Banknotes, bitcoin and the battle for value

January 29, 2026

For most of human history, money could be touched, and trade was a face-to-face activity. Trust was personal and banking was physical, with money moving only as fast as people or ships could carry it.

From around 3000BC in Mesopotamia, accounts, debts and obligations among traders began to be tracked via inscriptions on clay tablets.

Then came the emergence of coinage, first minted in Lydia in modern-day Turkey around 650BC, standardising value and reducing trade friction.

Paper money, which has its roots in the promissory notes of Carthage, China and the Roman empire, was first issued as official currency by China’s Song dynasty in the 11th century, with Europe’s first paper currency issued in Sweden in the 17th century.

Circulation of the new medium of currency was initially slow, however, and remained geographically narrow.

Such limits were addressed in the late 19th century, when currencies became tied to gold, stabilising exchange rates and allowing for the wider circulation of national currencies.

Yet the first world war saw the era of the gold standard come to an abrupt end, in favour of government-driven money supply expansions that enabled countries to finance government spending, all too often leading to rampant inflation.

Stability returned following the Bretton Woods conference of 1944, when currencies were pegged to the dollar, itself convertible to gold. By 1971, the link between the dollar and gold was finally severed, with the currency floating freely ever since.

While all national currencies are now fiat-backed, with trust in the issuing government standing in for gold, old perceptions die hard, says Seamus Rocca, chief executive of Xapo Bank.

“People still had this perception [even five years ago] that their currency was backed by gold. Most people didn’t understand that in [the 1970s] that actually stopped, and governments made a conscious decision to be able to print more money because they didn’t have enough gold,” Rocca says.

There is a growing realisation, however, that currency has value “because we all say that it does”, he adds.

That is not to say commodities, sometimes unusual ones, do not still have their place. In Italy, where parmesan has changed hands since the Middle Ages, cheese can still be used as collateral.

Credito Emiliano, a bank in Italy’s Emilia Romagna region, reportedly holds about 430,000 wheels of parmesan, reportedly worth around €190mn, which can still be accepted as collateral for loans to help finance cheese makers.

The bank’s cheese reserves are a reminder of money’s tangible foundations, providing a counterbalance to the rapid digitalisation of money of the past 70 years.

