A stronger, safer, and more prosperous hemisphere: The case for investing in democracy in

December 4, 2025

Bottom lines up front

- Democratic backsliding, transnational organized crime, corruption, and authoritarian influence are driving insecurity, migration, and economic decline across Latin America and the Caribbean.

- Weak rule of law and entrenched kleptocratic networks stifle economic growth and enable criminal organizations.

- The US must shift to a broader investment-driven foreign policy that mobilizes public-private partnerships and supports democratic actors to counter authoritarian regimes and external influence.

This issue brief is the second in the Freedom and Prosperity Center’s “Future of Democracy Assistance” series, which analyzes the many complex challenges to democracy around the world and highlights actionable policies that promote democratic governance.

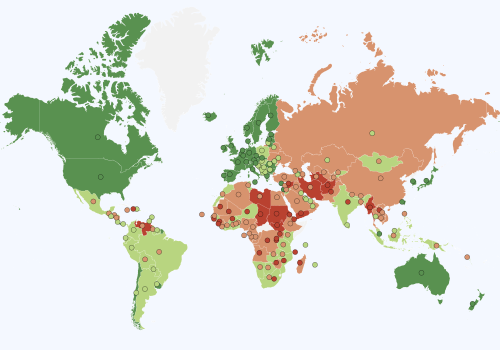

After three decades of democratic and economic progress, Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC) is now losing ground. Between 1995 and 2019, the Atlantic Council’s Freedom and Prosperity Indexes recorded steady gains—a ten-point rise in prosperity and a four-point rise in freedom—that lifted millions out of poverty, deepened the region’s integration into the global economy, and strengthened democratic institutions. Over the past decade, however, this momentum has stalled, and in many countries reversed. Across the region, insecurity has surged, authoritarianism has deepened, and corruption has stifled development, with consequences that reach far beyond its borders.

This reversal is fueling two interconnected crises reshaping the Western Hemisphere: migration and insecurity. Over the past decade, migration—both within the region and toward the United States—has surged. Authoritarian rule in Venezuela, Cuba, and Nicaragua, along with the collapse of Haiti, has driven mass exoduses, while gang violence spurs migration from Central America and hundreds of thousands more have left other countries in search of safety and economic opportunity. Transit states such as Colombia, the Dominican Republic, and Panama face mounting strain on public services, while the United States confronts unprecedented pressure at its southern border.

Regional security is also deteriorating as gangs and transnational criminal networks expand their operations. Mexican cartels dominate the production and trafficking of fentanyl, methamphetamine, cocaine, and other illicit drugs across Latin America and into the United States. The effects of their trade have been devastating, with tens of thousands of overdose deaths annually, particularly in the United States and Canada. Other groups, such as Venezuela’s Tren de Aragua, extend beyond narcotics, driving homicides, corruption, and violent competition over trafficking routes across the region.

Beneath these crises lies a deeper erosion of governance and democracy—one that the United States should support its allies in confronting. Weak rule of law and systemic corruption stifle economic growth and enable criminal networks to thrive. Authoritarian regimes in the region fuel migration, crime, and cross-border instability, while external powers—most notably China—exploit governance gaps through opaque infrastructure projects and debt diplomacy, deepening authoritarian influence. Together, these forces erode state capacity, destabilize the region, and pose a direct challenge to US security and economic prosperity.

Stable, transparent governance in LAC reduces migration pressures, disrupts criminal networks, and creates economic opportunities that benefit both US and Latin American citizens. As the United States reassesses its foreign assistance strategy, democracy assistance can be enacted as a strategic investment to make the hemisphere—including the United States—stronger, safer, and more prosperous. We identify three core issues that pose the greatest challenges but promise the greatest rewards if addressed, and provide recommendations to streamline assistance, expand its scope, and engage business and local actors as funders and partners.

Ultimately, democracy assistance in the region remains one of the most cost-effective investments to advance shared security and prosperity.

LAC is confronting a convergence of three interlinked challenges that erode governance, destabilize societies, and undermine US security and economic interests. Each reinforces the others and fuels the migration and crime that strain the region. The United States should therefore prioritize addressing these challenges through targeted foreign assistance and investment.

