Cop30: calls for new urgency to talks as studies show global warming may reach 2.5C

November 17, 2025

South Korea – the world’s fourth-largest importer of thermal coal importer and home to the seventh-largest coal power fleet – has joined a group of about 60 countries pledging to wean itself off the fossil fuel.

Korea and Bahrain have been announced as the latest members of the “powering past coal alliance“, which also counts about 120 sub-national governments, businesses and organisations as members.

Bahrain has no coal-fired generators and its membership just means it promises not to build any. But South Korea buys about 8% of thermal coal sold on the global market and gets about 30% of its electricity from burning it.

The pledge commits it to retiring 62 coal plants over the next 15 years. Forty already have confirmed closure dates.

South Korea’s minister of climate, energy and environment, Kim Sung-hwan, said the pledge demonstrated the country’s commitment to “accelerating a just and clean energy transition”.

“The shift from coal to clean power is not only essential for the climate. It will also help both the Republic of Korea and all other countries increase our energy security, boost the competitiveness of our businesses, and create thousands of jobs,” he said.

The country has faced criticism for dropping a 100% renewable energy target and not acting faster on coal. The Climate Action Tracker found it should phase out coal power by 2030 and gas power shortly after if its action were to be compatible with the goals of the Paris agreement.

South Korea is also a significant importer of metallurgical coal, used in steelmaking. It has substantial nuclear and gas-power fleets, each supplying roughly 30% of its electricity.

Poor and vulnerable countries need reassurance that Cop30 will produce agreement on a just transition, and more support from rich countries for adaptation efforts in the developing world, the Burkina Faso negotiator Princess Abze Djigma has told the Guardian.

“We need predictable finance,” said Abze, a descendent of the legendary warrior princess Yennenga, who lived in the 12th century and is considered the forebear of the Mossi people. “We need grant-based finance, because countries like mine, the least developed countries, we are facing a big debt burden. Some countries are paying more to service debts than to build schools or health services.”

In an investigation of climate finance, the Guardian has found that a large proportion of climate finance is still being provided in the form of loans rather than grants, though it is hard to establish how much countries are paying in interest or repayments.

“It’s taking money out [of poor countries’ budgets] that could go to more schools, more sanitation, more health services, more development,” said Abze. Countries were also still feeling the after-effects of the Covid-19 pandemic, she added. “We still haven’t recovered completely from the slowdown of the economy.”

She also called for Cop30 to set more ambitious goals on adaptation finance for poor countries. “We need to find the kind of climate finance that will help country like Burkina Faso to implement its national adaptation plan. We need to be able to store water, to manage water from heavy floods. The technology exists where you can have artificial underground lakes. But we need money for that.”

Infrastructure to store water, which both avoids flooding and can be used in dry periods, would improve food security, in a virtuous circle. “That would also create jobs for the youth, to stay in the countryside,” she said. “Nobody likes to migrate. You migrate because you’re forced to, because you don’t see hope.”

Abze leads negotiations for Burkina Faso on the just transition, a key issue at Cop30. “I have a mandate, starting from Princess Yennenga. That is the legacy, and I have to respond, to improve the life of the community, and that is that message that we bring into our fellows, to our brothers and sisters.”

There was a brief flurry of noise in the “where on Earth will Cop31 be held” guessing game on the weekend.

For those who have not been paying attention: Australia and Turkey have rival bids to host next year’s Cop. They have for years. Australia’s bid is to co-host a “Pacific Cop” with Pacific island nations.

Under UN rules, the decision must be resolved by consensus. Australia has had the overwhelming support of the countries in the Western Europe and Others Group, from which next year’s host must be selected – but both countries remain in the race.

If the stand-off isn’t resolved, hosting responsibilities fall by default to Germany, which is home to the UN climate headquarters in Bonn. But Germany doesn’t want to host Cop31.

The leaders of the two countries, Anthony Albanese and Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, have recently exchanged correspondence over a potential deal to sort it out, without success.

Reuters reported on Sunday that Turkey had proposed on the sidelines of the UN general assembly in September that the two countries jointly lead the conference. Australia also made proposals, including that Turkey could host other events linked to Cop31. The Guardian reported on these negotiations at the time and since.

The latest news story prompted a journalist to ask Albanese about it at a media conference in Melbourne on Monday. He flatly dismissed the idea of a jointly-led Cop, saying:

“No, we won’t be co-hosting, because co-hosting isn’t provided for under the rules of the UNFCCC [the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change].

