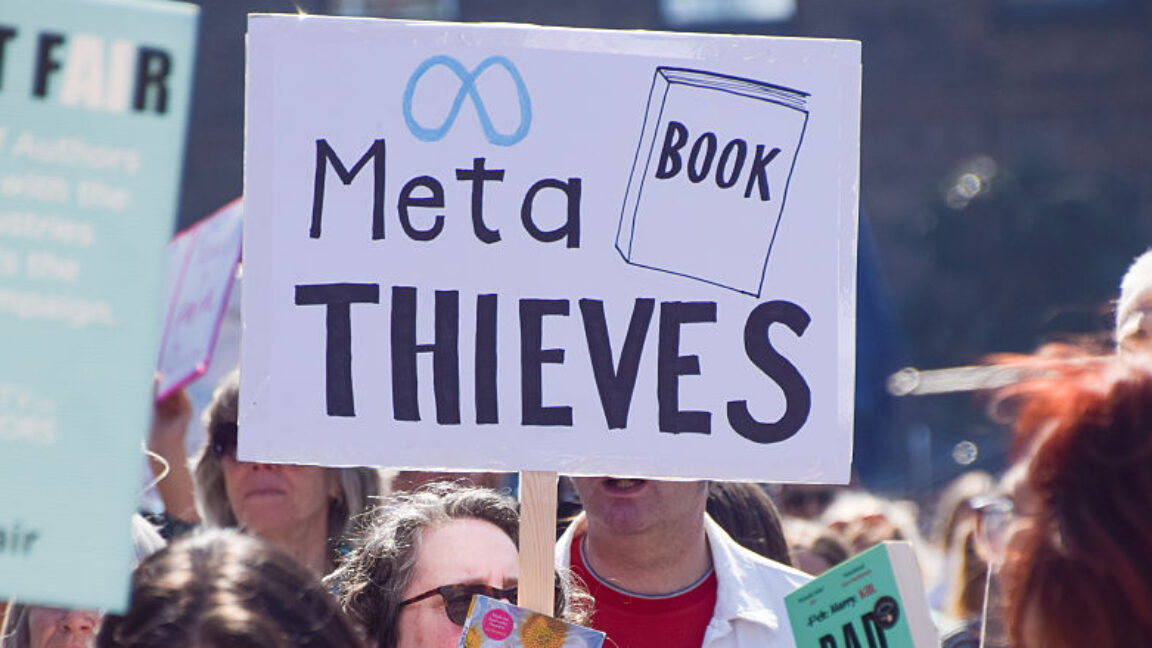

Book authors made the wrong arguments in Meta AI training case, judge says

June 26, 2025

Judges clash over “schoolchildren” analogy in key AI training rulings.

Soon after a landmark ruling deemed that when Anthropic copied books to train artificial intelligence models, it was a “transformative” fair use, another judge has arrived at the same conclusion in a case pitting book authors against Meta.

But that doesn’t necessarily mean the judges are completely in agreement, and that could soon become a problem for not just Meta, but other big AI companies celebrating the pair of wins this week.

On Wednesday, Judge Vince Chhabria explained that he sided with Meta, despite his better judgment, mainly because the authors made all the wrong arguments in their case against Meta.

“This ruling does not stand for the proposition that Meta’s use of copyrighted materials to train its language models is lawful,” Chhabria wrote. “It stands only for the proposition that these plaintiffs made the wrong arguments and failed to develop a record in support of the right one.”

Rather than argue that Meta’s Llama AI models risked rapidly flooding their markets with competing AI-generated books that could indirectly harm sales, authors fatally only argued “that users of Llama can reproduce text from their books, and that Meta’s copying harmed the market for licensing copyrighted materials to companies for AI training.”

Because Chhabria found both of these theories “flawed”—the former because Llama cannot produce long excerpts of works, even with adversarial prompting, and the latter because authors are not entitled to monopolize the market for licensing books for AI training—he said he had no choice but to grant Meta’s request for summary judgment.

Ultimately, because authors introduced no evidence that Meta’s AI threatened to dilute their markets, Chhabria ruled that Meta did enough to overcome authors’ other arguments regarding alleged harms by simply providing “its own expert testimony explaining that Llama 3’s release did not have any discernible effect on the plaintiffs’ sales.”

Chhabria seemed to criticize authors for raising a “half-hearted” defense of their works, noting that his opinion “may be in significant tension with reality,” where it seems “possible, even likely, that Llama will harm the book sale market.”

There is perhaps a silver lining for other book authors in this ruling, Chhabria suggested. Since Meta’s request for summary judgment came before class certification in the lawsuit, his ruling only applies to the 13 authors who sued Meta in this particular case. That means that other authors who perhaps could make a stronger case alleging market harms could still have a strong chance at winning a future Meta lawsuit, Chhabria wrote.

“In cases involving uses like Meta’s, it seems like the plaintiffs will often win, at least where those cases have better-developed records on the market effects of the defendant’s use,” Chhabria wrote. “No matter how transformative [AI] training may be, it’s hard to imagine that it can be fair use to use copyrighted books to develop a tool to make billions or trillions of dollars while enabling the creation of a potentially endless stream of competing works that could significantly harm the market for those books.”

Further, Chhabria suggested that “some cases might present even stronger arguments against fair use”—such as news organizations suing OpenAI over allegedly infringing ChatGPT outputs that could indirectly compete with their websites. Celebrating the ruling, a lawyer representing The New York Times in that suit, Ian Crosby, told Ars that both Chhabria’s and Alsup’s rulings are viewed as strengthening the NYT’s case.

“These two decisions show what we have long argued: generative AI developers may not build products by copying stolen news content, particularly where that content is taken by wrongful means and their products output substitutive content that threatens the market for original, human-made journalism,” Crosby said.

