After a career as an environment writer, here’s what I have learned

November 28, 2025

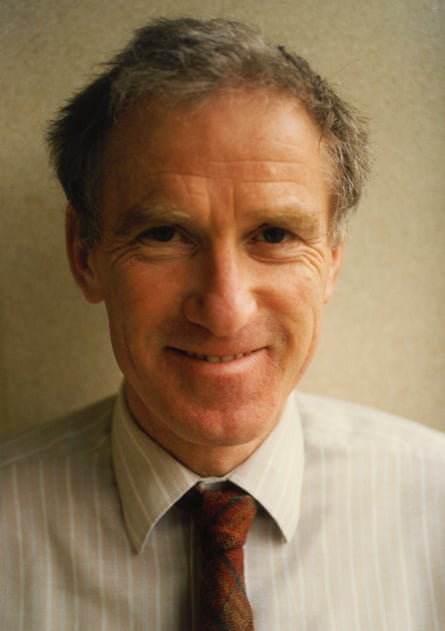

Paul Brown was the Guardian’s environment correspondent from 1989 until 2005 and has written many columns since. He submitted his last column last week after being diagnosed with terminal lung cancer. From his hospital bed in Luton, Paul offers his reflections on 45 years writing for the Guardian.

We, in the climate business, all owe a great deal to Mrs Margaret Thatcher. Her politics were anathema to me and to many Guardian readers. But she prided herself on being a scientist before she was a politician.

It was Thatcher’s inquiring mind that first demanded a scientific briefing about the dangers of the hole in the ozone layer, and subsequently on another even greater potential catastrophe, climate change. She was at the height of her influence on the international stage.

Meanwhile, the Guardian was getting more and more interested in the environment. Friends of the Earth and Greenpeace had grown into large radical campaigning organisations, alongside more established organisations like the WWF. Their young membership increasingly looked to the Guardian to report their activities and advertise green jobs.

As a general reporter on the paper, first assigned to cover nuclear power when the science editor was ill, I was allowed to sign on as a crew member of various Greenpeace ships. I went on voyages to block the Sellafield pipeline draining plutonium into the Irish Sea, I took trips round the coast highlighting sewage dumping and all manner of unlicensed chemical waste pipelines.

I began to report from international conferences trying to protect the seas and fish stocks, and best of all I spent three months in Antarctica on a Greenpeace boat that tried, and eventually succeeded, to get Antarctica accepted by the international community as a world park. In Antarctica, I got 26 pieces in the paper via satellite – the first journalist to file direct from the icy continent.

As I came back, Thatcher was in New York warning the UN about the dangers of climate change. Shortly afterwards, I found myself reporting from Geneva as Thatcher and other European leaders warned that the world was headed for disaster if it did not cut down on the use of fossil fuels.

Back in London, Peter Preston, the Guardian’s then editor-in-chief, who once encouraged me by saying you could not write about anywhere properly unless you have been there, called me into his office and made me environment correspondent. The Green party had got 16% in the European elections, and Thatcher thought they were a threat.

Sixteen years in the job followed. Most of the time, I sat beside John Vidal, who had an interest in everything. He took to editing the weekly environment pages, and then periodically dropping everything to head off after a maverick idea which generally turned into a brilliant story. More than once he left a note on my desk: “Could you do the pages this week, gone to Africa.”

It was clear from the beginning of my new job that Thatcher’s understanding of the science clashed with her ideology. Curbing the free market was not going to happen. Instead, she did what all politicians do – divert attention by creating something else. In this case, it was the Hadley Centre for Climate Prediction and Research, to study the subject better. The centre is now one of our world-renowned institutions.

But this pattern of politicians learning the inconvenient truths of climate change and then falling short in the actions required to solve the problem has continued ever since. In fact, with the recent advent of blatant climate deniers, it has got far worse.

In the 1990s, I travelled to a rollercoaster ride of international conferences. At the Earth summit in 1992 in Rio, Brazil, I saw George HW Bush and Fidel Castro walk past each other in the corridor, pretending they could not see each other. Oh, for a camera rather than a notebook!

That summit saw the setup of the climate change convention, the biodiversity convention and much else, although it failed to do enough to protect forests. The agreements set up in Rio de Janeiro sent me globe-trotting to various conferences of the parties (Cops) in capital cities around the world to report on the snail’s pace of progress on climate.