Transnational organized crime (TOC) has evolved into one of the most destabilizing forces in LAC. Once localized, criminal groups have grown into sophisticated, multinational networks that traffic drugs, weapons, and people across borders while infiltrating political systems. These networks now operate across nearly every corner of the region, both benefiting from and contributing to weak rule of law and institutional resilience.

Gangs and TOC actors are among the main drivers of insecurity in the region. Although the region comprises less than 10 percent of the world’s population, it accounts for roughly one-third of global homicides. Central America maintains high levels of insecurity, while countries such as Mexico, Ecuador, Colombia, and Peru have experienced sharp increases in violent crime as cartels and gangs battle for control of trafficking routes, urban neighborhoods, and illicit economies. The costs are profound: Latin American Public Opinion Project data show that intentions to emigrate are significantly higher among individuals exposed to crime, while nearly one-third of private sector firms in Latin America cite crime as a major obstacle to doing business, with direct losses averaging 7 percent of sales. Insecurity is not only displacing communities but also undermining prosperity and eroding trust in governments.

The drug trade remains one of the most profitable and damaging arms of TOC. Mexican cartels—particularly the Sinaloa Cartel and Jalisco New Generation Cartel—are the hemisphere’s principal suppliers of fentanyl, methamphetamine, cocaine, and heroin. Their operations extend beyond Mexico and the United States, reaching deep into Colombia, Ecuador, Central America, and increasingly Canada. In 2024, US Customs and Border Protection seized over 27,000 pounds of fentanyl at the southern border—up from 14,700 pounds in 2022. The human toll is staggering: Fentanyl overdoses now kill more than seventy thousand people annually in the United States.

TOC represents not only a law enforcement problem but also a profound institutional and governance challenge. These groups thrive in contexts marked by weak institutions, porous borders, and entrenched impunity. Venezuela’s institutional collapse, for example, directly enabled the rapid growth of the Tren de Aragua gang from one prison to over ten countries. Once established, criminal networks act as corrosive forces—penetrating police forces, judicial systems, militaries, local governments, and even segments of the private sector. Their influence extends into the electoral arena as well: In Mexico’s recent elections, criminal actors not only financed campaigns for local candidates but also threatened and assassinated others, further distorting political competition and undermining democratic accountability. Left unchecked, TOC erodes public trust, distorts markets, and makes effective governance nearly impossible, fueling a self-reinforcing cycle of violence, displacement, and state fragility.

The once relatively stable country of Ecuador has become a battleground among Mexican drug trafficking organizations (DTOs) in recent years, with authorities estimating that 70 percent of the world’s cocaine passes through its ports. As Ecuador has emerged as a vital transit country, Mexican DTOs have partnered with local crime syndicates to deepen their control in the country, buying the influence of politicians, judges, and security officials. The main actors vying for control of drug shipment routes include the Sinaloa Cartel, its rival the Jalisco New Generation Cartel, and their affiliated local crime syndicates. These structures tax and protect cocaine flows moving from border regions toward export terminals, targeting trucking firms, port and warehouse staff, and local authorities.

Ecuador’s security crisis, however, is not simply a matter of state versus gangs, but of deep institutional infiltration. The landmark Metástasis investigation (2023-25) exposed how judges, prosecutors, police officers, politicians, a former head of the prison authority, and other high-ranking officials systematically protected or advanced the interests of organized crime for years. In exchange for cash, gold, luxury cars, and other benefits, officials allegedly released gang leaders, altered prison conditions, and sabotaged investigations.

Despite these challenges, Ecuador’s government—reelected in 2025 with a mandate to confront organized crime—has pledged to continue the fight. Yet its experience highlights a critical lesson: Defeating gangs and cartels cannot be achieved solely through crackdowns or arrests; it also requires rebuilding institutions.

In many countries, governments have proven unable or unwilling to meaningfully confront TOC. Others have stepped up efforts to target these groups through mano dura policies or intensified security operations that, while capable of disrupting trafficking routes, cannot by themselves dismantle transnational criminal networks. Addressing the governance gaps that allow these organizations to thrive is therefore crucial. In this context, US leadership remains essential. Given the cross-border nature of these networks, lasting, viable solutions demand a coordinated regional response. By leveraging its diplomatic influence, security partnerships, military capabilities, and development tools—including technical assistance, institutional support, and investment incentives—the United States can help foster cross-border cooperation, strengthen judicial and prosecutorial capacity, and reinforce institutions to shield them from criminal infiltration. Paired with diplomatic and intelligence support, democracy assistance can play a critical role in disrupting organized crime, safeguarding US security interests, and creating the conditions for more prosperous and resilient communities across the hemisphere.

