California Cuts Tax for Legal Weed, Youth Groups Cry Foul

September 22, 2025

The manufacturing floor at Santa Rosa’s CannaCraft is a scene out of Willy Wonka’s weed factory.

Gloved, bonneted workers sort pills in the gel cap room, shiny silver cans twirl down a conveyor belt in the beverage canning room. A merry-go-round-shaped industrial machine grunts and gasps in the infusion room as it sorts watermelon pot gummies into three-ounce portions, then sends them up a roller coaster ramp to be dumped and sealed into electric green and pink packages.

The investment in automation equipment originally designed for packaging M&Ms or potato chips has helped the company stay afloat in California’s legal cannabis market, where the cost of labor, regulation compliance, and taxes levied at almost every stop in the supply chain adds a threefold price differential to legal pot products compared to illegal ones.

“If we weren’t able to do that, our razor-thin margins would not be tenable,” said Tiffany Devitt, CannaCraft’s director of regulatory affairs.

Arguing their industry is overtaxed and overregulated, nearly a hundred legal cannabis companies and their allies convinced the California legislature to give them a break, lowering the state excise tax from 19% to 15%. Gov. Gavin Newsom approved the cut, which will take effect Oct. 1 of this year. But on the other side of the aisle, more than a hundred youth and environmental groups funded by cannabis tax revenues said kids are being betrayed.

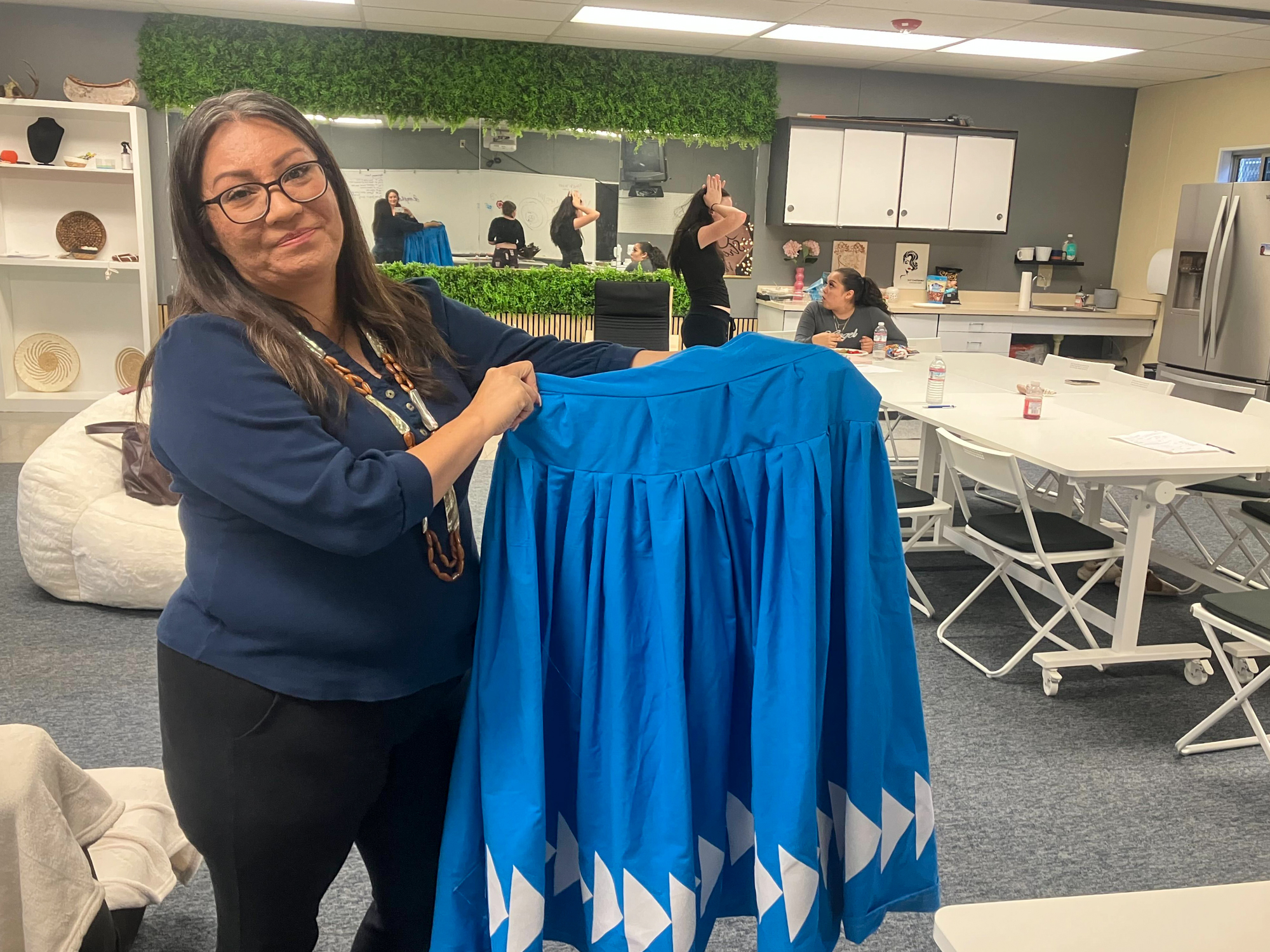

“It’s taking directly from our youth,” said Leticia Aguilar, founder of Native Sisters Circle, a substance use prevention nonprofit for Indigenous girls that gets 80% of its funding from the pot tax.

