Development of a cannabis health literacy questionnaire: preliminary validation using the

July 24, 2025

- Research

- Open access

- Published: 24 July 2025

BMC Public Health

volume 25, Article number: 2539 (2025)

Abstract

As cannabis becomes more integrated into Canadian society for medical and non-medical purposes, public health efforts have aimed to enhance public awareness and knowledge of the potential risks associated with cannabis use. However, no validated or established method to measure cannabis health literacy exists, limiting the ability to evaluate the impacts of public awareness initiatives. We aimed to develop and preliminarily validate a cannabis health literacy questionnaire (CHLQ) designed to measure an individual’s knowledge, understanding and utilization of health and safety information related to cannabis.

The CHLQ was developed using existing health literacy domains and alcohol health literacy attributes as a framework. The questions were informed by extensive literature, item-response theory principles and input from stakeholders and people who use cannabis. The CHLQ includes four dimensions: knowledge of cannabis, knowledge of risks, understanding of associated risks and harms, and the ability to seek, access and use cannabis information. Adult participants were recruited through an online survey platform and social media. The questionnaire was refined and revised over three iterations using the Rasch analysis. Our preliminary validation process analyzed the CHLQ’s reliability and construct validity examining separation reliability, item difficulty, item fit statistics and unidimensionality.

A total of 1035 individuals across Canada completed our CHLQ. Each dimension of the CHLQ, had a well-distributed range of question difficulties. Across the four dimensions, item separation ranged from 9.93 to 17.29, and item reliability ranged from 0.99 to 1.00. Person separation ranged from 0.99 to 1.88, while person reliability ranged from 0.49 to 0.78. Most questions fit within the model, and unidimensionality was supported for all dimensions. Each dimension is scored separately with high scores indicating high knowledge or understanding for the respective domain. Raw scores for each dimension can be transformed to a linear Rasch score.

The CHLQ is a preliminary, multi-dimensional tool designed to measure cannabis health literacy for educational and research use. It demonstrates promising psychometric properties and provides an initial framework to inform public health efforts. Further validation in diverse population and settings is needed. The CHLQ provides foundation for future research, evaluation and public education efforts related to cannabis use.

Background

The Cannabis Act adopted a public health approach with non-medical cannabis legalization and highlighted the importance of informing the public about the potential risks and harms associated with cannabis use [1]. To protect public health and safety, the Canadian government has implemented several public education activities [2]. However, the effectiveness of these strategies in enhancing the public’s understanding and influencing behaviour remains unclear. There are existing cannabis assessment tools that primarily focus on screening and monitoring individuals who consume cannabis by measuring cannabis knowledge, cannabis use disorder, patterns of consumption, cannabis-related problems, and associated consequences [3,4,5,6]. Yet, an important aspect of cannabis public health and safety involves not only acquiring knowledge but also effectively using and applying this knowledge to make informed health-related decisions to help minimize harms and risks with cannabis use. Misunderstandings, lack of comprehension and misconception can contribute to potential negative impacts with cannabis use. Thus, it is imperative for individuals to possess the skills necessary to critically evaluate and apply cannabis-related health information in managing their decisions [7, 8].

Interacting with health information requires a wide range of skills, including reading, numeracy, communication, critical thinking, and social skills to make health-informed decisions [9]. The ability to effectively use health related information is known as health literacy [10, 11]. Health literacy refers to the skills and knowledge necessary to understand, evaluate and use health-related information to make informed health decisions [11]. An individual’s health literacy is both a prerequisite and outcome of health education, making it an essential factor in individual and public health interventions [12]. Poor health outcomes and risky health behaviours, including harmful substance use, have been associated with low health literacy [13,14,15]. The impact of health literacy is significant, as it influences an individuals’ ability to understand health and safety information, improve their health outcomes, minimize, and prevent health risks and make healthy lifestyle choices [16]. Furthermore, at a population level, health literacy plays a pivotal role in achieving better overall health outcomes, reducing healthcare costs and promoting greater health equity [16, 17].

Education emerges as a powerful tool that can significantly improve not only an individual’s health literacy, but the overall public health of a population [9]. Through clear, evidence-informed messaging, health promotion empowers individuals to make well-informed health decisions. To improve health literacy among populations, various tools have been developed and applied to different contexts. These include general health literacy tools [18,19,20,21] as well as tools for specific health conditions such as diabetes, liver disease, heart disease and COVID-19 [22,23,24,25]. However, there exists a gap in measuring health literacy in relation to substance use, such as alcohol and cannabis use. Few studies have measured alcohol health literacy using cross-sectional tools that lack reliability and validity [26,27,28]. To date, there has been a lack of reliable tools designed to measure individuals’ ability to assess, appraise and apply cannabis health information. In response to a gap for a comprehensive and reliable health literacy tool related to substance use, our study aimed to develop and validate a Cannabis Health Literacy Questionnaire (CHLQ). This self-reported measure is positioned within a health literacy framework, that extends beyond measuring cannabis health knowledge but also assess the skills required for applying this knowledge in ways that safeguard one’s health with cannabis use. Our aim in developing the CHLQ is to create a tool for educational and research purposes that provides insights into individuals’ cannabis health literacy. These insights could help inform and guide educational interventions aimed at enhancing cannabis health literacy among diverse populations.

Methods

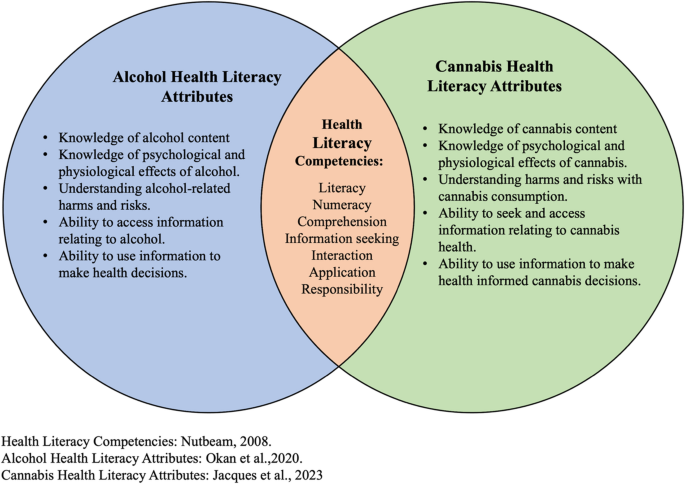

Our CHLQ was developed using Nutbeam’s Health Literacy Framework [10], which has been applied across various health contexts, including diabetes [29], cardiovascular diseases [30], measuring the quality of life [31], and alcohol use [32, 33]. The framework defines three core domains of health literacy: functional, interactive, and critical health literacy [10]. Our CHLQ adopted the functional and interactive health literacy domains of the Health Literacy Framework. The functional health literacy domain includes competencies such as literacy, numeracy, and comprehension. This domain guided our question generation to assess individual’s knowledge of cannabis content (e.g., ingredients, potency, dose) and evidenced-informed cannabis risks. Similarly, the interactive health literacy domain covers competencies such as information seeking, interaction, application, and responsibility, which influenced our decision to measure individuals understanding of cannabis risks and their ability to seek and use cannabis information. However, the critical health literacy domain in Nutbeam’s framework was not used for our CHLQ. The critical health literacy domain assesses advanced cognitive skills to critically analyze information through decision-making, health system navigation, and evaluation [34]. These skills, while important, involve a higher level of cognitive and reflective nature that goes beyond the scope of our questionnaire. Critical health literacy in the context of cannabis might only be relevant to consumers who engage deeply with cannabis-related issues and require advanced skills to critically analyze and reflect on their use. Our intention was for the CHLQ to be relevant to both consumers and non-consumers of cannabis. By focusing on functional and interactive health literacy, we aimed to ensure that our questionnaire would be more inclusive, providing valuable insights and practical knowledge to a wider audience, regardless of their cannabis use status.

