California is Lagging on Wind Development. Why?

January 29, 2026

California has made tremendous progress on transitioning to clean electricity. The state keeps breaking records for the amount of clean energy powering California. And after a long pause, emissions from California’s electricity sector are finally going down again.

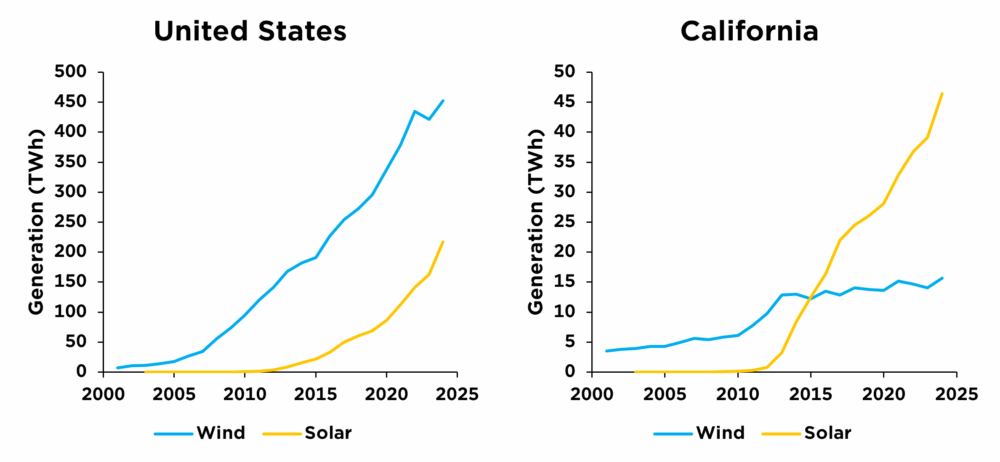

It won’t surprise anyone that solar has been the star of the show, responsible for nearly all of California’s clean energy progress over the past decade. And California’s early investments in solar have helped transform the industry to the point where solar is now one of the least expensive sources of electricity. It’s a remarkable success story.

But there’s an old saying about not putting all your eggs in one basket.

As California’s solar industry flourished, California’s wind industry has languished. Despite the fact that wind is now the number one source of renewable electricity in the United States, California has barely added any wind to its grid over the past decade.

So what happened? Why has California added so little wind to its grid? Is more on the way? And how much more wind does California need in the first place?

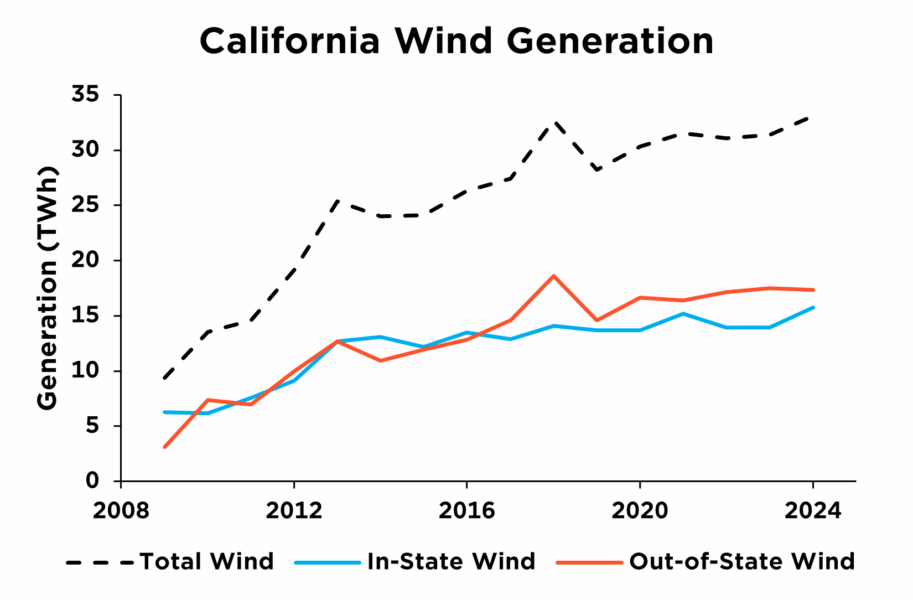

California has a long history with wind power. It was home to one of the first large-scale wind farms, which was built in Altamont Pass in the early 1980s. More recently, the last big buildout of wind power occurred in the early 2010s, with many of those projects built in Tehachapi Pass. Without any big investments since then, California has had roughly six gigawatts (GW) of in-state wind capacity since 2013.

Compared to the rest of the country, something very strange has happened in California. As wind generation increased dramatically nationwide over the past decade, wind generation has only inched up in California. The state’s wind industry has come to a standstill.