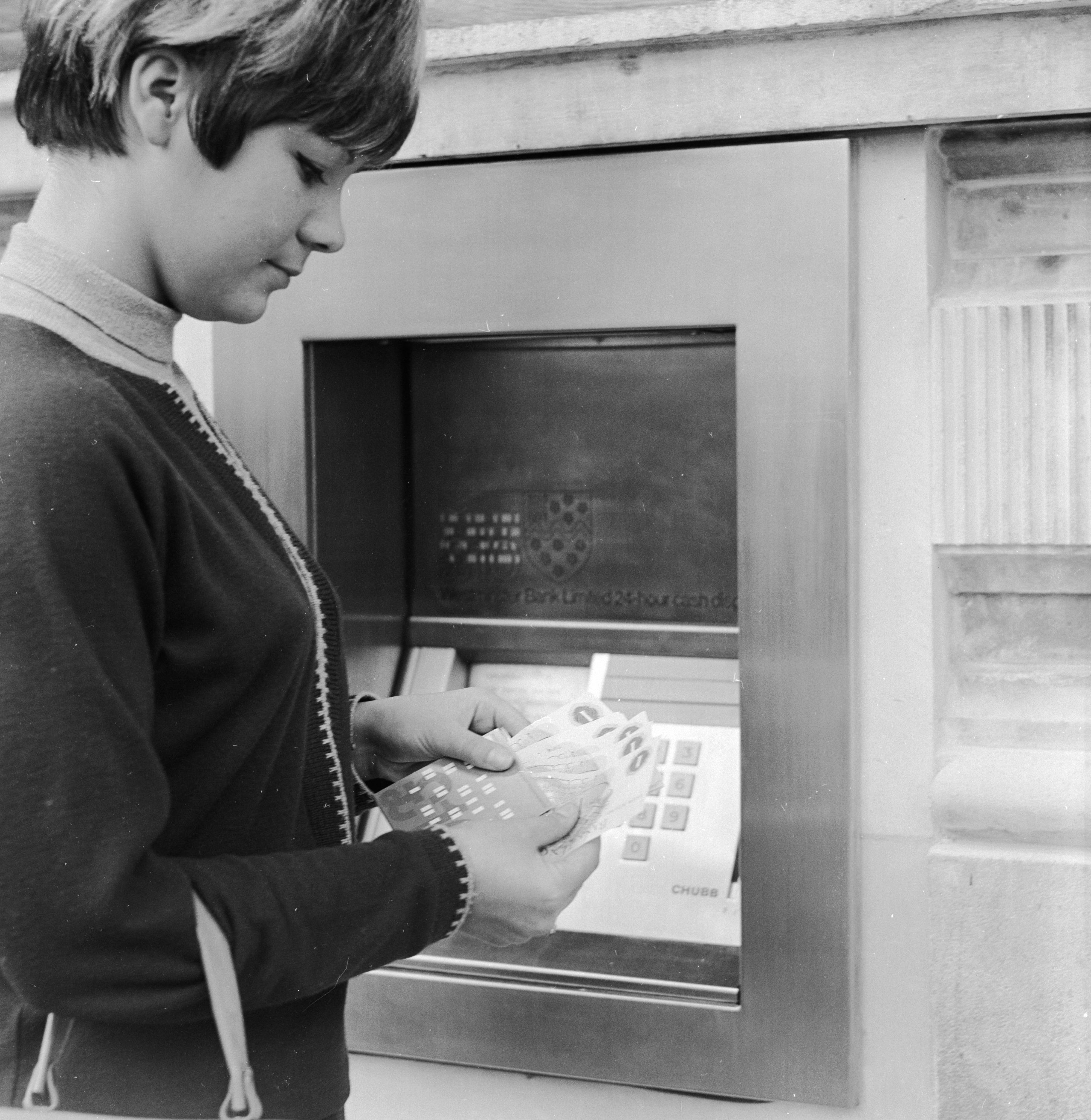

Banks began experimenting with computers in the 1950s, and would go on to replace paper ledgers with electronic records from the 1970s. Around this time, ATMs and payment cards began to proliferate.

Then came online banking, which, by the early 2000s, saw consumers increasingly pay bills and manage accounts with reduced human interaction.

By 2024, 42 per cent of adults in low- and middle-income countries made an in-store or online digital merchant payment, up from 35 per cent in 2021, according to the World Bank.

Digitalisation has seen bank branch numbers fall sharply, in Europe and North America in particular. Since 2008, the total number of EU branches has dropped by 42.4 per cent, with Spain, Germany and Italy noting the greatest contractions, according to European Central Bank data.

But just as digital trust took hold, the 2008 financial crisis dented consumers’ faith in banks.

That same year, in a key milestone for new types of money, an anonymous creator under the name Satoshi Nakamoto published a proposal for a peer-to-peer electronic cash system that bypassed financial intermediaries.

Bitcoin launched shortly afterwards in January 2009, with a fiercely independent ideology at its very core. The cryptocurrency’s “genesis block”, the opening entry on its blockchain digital ledger, made a pointed reference to the bank bailouts of the financial crisis under way at the time.

Digital finance by that time was nothing new, given the global rise of online and mobile banking. Bitcoin’s key innovation, however, was that it was not backed by a national government, and operated off traditional financial rails.

Still, it took some years for interest in the new currency, and others like ether and sol that would spring up in its wake, to grow beyond crypto-native circles.

Lars Seier Christensen, who co-founded Saxo Bank in 1992 and kept an eye on blockchain technology from 2011, saw the “missed opportunity” that passed by many banks, including his own.

“I [saw] some of the pain points we had in the bank, where I was still CEO . . . I just saw this could potentially solve a lot of these [issues]. I was quite enthused about it,” Christensen says.

At the time, as chief executive, Christensen had many discussions with the bank’s legal and compliance teams, who, in the absence of regulatory clarity, were not in favour of exploring it.

“Even as the CEO, I could not really get crypto into my own bank. That’s a shame, because we would have been by far the first bank in the world to facilitate ethereum and bitcoin,” he says.

Christensen was one of very few bankers who attended related conferences early on, where he felt the blockchain-native groups saw him as some kind of “endorsement from the establishment”.

Bitcoin’s price rise has since become one of the biggest stories in finance of the past 10 years, peaking at more than $126,000 in October 2025. Though weakened by tightening monetary policy and fraud scandals along the way, bitcoin’s market cap today is nearly $2tn, even though it remains a largely speculative asset rather than a payments instrument.