Declining rule of law has become an increasingly urgent concern in LAC, as regional indicators have steadily worsened in recent years and several countries have registered some of the steepest declines worldwide. This deterioration both enables transnational organized crime and authoritarianism and imposes enormous costs on national economies. Research by the Atlantic Council’s Freedom and Prosperity Center shows that the rule of law is the single most influential factor for long-term economic growth and societal well-being. Liberalizing markets is not enough: Legal clarity, judicial independence, and accountability are the foundations of effective governance and thriving economies. This is particularly relevant in Latin America, where corruption remains the region’s Achilles’ heel—undermining public spending, fueling fiscal deficits, and weakening financial oversight. Across the region, higher corruption levels are consistently associated with lower gross domestic product per capita and reduced foreign direct investment, costing countries and investors billions in lost growth and opportunity

A particularly distorting force in the region’s economy is the prevalence of kleptocratic networks. These are not isolated acts of graft, but coordinated, systematic efforts to capture state resources and extract rents for political and economic gain. Such networks often comprise coalitions of corrupt political elites, complicit business actors, and criminal organizations. They co-opt the judiciary and prosecutors, while silencing investigations and oversight bodies. Their actions stifle competition, discourage entrepreneurship, and produce unfair monopolies that sideline foreign investors, while draining public coffers of resources needed for development.

The scale of these operations can be staggering. In Venezuela, over the past two decades, ruling party figures and business allies have been suspected of siphoning off as much as $30 billion in public funds through transnational schemes involving front companies, illicit contracts, and offshore accounts. This systemic kleptocracy has not only enriched elites but also accelerated Venezuela’s economic collapse, fueling one of the worst migration crises in the region, including to the United States. In Peru, the Club de la Construcción scandal revealed how an informal cartel of major construction companies colluded to divide up public works contracts in exchange for bribes to officials in the Ministry of Transport and Communications. The scheme operated for more than a decade, was worth billions in inflated contracts, and sidelined honest competitors while draining infrastructure budgets.

The Dominican Republic illustrates how strengthening the rule of law can improve governance and unlock economic opportunity. Since President Luis Abinader took office in 2020, the government has carried out anti-corruption reforms. The administration appointed an independent attorney general and empowered the public ministry to investigate and prosecute high-level corruption cases. The government has also advanced transparency and digitalization reforms to make interactions with public agencies—especially in procurement—more open, efficient, and resistant to abuse. In addition, the country has aligned with key recommendations from the Financial Action Task Force, including by passing a revamped Anti-money Laundering and Illicit Finance Law, which has constrained kleptocratic networks and organized crime.

These measures have begun to restore trust in public institutions. Procurement processes are now more transparent and competitive––with twenty thousand new suppliers registered—while new safeguards better protect against corruption. Since 2020, the Dominican Republic’s score on Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index has improved by eight points. Investor confidence has followed: Foreign direct investment reached record highs in 2024, while trade with the United States expanded sharply. US goods exports to the Dominican Republic grew to $13 billion that year, producing a $5.5 billion trade surplus for the United States.

Some of the region’s largest corruption scandals have been uncovered by investigative journalists and independent prosecutors. Yet in many cases, impunity prevails, and little progress is made toward prevention or sustained accountability. Strong judicial institutions, effective anti-corruption reforms, and governance are essential for stability and growth. Predictable, rules-based environments make countries far better partners for both domestic and US businesses—creating jobs, expanding markets, and strengthening local economies. Such efforts can also reduce migration pressures, as corruption has been shown to drive both legal and irregular migration. As with TOC, for the United States, supporting rule-of-law reforms is therefore a strategic investment in building a more prosperous, democratic, and secure hemisphere.

LAC is home to several resilient democracies that remain close US allies and important trading partners. Yet the region also contains some of the world’s most entrenched dictatorships—Cuba, Venezuela, and Nicaragua—which pose direct threats to stability. Between these extremes lie eight nations that Freedom House classifies as “partly free,” many of which experienced additional democratic declines in 2025. Countering democratic backsliding and protecting the global order is not a values-based mission; it is essential to safeguarding US security, economic interests, and the long-term prosperity of the Western Hemisphere.

The region’s authoritarian regimes illustrate the stakes. Economic collapse and repression have forced 7.7 million Venezuelans, 500,000 Cubans, and tens of thousands of Nicaraguans to flee over the past decade. These governments also generate acute security risks. Nicaragua has positioned itself as a conduit for extra-regional migration, inviting travelers from Africa, Asia, and the Caribbean to enter visa free and transit toward the US border. The Daniel Ortega regime has further been linked to targeted harassment and even assassinations of dissidents abroad, including the 2025 killing in Costa Rica of Roberto Samcam Ruiz, a retired Army major and government critic.

Similarly, the consolidation of Venezuela’s dictatorship has transformed the country into a hub for criminal organizations, including Colombian paramilitary groups and Tren de Aragua. The Nicolás Maduro regime has hosted the Wagner Group while continuing to rely on Russian military advisors, Iranian oil technicians, and Chinese surveillance systems to tighten internal control and repress dissent. Members of the regime have been linked to drug trafficking––most notably through the illicit military network Cartel de los Soles––and, in late 2024, Maduro threatened to invade neighboring Guyana.

At the same time, external authoritarian powers—especially China—are expanding their footprints, particularly in “partly free” states where institutional checks are weak. China exploits governance gaps through surveillance technology, opaque infrastructure deals, and strategic investments in critical sectors—often at the expense of US influence and market access. Over the past decade, China invested $73 billion in Latin America’s raw materials sector, including refineries and processing plants for coal, lithium, copper, natural gas, oil, and uranium. In Peru, Chinese firms paid $3 billion to acquire two major electricity suppliers, giving them what experts describe as near-monopoly control over the country’s power distribution and edging out competitors. Beijing also provides critical technology to regional authoritarian governments and at-risk democracies. In Bolivia, the government deployed Huawei’s “Safe Cities” surveillance systems, raising concerns about mass data collection, particularly during elections.

Under President Rafael Correa, Ecuador—alongside Bolivia’s Evo Morales and Venezuela’s Hugo Chávez—pursued closer ties with foreign authoritarian powers, betting heavily on Chinese financing and infrastructure. A centerpiece of this strategy was the $2.7 billion Coca Codo Sinclair hydroelectric project, awarded under opaque terms to Chinese firms, primarily Sinohydro, as part of an $11 billion package of oil-backed loans and infrastructure deals.

The project soon became a symbol of the risks of such arrangements. The dam has been plagued by structural flaws, including more than seventeen thousand cracks, severe environmental damage, and corruption allegations implicating senior officials. State agencies attempted to downplay or conceal the problems, but by 2024 the facility had ceased functioning altogether. Experts estimated that repairing the damage could cost tens of millions of dollars, erasing much of the project’s intended economic benefit. Beyond its technical failures, Coca Codo Sinclair left Ecuador financially vulnerable. In 2022, the government was forced into arbitration and subsequently renegotiated more than $4 billion in debt with Beijing, further compromising its fiscal position and weakening investor confidence. The episode illustrates how opaque partnerships with authoritarian powers can undermine democratic accountability and damage economic stability.

These developments underscore the importance of countering authoritarianism in LAC as both a security and economic priority for the United States and the region. Betting on democratic renewal in Cuba, Nicaragua, and Venezuela is critical to restoring stability in the hemisphere. At the same time, it is equally important to strengthen “at-risk” democracies to prevent further backsliding. Targeted investments in political party development, anti-corruption reforms, and transparency measures can bolster resilience in these states and reduce the appeal of authoritarian alternatives. Pushing back against China’s growing economic and geopolitical influence in the hemisphere is also essential. By leveraging diplomatic and trade tools, the United States can position itself as a credible alternative to China—particularly by mobilizing investment, fostering public-private partnerships, and advancing governance reforms that strengthen transparency and accountability. Doing so is vital for freedom and security in the region and creates opportunities for business and investment.

Insecurity, weak rule of law, and authoritarianism represent growing threats to freedom and prosperity in the Western Hemisphere. As outlined above, TOC, entrenched corruption, and authoritarian regimes impose heavy economic costs on LAC and undermine democratic governance. At the same time, these forces drive mass migration, placing immense strain on transit and destination countries. Tackling these challenges is a strategic win-win: It can enhance US security and economic interests while advancing stability and prosperity in the region.

As the United States reassesses its foreign policy and democracy assistance strategy in LAC, it should make use of its full range of diplomatic, security, trade, and investment mechanisms—including targeted democracy assistance—to address these challenges.

The proposed shift toward an investment- and trade-driven foreign policy can go hand-in-hand with democracy assistance and reform. The United States can mobilize financial and diplomatic tools to expand investment as an alternative to Chinese influence, while incentivizing governance, transparency, and accountability reforms that strengthen the region’s resilience against the challenges outlined above.

- Leverage the US International Development Finance Corporation (DFC) to provide an alternative to Chinese financing and invest in projects that strengthen democratic resilience through economic modernization, digitalization, and high-quality infrastructure—particularly in areas vulnerable to authoritarian influence. As Congress prepares to revisit the DFC’s authorizing legislation, it should ensure the agency has long-term funding to deploy its range of tools—including debt financing, equity investments, and political risk insurance—across the region.

- Work with Congress to pass the Americas Act to establish regional trade, investment, and people-to-people partnerships with like-minded nations, fostering long-term private sector development. Use this framework to advance transparency and institutional autonomy reforms—particularly through the proposed Americas Institute for Digital Governance and Transnational Criminal Investigative Units—to ensure partner countries strengthen anti-corruption prevention, detection, and prosecution.

- Use regional forums—such as the Summit of the Americas—to advocate for governance, security, transparency, and accountability reforms to strengthen the resilience of democratic allies and counter authoritarian regimes. The United States should link political reform benchmarks to investment incentives, offering “carrots” for change through regional development commitments.

A safer and more democratic Western Hemisphere directly benefits economic development and business. The United States should position its domestic and the Latin American private sectors as active partners in strengthening democratic resilience, not just as passive beneficiaries of stability.

- Revive and operationalize America Creceto incentivize and promote reform-linked investments, infrastructure projects, and job creation across the region to counter Chinese influence and advance US interests while bolstering political will through the DFC. Participation should be tied to clear benchmarks on transparency, labor rights, and legal predictability.

- Forge public-private partnerships that co-finance civic education, anti-corruption initiatives, and local development projects, particularly in high-risk areas vulnerable to TOC recruitment and migration.

- Mobilize Latin America’s business elites—among the greatest beneficiaries of economic and democratic collaboration with the United States—to push for and co-fund democracy and governance programs in their home countries. Leading companies, philanthropic foundations, and chambers of commerce should be engaged as active partners in advancing reforms.

- Strengthen and engage with regional initiatives like the Alliance for Development in Democracy—championed by Costa Rica, Panama, the Dominican Republic, and Ecuador—that integrate the private sector into democratic reform and good governance agendas.

While the State Department plays a central role in US democracy assistance, the scale and interconnected nature of the region’s challenges—spanning security, rule of law, and authoritarian influence—demand a coordinated, whole-of-government approach.

- Leverage the Pentagon’s Defense Institution Building program to strengthen law enforcement reform, bolster rule-of-law resilience, and build institutional capacity to counter transnational crime and human trafficking.

- Provide technical assistance and legal expertise through the Department of Justice, Drug Enforcement Administration, and Bureau of International Narcotics and Law Enforcement Affairs to help countries develop national frameworks that protect transparency, law enforcement, and sovereignty in investment decisions.

- Double down on rule-of-law reforms and projects, particularly those targeting organized crime and corruption. Support vetted law enforcement units, independent anti-corruption actors, and judicial reform initiatives through US, private sector, and multilateral funding channels, including the Organization of American States, the Inter-American Development Bank, and the Open Government Partnership.