Additionally, our CHLQ was informed by the alcohol health literacy framework [35]. Although this framework has not undergone validation, it discusses important multifaceted dimensions of health literacy when applied to alcohol, categorizing alcohol health literacy into functional, interactive, and critical domains with respective attributes. These attributes, crucial for understanding and engaging with alcohol-related health information, were thoughtfully adapted to the context of cannabis in our questionnaire. For example, where the alcohol health literacy framework emphasizes understanding the alcohol content and its physiological effects, our CHLQ measures the knowledge of cannabis content and the associated physiological and psychological risks. This adaption extends the framework’s application to the assessment of cannabis health literacy, enriching our tool’s ability to capture comprehensive dimensions in the context of substance use.

The alcohol health literacy framework also emphasizes the analysis of marketing and advertisements as measures for alcohol related critical health literacy [35]. Considering Canada’s stringent regulation on cannabis promotion [36], we are unable to measure the effect of promotion in cannabis health literacy. Thus, the domain was not applicable to our context [37] and was excluded from our CHLQ. Figure 1 provides a representation of the intersection of alcohol health literacy and the domains of our cannabis health literacy attributes.

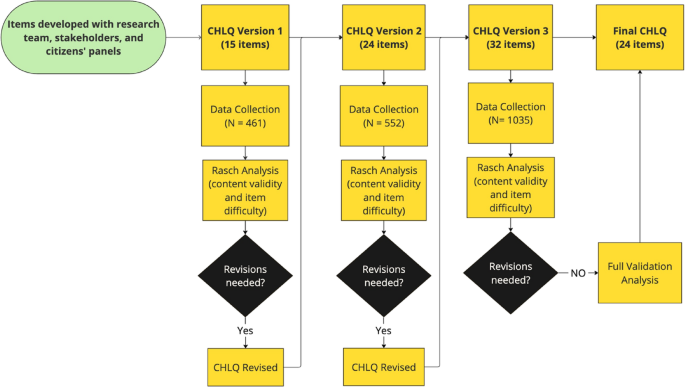

The items in the CHLQ were developed through two phases: initial item formulation and subsequent item refinement based on the Rasch analysis, a method that standardizes and validates research questionnaires [38].

For the first phase of the item generation, we consulted with our stakeholder and citizen advisory panels, that support our Cannabis Health Evaluation and Research Partnership (CHERP) program [39]. Our stakeholder panel comprised of members from both public and private sectors affected by cannabis legalization, such as representatives from provincial governments, cannabis retail, public health, addiction specialists, law enforcement, healthcare organizations and educational institutions. Our citizen advisory panel consisted of a diverse group of individuals from the general public who use cannabis for either medical or non-medical purposes, those who began using following its legalization and individuals who never consumed cannabis and have no experience with cannabis [40]. All members of both panels were consulted during the initial phase of item development to identify, determine, and create the topics and themes that would inform and address cannabis health literacy. Through these consultation meetings, panel members highlighted key cannabis topics to be measured such as knowledge of cannabis potency, physical and mental health effects, understanding risks, and the ability to access reliable health information. No formal consultations were conducted with the full advisory panel after the first pilot, however one or two members provided informal feedback on the subsequent iterations of the measure. Their input helped to assess the continued relevance and clarity of the revised items.

In developing the items and their content, we reviewed several existing health literacy tools including the European Health Literacy Survey (HLS-EU-Q47) [41], The Swiss Health Literacy Survey [21], the Mental Health Literacy Scale [42], and an Alcohol Health Literacy Survey [27], to examine their structure, style and question formulation. To inform the content of the items, we drew on discussions from our advisory panels and consulted the Lower-Risk Cannabis Use Guidelines (LRCUG) [43] to identify key information related to cannabis health knowledge being communicated to the public in Canada. Our item generation process was guided by item-response theory, with the goal of developing items that measure latent concepts (i.e., knowledge, understanding, and ability). Concurrently, we applied the Rasch measurement theory where items were designed to cover a spectrum of cannabis knowledge by difficulty levels [38]. Our aim was to include items ranging from common cannabis knowledge (easy difficulty) to uncommon/new cannabis knowledge (greater difficulty). Figure 2 shows the overall CHLQ item development process.

The items generated were organized into four main topics of information: 1.Knowledge of Cannabis, 2. Knowledge of Physical and Mental Health Risks, 3. Understanding Harms and Risks with Cannabis Use, and 4. The Ability to Seek, Access and Use of Cannabis Health Information. These topics formed the core dimensions of the CHLQ. Table 1 defines each dimension and aligns them with the functional or interactive health literacy domains.

We aimed for an overall readability level between grades six and eight to ensure accessibility for a broad population. We assessed the overall readability of each questionnaire version using the readability statistics assessment tool in Microsoft Word [44], and obtained an overall Flesh-Kincaid grade level of eight. Furthermore, we piloted our questionnaire within our research team, which consists of researchers in medicine, pharmacy, and graduate students (master’s and doctoral levels), to assess for errors, grammar, and readability.

In the second phase of the CHLQ item generation process, an iterative approach was adopted to refine and revise the questionnaire. Following the pilot of the initial questionnaire from the first phase, we utilized Rasch analysis to evaluate the questionnaires suitability in terms of item difficulty, and functionality [45]. Based on the results, modifications were made to the items, such as rewording questions for clarity, or adding new ones, and then piloted the revised questionnaire with a different sample. This iterative process led to the development of three different versions of the CHLQ, with the last iteration being selected as the final version of the CHLQ. Detailed results, including psychometric properties for the first two iterations are provided in our repository (https://doi.org/10.5683/SP3/WM4BDU) [46]. The third iteration of the CHLQ (final version) and its psychometric properties will be the focus of the results in this paper. Table 2 displays the details of each dimension in the third iteration of the CHLQ along with the response format, item numbers, and questions. Full version of the questionnaire can be found in Appendix A, with an answer key.

The CHLQ was distributed to three samples sequentially, with each sample receiving a subsequent iteration of the questionnaire. Refinements to the CHLQ were informed by the analysis process. Two of the samples’ data were collected using convenience sampling as part of a provincial cross sectional cannabis survey, and the third sample was obtained independently. All data for this study was collected between September 2022 – March 2023. Our target population consisted of adults of legal cannabis consumption age, encompassing both consumers, non-consumers, medical and non-medical cannabis users. This broad demographic was chosen to capture inclusive and comprehensive insight into cannabis health literacy, ensuring the questionnaire addresses the information and implications of cannabis use not just for individual well-being but also for the collective public health and safety. Participants were eligible to complete the questionnaire if they were 19 years of age and older and resided in Canada. Demographic characteristics such as age, biological sex, gender, educational level, and ethnicity were collected to describe respondents. For the first two iterations of the CHLQ, we recruited two adult population samples. The first sample was recruited through Angus Reid Forum, an online platform and community of thousands of adult Canadians who are invited to complete surveys based on a variety of topics via email solicitation [47]. The second sample was recruited through targeted newsletters and paid social media strategies. For these two samples, our questionnaire was piloted exclusively to Newfoundland and Labrador (NL) residents. Our questionnaire was integrated into a provincial cannabis survey designed for NL residents, thus serving as our pilot population samples through convenience sampling. Participants completed the questionnaire electronically on Qualtrics, a web-based survey platform [48]. For the final iteration of the CHLQ, our third sample was recruited again through Angus Reid Forum, and was open to Canadian subscribers from all provinces and territories to ensure a broader and more representative Canadian sample our final validation process. Unlike the previous samples, the final questionnaire was administered independently through Qualtrics and remained active until we reached our target of 1,000 eligible respondents. To ensure participants anonymity no personal identifying information was collected. Respondents from the Angus Reid forum were rewarded with points in their accounts as a token of their appreciation. Those who were recruited through newsletters and social media were given the opportunity to enter their names in a draw for a chance to win a monetary gift card after completing the questionnaire. To maintain the anonymity of their survey responses, participants were redirected to a separate survey link where they could enter their names for the draw.

As our study aimed to develop and conduct preliminary validation of a new measure to assess cannabis health literacy, we utilized the Rasch modeling to evaluate the psychometric properties of the CHLQ. The Rasch Model was selected for its interpretability and foundational use in early-stage instrument development [49], as well as its widespread application in health, education and social sciences questionnaires [50,51,52].

