During the first Trump administration’s assault on climate initiatives, it was individual states that stepped up with policies to keep the momentum going on combating climate change.

The second Trump administration is now attempting to go after state actions too.

On a day the world’s attention was diverted by a massive meltdown of financial markets reeling from President Donald Trump’s tariffs, the president signed an executive order titled Protecting American Energy from State Overreach.

The order directs Attorney General Pam Bondi to seek out and potentially prosecute state and local actions or pending actions that “address ‘climate change’ or involving ‘environmental, social, and governance’ initiatives, ‘environmental justice,’ carbon or ‘greenhouse gas’ emissions, and funds to collect carbon penalties or carbon taxes.” It calls such actions “burdensome and ideologically motivated.”

Whether the goal is truly legal or an exercise in intimidation to get anticipatory compliance from states remains to be seen. But Governor Ned Lamont is having none of it when it comes to his climate legislative priorities and policies.

“We’re not going to change what we do,” he said Thursday, during a press briefing about Trump administration cutbacks the state is facing. “If I can mitigate some of the risk by changing some of the wording or titles — why not? I want to protect my kids. I want to protect the money we’re investing to keep you safe from flooding. But we’re not going to change who we are.”

While not mentioning Connecticut specifically, Trump’s executive order does call out states with policies similar to those Connecticut has or is considering. One is the climate change superfund legislation up for consideration this legislative session, which would penalize fossil fuel companies found to be contributing significantly to climate change and use the money collected to fund “climate mitigation, resiliency and adaptation projects.” The order specifies such funds already in place in Vermont and New York, calling them “extortion.”

The order also takes on carbon fees — specifically California’s cap-and-trade program, which is similar to the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative , RGGI, that Connecticut participates in along with the rest of New England and many mid-Atlantic states since its inception in 2009.

But the question of whether the executive order carries any legal heft gets an unambiguous response from environmental legal experts contacted by the Connecticut Mirror.

“No, no, no,” said Patrick Parenteau, professor emeritus at the Environmental Law Center at Vermont Law School. “It’s an email to Pam Bondi, saying, ‘Pam, see if you can find a way to challenge these states that are enacting all these laws and bringing all these lawsuits that I don’t like,” he said. “Let’s not give it any more gravitas than that. It’s an email.”

Brad Campbell, president of the Conservation Law Foundation and a former Environmental Protection Agency, EPA, regional administrator and trial attorney at the U.S. Department of Justice, called it “more political theater than it is law.”

“The executive order provides no legal rationale for why any of the categories of laws it’s attacking are unlawful or unconstitutional” he said. “I pity the DOJ attorney who has to come up with a legal basis for these types of challenges.”

The President has no authority to cancel a state program or tell a state to change its laws or cancel its regulations or anything like that. He can’t. He simply can’t do that.”

Michael Gerrard, Director of Sabin Center for Climate Change Law, Columbia University

“The EO is so outrageous that we cannot speculate as to legal theories that they may assert in challenging our state’s climate policies,” said Connecticut Attorney General William Tong in an email. He also said it had no legal effect. “We do not think there is any basis in law to attack individual state’s ability to make the necessary policy choices to protect their citizens and the environment.”

Michael Gerrard, director of the Sabin Center for Climate Change Law at Columbia Law School said: “The President has no authority to cancel a state program or tell a state to change its laws or cancel its regulations or anything like that. He can’t. He simply can’t do that.”

Gerrard and others said Congress can pass laws to change policy, but under current conditions is unlikely to get 60 votes in the Senate. The EPA can also issue regulations following all the required and lengthy rules to do so.

But if EPA or the White House were to tell Connecticut to stop doing what they’re doing, Gerrard said, “hopefully their response would be to say ‘no.’ And if EPA really insisted, hopefully the answer would be, ‘see you in court.’”

Amy Turner, director of the Cities Climate Law Initiative, also at the Sabin Center, said while the order is toothless, “what I worry a lot about are purple-er states and also local governments,” she said. “If a local policy is challenged in any one of the ways that might come about as a result of this exercise, it seems relatively likely that they would drop that policy. They don’t have the resources to engage in litigation.

“I’m quite worried about the chilling effect that this will have at the local level.”

Campbell thought it would likely “give some legislators pause in strengthening current law, particularly if it falls into, or arguably falls into, one of Trump’s targeted categories,” he said. “I think other state officials will worry that if they take bolder action in any of the areas this executive order targets, it’ll lead to funding cuts or other denials of federal resources or protections.”

