Cyclone Alfred is slowing – and that could make it more destructive. Here’s how climate change might have influenced it

March 6, 2025

Cyclone Alfred has now been delayed, as the slow-moving system stalls in warm seas off southeast Queensland. Unfortunately, the expected slow pace of the cyclone will bring even more rain to affected communities.

This is because it will linger for longer over the same location, dumping more rain before it moves on. Alfred’s slowing means the huge waves triggered by the cyclone will last longer too, likely making coastal erosion and flooding worse.

Cyclone Alfred is unusual – the first cyclone in half a century to come this far south and make expected landfall.

When unusual disasters strike, people naturally want to know what role climate change played – a process known as “climate attribution”. Unfortunately, this process takes time if you want details on a specific event.

We can’t yet say if Alfred’s unusual path and slow speed are linked to climate change. But climate change is driving very clear trends which can load the dice for more intense cyclones arriving in subtropical regions. These include the warm waters which fuel cyclones spreading further south, and cyclones dumping more rain than they used to.

So, let’s unpick what’s driving Cyclone Alfred’s behaviour – including the potential role of climate change.

Read more:

Cyclone Alfred is bearing down. Here’s how it grew so fierce – and where it’s expected to hit

Not necessarily climate linked: Alfred’s southerly path

Many cyclones make it as far south as Brisbane – but they’re nearly all far out at sea. Weather patterns mean most cyclones heading south are diverted to the east, where remnants can hit New Zealand as large extratropical storms.

The fact that Alfred is set to make landfall is very unusual. But we can’t yet definitively say this is due to climate change. Cyclones are steered by winds and weather patterns, and the Coral Sea’s complex weather makes cyclone paths here very hard to predict.

Alfred’s abrupt westward shift is due to a large region of high pressure to its south, which has pushed it directly towards heavily populated areas of southeast Queensland and northern New South Wales. These steering winds are not very strong, which is why Alfred is moving slowly.

In 2014, researchers showed cyclones are reaching their maximum intensity in areas further south in the southern hemisphere and north in the northern hemisphere than they used to. In 2021, researchers also found cyclones were reaching their maximum intensity closer to coasts, moving about 30 km closer per decade.

Climate link: Warmer seas

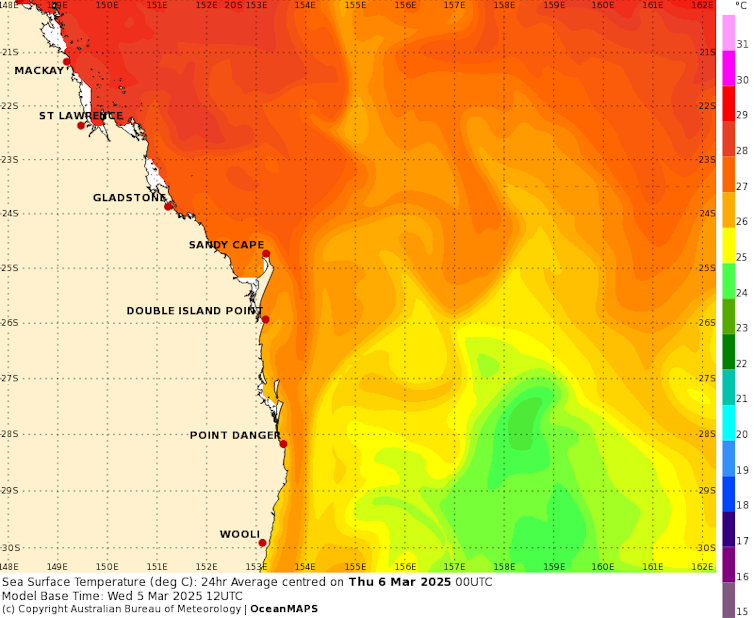

Cyclones typically need water temperatures of 26.5°C or more to form.

More than 90% of all extra heat trapped by greenhouse gas emissions is stored in the seas. The oceans are the hottest on record, and records keep falling. But normal seasonal variability and shifting ocean currents are still at work too, and we can get unusually warm waters without climate change as a cause.

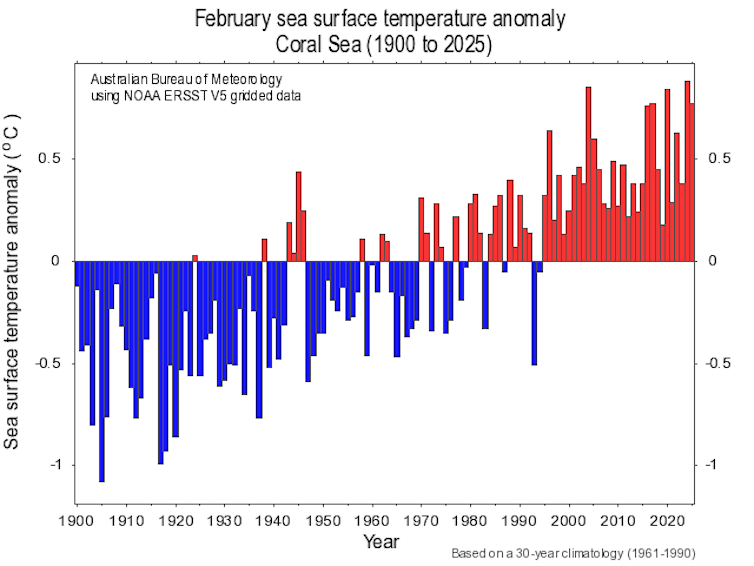

What we do know is that ocean temperatures around much of Australia have been unusually warm.