The Rasch model, a one-parameter logistic (1PL) IRT model, estimates item difficulty while assuming that all items (questions) have equal discrimination. In other words, it treats each item as equally effective in distinguishing between individuals at varying levels of the underlying trait – in this case, cannabis health literacy. The model calculates the probability that an individual will endorse (or correctly answer) an item based on the relationship between their latent ability (e.g., knowledge) and the item’s difficulty [45]. It hypothesizes that the easier the item is, the higher the probability of a person correctly endorsing that item, and the harder the item is, the lower the probability of correctly endorsing that item [53]. This relationship is quantified by mapping both item difficulty and person ability onto the same linear (logit) scale, allowing for comparisons [54]. For a detailed explanation of the Rasch model’s logic and equations, refer to the published literature [55,56,57].

In this study, person ability refers to an individual’s level of knowledge or understanding about cannabis, measured across four dimensions. Item difficulty reflects how challenging a given question is in assessing that knowledge. By using the Rasch model, which assumes equal discrimination across all items, each item is considered equally informative in distinguishing between individuals at different levels of ability. Given that cannabis knowledge is conceptualized as increasing along a single latent continuum, it was appropriate to assume that all items contribute equally to measuring the construct. This approach supports the development of a unidimensional, interpretable scale and enables generalizable inferences about item difficulty while maintaining a strong focus on construct validity and measurement integrity.

We conducted Rasch analysis separately for each CHLQ dimension across three iterations of the questionnaire to assess the functionality of the items. Two Rasch models were used based on the item type. The dichotomous Rasch model, appropriate for binary response items (correct or incorrect) [57,58,59] was applied to the Knowledge of Cannabis and Understanding Harms and Risks dimensions. The rating scale model, suitable for polytomous (e.g., Likert scale) responses [60], was used for the Knowledge of Risks and Seek, Access and Use Cannabis Health Information dimensions. In this model, higher response categories (e.g., Strongly Agree) represent greater agreement or endorsement of the latent trait being measured [49, 59].

To examine the psychometric validation properties of the CHLQ, each dimension was analyzed with four key psychometric properties (Table 3):

-

1.

Construct Validity was assessed using Wright Maps, a tool unique to Rasch modeling [61], to examine the distribution of person abilities and the ordering of item difficulties [62].

-

2.

Separation indices and reliability were examined to evaluate the scale’s ability to differentiate between items and individuals based on difficulty and ability levels [62,63,64].

-

3.

Unidimensionality and local independence were assessed to ensure that each dimension measured one latent construct (e.g., knowledge or ability) and that item responses within each dimension were independent of another (i.e., the response to one item did not depend on or influence the answer to another item – local independence) [65, 66].

-

4.

Item fit statistics, including INFIT and OUTFIT mean-square values, were used to assess whether each item aligned with the Rach model’s expectations. Specifically, whether the probability of correct response was consistent with the respondent’s estimated knowledge level [63, 67].

According the Rasch Analysis, a minimum sample size of 150 was needed to conduct the analysis and have 99% confidence in the item’s evaluation [70]. In alignment with Rasch guidelines [49, 53], any missing data or scores were coded as incorrect. Rasch models can robustly handle missing data due its ability to estimate parameters based on the pattern of responses provided by participants. The analysis treats non-responses to items as not applicable for the estimation of person ability and item difficulty parameters [53, 68, 71]. WINSTEPS, the statistical software utilized for the Rasch analysis, possess the capability to manage the missing data where they were excluded from calculations to ensure they did not influence the estimation process and maintain the integrity of the analysis [71]. WINSTEPS (v.5.3.3.1) [72] statistical software was used to conduct the Rasch analysis. IBM’s Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) software (v.28.0.1.1) [73] was used to analyze participant characteristics.

Results

The results presented in this paper focus on the third and final iteration of the CHLQ, emphasizing the development of the tool. Versions of the questionnaire from iterations one and two, along with their respective psychometric test results, are available in our repository (https://doi.org/10.5683/SP3/WM4BDU) [46].

A total of 1,035 participants (N = 1035) anonymously completed the third iteration of CHLQ with a response rate of 87%. As seen in Tables 4 and 524 participants identified as women (51%), the majority were of white ethnicity (80%), and 52% reported their highest education a college diploma or bachelor’s degree. The most prominent age group was the 30–39-year-old age group (26%). The performance of participants on the CHLQ will be discussed in future papers, as the primary focus of this paper is the development of the tool.

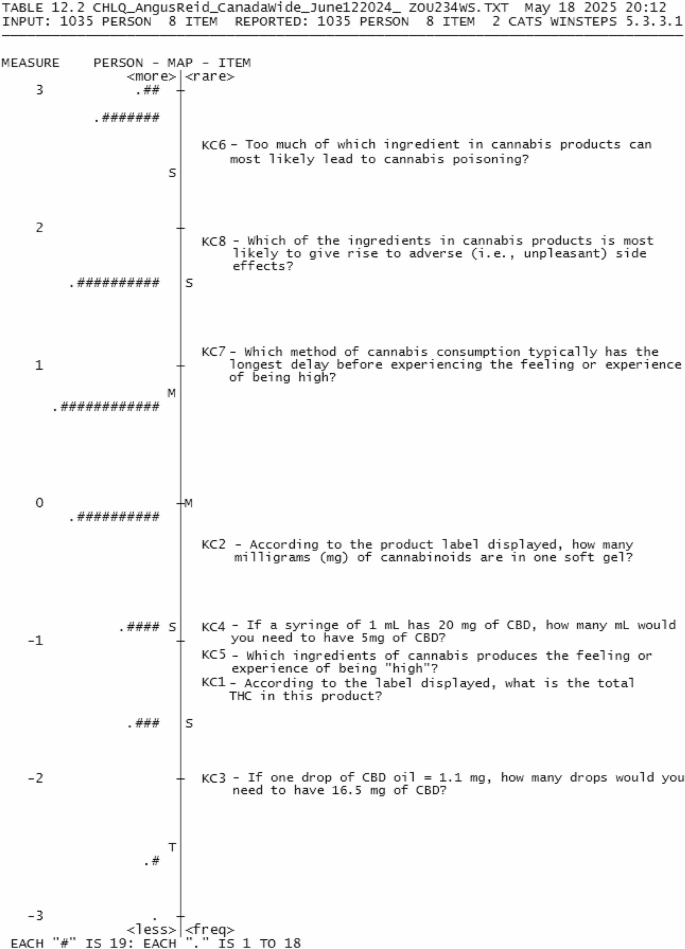

The Knowledge of Cannabis (KC) dimension is represented by items KC1- KC8 (Table 2). A dichotomous Rasch analysis was conducted for the KC dimension, where multiple-choice questions coded as correct (= 1) or incorrect (= 0). The KC initially contained 10 items assessing numeracy and literacy skills related to reading product labels, identifying potency levels and knowing cannabis ingredients. Two items were removed due to misfit and overlapping of item difficulty, meaning they were redundant. The final eight KC items (Table 5) ranged − 2.03 to 2.59 logits, where negative values indicate easier items and positive value indicate more difficulty items. The person score mean was 0.64 logits (SD = 0.97 logits) slightly exceeded the item mean, indicating this dimension was slightly easier for individuals to answer correctly (Fig. 3).

Rasch fit statistics was used to evaluate the fit of each question to the Rasch model of the dimension with INFIT and OUTFIT values between 0.5 and 1.5 considered acceptable (Table 3). Seven items in the KC dimension fit within the model, with KC8, slightly outfitting the dimension (≥ 1.5 logits). However, KC8 was retained as the outfit did not exceed a value greater than 2, indicating that the question is not degrading to the subscale [53]. The item separation and reliability (Table 6) was found to be satisfactory, with an item separation of 17.72 and reliability of 1.00. However, the person reliability and person separation were below criteria (values ≤ 1.50 and ≤ 0.5, respectively), indicating that different levels of respondent knowledge were not well distinguished due the high ability of our sample. Assumptions of unidimensionality were met, where the KC dimension ‘s variance was above 40% with an eigenvalue size < 2 in the first contrast in the unexplained variance.