On the other hand, Chhabria wrote that AI companies may have an easier time defeating copyright claims if the feared market dilution is a trade-off for a clear public benefit, like advancing non-commercial research into national security or medicine.

Chhabria said that if the authors had introduced any evidence of market dilution, Meta would not have won at this stage of the case and would have likely faced broader discovery in a class-action suit weighed by a jury.

Instead, the only surviving claim in this case concerns Meta’s controversial torrenting of books to train Llama, which authors have so far successfully alleged may have violated copyright laws by distributing their works as part of the torrenting process.

Training AI is not akin to teaching “schoolchildren”

According to Chhabria, if rights holders provide evidence of market dilution, that may raise the strongest opposition most likely to win AI copyright fights. So, while Meta technically won this fight against these book authors, the ruling isn’t necessarily a slam dunk for Meta, nor does it offer ample security for any AI company.

Rather than suggest that AI companies can defeat copyright claims on the virtue that their products are “transformative” uses of authors’ works, Chhabria said that cases will win or lose based on allegations of market harm.

He claimed that the “upshot” of his ruling is that he did not create any bright-line rules carving out exceptions for AI companies. Instead, he believes that his ruling makes it clear “that in many circumstances it will be illegal to copy copyright-protected works to train generative AI models without permission. Which means that the companies, to avoid liability for copyright infringement, will generally need to pay copyright holders for the right to use their materials.”

In his order, Chhabria called out Judge William Alsup for focusing his ruling this week in the Anthropic case “heavily on the transformative nature of generative AI while brushing aside concerns about the harm it can inflict on the market for the works it gets trained on.”

Chhabria particularly did not approve that Alsup compared authors’ complaints of the possible market harms that could result if Anthropic’s Claude flooded book markets to the outlandish idea that teaching “schoolchildren to write well” would “result in an explosion of competing works.”

“According to Judge Alsup, this ‘is not the kind of competitive or creative displacement that concerns the Copyright Act,'” Chhabria wrote. “But when it comes to market effects, using books to teach children to write is not remotely like using books to create a product that a single individual could employ to generate countless competing works with a miniscule [sic] fraction of the time and creativity it would otherwise take.

“This inapt analogy is not a basis for blowing off the most important factor in the fair use analysis,” Chhabria cautioned.

Additionally, Meta’s claim that granting authors a win would stop AI innovation “in its tracks” is “ridiculous,” Chhabria wrote, noting that if rights holders win in any of the lawsuits against AI companies today, the only outcome would be that AI companies would have to pay authors—or else rely on materials in the public domain and prove that it’s not necessary to use copyrighted works for AI training after all.

“These products are expected to generate billions, even trillions, of dollars for the companies that are developing them,” Chhabria wrote. “If using copyrighted works to train the models is as necessary as the companies say, they will figure out a way to compensate copyright holders for it.”

Three ways authors can keep fighting AI training

This week’s rulings suggest that the question of whether AI training is transformative has been largely settled.

But as authors continue suing AI companies, with the latest lawsuit lobbed at Microsoft this week, Chhabria suggested that “generally the plaintiff’s only chance to defeat fair use will be to win decisively on” the fourth factor of a fair use analysis, where judges and juries weigh “the effect of the use upon the potential market for or value of the copyrighted work.”

Chhabria suggested that authors had at least three paths to fight AI training on the basis of market harms. First, they could claim that AI outputs “regurgitate their works.” Second, they could “point to the market for licensing their works for AI training and contend that unauthorized copying for training harms that market (or precludes the development of that market).” And third, they could argue that AI outputs could “indirectly substitute” their works by generating “substantially similar” works.

Because the first two arguments failed in the Meta case, Chhabria thinks “the third argument is far more promising” for authors intending to pick up the torch where the 13 authors in the current case have failed.

An interesting wrinkle that may have stopped authors from invoking market dilution as a threat in the Meta case is that Chhabria noted that Meta had argued that “market dilution does not count under the fourth factor.”

But Chhabria clarified “that can’t be right.”

“Indirect substitution is still substitution,” Chhabria wrote. “If someone bought a romance novel written by [a large language model (LLM)] instead of a romance novel written by a human author, the LLM-generated novel is substituting for the human-written one.” Seemingly, the same would go for AI-generated non-fiction books, he suggested.

So while “it’s true that, in many copyright cases, this concept of market dilution or indirect substitution is not particularly important,” AI cases may change the copyright landscape because it “involves a technology that can generate literally millions of secondary works, with a miniscule [sic] fraction of the time and creativity used to create the original works it was trained on,” Chhabria wrote.

This is unprecedented, Chhabria suggested, as no other use “has anything near the potential to flood the market with competing works the way that LLM training does. And so the concept of market dilution becomes highly relevant… Courts can’t stick their heads in the sand to an obvious way that a new technology might severely harm the incentive to create, just because the issue has not come up before.”

In a way, Chhabria’s ruling provides a roadmap for rights holders looking to advance lawsuits against AI companies in the midst of precedent-setting rulings.

Unfortunately for book authors suing Meta who found a sympathetic judge in Chhabria—but only made a “fleeting reference” to indirect substitution in a single report in its filings ahead of yesterday’s ruling—”courts can’t decide cases based on what they think will or should happen in other cases.”

If their allegations were just a little stronger, Chhabria suggested they could have even won on summary judgment, instead of Meta.

“Indeed, it seems likely that market dilution will often cause plaintiffs to decisively win the fourth factor—and thus win the fair use question overall—in cases like this,” Chhabria wrote.

Search

RECENT PRESS RELEASES

Related Post