A Groundbreaking Geothermal Heating and Cooling Network Saves This Colorado College Money

February 7, 2026

GRAND JUNCTION, Colo.—The discussions started roughly a decade ago, when an account manager at Xcel Energy, the electricity and gas utility provider, expressed confusion, officials at Colorado Mesa University recalled.

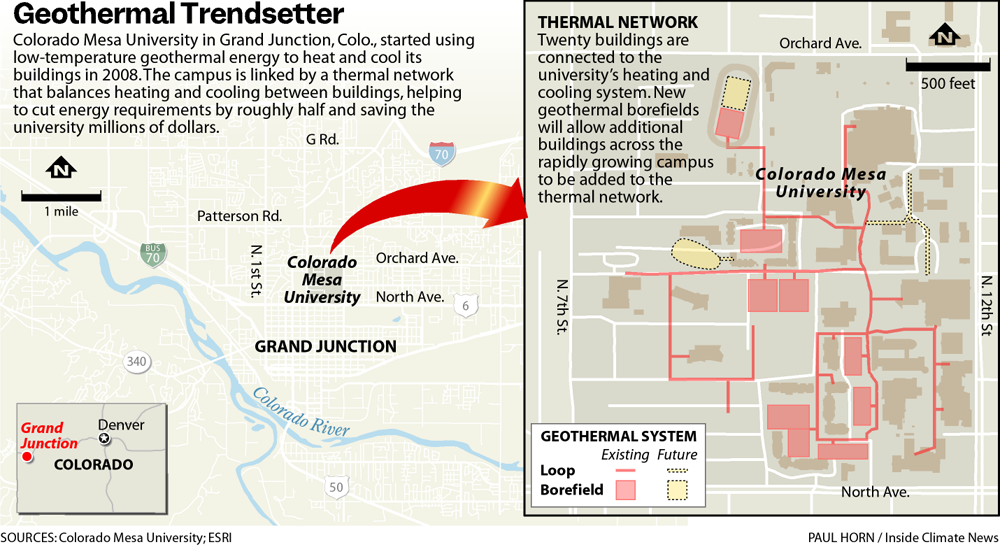

A public school on the state’s remote western slope, Colorado Mesa had recently doubled in size, but its energy usage had hardly budged as it began installing an advanced geothermal heating and cooling system.

Since its geothermal buildout began in 2008, the university has saved more than $15 million in energy costs, money it has passed on to students through lower tuition and more scholarship funding.

Hundreds of boreholes drilled approximately 500 feet beneath athletic fields and parking lots tap low-temperature thermal energy to help heat and cool campus buildings in what is now one of the largest such networks in the nation.

Get Inside Clean Energy

Today’s Climate

Tuesdays

A once-a-week digest of the most pressing climate-related news, written by Kiley Price and released every Tuesday.

Get Today’s Climate

Breaking News

Don’t miss a beat. Get a daily email of our original, groundbreaking stories written by our national network of award-winning reporters.

Get Breaking News

ICN Sunday Morning

Go behind the scenes with executive editor Vernon Loeb and ICN reporters as they discuss one of the week’s top stories.

Get ICN Sunday Morning

Justice & Health

A digest of stories on the inequalities that worsen the impacts of climate change on vulnerable communities.

Get Justice & Health

The system’s high efficiency—later confirmed in an independent analysis by Xcel —means campus buildings require about half as much energy for heating and cooling as similar buildings, allowing the university to expand its campus without a corresponding increase in energy usage.

As the Trump Administration targets renewable energy sources such as wind and solar, developing highly efficient thermal networks like Colorado Mesa’s offers another path for communities to transition away from fossil fuels.

“It’s been the best-kept secret in all of western Colorado for a long time,” Kent Marsh, vice president of capital planning, sustainability and campus operations for Colorado Mesa, said. “We just have never really done a good job of tooting our horn.”

While air temperatures in Grand Junction fluctuate from summer highs in the 90s to winter lows in the 20s, subsurface temperatures here remain approximately 60 degrees year-round. Water circulating through the boreholes is warmed or cooled by the surrounding rock, depending on the season. Ground-source heat pumps in each building provide further heating or cooling as needed.

The university started planning its first geothermal project in 2007. At the time, they sought to provide heating and cooling to just one academic building. Tapping geothermal energy helped Colorado Mesa meet the energy-efficiency requirements to secure state funding.

Cary Smith, the owner of consulting firm Sound Geothermal Corporation and an architect of CMU’s system, realized the university was about to build two additional buildings nearby and suggested they connect all three into a thermal network.

Smith, who worked for decades in the oil and gas industry before turning his attention to geothermal energy, figured the university could save energy costs by connecting the buildings.

The dorm required more heating than cooling, but the academic buildings, where students are crammed into classrooms and lecture halls, required more cooling. To Smith, it was counterproductive to spend energy heating one building while simultaneously spending more to cool the others. If heat could be pulled from the academic buildings and pushed to the dorm, it would reduce the energy needs of all three buildings, Smith said.

Marsh, an engineer by training, and other university leaders were intrigued. Geothermal heating and cooling was relatively new. A thermal network that balanced heating and cooling loads between buildings was largely unheard of, but Smith had recently completed similar projects in Steamboat Springs and Las Vegas.

The administrators at Colorado Mesa, whose mascot is the Maverick, decided to give it a go.

“We had a progressive enough leadership team at the time where we said, ‘you know, we’re not sure 100 percent, but yeah, it sounds like it works, it’s not mad science, let’s do it,’” Marsh said.

The system worked and, as the campus grew, new buildings were added to the network. An 18-inch-diameter water pipe now connects 20 buildings.

On a crisp evening in late October, a men’s rugby team practiced on an athletic field on the CMU campus as the sun set over the Colorado Plateau. The only signs of a vast borefield buried beneath the turf were a few valve plates labeled “Geo” in a nearby parking lot.