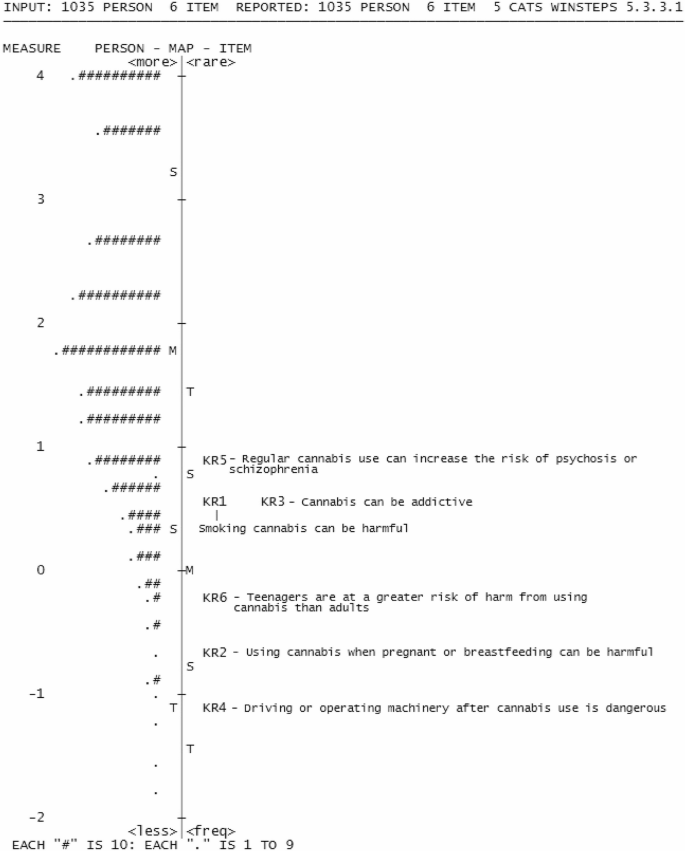

The Knowledge of Risks (KR) dimension includes KR1 – KR6 and uses a 5-point agreement Likert scale for responses (Table 2). A Rasch rating model was used for analysis. The KR dimension assessed literacy and comprehension with 12 items testing evidence informed risks with cannabis use. In an initial analysis, six redundant items were removed to increase the spread of difficult to easy items. The final six items in the KR dimension covered a range of −1.11 to 0.92 logits and with the person score mean above the item mean (1.76 logits, SD = 0.72) (Fig. 4), indicting our sample agreed with the items in this dimension.

All items in the KR dimension fit the model (Table 5), with acceptable item separation and reliability (14.63, 1.00, respectively). However, the person separation (1.32) was below criteria, and person reliability (0.64) for the KR dimensions was above criteria. Assumptions of unidimensionality were met, with a variance explained by the KR dimension at 48% and an eigenvalue of < 2 for the unexplained variance in the 1 st contrast (Table 6).

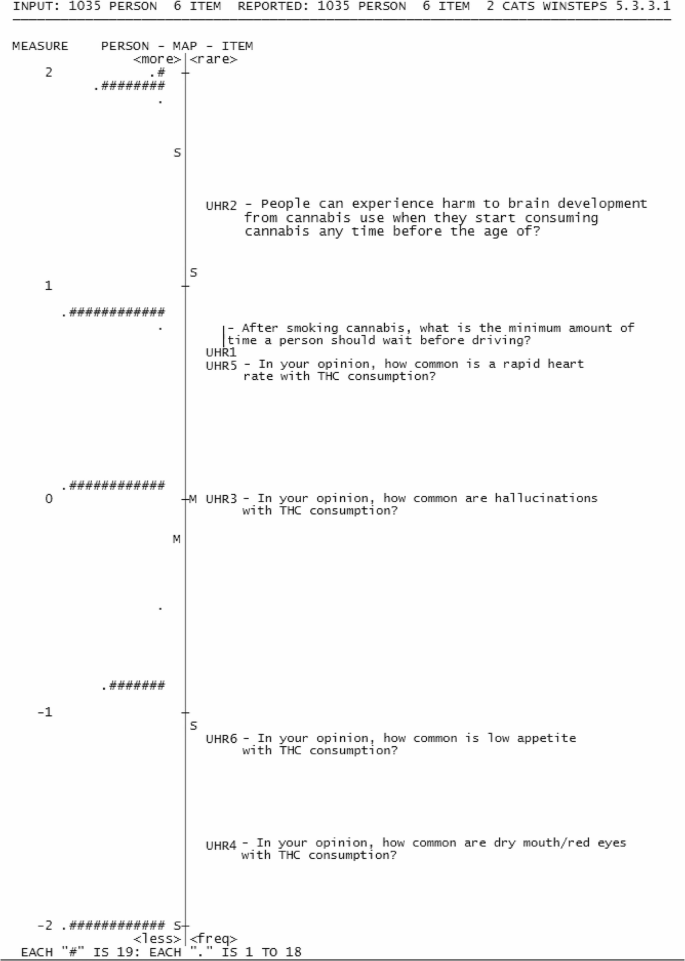

The understanding harms and risks (UHR) dimension is presented by items UHR1- UHR6 with the response options as multiple choice options, coded as correct and incorrect for the dichotomous Rasch analysis (Table 2). The dimension contained six items, that assesses literacy, information seeking and application skills by understanding the potential harms associated with cannabis use (Fig. 5). The UHR dimension covered a range of −3.45 to 3.37 logits with a respondent measure mean (−0.17 logits, SD = 1.17 logits) lower than the item means, suggesting that this dimension was more challenging for the respondents to answer correctly. Item UHR2 was seen to outfit the model (1.68 logits), suggesting this question does not fit within this dimension. However, the infit value for UHR2 (1.14 logits) was within acceptable range, suggesting that the question still contributed meaningfully to the overall measurement of this dimension [53]. The item separation (12.21) and reliability (0.99) were acceptable for this dimension; however, the person separation (0.99) and reliability (0.49) were below criteria. The variance explained by UHR dimension was below criteria (> 40%), and the eigenvalue in the first unexplained contrast was < 2.

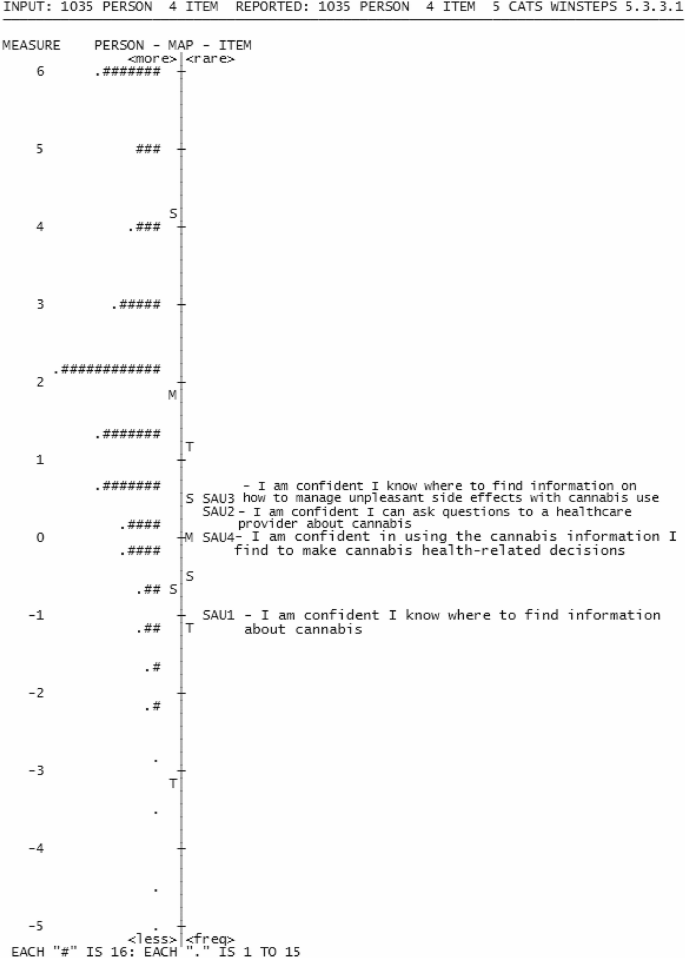

The Seek, Access and Use of Cannabis Health Information (SAU) dimension is represented by items SAU1-SAU4 (Table 2). The response options in this subscale are a 5-point agreement Likert scale, analyzed with the Rasch rating model. The SAU dimension contained four items, that assess information seeking, interaction with information by measuring the ability to interact with resources for cannabis health information. SAU dimension items ranged from − 0.92 to 0.51 logits, with items clustering at the average difficulty level (Fig. 6).

