Beijing row highlights need for Japan to reduce cleantech dependence on China

January 18, 2026

Since the Fukushima nuclear disaster, Japan has been one of the world leaders in solar. Today, despite limited flat, open space, it gets about 10% of its electricity from solar panels — more than France, the United States, and, perhaps most surprisingly, China.

But this solar might has mostly been generated using imported panels, as Japan has nearly no domestic production of photovoltaics (PV), despite it being a technology that Japan pioneered.

Japan’s ambitious climate and energy goals, including its Paris Agreement target to cut emissions by 60% by 2035 compared with 2013 levels and its plan — announced in 2021 — to achieve net-zero emissions by 2050, will require a massive expansion of domestic renewable energy production, especially solar, but also wind and battery storage.

But there’s a problem — those technologies are dominated by China, and Japan’s history shows that economic dependence on China comes with risks.

“China has shown it is willing to use the business side for what the United States calls economic coercion,” said Yuriy Humber, the founder of Japan NRG, a Tokyo-based energy intelligence company. “China could, if it wanted, impose restrictions on the exports of other technologies, cleantech included, which could affect solar panels and batteries.”

Japan, which faced the wrath of China blocking exports of rare earth minerals back in 2010, a situation that is repeating itself in 2026 over Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi’s comments about a potential military response in a Taiwan contingency, has become increasingly wary of relying on China. The Takaichi administration has also come out with new policies against megasolar while showing enthusiastic support for nuclear power. As part of this, Tokyo has expanded state support for alternative decarbonization technologies with questionable efficacy — including carbon capture and sequestration (CCS), ammonia and liquefied natural gas (LNG).

The concern is that Japan might not only fail to meet its own decarbonization goals but also see its energy and automotive industries lose out to the Chinese cleantech industry as countries around the world shift away from internal combustion vehicles and fossil fuel power generation.