So, that’s not an option, and people are aware that that’s not an option, which is why it’s been ruled out.”

So the wait continues.

You can read a more on the deadlock in this piece from Friday.

President Lula da Silva of Brazil has called Cop30 the “Cop of truth”. For negotiators, it may become known as the Cop of roadmaps.

Many countries are hoping to begin the process here of a roadmap to “transition away from fossil fuels”, the key promise made at Cop28 in 2023 but not followed up since then. Marina Silva, Brazil’s environment minister, in an interview with the Guardian, urged all countries to have the courage to address the issue, saying: “The map is an answer to our scientific knowledge [of the climate crisis]. It is an ethical answer.”

The Baku to Belem roadmap on the $1.3 trillion was published in Belem during the leaders’ summit that preceded the formal opening of Cop30, to much approval from governments. It delivered a menu of options, such as levies on frequent flyers and on fossil fuels, or new taxes on financial transactions, that would raise the $1.3 trillion promised to poor countries each year by 2035.

Now it looks like there could be more roadmaps to come. On Sunday night, Cop president Andre Correa do Lago published his promised “note” on the progress of the presidency consultations which have been taking place since last Monday.

The presidency consultations were a neat way of avoiding a damaging and delaying fight over what should be on the Cop agenda. While the less contentious items proposed for the Cop agenda were allowed to proceed – and many have already been resolved or are approaching resolution – the four trickiest issues were set aside to be dealt with separately.

The four issues are: trade; transparency; finance; and addressing the shortfall between the emissions-cutting pledges countries have made, and the cuts needed to limit global heating to 1.5C. (The transition away from fossil fuels, though probably the most controversial issue at this Cop, was not on the list because it is so explosive it can only be dealt with away from the formal agenda.)

In his note, do Lago sets out the possibility of a new roadmap, this time on the 1.5C issue. Ahead of Cop, countries were supposed to submit new national climate plans, called “nationally determined contributions” (NDCs) under the Paris agreement. These set out targets on future emissions, and measures to achieve them. Nearly 120 NDCs have so far been filed, but some key countries are still missing – India, for instance – and the current submissions would result in temperature rises of about 2.5C, way above the 1.5C target.

Technically, under the Paris agreement, countries need not assess and respond to the NDCs for another three years, until the next “global stocktake”– a periodic assessment of progress towards the goal of limiting temperature rises to 1.5C. China and some of its allies want to stick to the letter of the Paris agreement and refuse to discuss the NDCs in Belem.

But many other countries, and most campaigners, believe that – with temperatures already at 1.5C above pre-industrial levels, and rising – would be grossly inadequate. If Cop30 does not set out some credible response to the shortfall, and a pathway to achieving the 1.5C target, it will be counted a failure by many.

One potential compromise listed by do Lago is for a “roadmap”. If this were adopted, it would mean, according to his note: “[Cop30] invites COP Presidencies to develop the XXXX Roadmap to identify opportunities to accelerate the implementation of, and international cooperation and investment in NDCs, to close the gaps; convene a Coalition of Climate Ministers to inform the Roadmap to be published before COP31 and present findings at the annual high-level roundtable on pre-2030 ambition at COP31”.

This compromise will be regarded by some as kicking the can down the road, to Cop31 – and no one currently even knows where Cop31 will be held, as Australia and Turkey are still battling it out for the honour.

Where does a roadmap lead? Possibly to an action plan. The rest of do Lago’s note sets out some of the potential solutions to the other tricky issues, including an “action plan” on climate finance that would follow the Baku to Belem roadmap, or a “work programme” on similar issues, or in the case of trade, possibly round tables “on the nexus between trade and climate change, in 2026 and 2027”.

Roadmaps are an attractive instrument, for negotiations that appear stuck. But setting out a map is one thing. Persuading people to follow it is quite another. As Marina Silva told us: “When we have a terrain or environment that is quite grim, it is good that we have a map. But the map does not force us to travel, or to climb.”

A spectacular demonstration by tens of thousands of climate, nature and land activists in Belém this weekend has set the stage for the second week of COP30 negotiations, when organisers hope the energy from the streets can be channeled into the conference halls.

Monday and Tuesday mark the transition to the political phase of the negotiations, when ministers fly in to grapple with the issues that were too thorny for their bureaucrats to handle.

The climate conference got off to a flying start last week with a rapid agreement on the agenda, but then quickly became snarled up in dispute over four subjects: trade, transparency, finance, and how to address the shortfall between the emissions cuts planned by countries and those required to limit global heating to the 1.5C target of the Paris agreement.