The mean respondent measure (1.79 logits, SD = 0.96 logits) was higher than the item mean value, indicating our sample mostly agreed to the items in this dimension. SAU2 exhibited both infit and outfit values above criteria (1.51 and 1.60 logits), suggesting a misalignment with the dimension’s intended construct [65, 66] (Table 5). The item separation (9.93) and reliability (0.99) met criteria. While person separation (1.88) and reliability (0.78) for (1.88,0.78) was acceptable (Table 6). The variance explained by the SAU dimension was 57.9% with an eigenvalue size < 2 in the first contrast in the unexplained variance, demonstrating unidimensionality was met.

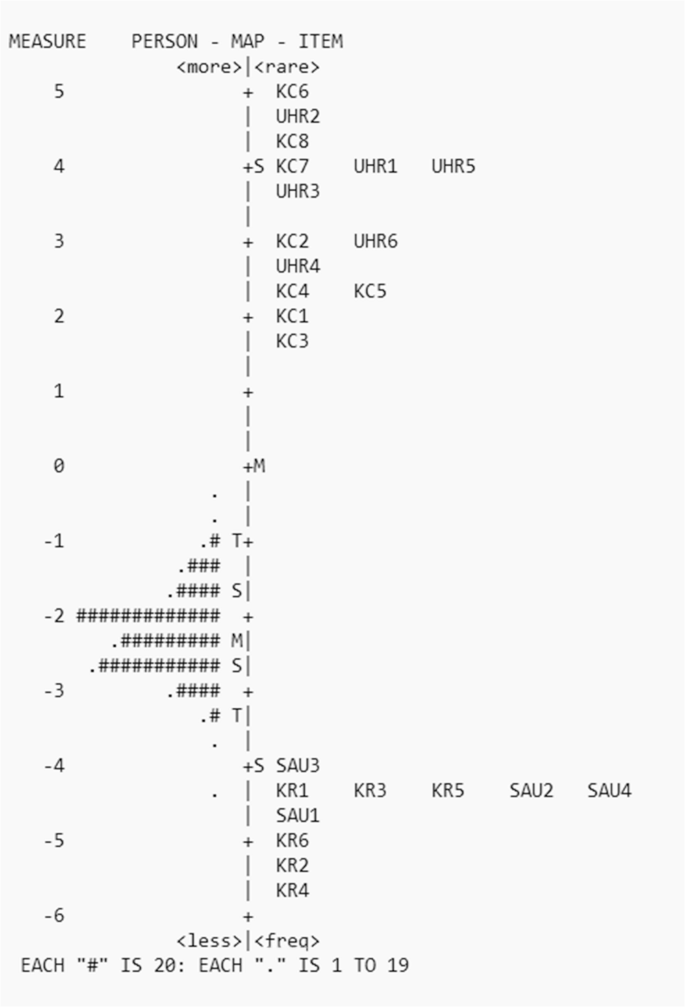

All items in the four dimensions (KC, KR, UHR and SAU) were assessed using the Rasch Partial Credit Model to evaluate their fit within a single model. The 24 items had difficulty levels ranging from − 5.72 to 4.93, with the mean person scores being − 2.23 (SD = 0.32), indicating individual’s low performance on the overall CHLQ (Fig. 7).

Item KR4 slightly misfit the model (INFIT > 1.5). The CHLQ composite accounted for 86.9% of variance with assumptions of unidimensionality not met (eigenvalue = 4.16), as expected. No significant item correlations (local independence) were observed (< 0.7). Item separation and reliability were acceptable (66.11, 1.00, respectively) with person separation and reliability not met (< 1.5 and < 0.5, respectively) (Table 6).

Discussion

Our Cannabis Health Literacy Questionnaire (CHLQ) comprises of four dimensions, assessing an individual’s knowledge of cannabis, knowledge of risks, understanding of the associated risks and harms, and their ability to seek, access, and utilize cannabis health information. Each dimension contains carefully curated questions that were developed and refined through a series of iterations, guided by psychometric validation using the Rasch analysis. To our knowledge, the CHLQ is among the first tool to offer a specialized approach to measuring cannabis health literacy.

Overall, each dimension of the CHLQ demonstrated good psychometric properties, providing insights into its measurement characteristics and reliability across its four dimensions. All four dimensions demonstrated an excellent range of question difficulties for our intended purpose, indicating effective question targeting [53]. This was further supported by high item separation-reliability values, confirming that the questions reliably measured their intended concepts [54]. Our analysis also identified that all four dimensions exhibited undimensionality. As an exploratory step, we evaluated the functionality of all items in the CHLQ as a composite. Our findings showed that scoring all items together as one CHLQ score accounted for high variance in item reliability. Unidimensionality was not met as expected due to the multiple dimensions of the CHLQ. For better utility, we suggest scoring each dimension separately. This approach better identifies the areas where individuals score well or need improvement rather than using a single composite CHLQ score. A conversion table for transforming raw scores of each dimension to Rasch linear scores is provided in Appendix B, allowing for comparisons across the four dimensions and for replication of the study.

Person separation and reliability for two out of the four dimensions fell below acceptable criteria. According the Rasch analysis, this suggests potential challenges in clearly distinguishing competency levels among individual for these two of our dimensions: (Knowledge of Cannabis, and Understanding Harms and Risks) [53, 68]. This indicates that the majority of our sample scored either highly or low in the two dimensions. If our participants had more varied abilities in knowledge and understanding, their scoring would improve person reliability. However, it is important to note that these results do not imply that the tool cannot be used, as our tool is not intended to be a diagnostic or a high-stake assessment tool but rather a descriptive measurement. Instead, the person separation and reliability can be further improved through strategies such as revising or adding more items, and ensuring we test the tool in a more diverse sample with varying knowledge levels, or exploring alternative scoring methods to help improve person reliability are suggested as per the Rasch Guidelines [64].

As our tool is exploratory and guided by health literacy frameworks, direct comparisons with other tools are not feasible. However, we have structured our tool similarly to existing health literacy assessments and aimed to evaluate concepts related to cannabis health knowledge, akin to other assessments in the literature. These concepts include measuring general cannabis health information, understanding cannabis harms and risks, assessing knowledge of cannabis label information, and gauging risk perceptions [6, 74, 75]. This alignment underscores the importance and relevance of the knowledge areas we measure, as they represent key aspects of cannabis health literacy. Through our validation, we have taken the first crucial steps towards establishing the reliability and effectiveness of our tool. While some tools in the literature have primarily focused on measuring cannabis knowledge among healthcare professionals [76,77,78], our CHLQ was specifically designed to be generic and user-friendly for researchers and the general public, even in its preliminary form. We ensured its accessibility by developing and validating the tool with a diverse sample of Canadian adults of legal cannabis consumption age, including consumers and non-consumers, for medical and/or non-medical purposes. This approach enabled us to include essential questions with a reading level of grade 6–8. This makes the tool valuable for understanding cannabis health literacy among a broader population, as it goes beyond knowledge assessment, but also assess the skills necessary for informed decision-making, and risk assessment. By examining psychometrics properties early in the tool’s development, we positioned the CHLQ to offer a reliable means of assessing cannabis health literacy across population at a point in time, enabling comparisons, evaluations of public education efforts and identification of knowledge gaps.

