Bottlenecks to renewable energy integration in South Korea

June 4, 2025

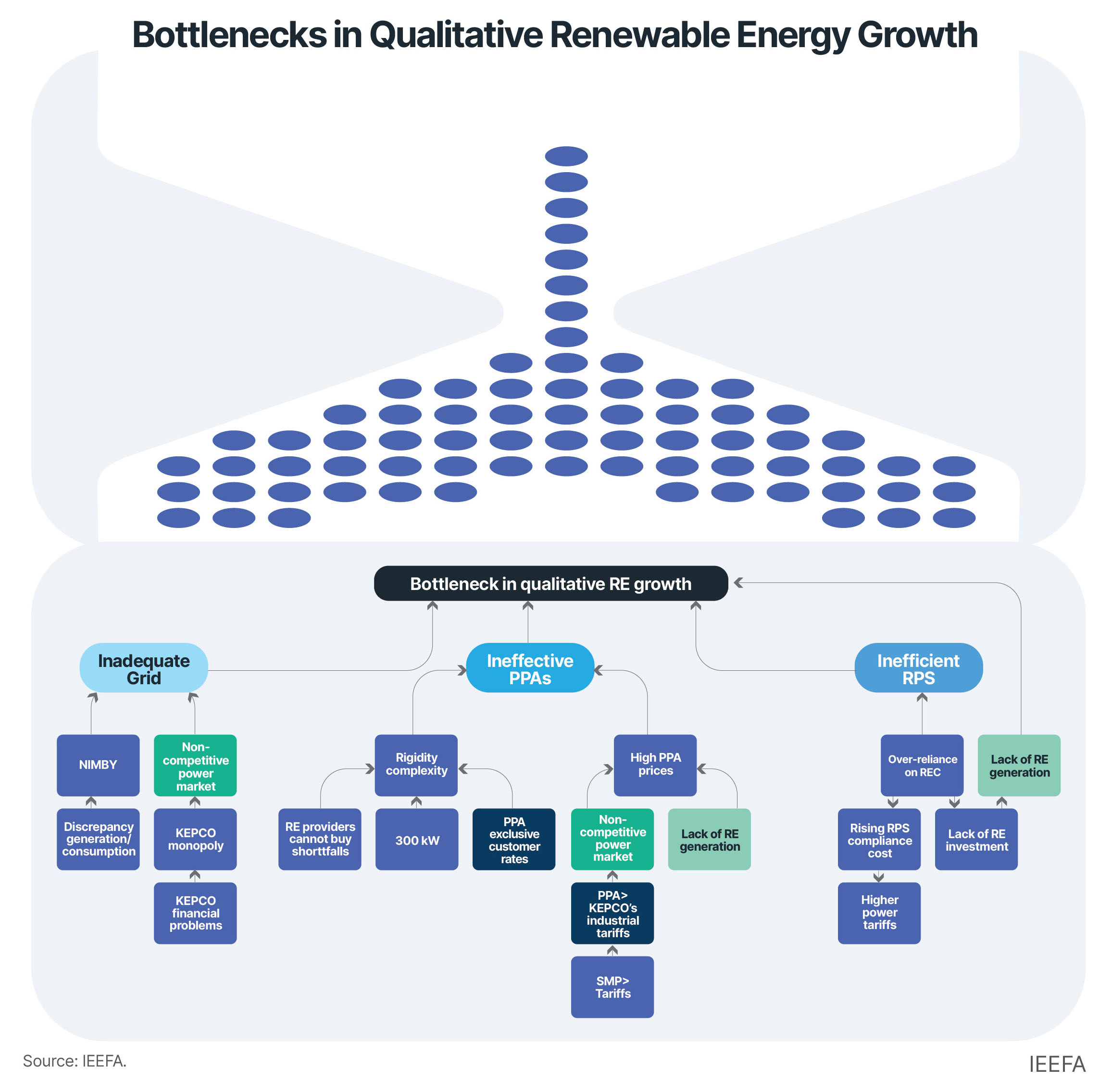

Several bottlenecks have hampered the integration of renewable energy in South Korea’s national grid system. Despite the significant increase in the country’s renewable energy capacity, inadequate transmission and distribution systems, ineffective Power Purchase Agreements (PPAs), and an inefficient Renewable Portfolio Standard (RPS) are obstacles to renewable energy generation.

