Could A Bitcoin Miner Ever Become A Monopolist?

October 8, 2025

Early Facebook investor Peter Thiel once advised future startup founders to aim to build monopolies—and investors to buy them. By definition, a monopoly has market power: the ability to restrict quantities and raise prices. At the same time, Bitcoin mining is designed to be competitive. This raises a question: could a Bitcoin miner ever become a monopolist in the traditional economic sense, even with a major technological head start?

Monopolies typically emerge when a firm introduces a radical innovation that allows it to capture market share and earn above-normal profits. Recent examples include Google for search, Apple for the iPhone, Microsoft for office applications, and NVIDIA for GPUs. Each of these firms combined technological innovation with a wide economic moat, dominant market share, and high profitability—making them outstanding investments. True monopolies, however, are rare. More common are duopolies (like UPS and FedEx) oligopolies (like Bank of America, Wells Fargo, and JPMorgan), or fully competitive industries (airlines or restaurants). Still, with enough innovation, a monopoly could arise in almost any sector. So what if a new Bitcoin miner invented a machine that was ten times faster than all competitors? Would that firm become a monopolist? Let’s consider the game theory.

Suppose this miner—call it BitMonopoly—deployed this new hardware across its fleet. The performance of a mining rig is simple to measure: it hashes more quickly, expressed in terahashes per second. With a true 10× improvement, BitMonopoly would begin winning many of the blocks in the Bitcoin mining lottery. At the current difficulty of mining, the other miners in the market would still win some blocks. Block times would shrink. In the short run, BitMonopoly would capture many of the block rewards. Currently, each block yields a subsidy of 3.125 BTC plus transaction fees.

After roughly two weeks, however, the Bitcoin protocol would adjust difficulty upward. The adjustment is capped at a 4× change in either direction, meaning BitMonopoly would still dominate block production. After another two weeks, the protocol would adjust again. At this point, difficulty would be so high that only BitMonopoly could mine profitably. Legacy miners would effectively be shut out. At this level of mining difficulty, the Bitcoin protocol would then return block times to the ten-minute equilibrium, and BitMonopoly would capture 100% of market share and all block rewards.

How large is that revenue? At 3.125 BTC per block plus fees, multiplied across 2016 blocks per two weeks, or equivalently 52,416 blocks per year, annual gross revenue would equal 163,800 BTC. At today’s Bitcoin price of $115,000, that amounts to around $18.9 billion per year. Not bad.

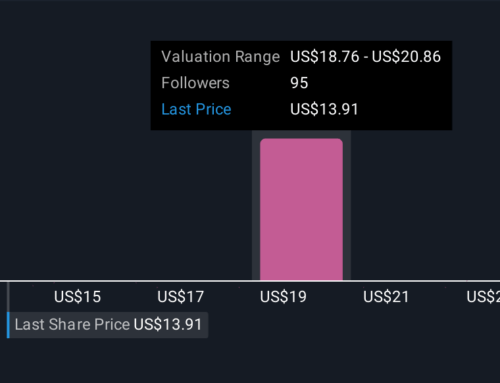

By any standard, BitMonopoly would be a monopoly: it would capture all profits in the market. Yet its profits are capped. The Bitcoin protocol constrains issuance and difficulty to stabilize block times, setting an upper bound on annual block rewards. That bound decreases every four years with each halving. Contrast this with corporations, whose market capitalization is theoretically unbounded. For example, NVIDIA—arguably the best example of a technological monopoly—has a market capitalization of $4.5 trillion and 2024 revenue of $130 billion. And Apple’s revenue is almost $400 billion last year, far exceeding the maximum possible revenue of BitMonopoly.

One open question remains: if the maximum upside from monopolizing Bitcoin mining is capped at $19 billion annually, does that limit the incentive to invent such a machine in the first place? The economic answer is yes. Entrepreneurs respond to incentives, and capped upside reduces motivation compared with uncapped opportunities in other markets. While $19 billion a year is substantial, it pales in comparison to the potential payoff from inventing the next smartphone or GPU. So from an antitrust perspective, Bitcoin mining poses little concern.

Search

RECENT PRESS RELEASES

Related Post