Our questionnaire also follows health literacy and alcohol health literacy frameworks. Nutbeam’s health literacy framework [10], highlights the importance of clearly defining the content and context of the questionnaire for obtaining the most accurate measurement of health literacy. The format and structure of our CHLQ enables the measurement of different aspects and dimensions of cannabis health literacy. The functional domain assesses the practical knowledge and skills required for informed decision-making regarding cannabis use, while the interactive domain delves into the ability to engage with and interpret cannabis health information in various contexts. For instance, our CHLQ introduces a higher level of complexity than other measures through questions that require participants to calculate THC content, comprehend cannabinoid dosage, and evaluate the risks linked to cannabis use mirroring real world challenges. This tailored approach ensures the CHLQ clearly defines concepts of cannabis health and safety information, readying it for applicability to broader health education interventions [35]. This further strengthens the CHLQ as a pioneering tool for comprehensive cannabis health literacy assessment and supports the development of health literacy frameworks in substance-related domains. It also positions the CHLQ for future development as a diagnostic tool or as a tool that can be used to assess behaviours related to cannabis health literacy.

Our study, while offering insights on cannabis health literacy measurement, is not without limitations. First, our study had a substantial sample size (N = 1035) for psychometric analyses, but it’s important to acknowledge that our sample is not fully representative of adults in Canada seeking and interacting with cannabis information. The difficulty of the CHLQ items may have been influenced by our sample characteristics, particularly the high proportion of highly educated participants, which could affect the generalizability of the questionnaire and item difficulty estimates. Additionally, our items were developed based on the available evidence at the time; however, we acknowledge this area of research continues to evolve.

While our questions were intentional in what they were measuring (i.e., comprehension and numeracy skills) additional analysis is needed to examine how education level and other demographic factors influence responses. Additionally, the high knowledge level of our sample likely influenced our person reliability results, where we are not able to classify people into groups based on their ability for two out of the four dimensions. This limitation may affect both item functioning and person reliability estimates. Future studies should assess whether the tool performs similarly in populations with more varied cannabis experience to better evaluate person reliability and more accurately establish competency levels.

Second, the self-reported nature of the questionnaire introduces the possibility of social desirability bias [79] and response bias [80], which may impact accuracy and reliability of responses [81]. The CHLQ was administered exclusively online through an online forum with some incentives. To address this limitation, future studies could explore alternative methods of administering the CHLQ, such as telephone interviews or in-person questionnaire administration, similar approached used in other health literacy tools.

Third, while the present study rigorously examined the psychometric properties of the CHLQ (item difficulty, reliability, fit statistics, unidimensionality, and construct validity), it acknowledges the absence of test-retest reliability [82] and convergent validity [83] analyses as a limitation. While there are no direct cannabis health literacy tools available for comparison, the CHLQ is situated within the broader context of general health literacy and alcohol health literacy assessments. Future research is needed to evaluate these unexamined aspects of validity.

Lastly, we used the 1PL Rasch model for its simplicity and interpretability in this initial stage of instrument development. We acknowledge that our sample size would support the use of more complex IRT models. The decision to use the Rasch model was driven by the desire to avoid overfitting data and maintain a theory-grounded foundation for the questionnaire. Future analyses may consider employing 2 -or 3- parametric logistical models to further explore item discrimination and guessing behaviour in greater depth. Overall, future research is warranted to further explore these unexamined aspects of validity and to replicate the findings of the present study in more diverse populations.

The authors of this study plan to conduct sub-group analyses to examine the performance of the CHLQ across different demographic groups, including age, gender, education level, and cannabis use history. Additional analysis beyond the scope of this initial development has been conducted which will be reported in a follow up study. These analyses will provide valuable insights into potential variations in cannabis health literacy among diverse populations. Additionally, we intend to continue the validation process of the tool by consulting with experts in the field, further strengthening its validity and reliability. These ongoing efforts will contribute to a more comprehensive and skillful understanding of individuals’ cannabis health literacy in Canada and support the refinement of the CHLQ.

Conclusion

The development and preliminary validation process of the Cannabis Health Literacy Questionnaire (CHLQ) has been guided by a robust health literacy framework ensuring we measure individuals’ ability to apply cannabis factual information in decision-making regarding cannabis use. This unique approach coupled with a rigorous validation process through the Rasch analysis, positions the CHLQ as a potentially valuable tool for assessing individuals’ cannabis health literacy. Ultimately, the CHLQ presents a compelling and potentially impactful instrument to inform public health strategies related to cannabis use. The CHLQ is not just a measurement tool but a starting point for broader dialogue, research, and policy development around cannabis-related health literacy. Future research is warranted to further examine its validity and reliability across diverse populations and settings.

Data availability

The data described in this article can be freely and openly accessed at Memorial University Dataverse: https://doi.org/10.5683/SP3/WM4BDU. Additional Data is also provided within the manuscript and supplementary information files.

Abbreviations

- CHERP:

-

Cannabis Health Evaluation and Research Partnership

- CHLQ:

-

Cannabis Health Literacy Questionnaire

- HLS-EU-Q47:

-

European Health Literacy Survey

- IRT:

-

Item-Response Theory

- KC:

-

Knowledge of Cannabis

- KR:

-

Knowledge of Risks

- LRCUG:

-

Lower-Risk Cannabis Use Guidelines

- NL:

-

Newfoundland and Labrador

- UHR:

-

Understanding Harms and Risks

- SAU:

-

Seek, Access and Use Cannabis Health Information

- SD:

-

Standard Deviation

References

-

Government of Canada. Consolidated federal laws of Canada, Cannabis Act [Internet]. 2023 [cited 2023 Oct 6]. Available from: https://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/C-24.5/

-

Health Canada. Cannabis Public Education Activities [Internet]. 2018 [cited 2023 May 26]. Available from: https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/news/2018/06/cannabis-public-education-activities.html

-

Adamson SJ, Kay-Lambkin FJ, Baker AL, Lewin TJ, Thornton L, Kelly BJ, et al. An improved brief measure of cannabis misuse: the Cannabis use disorders identification Test-Revised (CUDIT-R). Drug Alcohol Depend. 2010;110:137–43.

-

Knapp AA, Babbin SF, Budney AJ, Walker DD, Stephens RS, Scherer EA, et al. Psychometric assessment of the marijuana adolescent problem inventory. Addict Behav. 2018;79:113–9.

-

Bastiani L, Potente R, Scalese M, Siciliano V, Fortunato L, Molinaro S. Chapter 100 – The Cannabis Abuse Screening Test (CAST) and Its Applications. In: Preedy VR, editor. Handbook of Cannabis and Related Pathologies [Internet]. San Diego: Academic Press; 2017 [cited 2023 May 26]. pp. 971–80. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B9780128007563001174

-

Bayat A, Mansell H, Taylor J, Szafron M, Mansell K. The development of a Cannabis knowledge assessment tool (CKAT). PLoS ONE. 2023;18(9):e0291113.

-

Ecker UKH, Lewandowsky S, Cook J, Schmid P, Fazio LK, Brashier N, et al. The psychological drivers of misinformation belief and its resistance to correction. Nat Rev Psychol. 2022;1(1):13–29.

-

Lewandowsky S, Ecker UKH, Cook J. Beyond misinformation: Understanding and coping with the Post-Truth. Era J Appl Res Memory Cognition. 2017;6(4):353–69.

-

Sørensen K, Van den Broucke S, Fullam J, Doyle G, Pelikan J, Slonska Z, Brand H; (HLS-EU) Consortium Health Literacy Project European. Health literacy and public health: a systematic review and integration of definitions and models. BMC Pub Health. 2012;12:80. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-12-80.

-

Nutbeam D. The evolving concept of health literacy. Soc Sci Med. 2008;67(12):2072–8.

-

Berkman ND, Davis TC, McCormack L. Health literacy: what is it? J Health Communication. 2010;15(SUPPL 2):9–19.

-

Ratzan SC. Health literacy: communication for the public good. Health Promot Int. 2001;16(2):207–14.

-

Lee YM, Yu HY, You MA, Son YJ. Impact of health literacy on medication adherence in older people with chronic diseases. Collegian. 2017;24(1):11–8.