Back home in the 1990s, the UK was in recession. The Guardian news desk’s interest in the environment, once the Earth summit was over, was minimal. House repossessions and job losses were rightly more immediate and pressing.

But as the decade progressed, the Conservatives were ousted in 1997 and then, as John Prescott became environment secretary, the environment news kept moving up the agenda. By the time of the second Earth summit in Johannesburg in 2002, it was back at the top of the news list.

By the autumn of 2005, I was run off my feet. After the catastrophic foot and mouth epidemic, every department – home, foreign, city and features – wanted to know each day what story (or stories) I had for them. And every section naturally wanted their story first. Vidal had taught me one good lesson: that it was possible to get away with absences from your desk if you came back with a good story. At the same time, the Guardian Foundation and various UN institutions had adopted me as a tutor on environment matters and began sending me to eastern Europe and Asia to teach other journalists how to cover this subject. By 2005, the pressure of work became too great and I took redundancy. Six months after I left, the Guardian had five people doing my old job.

I have spent the 20 years since writing about climate change and related matters for a huge variety of publications – including hundreds of Weatherwatch and Specieswatch columns for the Guardian. I have attended more conferences, such as the Cops in Paris and Warsaw, and helped train young journalists on how to cover these bewildering events, giving something back to the profession that has given me so much.

But I have also watched in continuing dismay what we might call the Thatcher syndrome: apparently intelligent politicians failing yet and yet again to have the courage to implement the decisions necessary to tackle the ever more imminent danger of climate change. Of course, as at the recent Cop30 in Brazil, they have been beset by more fossil fuel lobbyists than environmentalists, a phenomenon that was first reported by Vidal and I in the 1990s. Do the well-funded fossil fuel lobbyists always have to win?

And there has been another – in my view, very sinister – development, which has put back the cause of action on climate change into very dangerous territory: the latest “nuclear renaissance”. I started covering the nuclear industry in the early 1980s, and like all well trained journalists was neutral then. Nuclear power was a success story because it was part of the National Coal Board and its true costs were hidden, not just from consumers but from the government.

The first nuclear renaissance took place in the late 1980s when the Sizewell B nuclear power station was being built. Several more were on the drawing board, but Thatcher demanded to know the cost and the resultant price of electricity to consumers, and was so enraged that she and the government had been lied to about the real cost that she cancelled the rest of the programme. It was one of my more memorable stories.

At least two more “renaissance” moments have come and gone, mostly also on cost grounds, but now Keir Starmer’s government has gone completely gung-ho on nuclear – to the utter dismay of many environmental campaigners.

The government subsidies are simply huge: a nuclear tax is being levied on hard pressed consumers. What is the government thinking of? The fossil fuel industry, which has thrown its weight behind nuclear power, is of course delighted; all these decades of new construction without any electricity to show for it gives at least another decade or two of unabated burning gas. It is no accident that Centrica invested in Sizewell C – after all, it is primarily a gas company. With Sizewell C likely to take 10 to 15 years to build, that is a lot of extra gas being burned and profits for shareholders.

But the biggest mystery is small modular reactors (SMRs), which are theoretically built in factories and put together on site, making them easier and cheaper to build. SMRs originally were defined as generating less than 300MW, about a third of the size of a traditional nuclear or gas station, but have now been redefined by Rolls-Royce to mean 470MW because even on the drawing board the company could not make the economics work.

Several have been promised, but the problem is that they do not yet exist, except on paper or on a computer. No factory has been built to make their components, no prototype has been built, no licensing process has taken place. All that is known about them is that (also on paper) they produce more hotter waste at the end of their lives.

I know many of my colleagues at the Guardian would disagree, but as I disappear into oblivion after 40 years of covering this industry, I would ask them to keep looking at it closely. Over the years I have regularly been fed wildly optimistic figures of construction costs and times and of the resultant electricity supply. At worst we have been consistently lied to. Unlike wind and solar, nuclear costs have consistently gone up for decades.

And now it is happening all over again at Sizewell C in Suffolk and in north Wales; the British public is being forced to watch as the government pours billions of pounds of our money down the drain. Journalists should be exposing this terrible waste. In the name of the climate I ask them to look closely at the real facts, not believe the hype, and try to stop this waste of resources before it gets worse.

Search

RECENT PRESS RELEASES

Related Post