Exploring and expanding skills development across the built environment

January 15, 2026

Research

January 15, 2026

Executive summary

Millions of workers construct, operate, and maintain the nation’s built environment systems and facilities, from roads to pipes to power plants and beyond. Simply keeping up with needed expansions and repairs is a tall task, and today, new technologies and climate impacts are heightening demands, including the need to train and hire a deep bench of talent. Research around defining, measuring, and addressing all these jobs has been widespread in recent years, giving policymakers and practitioners an opportunity to equip more workers with the needed education and training to pursue careers across the built environment. Doing so can lead to better outcomes for workers, employers, and the economy as a whole.

This report investigates this opportunity to expand skills development across a variety of built environment careers—those focused on constructing, operating, and maintaining transportation, energy, water, broadband, buildings, and other related assets. Specifically, the report explores ways in which leaders can overcome the fragmentation—by infrastructure sector, geography, and more— of occupations and industries in this space through a skills-first approach, or one that helps identify and elevate skills-first hiring and training. In addition to offering additional context on this opportunity, the report summarizes key takeaways from a series of interviews Brookings conducted with employers, training providers, community-based organizations, labor groups, and other workforce development leaders on how to promote skills development with greater flexibility and coordination, especially at the state and local level. It describes how:

Larger national policy and funding uncertainties around the built environment and workforce development at the moment have obscured the actions that leaders can take on these issues. But many workforce development leaders across the country continue to blaze a path forward, revealing collaborative and replicable models around skills development in the built environment space.

Introduction

The country’s built environment faces pressures on multiple fronts. From aging roads to leaking water pipes to surging energy demands, many infrastructure systems are in desperate need of repair and investment. Daily wear and tear is one factor, but extreme and more frequent climate impacts are compounding these needs; floods, fires, freezes, and more are disrupting or destroying systems across the country. