Environment: Adopt a tapeworm. Love your lice. Give a leech lunch

April 12, 2025

Parasites need our help, not our disgust. Electricity usage increases with the temperature, but the price falls as renewables increase. Cyanobacteria’s sliding door moment.

Parasites need conserving just as much as their hosts

Earlier this month, I was removing some weeds on a

Bush Heritage property on the NSW south coast – an area of subtropical rainforest on the escarpment that forms the Great Dividing Range just there. My colleagues and I admired the birds nest ferns, the eastern yellow robin, the bridal veil stinkhorn fungus and the sassafras trees, but we were less enthusiastic about the leeches. Generally speaking, humans tend to screw up their noses at parasites (with the exception perhaps of mistletoe), regardless of whether we or other species are the non-consenting hosts.

But why should we be more concerned about the welfare, and possible extinction, of koalas, whales, Maugean skates and snow gums than we are about tapeworms, lice, leeches and candida? They are all part of Earth’s biodiversity; they have all co-evolved over millennia with other species; they all occupy niches in Earth’s complex systems of life; they are simply doing what comes naturally. Why should they be any less deserving of our concern than any other form of life on Earth? Why are we not worried that some of them will become extinct? Probably some already have.

A recent

paper takes up these issues and argues that we should be very concerned about the likelihood of many parasites disappearing. The role of parasites in host evolution and immune system functioning, which increase the chances of survival at the individual and population level, is overlooked. Parasites influence food system dynamics and contribute to the flow of energy and nutrients through ecosystems. The authors

liken parasites to ‘“ecological dark matter” – an unseen force vital for sustaining life on earth as we know it, supporting ecosystems that are more diverse, more resilient, and more productive.

But notwithstanding their practical usefulness to individuals, species and ecosystems, parasites have their own intrinsic value (regardless of what humans think of them). As the authors say, “parasites should be recognised as equally valid targets of conservation as their host organisms”.

Parasites are threatened by the same factors that threaten other species: climate change, pollution, habitat loss, etc. In addition, they go extinct if their host goes extinct (co-extinction), often before the host finally disappears, because many parasites rely on a high density of their host species for their transmission. Australian parasites are at particular risk. Because we have so many threatened mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians, fish, insects and other invertebrates, we also have many threatened parasites in many ecosystems. To cap it all, when parasites are considered harmful to humans or other species that are important to us they are often targeted for eradication. Despite all that, only one animal parasite (the delightfully named pygmy hog-sucking louse) is on the

IUCN Red List of Threatened Species.

The authors lament the currently low levels of interest and activity in parasite conservation and identify a range of factors, including poor knowledge and appreciation of parasites and their roles; disgust with parasites’ appearance, lifecycles and effects on hosts; a bias towards hosts rather than parasites; and practical problems such as technical challenges, costs and biosecurity regulations. They advocate an interdisciplinary approach to research that includes social scientists developing a better understanding of sociocultural barriers to parasite conservation, environmental values and ethics and the philosophy of parasite conservation.

The paper argues: (1) for a more nuanced philosophical approach to parasite conservation that clearly identifies and applies the values being advanced; (2) that single-species conservation should move toward holobiont (the host and its entire biome) and holistic (the host and parasite in their evolutionary and ecological context) conservation;, and (3) an emphasis on parasite conservation practice not just research. (I love the idea of establishing parasite refugia to protect parasites, while efforts are being made to protect their threatened host species.)

This is, perhaps, the most interesting scientific article I’ve read in recent years, integrating considerations of evolution, complex ecosystems, human sociocultural issues (particularly values and prejudices), environmental ethics and philosophy, and conservation practice. It also introduced me to quite a few new words and concepts.

I can’t help wondering if parasitism really exists. Perhaps, if we knew more, we’d realise that so-called parasites are actually in a symbiotic relationship with their host and their ecosystem. From an evolutionary and systems perspective, one-way exploitative relationships seem rather unlikely.

Indian electricity consumption increases as daily temperatures rise

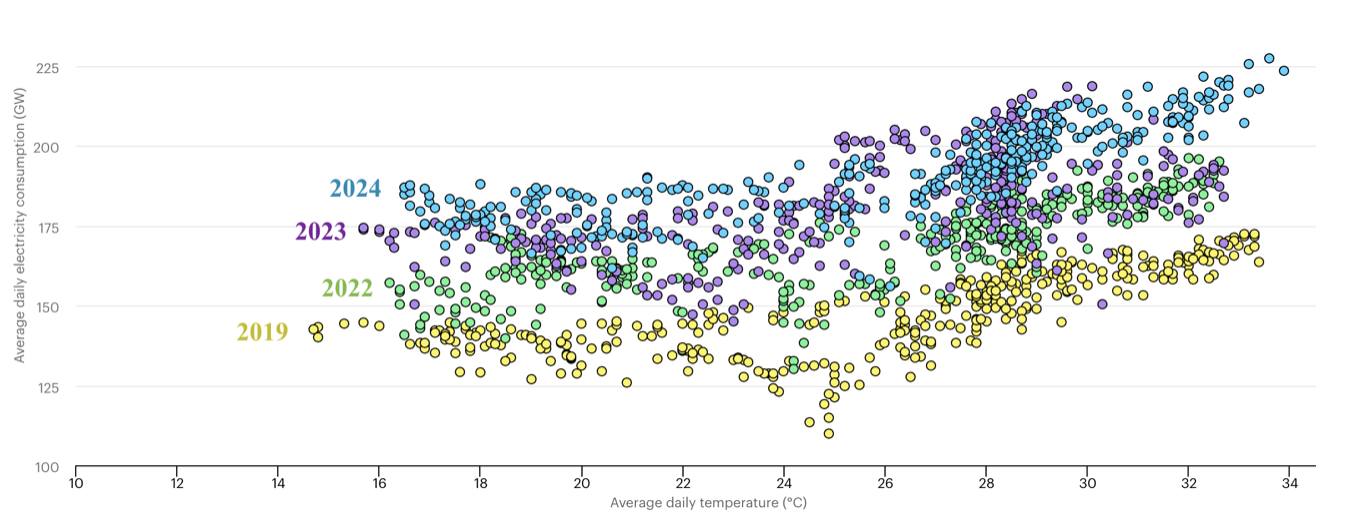

The graph below shows daily electricity use at different average daily temperatures in

India. Within each year, daily consumption remains fairly stable between about 14oC and 25oC, but at higher temperatures consumption increases – no surprise there.

What is more interesting is that at any particular average daily temperature, the daily consumption of electricity is increasing year by year. In fact, the average daily usage at the lower end of the temperature range (14-20oC) in 2023 and 2024 was higher than usage at the upper end of the temperature range (30-34oC) in 2019. This is indicative of both a greater propensity to use air conditioning and more families and businesses having air conditioning. It’s a remarkable change in just five years and India is still at the beginning of its economic development.

India is just one example of a much wider trend in developing and developed countries. Globally, electricity demand increased by more than 2% in 2024, almost twice the average of the last decade.