California voters struck a deal when they voted to legalize recreational cannabis in 2016. Proposition 64 promised to create a marijuana tax fund, with 60% of revenues benefitting youth groups.

But over the years, that financial bargain has come into conflict with another promise in that proposition: one that allows cities and counties across the state to apply whatever local cannabis taxes they wish on top of the state taxes.

For a company like CannaCraft, this means they pay the cost of Sonoma County’s local cannabis cultivation tax — 36 cents per square foot of outdoor crop, and $3 per foot indoors — when they buy cannabis from local farmers.

Then they pay a 1% manufacturing tax to the city of Santa Rosa, a 2% distribution tax to San Diego County, where most of their dispensaries are, and another 10% retail tax to the city of San Diego when they sell them. All of these taxes are compounded, meaning they get baked into the price at each stage before the 19% state excise tax is added on top.

“At the end of the day, you end up with a total tax burden of around 40%,” Devitt said.

This breaks the first and most fundamental promise made to voters, she argued, to establish and protect a legal, regulated market.

“Consumers are price sensitive. You raise the prices, they go to the illicit market, and it’s hard to get them back,” Devitt said. “They find their hook up and they’re like, ‘Ah, this works for me, it’s a lot cheaper. Buy it from Uncle Joe.’”

Only 40% of cannabis consumed in California comes from licensed dealers, according to the state Department of Cannabis Control. Lawmakers, including the governor, argued lowering the state tax would help stem closures and bankruptcies of legal businesses and help them regain enough of a foothold to compete with the illicit market.

“If we continue to pile on more taxes and fees onto our struggling small cannabis businesses, California’s cannabis culture is under serious threat of extinction,” said state Assemblymember Matt Haney, D-San Francisco, in a statement. “Instead, we should be looking at how we can support this industry.”

At the same time, the legal market has continued to grow every year, with the total volume of retail sales for nearly all products going up, according to a report prepared for the state by a consultancy firm ERA Economics. Groups that oppose the tax cut argue business turmoil should be expected for the new industry.

“It’s sort of like the restaurant industry, where restaurants open, restaurants close. There’s a settling out going on,” said Jim Keddy, executive director of Youth Forward. “We’re trying to take the long view here.”

Reducing the cannabis excise tax will strip the marijuana tax fund of $180 million per year, according to the California Department of Tax and Fee Administration, and Keddy said groups that focus on substance use prevention will be among those hit the hardest by the funding loss.

“I’m not a reefer madness person,” Keddy said. “I do think as a society, we do better to have a legal industry, but I also believe in an industry that has to give something back.”

Youth prevention has come a long way since the Reagan-era “Just Say No” campaigns of the 1980s. Research shows that what keeps kids away from drugs is a strong sense of community and purpose.

For the last seven years, Angelina Hinojosa, 20, has spent her Tuesday afternoons with the Native Sisters Circle. The group of Native teens and young women meets in a modular classroom behind a former elementary school shuttered by previous government funding cuts.

Shelves are lined with beads, abalone, and feathers for making jewelry; two sewing machines, where many girls learn to sew for the first time, sit at the ready in the back of the room; and the refrigerator and cabinets are fully stocked with sandwiches, snacks, and popsicles.

Hinojosa and other girls said it is the only place in their lives where making friends and fitting in has nothing to do with weed.

“At my high school, everybody smoked, even people that played sports smoked,” said Hinojosa, now a college student at Sacramento State. “If you’re already in a marginalized group, it’s so easy for you to get sucked into that crowd. It’s so easy.”

But learning how to sew traditional skirts, to weave baskets and make jewelry, gave her a new sense of identity and belonging outside of drug circles.

“Nothing helped me. Therapy didn’t help me. Counseling didn’t help me,” Hinojosa said. “For me, when I basket-weave, everything goes away. I feel like that’s prevention. Culture is prevention.”

Native Sisters Circle was founded with Proposition 64 money. It formed its own nonprofit with Proposition 64 money. The next three-year grant that the organization will apply for comes from Proposition 64 money. Aguilar said cutting that funding violates the agreement California made to reinvest in tribal communities harmed by illegal cannabis production. “It just further damages our community,” she said.

But it may not be that simple. Though it may seem counterintuitive, higher tax rates do not always result in higher tax revenues, said Robin Goldstein, an economist at UC Davis and co-author of the book Can Legal Weed Win? The Blunt Realities of Cannabis Economics.

“If you raise the tax enough, then you just have so little product in the legal market that you could even collect less tax,” he said. “Every additional percent you raise the taxes is just another giveaway to the illegal market.”

There is a sweet spot in this economic theory: an optimal tax rate that incentivizes buyers and sellers to stay in the legal market and drives tax revenues to their peak. The thing is, no one knows exactly what that magic number is, and it varies depending on the economic context and other policies at play.

“It’s a judgment call,” Goldstein said.

California lawmakers have placed their bets on 15%, in the hope that cutting the state cannabis tax will actually yield more money for youth groups in the long run.

Search

RECENT PRESS RELEASES

Related Post