But that’s not the whole story. California also imports a big chunk of wind energy from neighboring states. Imports of out-of-state wind have grown slightly more than in-state wind generation over the past decade, but not by much. The net effect is that the total amount of wind generation serving California electricity demand has grown very modestly, by 31%, since 2013. In comparison, solar generation grew by 1000% over that same period. No, that’s not a typo. Wind has just been doing very poorly in comparison to solar.

There are a variety of factors that likely led to the slowdown of wind development in California.

For starters, solar got cheap. Renewable energy procurement in California has largely been driven by renewable portfolio standard requirements, which don’t distinguish between solar and wind. So when solar prices dropped sharply, California electricity providers went all-in on solar and procured much less wind.

Another factor is that there are only a handful of good locations for wind power in California, and many of the best spots have already been built out. The best locations for wind also tend to be more remote and therefore require longer transmission lines to connect to the grid, which only increases project cost and complexity. Not to mention the fact that wind projects tend to face more permitting obstacles in the form of local opposition, with eight counties in California enacting significant barriers to wind development.

It’s gotten so tough to develop wind in California that very few developers are even trying to do it anymore. Instead, developers are focusing on solar and storage projects. So even though I’ve heard California electricity providers talk about how they would love to buy more wind power, there just isn’t much to buy.

At this point, it’s reasonable to ask if California even needs more wind. Perhaps the state could just reach its clean energy goals by continuing to go big on solar and storage. And if that were the case, there wouldn’t be much to worry about.

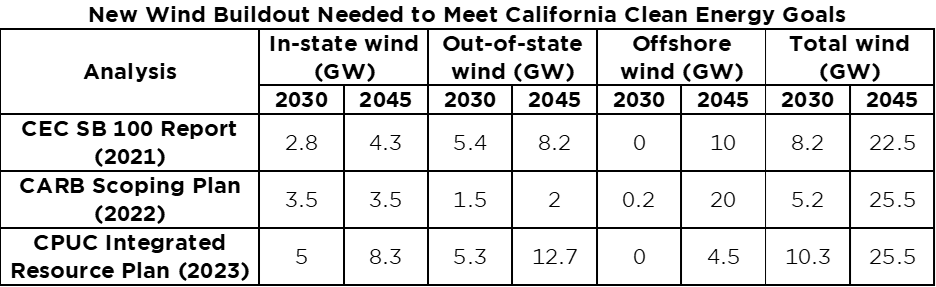

However, all signs point towards a substantial need for more wind power. Various state agencies have conducted analyses to assess the buildout of clean energy resources that will be required for the state to reach its clean energy goals. While the exact mix of in-state, out-of-state, and offshore wind varies significantly between studies, the overall amount of new wind that California needs is relatively consistent. The studies indicate that the state will need 5.2-10.3 GW of new wind by 2030 and 22.5-25.5 GW of new wind by 2045. As a reminder, California currently has a little more than 6 GW of in-state wind, a number that’s hardly budged since 2013. So California would need to kick start wind development for there to be any hope of achieving those buildouts.

All three studies in the table above point towards a big need for more wind power because, as I mentioned earlier, it’s best not to put all your eggs in one basket. The studies all have three key ingredients for decarbonizing California’s grid: solar, wind, and storage. When you take away one of those key ingredients, it’s much harder to achieve the same results. For example, when the California Public Utilities Commission (CPUC) studied what it would take to meet clean energy goals with very little additional wind power available, it found that California would need a lot more solar and storage in addition to much more of a new key ingredient: geothermal.

This illustrates the point that “resource diversity” is one of the keys to achieving clean energy goals. It helps tremendously to have many different technologies (solar, wind, geothermal, hydropower, short-duration storage, long-duration storage, etc.) in many different places (in-state, out-of-state, offshore) to facilitate an affordable and reliable transition to clean electricity. Taking away one of the key technological options only makes it more difficult to maintain grid reliability and more expensive to transition.

There are three different categories of wind power that California is planning to build: in-state, out-of-state, and offshore. In short, the outlook for in-state wind is not good, the outlook for out-of-state wind is not bad, and the outlook for offshore wind is murky at best.

California’s grid operator, CAISO, manages most of the grid in California. Therefore, most of California’s in-state wind projects go through the CAISO interconnection queue to connect to the grid. Because the interconnection process is backed up and takes so long (though it’s getting better!), a wind project would need to be fairly far along in the process in order to come online anytime soon. So the projects in the queue are what we have to work with for now.

When you look for wind projects in the CAISO’s interconnection queue, there’s nearly 7.7 GW in total, which seems promising! But the more you dig into the details, the more you realize only a small fraction of those projects appear to be viable.

- First, some of those wind projects have already been built, but they’re still lingering in the queue because other components of the project are incomplete. For example, the 265 megawatt (MW, or 0.265 GW) Ocotillo Wind project came online in 2013, but there’s an energy storage component to the project that is seemingly incomplete.

