A westward shift of heatwave hotspots caused by warming-enhanced land–air coupling

March 20, 2025

Abstract

Heatwaves pose serious risks to human health and lives, but how their occurrence patterns may change under global warming remains unclear. Here we reveal a systematic westward shift of heatwave hotspots across the northern mid-latitudes around the late 1990s. Both observational analysis and numerical simulation show that this shift is caused by intensified soil moisture–atmosphere coupling (SAC) in eastern Europe, Northeast Asia and western North America under recent background warming. The strengthened SAC shifted the atmospheric high-amplitude Rossby wavenumber-5 pattern westwards to a preferred phase position, which increased the probability of the occurrence of high-pressure ridges over these 3 hotspots by a factor of up to 39. Our results highlight the importance of SAC in shaping heatwave patterns and large-scale atmospheric circulation and challenge the conventional view that the land surface only passively responds to atmospheric forcing.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$29.99 /Â 30Â days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$209.00 per year

only $17.42 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Data availability

All data used in this study are freely accessible. The European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts reanalysis can be downloaded at https://cds.climate.copernicus.eu/cdsapp#!/search?text=ERA5%20back%20extension&type=dataset. The BEST data are freely available at http://berkeleyearth.org/data/. The GLEAM 4.1a can be obtained from https://www.gleam.eu/. CMIP6 data are available at https://aims2.llnl.gov/search/cmip6/. All GOGA and GOGA-PSM output used in this study can be obtained at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5800726 (ref. 70). The simulation data of Ctl and CtlpdLC are available on Zenodo at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14890985 (ref. 71).

Code availability

Analysis and figure generation were performed using Python3.8.18. The code used to set up model simulations, analyse data and create figures are available on Zenodo at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14890985 (ref. 71).

References

-

Christidis, N., Jones, G. S. & Stott, P. A. Dramatically increasing chance of extremely hot summers since the 2003 European heatwave. Nat. Clim. Change 5, 46–50 (2015).

-

Coumou, D. & Rahmstorf, S. A decade of weather extremes. Nat. Clim. Change 2, 491–496 (2012).

-

Lyon, B. & Dole, R. M. A diagnostic comparison of the 1980 and 1988 U.S. summer heat wave-droughts. J. Clim. 8, 1658–1675 (1995).

-

Namias, J. Anatomy of Great Plains protracted heat waves (especially the 1980 US summer drought). Mon. Weather Rev. 110, 824–838 (1982).

-

Smoyer, K. A comparative analysis of heat waves and associated mortality in St. Louis, Missouri—1980 and 1995. Int. J. Biometeorol. 42, 44–50 (1998).

-

Li, X. et al. Role of atmospheric resonance and land-atmosphere feedbacks as a precursor to the June 2021 Pacific Northwest heat dome event. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 121, e2315330121 (2024).

-

Philip, S. et al. Rapid attribution analysis of the extraordinary heat wave on the Pacific Coast of the US and Canada in June 2021. Earth Syst. Dyn. 13, 1689–1713 (2022).

-

Zhang, X. et al. Increased impact of heat domes on 2021-like heat extremes in North America under global warming. Nat. Commun. 14, 1690 (2023).

-

Lau, W. K. M. & Kim, K.-M. The 2010 Pakistan flood and Russian heat wave: teleconnection of hydrometeorological extremes. J. Hydrometeorol. 13, 392–403 (2012).

-

Liu, X., He, B., Guo, L., Huang, L. & Chen, D. Similarities and differences in the mechanisms causing the European summer heatwaves in 2003, 2010, and 2018. Earth’s Future 8, e2019EF001386 (2020).

-

Barriopedro, D., Fischer, E. M., Luterbacher, J., Trigo, R. M. & GarcÃa-Herrera, R. The hot summer of 2010: redrawing the temperature record map of Europe. Science 332, 220–224 (2011).