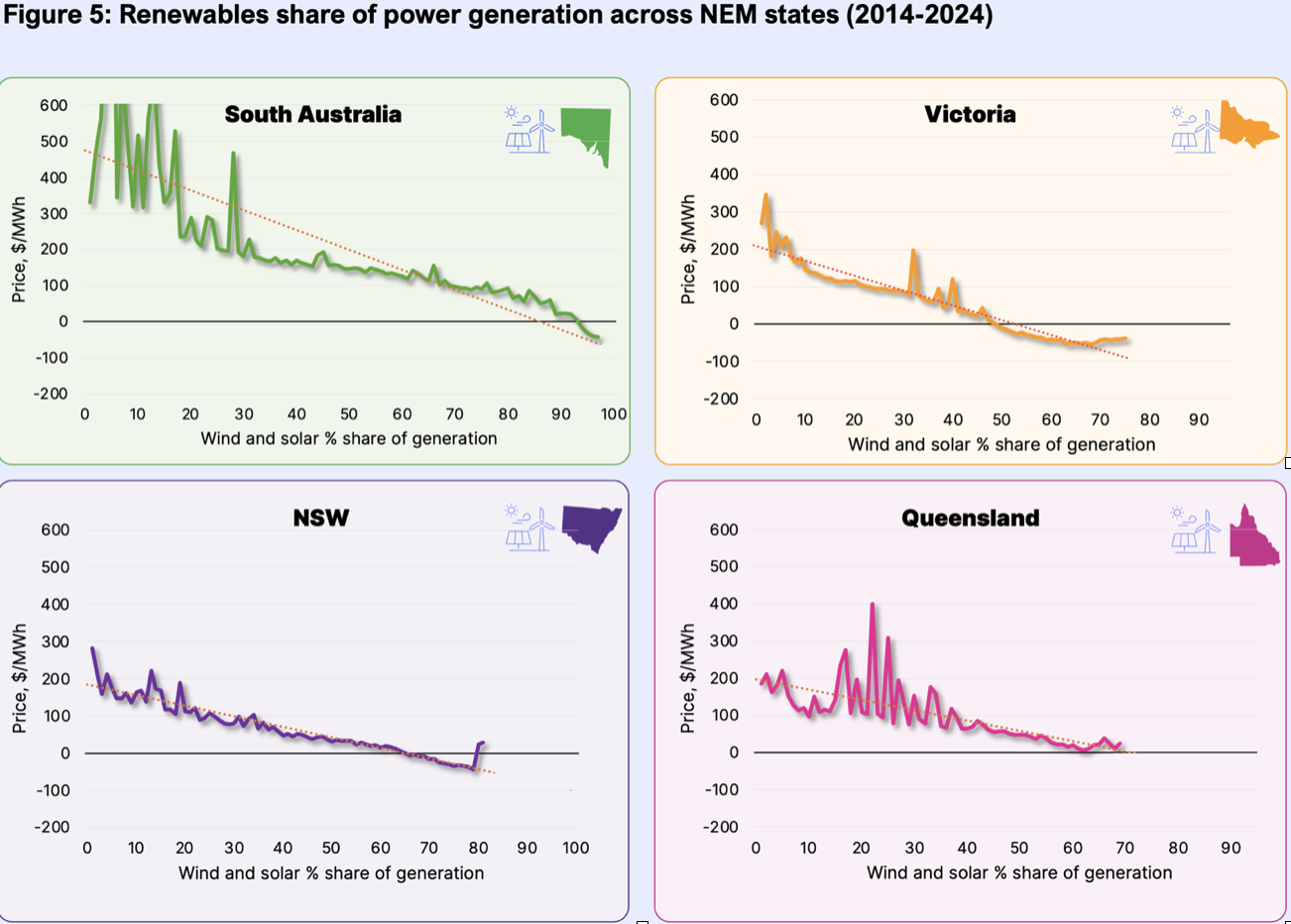

Australian electricity gets cheaper as renewables increase

The graphs below demonstrate that across the four mainland states of eastern Australia the wholesale spot price of electricity has fallen and become less volatile as the percentage of wind and solar in the electricity generation mix has increased.

The

wholesale spot price is the price that the 30 or so energy retailers pay the more than 100 energy generators for the immediate delivery of electricity before they sell it on to consumers. The price fluctuates every few minutes according to current (no pun intended) supply and demand – e.g. the spot price rises during a heatwave or if a coal-fired power station has a breakdown. Lower spot prices help to reduce the overall or average price that consumers pay their retailer for their electricity, but the cost of generating electricity makes up only 30%-40% of a household bill. Network costs (the poles and wires that transport the electricity) make up 40%-50%.