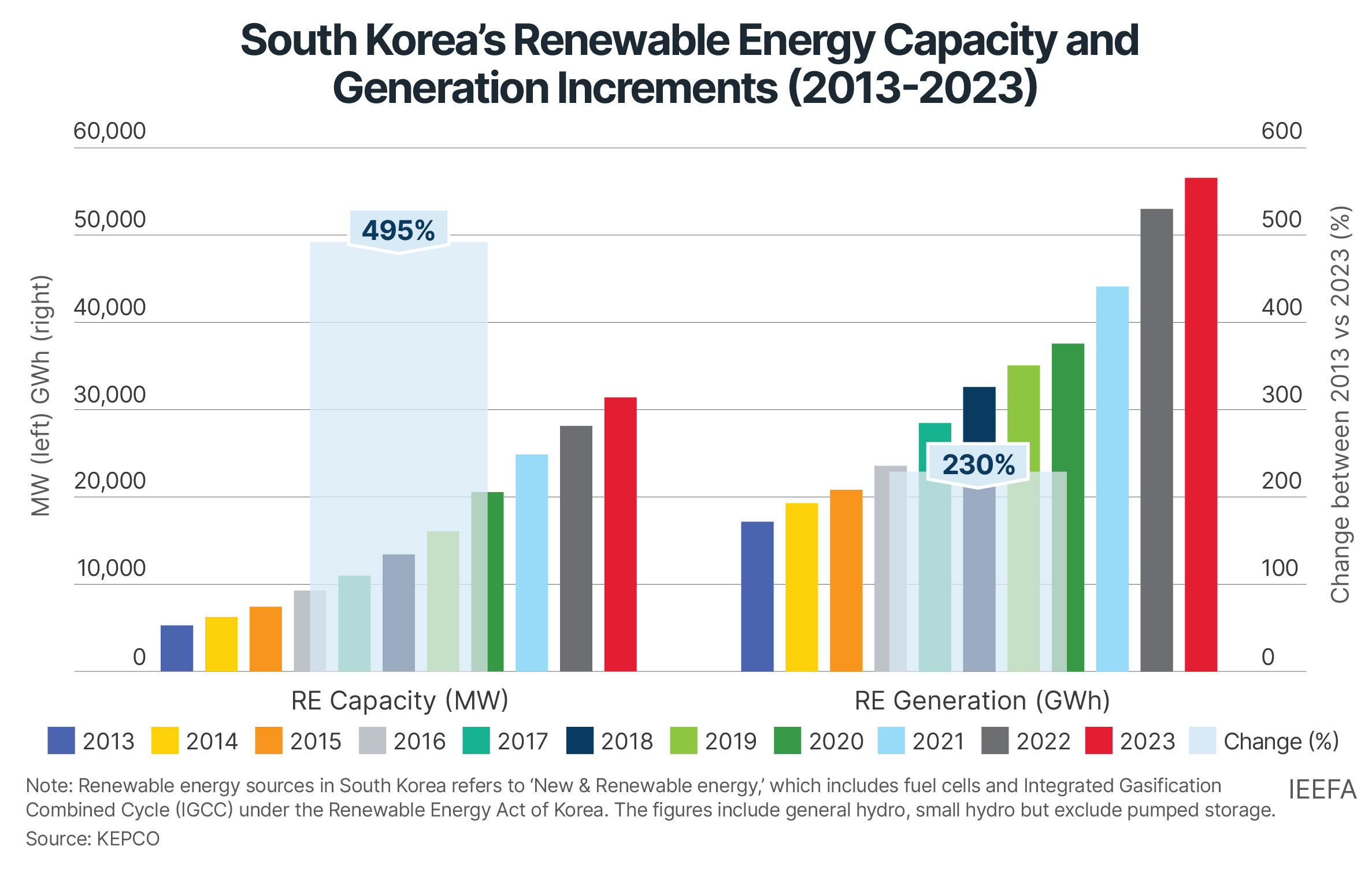

According to data from the Korea Electric Power Corporation (KEPCO), renewable energy capacity increased sixfold from 2013 to 2023, while renewable electricity generation rose only threefold during the same period (Figure 1).