Connecticut doesn’t appear cowed at this point.

In addition to Lamont, Charles Rothenberger, director of Connecticut government relations for Save the Sound, said he isn’t worried.

“We’re not going to repeal anything that we currently have on the books,” he said. “I don’t necessarily see anybody getting cold feet because of the noise coming out of Washington.”

Rep. Steve Winter, D-New Haven, and co-sponsor of the climate change superfund legislation, said he thought the executive order was designed as intimidation.

“I would hope that colleagues in the legislature would stay true to the values that make us who we are,” Winter said. “I think the overreach here really is at the federal level, whether it’s trying to dictate to the states what education policy looks like, [or]what climate change and resilience policy looks like.”

House Republican Leader Vincent Candelora, R-North Branford, who is an attorney, pointed to the 10th Amendment of the U.S. Constitution which says that whatever powers aren’t explicitly given to the federal government or withheld from the states are reserved to the states. Adherence to states rights has been the bedrock of the Republican party for decades, but critics contend the administration is abandoning that position .

“I think that the 10th Amendment could be under attack, based on what we’re seeing,” Candelora said.

“To the extent that the federal government wants to look at whether a state’s law is constitutional or not, I don’t necessarily have an issue with that,” he said, noting that, for instance, he has long felt Connecticut’s marijuana laws should have been pre-empted by federal law.

“When I look at this order, and I look at it through the lens of Connecticut, I don’t think Connecticut has done anything on an environmental level that is preempted by federal [law] and I would just be concerned if this was used in a more broad sense to go after states,” Candelora said.

Connecticut doesn’t have as many ambitious climate initiatives on the books as some of its neighbors like Massachusetts and New York, so there’s less for the Trump administration to go after.

The state has targets, including a zero carbon electric grid by 2040 , and a benchmark for the reduction of greenhouse gas emissions to reach 80% below 2001 levels by 2050. One of Connecticut’s two big climate bills this session seeks to strengthen that metric along with the bill’s renewable energy and energy efficiency provisions. The other focuses on resiliency. Both are largely comprised of provisions from legislation that failed over the last two sessions.

The state’s commitment to offshore wind has also waned, with one wind farm under construction and nothing more planned. That’s in contrast to neighboring states with more ambitious offshore wind goals and projects still awaiting permits.

The state did not place an official ban on gas hookups and is no longer using the strictest motor vehicle emissions permitted under the Clean Air Act.

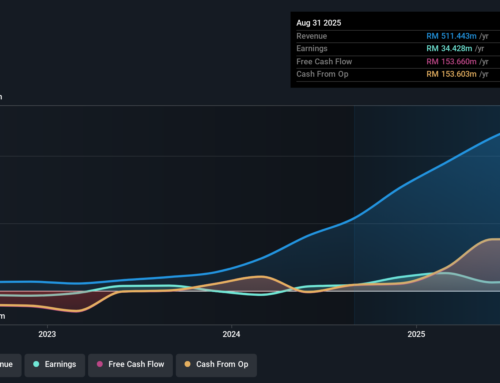

But a cap-and-invest program for the electric sector known as RGGI (pronounced reggie), which Connecticut has long championed, could provide a target. That program allows power plants over a certain size to essentially pay for the right to pollute. The allowances to do that are then sold through an auction, with proceeds going to the states for use in clean energy and energy efficiency projects.

Since RGGI started through 2022 (the last data available), Connecticut invested $288 million. About 70% has gone to energy efficiency through the Energy Efficiency Board, with 23% allocated to the Connecticut Green Bank. The rest is used for administration of the program.

Credit: Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative

“You can always file a lawsuit,” said Parenteau at Vermont Law School. “The real question is, what is Pam Bondi going to tell the president she has the capacity to do and what are the priorities to deploy her resources, which are shrinking by the day because she’s firing people, people are leaving DOJ, etc. So I think RGGI would rank way down somewhere at the very bottom of the list of targets.”

He said she’d be much more likely to go after California’s cap-and-trade.

“I’m not sure that RGGI preempts any federal laws or would be unconstitutional,” Candelora said. “I would think ultimately the state of Connecticut would prevail. And I just have a global concern that we are in general — and I use this across the board with both political parties — that we over-utilize the courts now.”

For Department of Energy and Environmental Protection Commissioner Katie Dykes, who has been Connecticut’s point-person on RGGI going back to her first position as deputy commissioner for energy at DEEP, the track record is clear — money saved and a 53% reduction in emissions.

“It’s on a solid foundation” she said.

John Moritz contributed reporting.