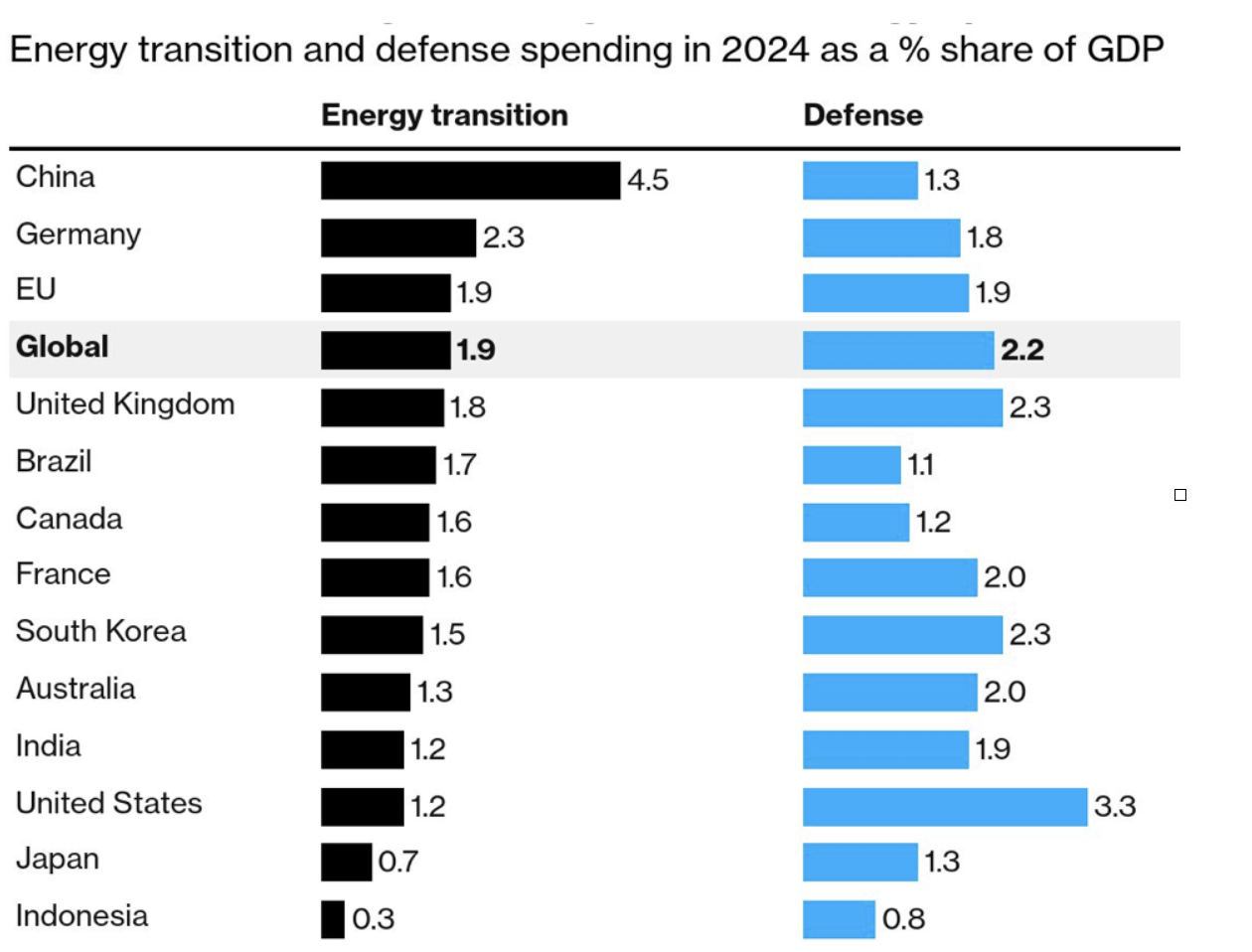

Defence 2.2 – Energy Transition 1.9

That’s the result of the penalty shootout for the Spending Priorities World Cup.

The table above, from Bloomberg Green Daily on 1 April, compares the percentage of global and selected countries’ GDP directed to defence and the energy transition. While I would prefer to see the global ratio reversed, to be honest, I’m pleasantly surprised that the two figures are so close.

More striking, perhaps, is the comparison of the US and China. The US spends almost three times as much on defence as the energy transition, whereas China spends more than three times as much on the energy transition. Interesting that Germany, Brazil and Canada also spend more on the energy transition.

It makes sense to me to spend more on changing our behaviours to accommodate the unbeatable laws of physics than on preparing to attack others and defend ourselves because we’re too selfish, greedy and stupid to live together peaceably.

2500bya cyanobacteria caused life’s sliding door moment

I suspect that if you asked 100 people what they know about cyanobacteria, the order of frequency of the (at least vaguely correct) answers would be: 1. Nothing. 2. Are they the same as blue-green algae? 3. They cause algal blooms in rivers and lakes. 4. Aren’t they something to do with those stromatolite things in Western Australia? 5. They were the first organisms to produce oxygen by photosynthesis. 6. If it hadn’t been for their ancestors producing oxygen two or three billion years ago (bya), we wouldn’t have any oxygen in the atmosphere today and complex life as we know it would not have developed.

I confess that although I did know about point 6, the details of it have always escaped me. ‘

The single-celled organism that almost wiped out life on Earth is a four-minute video that clearly, but briefly, explains how a mutation in a single-celled, anaerobic, ocean-dwelling organism dramatically changed the composition of the atmosphere and created the Great Oxygenation Event that wiped out nearly all life on Earth, but only “nearly”… the rest, as they say, is history.

Tongue-eating louse

Parasite: ‘any organism that is dependent on living on or in a host organism for all or part of their life cycle and that derives resources at the expense of the host, with the potential to decrease host fitness’.

I may have extolled the virtues of parasites, but I am glad that I haven’t encountered this little critter. The

tongue-eating louse parasitises small fish in the waters off Central and northern South America. The parasite makes the fish’s tongue fall off and then replaces the tongue with its own body. Did I mention that there’s also an Australian species? Better keep your mouth shut in the sea.

Search

RECENT PRESS RELEASES

Related Post