- Protect the key pillars of democratic institutions from co-optation by TOC, kleptocratic, or authoritarian actors. This must include courts, election management bodies, political parties, and critical government agencies such as those overseeing infrastructure, development, procurement, and public prosecution. Emphasis should be placed on institutional independence, combating and preventing corruption, and ensuring sustainable financing to strengthen resilience.

- Apply targeted sanctions, Global Magnitsky measures, and trade conditionality to dismantle kleptocratic networks, prosecute corrupt actors, and reward credible reformers.

- Advocate for and support the implementation of global security and anti-corruption standards—including recommendations from the Financial Action Task Force and its LAC branch, GAFILAT (Grupo de Acción Financiera de Latinoamérica), on money laundering, organized crime, and illicit finance—to disrupt TOC and kleptocratic funding networks while fostering safer and more competitive business environments.

Regional local actors—both within and outside of government—are often the most credible and resilient defenders of democratic governance. The United States should deepen its engagement with these networks while identifying and empowering new partners.

- Partner with trusted community institutions—including religious organizations, civic leaders, businesses, and grassroots groups—on programs that prevent gang recruitment, reduce crime, and promote integrity in high-risk areas.

- Strengthen governance mechanisms to build sustainable local capacity to counter corruption and transnational organized crime.

- Expand the partner ecosystem to include diaspora networks and local community groups, leveraging their resources, expertise, and transnational connections to reinforce democratic resilience.

Bipartisan US support for organized opposition in Cuba, Nicaragua, and Venezuela has been a cornerstone of regional democracy policy and should be sustained and expanded. At the same time, Washington should back democratic movements and reformers across the hemisphere where authoritarian influence is taking hold.

- Sustain support for dissidents and democratic movements in Cuba, Nicaragua, and Venezuela to prepare the ground for eventual political transitions.

- Invest in independent media.

- Support the next generation of democratic leaders through fellowships, trainings, and political party development, prioritizing authoritarian and high-risk states.

- Collaborate with electoral commissions, legislatures, and political parties with an emphasis on internal democracy, campaign transparency, and long-term institutionalization.

- Assist governments in auditing and renegotiating opaque infrastructure or digital agreements—particularly those with authoritarian powers—that undermine sovereignty, transparency, and public accountability.

The recommendations offered here provide a roadmap to confront the region’s most pressing security and prosperity threats by pairing diplomacy, trade, and investment tools with targeted democracy support. By leveraging the United States’ entrepreneurial capacity and its ability to mobilize multinational and public-private partnerships, reforms can be made more attractive, sustainable, and impactful. This is not charity—it is a strategic investment that advances both US and LAC interests.

At relatively low cost, democracy assistance strengthens governance and open markets in ways that directly serve US security and economic priorities. It helps dismantle transnational criminal organizations, kleptocratic networks, and corruption, while countering the growing influence of authoritarian regimes inside and outside the region. These efforts reduce the flow of illicit drugs and irregular migration, create more reliable markets for businesses, and build stronger partnerships with governments that share democratic values. The outcome is clear: a stronger, safer, and more prosperous hemisphere.

about the authors

Antonio Garrastazu serves as the senior director for Latin America and the Caribbean at the International Republican Institute (IRI). Prior to this role, he led IRI’s Center for Global Impact and from 2011 to 2018 was resident country director for Central America, Haiti, and Mexico. Garrastazu has worked in academe, the private sector, and government, serving in the Florida Office of Tourism, Trade and Economic Development under Governor Jeb Bush. He holds a bachelor’s degree in political science from the University of Florida, and a master’s and PhD in international studies from the University of Miami.

Henrique Arevalo Poincot is a visiting fellow with the Atlantic Council’s Freedom and Prosperity Center. A strategy and communications specialist with expertise spanning Europe and Latin America, Arevalo Poincot is pursuing his master’s degree in democracy and governance at Georgetown University.

Related content

explore the program

The Freedom and Prosperity Center aims to increase the prosperity of the poor and marginalized in developing countries and to explore the nature of the relationship between freedom and prosperity in both developing and developed nations.

Civil Society

Democratic Transitions

Latin America

Political Reform

Politics & Diplomacy

Rule of Law

Image: Quito, Ecuador. ULAN/Pool / Latin America News Agency via Reuters Connect

Search

RECENT PRESS RELEASES

Related Post