Beyond Boundaries: Rethinking Conservation in the Age of Environmental Crime

October 7, 2025

Organized crime is rewriting the rules of conservation and exposing why protecting land on paper means little without dismantling the profits driving environmental destruction.

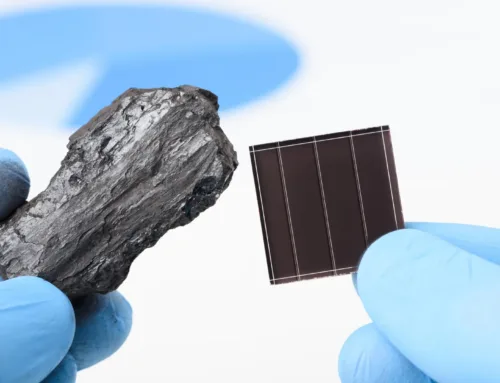

Conservation once meant lines on a map: a park proclaimed, a forest reserve outlined, a promise inked on paper that the wild would endure. But in our age, those lines bleed and blur. Environmental crime has ballooned into a multibillion-dollar global enterprise from illegal logging to wildlife trafficking, now valued at up to USD 281 billion annually and growing nearly three times as fast as the legitimate economy.

The problem is not confined to one region – it is global. In the Amazon, illegal mining and logging penetrate Indigenous territories and protected areas, bringing violence and environmental contamination in their wake. In Borneo, vast tracts of rainforest are cleared for palm oil and timber, often through “shadow companies” that obscure their true owners as commodities flow into global markets. And in the Congo Basin, illegal logging and charcoal production have surged in rebel-controlled areas, threatening endangered gorillas and further destabilizing forest ecosystems.

Across these rainforest frontlines, environmental crimes are now central to organized crime, driving deforestation, corruption, and illicit wealth. Among them, the illegal wildlife trade has surged into a multibillion-dollar market, threatening thousands of species. Between 2015 and 2021, nearly 13 million illicit wildlife products were seized, representing only a fraction of the true scale of the trade.

Nowhere is this convergence of profit and violence clearer than in Colombia. As gold prices reached record highs this year, armed groups tightened their grip on mining corridors, financing conflict while accelerating deforestation and poisoning rivers with mercury. Illegal gold mining has become a central financial engine of organized crime as the price of cocaine has plateaued, forcing traffickers to move more product for the same revenue. Entire communities have been devastated, and Indigenous leaders who resist often pay with their lives. Meanwhile, investigations by Colombia’s Attorney General’s Office, echoed in subsequent media reporting, suggest that three of Colombia’s top gold exporters have been deeply entangled in laundering schemes tied to illegal mining, allegedly funnelling billions of dollars’ worth of illicit gold into the legal supply chain.

Yet conservation is still too often measured in hectares of “protected” land. Governments and donors can point to neat statistics, but counting hectares alone does not address the incentives driving destruction. Protected areas matter, but they mean little if the financial drivers of crime remain. Tackling those incentives is harder to measure, yet every bit as vital.

The limits of the current approach are not abstract. The human toll is stark. At least 196 land and environmental defenders were killed in 2023 for trying to protect their homes, communities, or the planet, bringing the global total since 2012 to more than 2,100 killings. Once again, Latin America was the deadliest region in the world, with 166 killings overall; 54 in Mexico and Central America and 112 in South America. Their courage underscores a hard truth: to defend nature today is to confront organized crime.

There have been glimmers of progress. Satellites and drones now allow real-time monitoring of deforestation. Forensic labs trace ivory DNA or timber chemistry back to origin. International bodies like INTERPOL and the UN Office on Drugs and Crime are building task forces, and conservation institutions are treating organized environmental crime as a central global threat. Brazil’s mid-2000s crackdown showed what is possible when technology, policing, and financial penalties are combined, cutting deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon by three-quarters.

But today’s adversaries are also getting more sophisticated. They embed in global finance, route commodities through multi-jurisdictional corporate chains, and exploit secrecy to sanitize profits. Shut down one illegal mine, and capital reappears upriver. Seize one timber shipment, and traffickers reroute the next. Every loophole becomes an invitation. The conservation community needs to accept that boundaries on maps do not make ecosystems safe; only by dismantling the financial incentives behind environmental crime can protection on paper become preservation in practice.

To curb these incentives, we need stronger beneficial ownership transparency rules to address shell companies, tougher anti–money laundering oversight, and more rigorous due diligence on risky commodities. Just as important are investments in law enforcement and judicial capacity, so that financial crimes are not only traced but prosecuted. By closing loopholes and following the money, conservation can deny traffickers the profits that make environmental destruction attractive. This is also a U.S. problem. Illicit gold and other dirty commodities are already entering U.S. markets, laundered through shell companies and weak customs controls. Unless policymakers act, these loopholes will continue to fuel crime abroad while undermining U.S. security and financial integrity.

To truly protect nature now means more than drawing boundaries – it means fortifying them against financial and criminal pressure. We must measure success not merely in square kilometers but also in the dismantling of illegal economies, the protection of environmental defenders, and the denial of safe passage to illicit profits of destruction. The old conservation story of hectares tallied and maps inked has passed.

The new story demands we look past the boundary to the balance sheet. From Colombia’s mercury-choked rivers to the Congo Basin’s dwindling forests and Borneo’s palm oil frontiers, the pattern is clear: organized syndicates have diversified into nature, turning ecosystems into profit streams. Conservation must now confront the financial engines of destruction that operate across continents. Only then will protected areas be truly safe.

Search

RECENT PRESS RELEASES

Related Post