The northeastern Coral Sea, where Cyclone Alfred formed, experienced the fourth-hottest temperatures on record for February and the hottest on record for January.

Bureau of Meteorology, CC BY-NC-ND

We also know Australia’s southern waters are warming up too.

The energy available to power tropical cyclones in subtropical regions has also increased in recent decades, due largely to rising ocean temperatures.

Bureau of Meteorology, CC BY-NC-ND

Climate link: Fewer cyclones but more likely to be intense

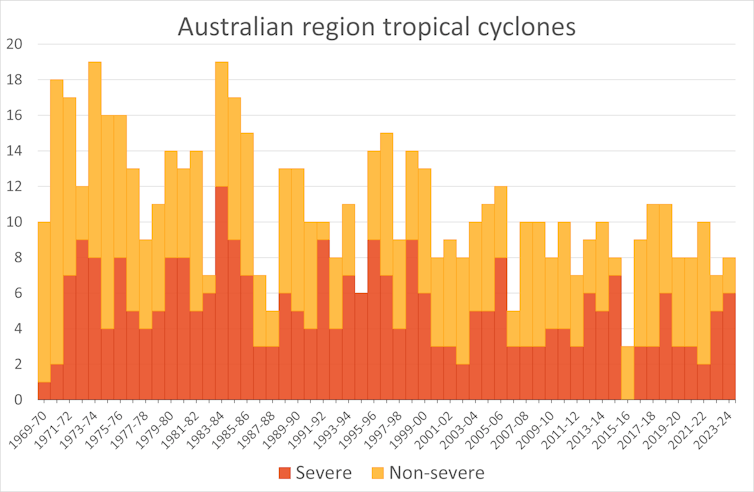

In the northern hemisphere, researchers have found a trend towards fewer cyclones over time. But of those which do form, a higher proportion are more intense.

It’s not fully clear if the same trend exists in the southern hemisphere, though we are seeing fewer cyclones forming over time.

This summer, eight tropical cyclones have formed in Australian waters. Six were classified as severe (category 3 and up). Historically, Australia has experienced a higher proportion of category 1 and 2 cyclones, which bring weaker wind speeds.

On average, we see about 11 cyclones form and 4-5 make landfall. There has been a downward trend in the number of cyclones forming in the Australian region in recent decades.

Bureau of Meteorology, CC BY-NC-ND

Climate link: Cyclones dumping more rain

The intensity of a cyclone refers to the speed of the wind and size of the wind-affected area.

But a cyclone’s rain field is also important. This refers to the area of heavy rain produced by storms when they’re at cyclone intensity and afterwards as they decay into tropical lows.

The rate of rainfall brought by cyclones in Australia isn’t necessarily increasing, but more cyclones are moving slowly, such as Alfred. This means more rain per cyclone, on average.

Rising ocean temperatures mean more water evaporates off the sea surface, meaning forming cyclones can absorb more moisture and dump more rain when it reaches land.

Why are cyclones slowing down? This is likely because air current circulation in the tropics has weakened. This has a clear link to climate change. Wind speeds have fallen 5 to 15% in the tropics, depending on where you are in the world. It’s hard to pinpoint the change clearly in our region, because the historic record of cyclone tracks isn’t very long.

For every degree (°C) of warming, rainfall intensity increases 7%. This is well established. But newer research is showing the rate may actually be double this or even higher, as the process of condensation releases heat which can trigger more rain.

Clear climate link: Bigger storm surges due to sea level rise

Sea levels are on average about 20 centimetres higher than they were before 1880.

When a cyclone is about to make landfall, its intense winds push up a body of seawater ahead of it – the storm surge. In low lying areas, this can spill out and flood streets.

Because climate change is causing baseline sea levels to rise, storm surges can reach further inland. Sea-level rise will also make coastal erosion more destructive.

Jason O’Brien/AAP

What should we take from this?

We can’t say definitively that climate change is behind Cyclone Alfred’s unusual track.

But factors such as rising sea levels, slower cyclones and warmer oceans are changing how cyclones behave and the damage they can do.

Over time, we can expect to see cyclones arriving in regions not historically affected – and carrying more rain when they arrive.

Search

RECENT PRESS RELEASES

Related Post