-

Ren, L., Zhou, T. & Zhang, W. Attribution of the record-breaking heat event over Northeast Asia in summer 2018: the role of circulation. Environ. Res. Lett. 15, 054018 (2020).

-

Sun, Y. et al. Global supply chains amplify economic costs of future extreme heat risk. Nature 627, 797–804 (2024).

-

Tuholske, C. et al. Global urban population exposure to extreme heat. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 118, e2024792118 (2021).

-

Chen, X., Cui, X. & Gao, J. Differentiated agricultural sensitivity and adaptability to rising temperatures across regions and sectors in China. J. Environ. Econ. Manage. 119, 102801 (2023).

-

Chen, M. et al. Rising vulnerability of compound risk inequality to ageing and extreme heatwave exposure in global cities. npj Urban Sustain. 3, 38 (2023).

-

Qin, M., Dai, A. & Zhang, R. A review of the Atlantic multidecadal variability. Adv. Earth Sci. (Chinese) 37, 963–978 (2022).

-

Dong, B. & Dai, A. The influence of the interdecadal Pacific oscillation on temperature and precipitation over the globe. Clim. Dyn. 45, 2667–2681 (2015).

-

Coumou, D., Petoukhov, V., Rahmstorf, S., Petri, S. & Schellnhuber, H. J. Quasi-resonant circulation regimes and hemispheric synchronization of extreme weather in boreal summer. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 111, 12331–12336 (2014).

-

Screen, J. A. & Simmonds, I. Amplified mid-latitude planetary waves favour particular regional weather extremes. Nat. Clim. Change 4, 704–709 (2014).

-

Lin, H., Mo, R. & Vitart, F. The 2021 western North American heatwave and its subseasonal predictions. Geophys. Res. Lett. 49, e2021GL097036 (2022).

-

Yu, B., Lin, H., Mo, R. & Li, G. A physical analysis of summertime North American heatwaves. Clim. Dyn. 61, 1551–1565 (2023).

-

Yang, X. et al. Phase-locked Rossby wave-4 pattern dominates the 2022-like concurrent heat extremes across the Northern Hemisphere. Geophys. Res. Lett. 51, e2023GL107106 (2024).

-

Lin, Q. & Yuan, J. Linkages between amplified quasi-stationary waves and humid heat extremes in Northern Hemisphere midlatitudes. J. Clim. 35, 8245–8258 (2022).

-

Kornhuber, K. et al. Amplified Rossby waves enhance risk of concurrent heatwaves in major breadbasket regions. Nat. Clim. Change 10, 48–53 (2019).

-

Wang, S. Y. S. et al. An intensified seasonal transition in the central U.S. that enhances summer drought. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 120, 8804–8816 (2015).

-

Zhang, P. et al. Abrupt shift to hotter and drier climate over inner East Asia beyond the tipping point. Science 370, 1095–1099 (2020).

-

Fischer, E. M., Seneviratne, S. I., Lüthi, D. & Schär, C. Contribution of land�atmosphere coupling to recent European summer heat waves. Geophys. Res. Lett. 34, L06707 (2007).

-

Seneviratne, S. I. et al. Investigating soil moisture–climate interactions in a changing climate: a review. Earth Sci. Rev. 99, 125–161 (2010).

-

Koster, R. D., Chang, Y., Wang, H. & Schubert, S. D. Impacts of local soil moisture anomalies on the atmospheric circulation and on remote surface meteorological fields during boreal summer: a comprehensive analysis over North America. J. Clim. 29, 7345–7364 (2016).

-

Miralles, D. G., Teuling, A. J., van Heerwaarden, C. C. & Vilà -Guerau de Arellano, J. Mega-heatwave temperatures due to combined soil desiccation and atmospheric heat accumulation. Nat. Geosci. 7, 345–349 (2014).

-

Miralles, D. G., van den Berg, M. J., Teuling, A. J. & de Jeu, R. A. M. Soil moisture-temperature coupling: a multiscale observational analysis. Geophys. Res. Lett. 39, L21707 (2012).

