Chaos of 2020 Can’t Match 2008 But the Gut Punch Feels Familiar

March 11, 2020

- Difference of opinion on how long and how deep this one goes

- ‘Lowest since 2008,’ ‘highest since 2008’ are common refrains

With world markets ablaze, it’s tempting to compare these dizzying days to the last time so many asset values fell through a trap door. Though there are similarities, 2008 was different in many ways.

That’s not to say today’s pain doesn’t cut deep. The litany of losses — biggest oil-price plunge since 1991, record-low Treasury yields, the S&P 500 down 12% in 12 trading days — may not match the darkest days after Lehman Brothers Holdings Inc.’s bankruptcy filing, when Wall Streeters tapped their ATMs because they thought banks had little cash left and solvency worries dogged even the biggest institutions. But the panic that comes with the uncontrollable loss of years of meticulously amassed wealth has activated a kind of muscle memory for people who were around last time.

“The situation is much different than 2008, but from the standpoint of emotional fear it is very similar,” said Jim Paulsen, chief investment strategist at Leuthold Group.

Stocks were faring better on Tuesday, and oil prices gained back some of their losses. But for this market chaos to be credibly compared with 2008 is a feat. The financial crisis remains a tough act for other downturns to follow. Millions of Americans lost their homes after lenders sold them loans they couldn’t afford. When banks packaged the loans into securities and peddled them to international investors, who lost their shirts, the contagion associated with so-called subprime borrowers sparked the longest and deepest recession in the U.S. since the 1930s.

But 2008 didn’t have the 2020 version of contagion — the deadly coronavirus, which seems to pop up in new places every few hours.

Those who remember with dread when financial policy makers, including Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke, erroneously said that the subprime contagion was “contained” are no doubt experiencing a chilling déjà vu these days, as the same word is used by White House advisers including Larry Kudlow and Kellyanne Conway to describe the virus.

“What’s happening now isn’t about a weak financial sector, which was the case in 2008, when there was also a lot of uncertainty about who held troubled securities,” said Nellie Liang, former director of the Fed’s financial stability division and now a Brookings Institution researcher. “This is about a slowing economy and uncertainty about how a virus will play out.”

Oil Prices

It’s also about crashing oil prices triggered by a blinking contest between Saudi Arabia and Russia. Though U.S. banks have loans out to shale drillers, some of whom may not survive, the financial system is stronger today than it was in 2008. Government regulations enacted since the crisis require banks to carry bigger reserves in case of loan losses. An 11-year bull market in stocks and the longest economic expansion in history added to their health.

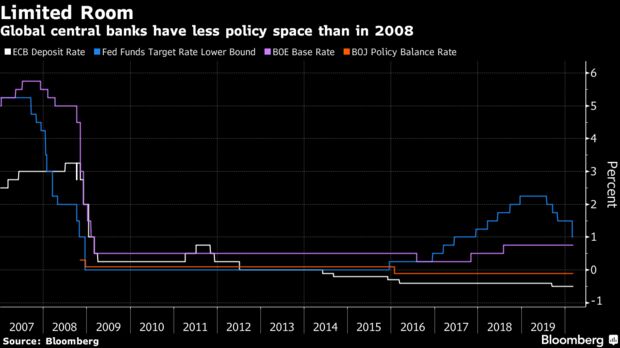

Fewer Bullets

In an echo of 2008, JPMorgan Securities Chief Economist Bruce Kasman warned of “a powerful global deflationary wave.” That’s when central banks usually swoop in to save the day. Starting in 2007, the Fed showered markets with 10 rate cuts, bringing the borrowing benchmark from 5.25% to near zero, where it stayed for seven years.This time, central banks have fewer bullets in their bandoliers. Interest rates around the world are already flirting with zero, and in some cases have dipped well below. Even emergency cuts may not be the answer, as the Fed discovered last week. Cheaper money is unlikely to be the magic wand that provides materials for starving factories or allay coronavirus fears that keep folks from shopping, traveling and dining out.

“The problem we have is that the classic tool of monetary policy is basically not going to be very effective,” Philipp Hildebrand, vice chairman of BlackRock Inc., told Bloomberg TV on Tuesday.