Developing countries insist on much higher levels of climate finance from wealthy industrialised countries to assist with the energy transition and compensate for the loss and damage that is already being suffered as a result of global heating.

There have been more fruitful talks on a just transition for those affected by the move to a low-carbon economy, with a big push from the G77 group of countries, China and labour unions to adopt a Belém Action Mechanism on this topic.

For the first time, one draft mentions the “critical minerals” that will be needed for the energy transition. Other strong areas of debate were on adaptation and the need to address climate disinformation, which is recognised as a growing threat.

A fossil fuel phase out is not part of the official Cop30 agenda, but this fundamental issue has been bubbling away throughout the past week, and at a volume that has rarely been heard before. The Brazilian presidency is seeking a space within the process for talks on a roadmap “to accelerate the transition” with strong support from many global south nations and island states that are worst affected by the climate crisis. In an exclusive interview with The Guardian, Brazil’s environment minister Marina Silva said countries should have the “courage” to address the phase-out of fossil fuels, calling the drawing up of a roadmap for it an “ethical” response.

The need for urgency has never been more apparent. Numerous studies, unveiled in Belém, have shown the world has already failed to limit global heating to the Paris Agreement target of 1.5C, continues to put record amounts of warming gases such as methane and carbon dioxide into the atmosphere, and has started to pass dangerous tipping points in the Earth System. Over the past year, previous progress has been put into reverse, largely as a result of US president Donald Trump’s backtracking and trade tariffs that slow the spread of clean technologies. if “stated policies” are implemented as planned, the International Energy Agency revealed last week that it expects global warming to reach 2.5C by the end of this century, a tenth of a degree higher than last year’s forecast.

Brazil has yet to conclusively confirm or deny hopes that it will seek a concluding “cover text” to codify any progress achieved at this conference. If parties remain too far apart for that, the host may look for other ways to maintain momentum until next year’s Cop. Where that will take place is on the long list of unresolved issues. Australia and Turkey have been vying for hosting rights since 2022. If they fail to reach an agreement Cop31 could default to Bonn. Wherever it ends up, the host will be working against the clock to get ready with less than a year to go.

Belém faced similar doubts this time last year, but despite sky high accommodation costs and last-minute construction work, it has won many visitors over during the past week. The expected traffic chaos has not materialised. And many participants have expressed delight that indigenous groups and other elements of civil society have been given more space to participate and protest than the past three climate summits in authoritarian nations.

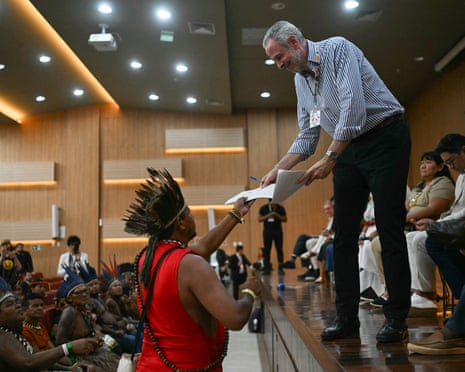

The “People’s Summit”, a series of civil society discussions that has been running in parallel to Cop30, wrapped up on Sunday with a declaration that capitalism was the root cause of the climate and nature crisis. Its demands, including an end to carbon credits and other market-based solutions, were presented to Brazilian environment minister Marina Silva and Cop30 president André Corrêa do Lago, who promised the statement would be noted in the proceedings of the conference.

Nothing remotely as radical is likely to be approved inside the official blue zone of the conference centre this week. But Monday will see several announcements and events related to forests and nature, including a new commitment to support land tenure for indigenous peoples and other traditional communities.

This is a significant step forward, particularly given this is the first summit of its type in the Amazon rainforest. But much more will be needed if forests and other natural biomes are to play a central role in restoring climate stability and planetary abundance.

While much of the attention this week will be on whether Cop30 can initiate the drawing of a roadmap away from the fossil fuel era, the Amazon ought to be as good a place as any to start thinking beyond wind farms and solar panels to where humanity might go next.

Hello, Ajit Niranjan here from Berlin – I’ll be hosting the liveblog this morning and my colleague Nina Lakhani will take over this afternoon.

We’re joined by a team of expert reporters on the ground, who’ll be bringing you the latest as the second week of the 30th UN climate summit kicks off.

Search

RECENT PRESS RELEASES

Related Post