-

Xue, Y. et al. Spring land surface and subsurface temperature anomalies and subsequent downstream late spring-summer droughts/floods in North America and East Asia. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 123, 5001–5019 (2018).

-

Hotz, B., Papritz, L. & Röthlisberger, M. Understanding the vertical temperature structure of recent record-shattering heatwaves. Weather Clim. Dyn. 5, 323–343 (2024).

-

Knudsen, M. F., Jacobsen, B. H., Seidenkrantz, M. S. & Olsen, J. Evidence for external forcing of the Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation since termination of the Little Ice Age. Nat. Commun. 5, 3323 (2014).

-

Zhang, K., Zuo, Z., Suarez-Gutierrez, L. & Bu, L. The significant influence of the Atlantic multidecadal variability to the abrupt warming in Northeast Asia in the 1990s. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 7, 28 (2024).

-

Hong, X., Lu, R., Chen, S. & Li, S. The relationship between the North Atlantic Oscillation and the Silk Road pattern in summer. J. Clim. 35, 6691–6702 (2022).

-

Zhu, Y., Wang, H., Zhou, W. & Ma, J. Recent changes in the summer precipitation pattern in East China and the background circulation. Clim. Dyn. 36, 1463–1473 (2011).

-

Dai, A. Hydroclimatic trends during 1950–2018 over global land. Clim. Dyn. 56, 4027–4049 (2021).

-

Qiao, L. et al. Soil moisture–atmosphere coupling accelerates global warming. Nat. Commun. 14, 4908 (2023).

-

Mo, R., Lin, H. & Vitart, F. An anomalous warm-season trans-Pacific atmospheric river linked to the 2021 western North America heatwave. Commun. Earth Environ. 3, 127 (2022).

-

Dai, A. Increasing drought under global warming in observations and models. Nat. Clim. Change 3, 52–58 (2013).

-

Hsu, H. & Dirmeyer, P. A. Soil moisture-evaporation coupling shifts into new gears under increasing CO2. Nat. Commun. 14, 1162 (2023).

-

Ray, D., Ramankutty, N., Mueller, N., West, P. C. & Foley, J. A. Recent patterns of crop yield growth and stagnation. Nat. Commun. 3, 1293 (2012).

-

Puma, M. J., Bose, S., Chon, S. Y. & Cook, B. I. Assessing the evolving fragility of the global food system. Environ. Res. Lett. 10, 024007 (2015).

-

Bren d’Amour, C., Wenz, L., Kalkuhl, M., Christoph Steckel, J. & Creutzig, F. Teleconnected food supply shocks. Environ. Res. Lett. 11, 035007 (2016).

-

Schauberger, B. et al. Consistent negative response of US crops to high temperatures in observations and crop models. Nat. Commun. 8, 13931 (2017).

-

Sarhadi, A., AusÃn, M. C., Wiper, M. P., Touma, D. & Diffenbaugh, N. S. Multidimensional risk in a nonstationary climate: joint probability of increasingly severe warm and dry conditions. Sci. Adv. 4, eaau3487 (2018).

-

Vicedo-Cabrera, A. M. et al. The burden of heat-related mortality attributable to recent human-induced climate change. Nat. Clim. Change 11, 492–500 (2021).

-

Xi, D. et al. Risk factors associated with heatwave mortality in Chinese adults over 65 years. Nat. Med. 30, 1489–1498 (2024).

-

Hersbach, H. et al. The ERA5 global reanalysis. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 146, 1999–2049 (2020).

-

Rohde, R. & Hausfather, Z. The Berkeley Earth land/ocean temperature record. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 12, 3469–3479 (2020).

-

Miralles, D. G. et al. Global land-surface evaporation estimated from satellite-based observations. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 15, 453–469 (2011).

-

Kornhuber, K. et al. Extreme weather events in early summer 2018 connected by a recurrent hemispheric wave-7 pattern. Environ. Res. Lett. 14, 054002 (2019).