-

Wolf MS, Gazmararian JA, Baker DW. Health literacy and health risk behaviors among older adults. Am J Prev Med. 2007;32(1):19–24.

-

Dewalt DA, Berkman ND, Sheridan S, Lohr KN, Pignone MP. Literacy and health outcomes: a systematic review of the literature. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19(12):1228–39.

-

Berkman ND, Donahue K, Halpern D, Sheridan SL, Donahue KE, Halpern DJ et al. Low health literacy and health outcomes: an updated systematic review Article in annals of internal medicine. Annals Intern Med [Internet]. 2011;155(2). Available from: https://www.annals.org.

-

Nutbeam D. Health literacy as a public health goal: a challenge for contemporary health education and communication strategies into the 21st century. Health Promot Int. 2000;15(3):259–67.

-

Hahn RA, Truman BI. Education improves public health and promotes health equity. Int J Health Serv. 2015;45(4):657–78.

-

Davis TC, Long SW, Jackson RH, Mayeaux EJ, George RB, Murphy PW, et al. Rapid estimate of adult literacy in medicine: a shortened screening instrument. Fam Med. 1993;25(6):391–5.

-

Parker RM, Baker DW, Williams MV, Nurss JR. The test of functional health literacy in adults: a new instrument for measuring patients’ literacy skills. J Gen Intern Med. 1995;10(10):537–41.

-

Wang J, Thombs BD, Schmid MR. The Swiss health literacy survey: development and psychometric properties of a multidimensional instrument to assess competencies for health. Health Expect. 2014;17(3):396–417.

-

Ishikawa H, Takeuchi T, Yano E. Measuring functional, communicative, and critical health literacy among diabetic patients. Diabetes Care. 2008;31(5):874–9.

-

Magnani JW, Mujahid MS, Aronow HD, Cené CW, Dickson VV, Havranek E, et al. Health literacy and cardiovascular disease: fundamental relevance to primary and secondary prevention: A scientific statement from the American heart association. Circulation. 2018;138(2):e48–74.

-

Okan O, Bollweg TM, Berens EM, Hurrelmann K, Bauer U, Schaeffer D. Coronavirus-related health literacy: A cross-sectional study in adults during the COVID-19 infodemic in Germany. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(15):1–20.

-

Gulati R, Nawaz M, Pyrsopoulos NT. Health literacy and liver disease. Clin Liver Dis (Hoboken). 2018;11(2):48–51.

-

Rolova G, Gavurova B, Petruzelka B. Exploring health literacy in individuals with alcohol addiction: A mixed methods clinical study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(18):1–20.

-

Barnard KD, Dyson P, Sinclair JMA, Lawton J, Anthony D, Cranston M, et al. Alcohol health literacy in young adults with type 1 diabetes and its impact on diabetes management. Diabet Med. 2014;31(12):1625–30.

-

Dow L, Poag D, Thomson E. Evaluating Undergraduate Alcohol Health Literacy and Education Efficacy. SSRN Journal [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2023 May 26]; Available from: https://www.ssrn.com/abstract=3604755

-

Schillinger D, Grumbach K, Piette J, Wang F, Osmond D, Daher C, et al. Association of health literacy with diabetes outcomes. JAMA. 2002;288(4):475–82.

-

Kanejima Y, Shimogai T, Kitamura M, Ishihara K, Izawa KP. Impact of health literacy in patients with cardiovascular diseases: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Patient Educ Couns. 2022;105(7):1793–800.

-

Zheng M, Jin H, Shi N, Duan C, Wang D, Yu X, et al. The relationship between health literacy and quality of life: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2018;16(1):201.

-

Rolova G, Gavurova B, Petruzelka B. Health literacy, self-perceived health, and substance use behavior among young people with alcohol and substance use disorders. Int J Environ Res Pub Health. 2021;18(8):4337.

-

Anderson P, Rehm J. Evaluating alcohol industry action to reduce the harmful use of alcohol. Alcohol Alcohol. 2016;51(4):383–7.

-

Chinn D. Critical health literacy: A review and critical analysis. Soc Sci Med. 2011;73(1):60–7.

-

Okan O, Rowlands G, Sykes S, Wills J. Shaping alcohol health literacy: A systematic concept analysis and review. Health Lit Res Pract. 2020;4(1):e3–20.

-

Government of Canada. Cannabis Regulations Règlement sur le cannabis. 2018; Available from: https://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/PDF/SOR-2018-144.pdf

-

Steckelberg A, Hülfenhaus C, Kasper J, Rost J, Mühlhauser I. How to measure critical health competences: development and validation of the critical health competence test (CHC test). Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2009;14(1):11–22.

-

Bond T. Applying the Rasch model: fundamental measurement in the human sciences, third edition. 3rd ed. New York: Routledge; 2015. p. 406.

-

Cannabis Health Evaluation and Research Partnership. Memorial University of Newfoundland. [cited 2023 Oct 6]. Cannabis Health Evaluation and Research Partnership| School of Pharmacy. Available from: https://www.mun.ca/pharmacy/research/cherp/

-

Cannabis Health Evaluation Research Partnership. Helping to develop cannabis policy inNL: Prioritizing Public Health and Safety. Evidence to Policy Symposium, March 22, 2023 Summary Report. Memorial University of Newfoundland and Labrador. St. John’s, NL: Canada; 2023. https://www.mun.ca/pharmacy/media/production/memorial/academic/school-of-pharmacy/media-library/research/CHERP%20Symposium%20WWH%20Report.pdf.

-

Sørensen K, Van den Broucke S, Pelikan JM, Fullam J, Doyle G, Slonska Z, Kondilis B, Stoffels V, Osborne RH, Brand H; HLS-EU Consortium. Measuring health literacy in populations: illuminating the design and development process of the European Health Literacy Survey Questionnaire (HLS-EU-Q). BMC Pub Health. 2013;13:948. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-13-948.

-

O’Connor M, Casey L. The mental health literacy scale (MHLS): A new scale-based measure of mental health literacy. Psychiatry Res. 2015;229(1–2):511–6. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0165178115003698.

-

Fischer B, Robinson T, Bullen C, Curran V, Jutras-Aswad D, Medina-Mora ME, et al. Lower-Risk Cannabis use guidelines (LRCUG) for reducing health harms from non-medical cannabis use: A comprehensive evidence and recommendations update. Int J Drug Policy. 2022;99:103381–103381.

-

Paasche-Orlow MK, Taylor HA, Brancati FL. Readability standards for informed-consent forms as compared with actual readability. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(8):721–6.

-

Andrich D, Marais I. A Course in Rasch Measurement Theory: Measuring in the Educational, Social and Health Sciences [Internet]. Singapore: Springer Nature Singapore; 2019 [cited 2023 May 26]. (Springer Texts in Education). Available from: https://link.springer.com/https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-7496-8

-

Donnan J, Jaques Q, Bishop L, Howells R, Najafizada M. Cannabis Health Literacy Rasch Validation Data [Internet]. Borealis; 2024 [cited 2024 Jul 26]. Available from: https://borealisdata.ca/dataset.xhtml?persistentId=doi:https://doi.org/10.5683/SP3/WM4BDU

-

Angus Reid. Angus Reid. [cited 2023 May 26]. Angus Reid| Consumer research you can trust within 48 hours. Available from: https://www.angusreid.com/

-

2023 [cited 2023 Oct 6]. Qualtrics [Internet], Qualtrics XM. // The Leading Experience Management Software. Available from: https://www.qualtrics.com/

-

Bond T. Applying the Rasch Model: Fundamental Measurement in the Human Sciences. Third Edition (3rd ed.). Routledge; 2015. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315814698.

-

Artino AR, La Rochelle JS, Dezee KJ, Gehlbach H. Developing questionnaires for educational research: AMEE guide 87. Med Teach. 2014;36(6):463–74.

-

Kishore K, Jaswal V, Kulkarni V, De D. Practical guidelines to develop and evaluate a questionnaire. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2021;12(2):266–75.

-

Arora C, Sinha B, Malhotra A, Ranjan P. Development and validation of health education tools and evaluation questionnaires for improving patient care in lifestyle related diseases. J Clin Diagn Res. 2017;11(5):JE06–9.