Behind China’s rise

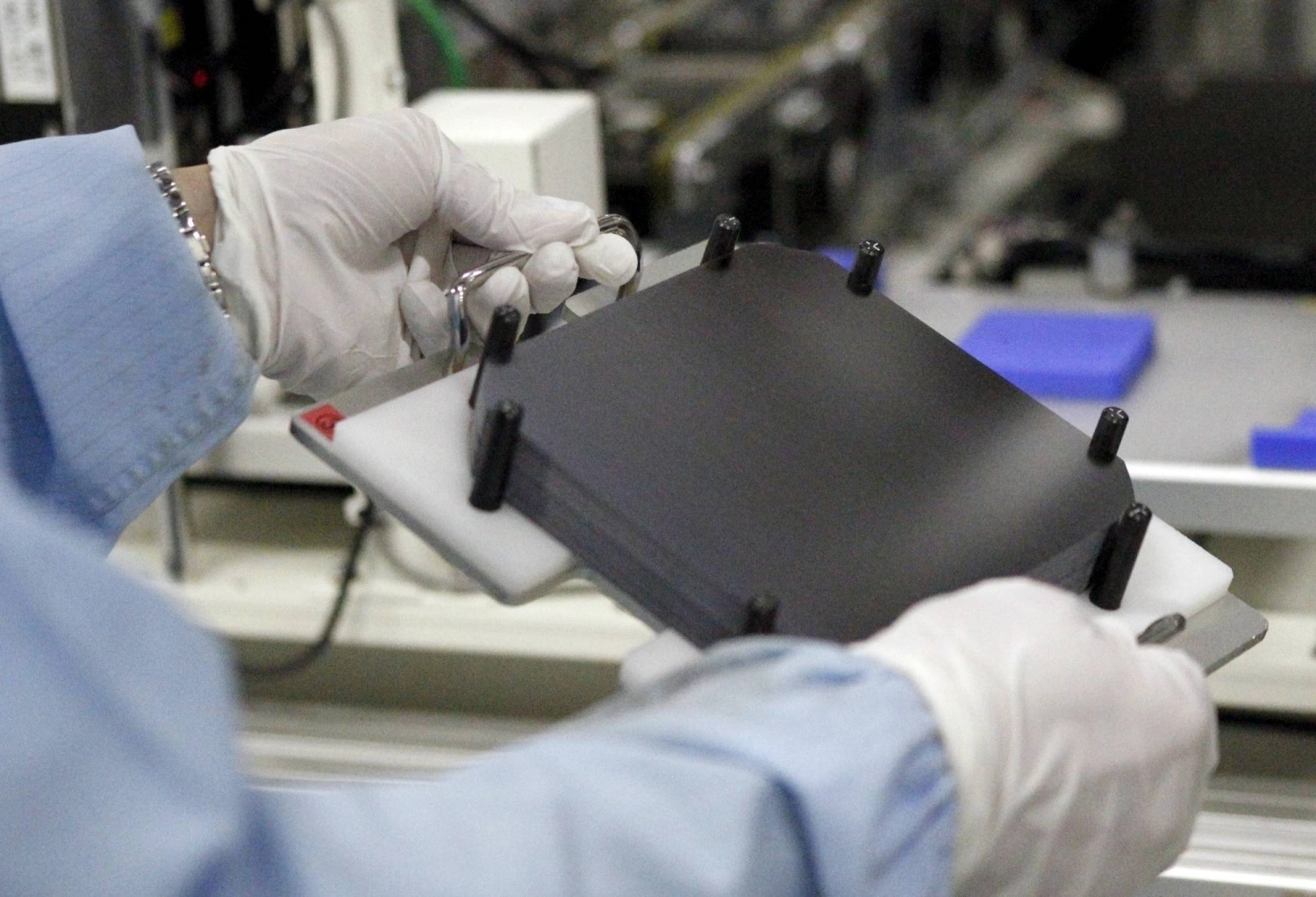

It was not so long ago that the world’s leading exporter of solar panels was, in fact, Japan. At the time, Japanese companies, including Sharp and Kyocera, were manufacturing and exporting solar panels from factories in Katsuragi, Nara Prefecture, and Sakai, Osaka Prefecture, to countries such as Germany and the United States.

“Japan once led in solar panel production until the early 2000s,” said Hiroshi Ohta, a professor and energy expert at Waseda University. “But companies lost the market to China.”

Today, Japan has limited solar manufacturing capacity, relying on imports for more than 90% of installed solar panels in 2024. Sharp and Kyocera, once leading global producers, are now not even ranked in the top 10 globally. A similar dynamic took place with solar manufacturers in other countries, like Germany and the U.S. The undisputed world leader is now China, which produces more than 80% of solar panels and components, and has near total control of key solar, battery, and wind turbine components, such as solar-grade polysilicon, silicon wafers and modules.

“Because of cheap labor costs and other factors, China could produce inexpensive solar panels and could export and kill Japan, Germany and U.S. production,” Ohta said.

Low prices, state subsidies, and access to cheap inputs made it difficult for solar manufacturers in Europe, Japan, South Korea and the U.S. to compete on price. While there are still solar manufacturers in the U.S. and South Korea, they benefit from state support that, in Japan, has mostly been reserved for traditional energy sources such as LNG.

“For China, it was about gaining technological advantage in the next generation of tech and gaining business advantage as well as global influence and political leverage, with cleantech as a side benefit,” said Humber.

Social and human rights risks

While some climate advocates see China’s excess solar, electric vehicle and cleantech capacity — and growing power as an exporter — as a good thing for global decarbonization, others raise concerns about security and social impacts.

“The idea that China’s clean technology successes have uncovered a more hopeful recipe for climate salvation is wrong,” said Seaver Wang, who leads the energy team at the Breakthrough Institute, a U.S.-based think tank.

Wang and others point to the clear links that solar, wind and other Chinese technologies have to the Xinjiang region, the homeland of the Uyghurs, who the Group of Seven nations say have been subject to wide-ranging human rights abuses. In May 2025, a report from the Japan Uyghur Association and the Tokyo-based nonprofit Human Rights Now identified numerous brands — including Japanese giants Marubeni, Mitsubishi Electric and Panasonic — as having indirectly sourced from suppliers in the region. Numerous reports have also shown the global reach of Xinjiang’s products, including in the areas of cleantech, particularly the solar supply chain.

