnesota, where we cherish our nature and our animals so very much, the impact of climate change is real.

“Let’s talk about the moose. So moose populations have been really variable recently, up and down,” Abraham said. “One of the things that has contributed to moose problems is the warm winters have not gotten cold enough to kill ticks. And so the moose in the winter are itchy, and so they scratch themselves on trees to get the ticks off. But that also rubs off their fur and it makes them less able to withstand the cold weather.”

“We’ve had changes to fish populations,” Abraham continues. “We’ve actually had numerous fish die-offs in Minnesota. We’ve had changes to the types of trees and plants that grow in certain regions. If you’re a gardener, you know, you’ve seen the effects of climate change, and this affects everything from home gardening to our logging industry. So, climate change is affecting our economy, both in the State of Minnesota as well as nationally. And it’s also affecting the natural wildlife and natural worlds that we share so much in Minnesota.”

Photo credit (Minnesota Department of Natural Resources)

From the forests to the slopes

258 miles separate the Superior National Forest in northern Minnesota, home to most of the state’s estimated 4,000 remaining moose, from Buck Hill Ski Area in Burnsville, founded in the 1950’s.

It’s still going strong, and still producing Olympic ski racers on almost a yearly basis.

“Maybe where the warmer weather and warmer winters are really playing more of an impact is like, for us as a business, does it rain during Christmas break? You know, do we lose a lot of snow? Do we have to close because of really low temps?” says Nate Birr who is President and Chief Operating Officer of Buck Hill. “Those are the things for us that can throw us off. I think two years ago we had to turn the snow guns back on in February, which is unheard of. And that was because of rain and warm temps and no natural snow.”

Add in the fact that unlike other area ski hills with their own reservoirs, Buck Hill has to pay the City of Burnsville for the 35 to 50 million gallons of water it typically uses in a season to make snow.

How much of a season’s budget goes toward pulling water from the water tower?

“A lot. A lot, yeah. I mean, it’s a big ticket item for us,” says Birr. “And you know, like I said last year, we were able to save 12 million gallons just by getting a cold snap and being able to make more snow, more efficiently with a higher yield. But the reality is, we also have an obligation to our pass holders and to our guests.”

With more of a reliance on manmade snow these days, Birr says they’ve invested in some serious snow gun technology.

“They’re very cool,” he explains. “There’s LED screens on each one of them. We can manage it from up in our shop, when they come on, directionally, which ones, which direction they’re going. They will adjust. They actually have a scale on them, like, what do you want your snow quality to be? Zero being wet, 10 being dry. You can actually say on there, ” make a 7.’ I don’t want it to be too dry or too wet.”

Photo credit (Audacy / Laura Oakes)

Winter in Minnesota is big business

Minnesota’s 18 ski hills are just a slice of the state’s $238 million winter recreation and tourism pie. Other businesses, resorts, outfitters and retail outlets also have had to learn some tough lessons when the weather doesn’t cooperate in a state synonymous with winter–for instance two years ago. Lauren Bennett McGinty is Executive Director of Explore Minnesota in charge of marketing the state to the rest of the country and the world.

“In 2023 to 2024, that was when we really didn’t have anything, there were several counties in the state that declared a drought, there was little to no ice so that people had to cancel plans at festivals and events,” says McGinty. “And so I think what goes through my mind now, specifically after going through that with the community, is how are we preparing for the possibility that maybe we don’t have a lot of snow? Maybe it’s not cold enough for ice, and what does that look like?”

In other words, that means getting creative like in the Explore Minnesota video here.

That Explore Minnesota ad campaign is one of the tools McGinty and her crew use to reach adventurous travelers looking to get in on the “coolcationing” trend by trying a uniquely-Minnesota winter experience.

McGinty says most winters are still conducive to our staples like ice fishing, pond hockey and snowmobiling, but being able to also market and call attention to activities that don’t require snow and ice is crucial.

“So, you can go hiking in snow, but you can also go hiking without snow,” McGinty explains. “You can do fat tire biking without snow. I think more and more people are just trying to find what that balance is. Different destinations that maybe have really cozy resorts and lodges are leaning in to take advantage of the winter no matter what. Come for the cozy and stay for the fireplace and the s’mores and all of that. Even if there’s not snow, it still can be magical.”

Search

RECENT PRESS RELEASES

Related Post