-

Boone WJ, Staver JR, Yale MS. Rasch Analysis in the Human Sciences [Internet]. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands; 2014 [cited 2023 May 26]. Available from: https://link.springer.com/https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-6857-4

-

Boone WJ. Rasch Analysis for Instrument Development: Why, When, and How? CBE Life Sci Educ. 2016 Winter;15(4):rm4. https://doi.org/10.1187/cbe.16-04-0148.

-

Mellenbergh GJ, Vijn P. The Rasch model as a loglinear model. Appl Psychol Meas. 1981;5(3):369–76.

-

Wright BD. Comparing Rasch measurement and factor analysis. Struct Equ Model. 1996;3(1):3–24.

-

Andrich D, Marais I. A Course in Rasch Measurement Theory: Measuring in the Educational, Social and Health Sciences [Internet]. Singapore: Springer Nature; 2019. (Springer Texts in Education). Available from: https://link.springer.com/10.1007/978-981-13-7496-8.

-

Masters GN. A Rasch model for partial credit scoring. Psychometrika. 1982;47(2):149–74.

-

Wright BD. Rasch.Org. 1998 [cited 2024 Feb 28]. Model selection: Rating Scale Model (RSM) or Partial Credit Model (PCM)? Available from: https://www.rasch.org/rmt/rmt1231.htm

-

Andrich D. A rating formulation for ordered response categories. Psychometrika. 1978;43(4):561–73.

-

Cook DA, Beckman TJ. Current concepts in validity and reliability for psychometric instruments: theory and application. Am J Med. 2006;119(2):166..e7-166.e16.

-

Smith Jr. EV. Evidence for the reliability of measures and validity of measure interpretation: A Rasch measurement perspective. J Appl Meas. 2001;2:281–311.

-

Smith AB, Rush R, Fallowfield LJ, Velikova G, Sharpe M. Rasch fit statistics and sample size considerations for polytomous data. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2008;8(1):33.

-

Linacre J. Reliability and separation measures [Internet]. 2019. Available from: https://www.winsteps.com/winman/reliability.htm

-

Brentari E, Golia S, Brentari E, Golia S. Unidimensionality in the Rasch model: how to detect and interpret Rasch Measurement View project Behrens-Fisher Problem View project. 2007; Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/46553452

-

Linacre J, Dimensionality. PCAR contrasts & variances [Internet]. 2019. Available from: https://www.winsteps.com/winman/principalcomponents.htm

-

Wright B, Linacre J. Reasonable mean-square fit values. Rasch Meas Trans. 1994;8:3.

-

Linacre J. A user’s guide to winsteps ministep Rasch-model computer programs. (5-50). 2012. https://Winsteps.com.

-

Fan J, Bond T. Applying Rasch measurement in language assessment: Unidimensionality and local independence. In V. Aryadoust & M. Raquel (Eds.), Quantitative data analysis for language assessment: Volume I: Fundamental techniques (pp. 83–102). Routledge; 2019.

-

Linacre J. Sample Size and Item Calibration or Person Measure Stability [Internet]. 1994 [cited 2023 Oct 28]. Available from: https://www.rasch.org/rmt/rmt74m.htm

-

Waterbury G. Missing data and the Rasch model: the effects of missing data mechanisms on item parameter Estimation. J Appl Meas. 2019;20:1–12.

-

Linacre M. WINSTEPS Rasch Software – Winsteps Facets [Internet]. 2023 [cited 2023 May 26]. Available from: https://www.winsteps.com/winsteps.htm

-

SPSS Statistics| IBM [Internet]. [cited 2023 May 26]. Available from: https://www.ibm.com/products/spss-statistics?utm_content=SRCWW%26;p1=Search&p4=43700050436737811%26;p5=e%26;gclid=CjwKCAjwscGjBhAXEiwAswQqNOHqX1RF-plwPnut2EDDrlIEy7k81CCP6eKWvYlRV_gV0IHS5CQuuxoCIhQQAvD_BwE%26;gclsrc=aw.ds

-

Leos-Toro C, Fong GT, Meyer SB, Hammond D. Cannabis health knowledge and risk perceptions among Canadian youth and young adults. Harm Reduct J. 2020;17(1):54.

-

Kruger DJ, Mokbel MA, Clauw DJ, Boehnke KF. Assessing health care providers’ knowledge of medical Cannabis. Cannabis Cannabinoid Res. 2022;7(4):501–7.

-

King DD, DeCarlo M, Mylott L, Yarossi M. Cannabis knowledge gaps in nursing education: pilot testing cannabis curriculum. Teach Learn Nurs. 2023;18(4):474–9.

-

Szaflarski M, McGoldrick P, Currens L, Blodgett D, Land H, Szaflarski JP, et al. Attitudes and knowledge about cannabis and cannabis-based therapies among US neurologists, nurses, and pharmacists. Epilepsy Behav. 2020;109:107102.

-

Kansagara D, Morasco BJ, Iacocca MO, Bair MJ, Hooker ER, Becker WC. Clinician knowledge, attitudes, and practice regarding cannabis: results from a National veterans health administration survey. Pain Med. 2020;21(11):3180–6.

-

Mondal H, Mondal S. Social desirability bias: A confounding factor to consider in survey by self-administered questionnaire. Indian J Pharmacol. 2018;50(3):143–4.

-

Rowley J. Designing and using research questionnaires. Manage Res Rev. 2014;37(3):308–30.

-

Bowling A. Mode of questionnaire administration can have serious effects on data quality. J Public Health. 2005;27(3):281–91.

-

Vilagut G. Test-Retest Reliability. In: Michalos AC, editor. Encyclopedia of Quality of Life and Well-Being Research [Internet]. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands; 2014 [cited 2023 Oct 6]. pp. 6622–5. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-0753-5_3001

-

Abma IL, Rovers M, van der Wees PJ. Appraising convergent validity of patient-reported outcome measures in systematic reviews: constructing hypotheses and interpreting outcomes. BMC Res Notes. 2016;9(1):226.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the lands on which this study was conducted as the island of Ktaqmkuk [uk-dah-hum-gook] (Newfoundland) as the unceded, traditional territory of the Beothuk [bee-oth-uck], and the Mi’kmaq [mee-gum-maq] people. This study was part of the first author’s doctoral dissertation (QJ) at Memorial University of Newfoundland. We thank all the individuals who participated in completing the CHLQ. We would like to extend gratitude to the Stakeholder and Citizen Advisory panel members of the Cannabis Health Evaluation and Research Partnership (CHERP) team in Newfoundland & Labrador. A special thank you to Dalainey Drakes, Tanisha Wright-Brown and Michael Blackwood for their shared knowledge and discussions regarding the project. As well as all graduate students in the CHERP team for their unwavering support and assistance with this study.

Funding

The authors received financial support for conduct of the research from Canadian.

Institutes of Health Research(Grant No. RN407334–429120) and the Canadian.

Centre of Substance Use and Addiction for the Partnerships for Cannabis Policy (Grant.

No.RN407334–429120) inclusive of this research.

Author information

QJ, JD, LB, MN conceptualized the research idea and developed the methods. QJ, JD, LB, MN, RH developed, drafted and revised the questionnaire. JD led the data collection. QJ led and conducted the analyses, prepared, and wrote the initial draft of the manuscript. RH aided with data collection and revised the manuscript. JD, LB, MN, ZG reviewed the analysis and revised the manuscript. MN and JD supervised the study. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics declarations

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. All participants provided informed consent digitally via Qualtrics. Before accessing the questionnaire, participants were presented with a digital informed consent form and asked to select ‘Yes’ or ‘No’ to participating in the study. Only participants consenting ‘Yes’ were included in this study. Ethical approval for this research was obtained from the Interdisciplinary Committee on Ethics in Human Research (ICEHR) at Memorial University of Newfoundland. This study is a subproject of a larger research initiative and, as such, received two ethics approvals (20230628-PH; 20230882-ME).

Not applicable.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Search

RECENT PRESS RELEASES

Related Post