-

Hurrell, J. W. et al. A new sea surface temperature and sea ice boundary dataset for the community atmosphere model. J. Clim. 21, 5145–5153 (2008).

-

Hurk, B. V. D. et al. LS3MIP (v1.0) contribution to CMIP6: the Land Surface, Snow and Soil Moisture Model Intercomparison Project aims, setup and expected outcome. Geosci. Model Dev. 9, 2809–2832 (2016).

-

Qiao, L., Zuo, Z. & Xiao, D. Evaluation of soil moisture in CMIP6 simulations. J. Clim. 35, 779–800 (2021).

-

Lee, D. E., Ting, M., Vigaud, N., Kushnir, Y. & Barnston, A. G. Atlantic multidecadal variability as a modulator of precipitation variability in the southwest United States. J. Clim. 31, 5525–5542 (2018).

-

Bartusek, S., Kornhuber, K. & Ting, M. 2021 North American heatwave amplified by climate change-driven nonlinear interactions. Nat. Clim. Change 12, 1143–1150 (2022).

-

Rayner, N. A. et al. Global analyses of sea surface temperature, sea ice, and night marine air temperature since the late nineteenth century. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 108, 4407 (2003).

-

Eyring, V. et al. Overview of the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project Phase 6 (CMIP6) experimental design and organization. Geosci. Model Dev. 9, 1937–1958 (2016).

-

Priestley, C. H. B. & Taylor, R. J. On the assessment of surface heat flux and evaporation using large-scale parameters. Mon. Weather Rev. 100, 81–92 (1972).

-

Donges, J. F., Schleussner, C., Siegmund, J. F. & Donner, R. V. Event coincidence analysis for quantifying statistical interrelationships between event time series. Eur. Phys. J. Spec. Top. 225, 471–487 (2016).

-

Dai, A., Fyfe, J., Xie, S.-P. & Dai, X. Decadal modulation of global surface temperature by internal climate variability. Nat. Clim. Change 5, 555–559 (2015).

-

Xiao, D., Zhao, P. & Ren, H. Climatic factors contributing to interannual and interdecadal variations in the meridional displacement of the East Asian jet stream in boreal winter. Atmos. Res. 264, 105864 (2021).

-

Xiao, D., Li, J. & Zhao, P. Four�dimensional structures and physical process of the decadal abrupt changes of the northern extratropical ocean–atmosphere system in the 1980s. Int. J. Climatol. 32, 983–994 (2012).

-

Xiao, D. & Li, J. Spatial and temporal characteristics of the decadal abrupt changes of global atmosphere–ocean system in the 1970s. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 112, D24S22 (2007).

-

Peings, Y., Labe, Z. M. & Magnusdottir, G. Are 100 ensemble members enough to capture the remote atmospheric response to +2 °C Arctic sea ice loss? J. Clim. 34, 3751–3769 (2021).

-

Miller, R. G. Simultaneous Statistical Inference 2nd edn (Springer, 1981).

-

Bartusek, S. CAM5_GOGA_output. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5800726 (2021).

-

Zhang, K. Datasets and codes for ‘A westward shift of heatwave hotspots caused by warming-enhanced land-air coupling’. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14890985 (2025).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant number 42288101 to Z.Z.), National Key Research and Development Program (grant number 2022YFF0801703 to Z.Z.) and National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant number 42175053 to Z.Z.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K.Z. and Z.Z. wrote the initial manuscript. W.M., A.D. and R.Z. revised and improved the manuscript. K.Z. performed model analysis and generated the final figures. K.Z., Z.Z., A.D., R.Z. and W.M. contributed to the methodological design and interpretation of results.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Climate Change thanks Davide Faranda, Ruping Mo and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. 1 Comparison of phase position distributions of wave 5 with different amplitudes in Ctl (red) and CtlpdLC (blue) experiments.

a–h, The probability densities of the phase positions of wave 5 with amplitudes of (a) ≤−1.5 standard deviation (σ), (b) −1.5 – −1 standard deviation, (c) −1 – −0.5 standard deviation, (d) −0.5 – 0 standard deviation, (e) 0 – 0.5 standard deviation, (f) 0.5 – 1 standard deviation, (g) 1–1.5 standard deviation and (h) ≥ 1.5 standard deviation.