A boiler that provides backup heat is rarely used. A bigger challenge is managing excess heat in the summer when thermal energy is drawn from buildings to keep them cool.

Much of this heat is pumped underground and stored for winter use. Additional heat is used to warm the university’s swimming pool, showers and campus irrigation system. These creative uses of waste heat reduce the university’s need for conventional cooling towers that rely on evaporation.

Sound Geothermal estimates that CMU reduced its annual water consumption from the highly constrained Colorado River watershed by 10 million gallons.

Xcel Energy commissioned a report on Colorado Mesa’s geothermal system that confirmed the system’s energy savings.

A “key advantage” of the University’s thermal network is its ability to share heating and cooling loads, the 2023 report concluded. “This load sharing can happen from room to room, floor to floor, and building to building.”

The report measured the system’s “coefficient of performance,” or overall efficiency. A gas boiler, for example, can theoretically have a coefficient of performance as high as one, meaning that for every unit of gas that flows into the boiler, one unit of heat is produced. Air source heat pumps, by comparison, are more efficient. They typically have a higher coefficient of performance, ranging from 2 to 4, because they don’t generate heat; instead, they use fans and compressors to extract heat from outdoor air.

Colorado Mesa’s system, which draws on geothermal energy, stores heat seasonally in underground borefields, and balances heating and cooling loads between buildings, had a much higher coefficient of performance, ranging from 3.6 to 8.9, depending on the time of year.

“That is nothing less than remarkable,” Bryce Carter, the Colorado Energy Office’s geothermal program manager, said. “That performance shows it’s two- or three-times higher efficiency than air source heat pump electrification.”

“When you start projecting that over decades, and these systems are designed to be in the ground 50 or 100 plus years, you’re really talking about substantial savings on energy,” Carter added.

Xcel Energy declined a request to make someone available to discuss the report but said in a written statement that it works closely with the university and commissioned the report to quantify the system’s benefits. Carter, whose office oversees state geothermal energy grants and tax credits, praised Smith’s role in advancing geothermal heating and cooling systems.

“It really has become not just a national but really an international example of the latest generation of the energy network that really shows what’s possible and helps get folks thinking about what might be possible in their own communities,” Carter said.

Smith advised HEET, a Boston nonprofit focused on thermal energy networks, before its work with Eversource Energy to build the first utility-led geothermal heating and cooling system in the nation, which was completed in Framingham, Mass., in 2024.

This story is funded by readers like you.

Our nonprofit newsroom provides award-winning climate coverage free of charge and advertising. We rely on donations from readers like you to keep going. Please donate now to support our work.

There are now more than twenty utility-led thermal energy networks under development or completed nationwide, according to the Building Decarbonization Coalition. Xcel Energy is currently working on three thermal energy network projects, two in Colorado and one in Minnesota, a spokesperson said in a written statement.

The company wants to evaluate the feasibility and cost-effectiveness of thermal networks that align with its 2050 net-zero carbon emissions climate goal, the spokesperson said.

Geothermal heating and cooling tax credits approved under the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 cover 30 percent or more of the total project cost. Unlike its cuts to wind and solar tax credits, the One Big Beautiful Bill Act, passed by Republicans and signed by President Donald Trump in July, largely left geothermal tax credits intact.

The Colorado Mesa and Framingham networks are considered “5th generation” district energy systems that offer the highest energy efficiency among multi-building heating and cooling networks, according to a 2024 study by U.S. Department of Energy researchers published in the journal Energy Conversion and Management: X.

In 2022, Colorado Gov. Jared Polis highlighted Colorado Mesa’s geothermal network as part of The Heat Beneath Our Feet initiative that he led as head of the Western Governors’ Association.

Since then, more than 80 communities in Colorado have expressed interest in developing similar systems and roughly half have begun initial feasibility studies, said Carter, of the state’s Energy Office.

Geothermal heating and cooling is particularly attractive for rural mountain communities where access to natural gas is limited, Carter said. He added, however, that keeping buildings warm in mountain towns, with higher altitudes and more extreme weather, can be difficult.

“Looking at those winter peaks of heating is going to be a big challenge,” Carter said. “How do we make sure that those demands are able to be met?”

While others look to install geothermal heating and cooling, Colorado Mesa continues to expand its network, adding new borefields as additional buildings are brought online.

“It lowers our operating costs,” Marsh said, noting that the system’s higher upfront costs pay for themselves in approximately 6 to 10 years. “It also greatly reduces our carbon footprint. It is just the right thing to do.”

About This Story

Perhaps you noticed: This story, like all the news we publish, is free to read. That’s because Inside Climate News is a 501c3 nonprofit organization. We do not charge a subscription fee, lock our news behind a paywall, or clutter our website with ads. We make our news on climate and the environment freely available to you and anyone who wants it.

That’s not all. We also share our news for free with scores of other media organizations around the country. Many of them can’t afford to do environmental journalism of their own. We’ve built bureaus from coast to coast to report local stories, collaborate with local newsrooms and co-publish articles so that this vital work is shared as widely as possible.

Two of us launched ICN in 2007. Six years later we earned a Pulitzer Prize for National Reporting, and now we run the oldest and largest dedicated climate newsroom in the nation. We tell the story in all its complexity. We hold polluters accountable. We expose environmental injustice. We debunk misinformation. We scrutinize solutions and inspire action.

Donations from readers like you fund every aspect of what we do. If you don’t already, will you support our ongoing work, our reporting on the biggest crisis facing our planet, and help us reach even more readers in more places?

Please take a moment to make a tax-deductible donation. Every one of them makes a difference.

Thank you,

Search

RECENT PRESS RELEASES

Related Post