The years of low, low rates in the U.S. have left an oily aftertaste. There was a lot of borrowing. Business investment used to rise when U.S. companies took on more debt because most companies borrowed to add capacity. But since the crisis, many indebted companies used that cheap money to borrow themselves out of insolvency. Many others used it to buy back shares and finance dividend payouts.

Read more: Buyback Frenzy Means Fed Can’t Lift the Economy Like It Used To

That’s left them more at risk in a contraction, said William Lazonick, a professor at the University of Massachusetts at Lowell.

Fragile Companies

“Buybacks, especially to the extent that they have been debt-financed, have increased the fragility of these companies,” Lazonick said. He said he’d been worrying that “something was going to happen that was unexpected that would exploit this vulnerability. And now we’re seeing this with the virus.”

This year’s turmoil may be a kind of mini-2008, but it’s still swollen with

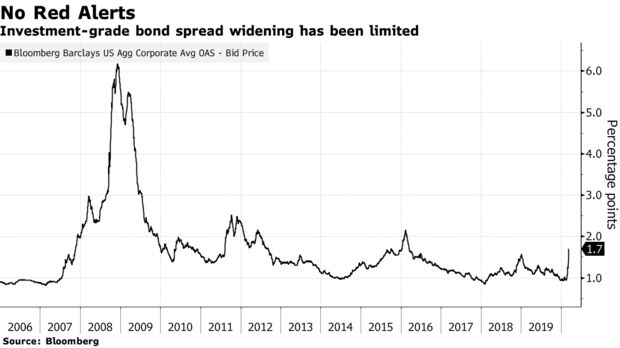

superlatives. A credit-derivatives index that measures the perceived risk of investment-grade corporate credit surged Monday by the most since Lehman. The entire U.S. yield curve fell below 1% for the first time in history. U.K. bond yields tumbled below zero for the first time. Germany’s 5-year government debt yield dropped and now hovers at about minus 1%. That came on a day when U.S. stocks plunged nearly 8%, its biggest one-day drop since — you guessed it — 2008.

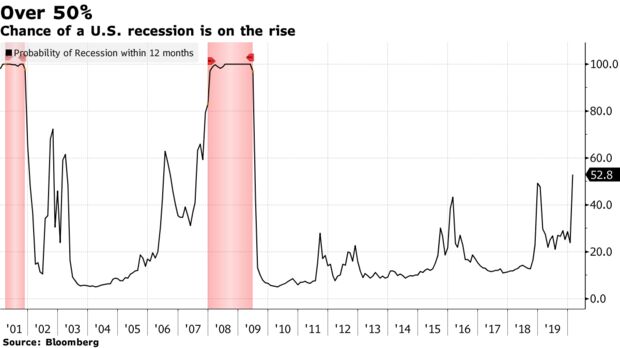

The chance of a U.S. recession in the next 12 months rose to 53%, according to the Bloomberg Economics model. That’s up from 24% in January and the highest since the last U.S. recession, which ended in June 2009 after 18 months.

How Long?

How long will the pain last this time? Many people are still grappling with the fallout from 2008, whether it be curtailed careers, homes never recovering their value or

“Two thousand eight was all about banks, funding and very concentrated risks,” said Alessandro Tentori, chief investment officer at Axa Investment Managers. “This feels more akin to a very strong, but classic recession, albeit with a high leverage which will need time and pain to be worked through.”

On the other hand, according to Isabelle Mateos y Lago, chief multi-asset strategist at BlackRock Investment Institute, unless this “temporary shock is badly mishandled,” it shouldn’t prove long lasting.

Mateos y Lago is joined in her thinking by Torsten Slok, Deutsche Bank AG’s chief economist, who said Monday any recession and slowdown in earnings won’t be as bad as 2008.

Australian Prime Minister Scott Morrison disagreed, at least as far as his country was concerned. He said Monday the hit from the coronavirus would be harder on Australia than the global financial crisis.

“The bottom in the stock market is still to come,” said Jim Bianco, president and founder of Bianco Research and a Bloomberg Opinion contributor. “September 2008 wasn’t the bottom. It was telling us the data was going to get really bad. And what is happening now is the data is about to get really bad.”

— With assistance by Simon Kennedy, and Jason Sc

Search

RECENT PRESS RELEASES

Related Post