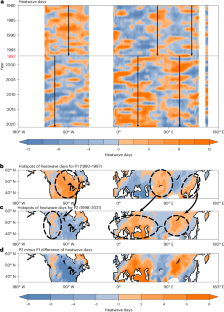

Extended Data Fig. 2 Development of surface soil moisture (SM), surface sensible heat flux (SH), and tropospheric atmospheric thickness (dZ) anomalies prior to continuous high-amplitude wave 5 events in the Ctl experiment.

a–e, The difference of the 3-days averaged surface soil moisture (Units: kg m-2; shading), surface sensible heat flux (Units: W m-2; hatching; only the regions with positive values were hatched) and the tropospheric atmospheric thickness (Units: m; contour; the difference of geopotential height between 200hPa and the bottom of the tropospheric atmosphere) anomalies between (a) 13–15 days and 16–18 days, (b) 10–12 days and 13–15 days, (c) 7–9 days and 10–12 days, (d) 4–6 days and 7–9 days, (e) 1–3 days and 4–6 days before the start day of continuous high-amplitude wave 5 events in the Ctl experiment. Basemaps from Natural Earth (https://www.naturalearthdata.com).

Extended Data Fig. 3 Development of surface air temperature (SAT) and tropospheric atmospheric thickness (dZ) anomalies prior to continuous high-amplitude wave 5 events in the Ctl experiment.

a–e, The difference of the 3-days averaged SAT (Units: K; shading), and the tropospheric atmospheric thickness (Units: m; contour; the difference of geopotential height between 200hPa and the bottom of the tropospheric atmosphere) anomalies between (a) 13–15 days and 16–18 days, (b) 10–12 days and 13–15 days, (c) 7–9 days and 10–12 days, (d) 4–6 days and 7–9 days, (e) 1–3 days and 4–6 days before the start day of continuous high-amplitude wave 5 events in the Ctl experiment. Basemaps from Natural Earth (https://www.naturalearthdata.com).

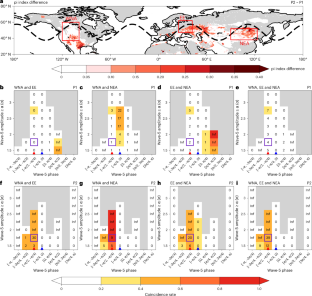

Extended Data Fig. 4 Distribution of northern hemisphere mid-latitude summer heatwave hotspots under different AMV and IPV phases in the near future (2025–2034) for the SSP1-2.6 scenario.

a, Scatter plot of AMV (x-axis) and IPV (y-axis) phases during 2025–2034 from 18 CMIP6 models under SSP1-2.6 scenarios. b–e, The distributions of the multi-model ensemble mean (MMEM) of summer heatwave days during 2025–2034 with the zonal mean of each year removed under the SSP1-2.6 scenario with models under (b) AMV+ and IPV+, (c) AMV+ and IPV-, (d) AMV- and IPV+ and (e) AMV- and IPV-. Basemaps in b–e from Natural Earth (https://www.naturalearthdata.com).

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figs. 1–12 and Table 1.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, K., Zuo, Z., Mei, W. et al. A westward shift of heatwave hotspots caused by warming-enhanced land–air coupling.

Nat. Clim. Chang. (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-025-02302-4

-

Received: 28 August 2024

-

Accepted: 28 February 2025

-

Published: 20 March 2025

-

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-025-02302-4

Search

RECENT PRESS RELEASES

Related Post