Cancer risk in Louisiana’s industrial parishes is underestimated by EPA, study says

October 8, 2025

Cancer risks in parts of Louisiana’s industrial area between New Orleans and Baton Rouge are up to 11 times higher than estimates by the Environmental Protection Agency, according to a study by scientists at Johns Hopkins University.

In a peer-reviewed study that aimed to measure the prevalence of 17 pollutants and compare that to measurements used in EPA models, researchers deployed a mobile air monitoring lab across Ascension, Iberville, St. James and St. John the Baptist parishes. They then used the concentrations of those chemicals in the air to estimate cancer risks in 15 different census tracts.

In all but one of those tracts, cancer risks from air pollutants outweighed the estimates from the EPA’s models. All of the census tracts had “unacceptable” levels of cancer risk, the researchers found.

The Johns Hopkins researchers attribute the differences in the two models to differences in how the pollutants were measured. They used real-time data on air pollutants over a month-long period in February 2023. The EPA model is based in part on emissions data from state agencies and industrial facilities.

Much of this data is self-reported from industry, said Peter Decarlo, a professor of environmental health and engineering at Johns Hopkins who led the research.

“I think what our results really highlight is that we can’t rely on self-reported emissions data from facilities to estimate the health risks from air pollutants,” he said.

The study itself said that there is an “urgent need for comprehensive measurements of key carcinogenic air pollutants, especially in areas with a history of disproportionate environmental health burdens.”

David Cresson, the president of the Louisiana Chemical Association and Louisiana Chemical Industry Alliance, which advocates for the industry, questioned whether the measurements by researchers, which were conducted during a single month, accurately captures the full picture.

In an email, he argued that the month-long mobile measurements “can capture peaks that are not representative of year-round community exposure” and said that the pollutants can have multiple sources in addition to area plants, and so “it is not scientifically sound to assign total risk to any single sector.”

Comparing the study’s measurements to self-reported industry figures, he said, overlooks other tools “that underpin federal and state emissions reporting.”

Joe Robledo, a press officer for the EPA region that includes Louisiana, said the EPA cannot comment on studies performed outside the agency.

‘A wake-up call’

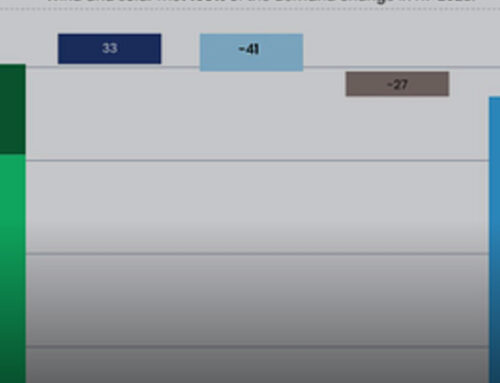

Census tracts in Iberville and Ascension parishes had some of the highest cancer risk levels, according to the researchers’ findings. The tract with the highest rates is an Iberville Parish tract with a cancer risk of 560 per 1 million people. The EPA estimate for this area, by contrast, was around 50 per 1 million.

The subsequent three tracts in Ascension Parish similarly had cancer risks around 500 or higher per 1 million, based on the researchers’ findings, and EPA estimates under 100 per 1 million.

The EPA states on its website that “air toxics have no universal, predefined risk levels that clearly represent acceptable or unacceptable thresholds” but notes a “general presumption” that sets an upper level of acceptable risk at 100 per 1 million lifetime cancer risk for the most exposed person.

For environmental advocates living in an area they often refer to as Cancer Alley due to health risks attributed to industry pollution, the study’s findings add a new level of concern.

“I thought it was extreme before, but this is even beyond what I imagined,” said Jo Banner, who co-leads the St. John the Baptist community group The Descendants Project. “I say it’s a wake-up call, but I know many people won’t register it.”

While the EPA model accumulates data from across the country, Decarlo said states have the ability to gather more data and better assess cancer risks. The EPA website notes that the federal screening tool, called the AirToxScreen, can spur state and local agencies, “inform monitoring programs” and “focus community efforts.”

The Louisiana Department of Environmental Quality declined to comment on the study.

Political backdrop

The research, released in a peer-reviewed journal of the National Academy of Sciences, arrives as advocacy organizations are embroiled in a legal fight over a state air monitoring law that limits groups’ ability to allege environmental violations.

The law requires community groups to use the latest federal air monitoring equipment in order to allege violations of the Clean Air Act or other laws. The air monitoring tools the researchers used in their new study do not fit those federal requirements.

Supporters of the rule in the state’s chemical industry say it standardizes air monitoring standards, but advocates say the rule “effectively bans” community groups from their sharing air pollution findings or advocating for redress.

Decarlo, whose work on air pollution has influenced community organizers in Louisiana, said that the scientific tools the Johns Hopkins team employed are better than the monitors required by federal regulators.

“We’ve got the Ferraris and Lamborghinis to do the measurements and they’re using police cruisers,” he said.

On the federal level, President Donald Trump recently exempted a dozen Louisiana industrial facilities from following a Biden-era rule aimed at lowering pollution and cancer risk in mostly poor, minority areas.

Trump’s July proclamation cites technological limits, cost concerns and national security to put off compliance until 2028 for major petrochemical companies in the Baton Rouge to New Orleans industrial corridor and Lake Charles area.

The EPA rule was expected to reduce cancer risk by 96 percent for those living within six miles of pollution facilities, according to the Federal Register.

Search

RECENT PRESS RELEASES

Related Post