“Allegations of state-sponsored Uyghur forced labor program participation have plagued solar polysilicon, metallurgical silicon and aluminum production in Xinjiang,” said Wang.

It’s not just in Xinjiang — Chinese sourcing of minerals from countries such as Indonesia, Myanmar and the Democratic Republic of the Congo has been linked to labor and human rights abuses. Often, these are regions where — due to instability or sanctions — Japanese and Western companies are unable to operate.

“Globally, many unethical supply chains leverage China as their chief refuge from accountability,” Wang added.

There are growing efforts by governments to scrutinize supply chains and restrict imports from China due to these concerns. The most direct instance was the passage of the Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act (UFLPA) in the U.S. The bill, which came into force in 2022, prohibits the import of all goods from the Xinjiang region due to concerns about complicity in state-sanctioned forced labor.

The European Union has been considering an even broader set of rules, the Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive, that would also impact Chinese cleantech imports and add scrutiny to mining supply chains in other source countries. France, Germany, Canada and Mexico have also recently expanded national human rights due diligence requirements, which Johannes Blankenbach, the senior Europe researcher at the Business and Human Rights Center, sees as part of a global trend.

“Over the last couple of years, there has been a trend towards mandatory rules,” said Blankenbach. “I’m hopeful that the trend towards mandatory is here to stay and continues in other parts of the world.”

While Japan has yet to pass its own, there has been a push from the government to get companies to adopt stricter voluntary guidelines. In parliament, the cross-party Japan Uyghur Parliamentary Association has begun discussions on drafting a UFLPA-like law for Japan. Moreover, with Europe and the U.S. as major markets for Japanese exports, regulations there could have an impact on Japanese supply chain management too.

The nonprofit World Benchmarking Alliance argued in a statement released last year in favor of a mandatory human rights due diligence law, noting that “Japanese companies struggle to extend due diligence … into complex global supply chains, which is critical for meeting international expectations and maintaining competitiveness in global markets.”

In the U.S., fewer imports of solar panels tainted by forced labor and increased tariffs on Chinese solar products hasn’t slowed down the expansion of solar due to increased domestic production, partly as a result of increased state support through initiatives such as former U.S. President Joe Biden’s Inflation Reduction Act and imports from other countries such as South Korea and Malaysia. Japan hasn’t yet made similar moves, with state support mostly going to fossil fuel technologies, but the recent push to support next-generation perovskite solar cells — which are thinner, more flexible and could be produced domestically without reliance on Chinese inputs, but do come with questions over durability and price — might be a sign of a shift in thinking.

“With perovskite, Japan has been quite secretive,” said Humber. “The number of companies involved has been somewhat limited, and state support has been very tight, partly to prevent technology know-how from being leaked.”

Diversifying the energy transition

Japan’s companies have, for now, a strategic advantage in certain energy technologies such as gas turbines, said Humber. Japan has also pushed technologies such as CCS and ammonia co-firing through government-led efforts such as the Asia Energy Transition Initiative. And while there are pilot projects to expand CCS and co-firing in places such as Indonesia, Thailand and Malaysia, there isn’t yet a proven business model for those technologies, and many analysts are skeptical there ever will be.

But Southeast Asia does present an opportunity when it comes to proven cleantech, as countries in the region are also expressing concern about China’s dominance in the sector and its dumping of excess solar onto developing countries. There are also concerns about China’s perceived reluctance to share that technology, which would allow other countries to expand their cleantech sectors.

Japan’s investment in alternative cleantech supply chains, perhaps with partners such as India, who also fear Chinese economic coercion, could be a way to reduce fears of Chinese dependence while also expanding Japan’s role in this growing sector.

“There has to be diversification of supply chains,” said Humber. “You may not be able to achieve 100% diversification or find a supplier as big as China, but you should certainly try to build up capacities domestically and elsewhere.”

Search

RECENT PRESS RELEASES

Related Post