“That’s the interesting bit about the future of money: what is that money backed by? It is essentially backed by a government . . . if I don’t trust the government, I don’t like the government in power, I don’t like their views, what are [the] alternatives? . . . Gold or bitcoin,” Rocca says.

“Look at the price of gold hitting record highs, and the price of bitcoin hitting record highs. I don’t think that’s an accident.”

While bitcoin use as a mainstream currency remains a distant prospect, a more likely candidate has emerged in recent years in the form of stablecoins.

Stablecoins, digital currencies that are backed by tangible assets such as gold and fiat currencies, emerged in 2014 as a method for crypto traders to move funds between different tokens. Proponents quickly made the case for their use in traditional finance, particularly cross-border payments.

Initially viewed with hostility by the mainstream — Facebook’s early stablecoin offering libra in 2019 was quickly shot down by regulators — interest has surged in recent years amid rising bitcoin prices and enthusiastic backing by US President Donald Trump’s second administration.

Banks watched closely even as they stayed largely on the sidelines early on. Regulators have moved to clarify the asset class, some more quickly than others.

The Bank for International Settlements warned last June that stablecoins fail to meet the criteria for sound money and are unlikely to play a central role in the financial system of the future.

But jurisdictions including the US, the EU, Singapore and the UAE have all moved to regulate the asset class, followed — albeit slowly — by the UK.

In November, the Bank of England set out new proposals for regulating stablecoins. The proposed framework aims to integrate the digital currencies into the UK’s payments system and is part of its wider stablecoin regime, which is set to be implemented later this year.

The FCA established a dedicated testing environment that same month for prospective stablecoin providers, with a view to participants being able to begin issuing the digital assets from as early as April.

“If you want stablecoins to grow in the UK, and you want sterling to have a role in the on-chain market of the future, you need to make sure you create rules that allow it to grow,” says Keith Grose, UK chief executive of Coinbase.

“I expect over the next 12 to 24 months in the UK, as these regulations roll out, more and more large financial institutions, consumer-facing financial institutions, will start to release crypto trading or crypto ETN products of some type. We’re seeing a lot of interest there . . . as regulation and the rules become clear, competition will grow.”

Banks don’t want to be left behind, of course. Revolut — which is still without a full UK banking licence but remains Europe’s largest neobank — dominates the UK’s crypto exposure.

In November, the fintech received a Mica licence (see Provision Tracker) in a move which could spur other regional neobanks and fintechs to seek EU crypto approval.

Mica underpins Revolut’s crypto expansion plans which began nearly a decade ago when the fintech introduced crypto trading within its app. It is now one of the first major fintechs licensed to offer crypto asset services across Europe.

Like many others, Wise is taking stock of Revolut’s moves. The money transfer firm is set to explore how to enable customers to use cryptocurrencies on its platforms as part of plans to expand its digital assets offering globally, after its first significant push into the sector last year.

Among incumbents, Standard Chartered Luxembourg filed for a Mica licence last year, in a move that would see it become one of the first UK-headquartered banks with Mica approval for a European subsidiary.

Other lenders are also pushing ahead. In September, nine European banks including UniCredit and ING unveiled plans to jointly launch a euro-backed stablecoin to boost the region’s payments autonomy and reduce reliance on dollar-denominated stablecoins. BNP Paribas and DZ Bank have since joined the group.

There must be “room” for US banks to join the consortium too, ING previously told The Banker.

JPMorgan opted not to issue a stablecoin because its deposit token is itself an optimal way to bring cash products to institutional customers.

The US lender launched JPM Coin, a tokenised deposit reflecting customer deposits on a public ledger, in November. It expects volumes of the coin to grow to around $10bn within three to five years.

In the meantime, UK banks are working quietly behind the scenes, Grose says.

“[They] are building out teams, and they’re making plans, and we’re talking to a lot of them. You haven’t seen them in the market yet, but they’re actively under development. Partnerships are being signed, and . . . competition is going to increase,” he adds.

As interest in cryptocurrencies grows, for example by enabling consumers to hold bitcoin and using stablecoins for cross-border trade, this year could see more banks moving from the sidelines into large-scale adoption.

The race continues.

Search

RECENT PRESS RELEASES

Related Post