- Second, some projects are multi-technology projects that include wind, but the developers seem to have changed their plans and focused on other technologies. For example, the Potentia-Viridi project was ostensibly going to have 400 MW each of wind, solar, and storage; however, a recent permit application for the project only included energy storage.

- Third, some projects have been stalled for years and have little, if any, hope of getting built. For example, after being denied permits by local officials, the 200 MW Fountain Wind project entered the California Energy Commission’s (CEC) “opt-in certification program” to bypass the local approval process. However, the Commission also rejected the project late last year due in large part to intense local and tribal opposition.

- Finally, some projects are just long shots (or in some cases, may have been speculative all along). For example, Windwalker Offshore would be a 1 GW floating offshore wind project on the central coast of California. But with a federal administration hostile to offshore wind, it’s difficult to imagine this project coming online anytime soon. (More on offshore wind later.)

It’s hard to say with certainty how many projects in the queue are truly viable, but after reviewing the data and asking folks in the industry, I’d say there’s maybe 2 GW that could come online in the next decade. And a handful of projects are clearly happening. For example, the 150 MW Gonzaga Ridge Wind Project is scheduled to come online in 2026, and the 100 MW Keyhole Wind Project is scheduled to come online in 2028.

But collectively, these projects aren’t anywhere close to the amount of wind California has been planning to build.

Out-of-state wind is the only bright spot in the outlook for California wind power. There are three transmission lines that are quite far along in the development process, and those could bring substantial amounts of wind power into California.

- The SunZia Project includes a 3 GW transmission line that will connect to a 3.5 GW wind project in New Mexico. California will receive most of the output from the wind project, at least 2.1 GW, and is scheduled to start delivering energy this year. So California will receive a big bump in wind power very soon!

- Transwest Express is also a 3 GW transmission line that will connect to a 3.5 GW wind project in Wyoming. California will have access to at least 1.5 GW of wind on the transmission line. Both the wind project and transmission line are currently under construction, and they should both be operational by 2030.

- SWIP-North is a 2 GW transmission line that will bring Idaho wind power to California, though California will only get 1.1 GW of that capacity. Construction is to begin this year, and the line is scheduled to be operational by 2028. However, the federal government threw a wrench in the mix with its cancellation of the 1 GW Lava Ridge Wind Project, an Idaho wind project that could have sent power over the line to California. While development of the transmission line is still going ahead, the energy resources being built at the end are still in flux.

Collectively, these transmission lines could bring many gigawatts of wind power to California. Assuming all goes well with these projects, California is roughly on track to reach its out-of-state wind targets in 2030.

But longer term, California will need even more out-of-state wind, and beyond these three lines, I’m unaware of any other projects in the works. That’s a problem because these transmission lines have taken decades to build, with the process beginning in the mid-2000s (if not earlier). Since multi-state transmission projects take so long, that means it may be quite a while before California has more opportunities to increase its supply of out-of-state wind.

If you’ve been following the news, you may be aware that the current federal administration is not particularly fond of offshore wind. But despite construction pauses and funding cancellations, California is still going ahead with its big plans for offshore wind.

In 2024, shortly after the CEC established a goal to build 25 GW of offshore wind by 2045, the CPUC ordered the procurement of up to 7.6 GW of offshore wind to come online by 2037. The state will start trying to procure those resources next year, which would represent the first big tranche of offshore wind development. In the meantime, the state has set aside hundreds of millions of dollars for offshore wind port development, which is now starting to be spent.

But building up the offshore wind industry isn’t going to be easy. To build offshore wind in federal waters, developers may decide to wait for a federal administration that isn’t so hostile to the industry. I think that, at best, California offshore wind will be delayed.

California is going to need resource diversity to achieve its clean energy goals. Solar and storage will get the state a long way toward its goals, but it will need other clean energy technologies as well. Technically, California could reach its goals without much more wind if another clean energy technology came along that was cost-effective and scalable, for example, next-generation geothermal. But barring any dramatic technological advances, California is going to need a lot more wind.

I think it’s clear that California’s goal of adding 5.2-10.3 GW of new wind by 2030 and 22.5-25.5 GW of new wind by 2045 will be difficult to attain at the rate things are going. The first step will be to get early development activity going again both for in-state and out-of-state wind projects beyond the current pipeline. To do that, the state may need to identify and reduce barriers to in-state wind development and initiate the process to build more transmission lines that enable both in-state and out-of-state wind projects. At the very least, the state should study what it will take to meet clean energy goals without so much wind power to assess the alternatives, which is already in the works.

There likely isn’t going to be one single solution, but the first step is to acknowledge the problem: California is falling behind on wind development. The second step: let’s fix it!

Search

RECENT PRESS RELEASES

Related Post