Figure 1: South Korea’s Renewable Energy Capacity and Generation Increments (2013-2023)

As a result, South Korea’s renewable energy transition is lagging behind other countries by at least 15 years. The renewable energy share in the power mix reached 10% for the first time in 2024. However, according to the 11th Basic Plan for Long Term Electricity Supply and Demand (BPLE), South Korea will achieve its 32.95% target only around 2038. This is far short of the 2023 levels for the world (30.25%), the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (33.49%), and Asia (26.73%).

One of the primary bottlenecks delaying renewable energy integration is inadequate grid expansion and modernization. Enhanced transmission infrastructure is needed since renewable energy is often generated far from where power is consumed.

One of the most significant barriers is the challenge of transmission siting, often caused by opposition from local residents, which can delay major grid construction projects by as much as 11 years. Additionally, KEPCO’s monopoly over transmission and distribution has obstructed the efficient implementation of grid expansion and modernization projects. These issues are compounded by a lack of resources due to the utility’s persistent financial problems, further emphasizing the lack of competitiveness in South Korea’s power market structure.

Electricity demand is expected to rise with the development of large-scale semiconductor clusters in Yongin and Artificial Intelligence (AI) data centers in Seoul and Gyeonggi provinces. However, delays in power grid construction and modernization raise concerns about an unstable power supply and a potential weakening of industrial competitiveness.

PPAs have been widely adopted in other countries for sustainability and decarbonization. They offer stable and predictable power purchase prices for consumers and guaranteed long-term revenues and investment incentives for producers.

However, South Korea’s PPA system has failed to establish a ‘virtuous cycle’ that ensures a stable revenue stream for renewable energy suppliers. Such a mechanism would support the expansion of renewable energy generation, increase supply, and lower prices – thereby amplifying demand for PPAs.

The first challenge to the virtuous cycle of PPAs is the restrictive and complex rules and regulations caused by a bifurcated system, including direct PPAs and third-party PPAs. In direct PPAs, the renewable electricity provider acts as an intermediary between the renewable energy generator and the consumer, whereas in third-party PPAs, KEPCO acts as an intermediary. However, renewable energy providers acting as intermediaries for direct PPAs cannot procure additional electricity to cover any shortfalls.

This contrasts with practices in other countries, such as the United States (U.S.), Australia, and many northern European countries, where most PPA participants, including renewable energy generators, renewable energy providers, and consumers, are allowed to freely procure any shortfall from the market.

The second obstacle is the high price of delivered energy. Higher PPA prices disincentivize customers from choosing PPAs over KEPCO’s lower industrial tariffs. Alternatively, they prefer indirect methods, such as purchasing renewable energy certificates (RECs), which do not facilitate the increase of renewable generation. Renewable energy PPA prices are generally lower than wholesale electricity prices in mature markets such as the U.S., Europe, and Australia. This pricing

is supported by declining renewable energy technology costs, government incentives, long-term fixed-price purchase agreements, and the option for direct supply agreements between renewable energy generators and consumers.

PPA prices in South Korea are generally higher than market prices due to a distorted power market structure, limited renewable energy supply, and delayed grid parity — all of which stem from fundamental issues.

South Korea’s RPS has also faced criticism for failing to promote renewable power generation directly. The overreliance on purchasing RECs to fulfill RPS obligations could sharply increase the financial costs associated with compliance. This could lead to suppressed investments and limited direct renewable power generation, especially for public entities.

The current RPS is incompatible with PPA regulations connecting consumers and renewable power generators. RPS fails to promote direct renewable power generation, and this ineffective system has also failed to address grid expansion and modernization inadequacies.

Figure 2: Bottlenecks in Qualitative Renewable Energy Growth

South Korea is implementing several reforms to address the three main challenges in renewable energy integration. However, as policies are interconnected, a more coherent and holistic approach is needed to accelerate the sector’s qualitative growth.

Amid increasing global pressure for decarbonization, South Korea needs to focus not only on expanding capacity but also on the qualitative growth of its renewable energy sector. This shift would also be pivotal for global competitiveness in emerging industrial sectors such as AI and semiconductors.

This executive summary includes references that are available in the full report.

Search

RECENT PRESS RELEASES

Related Post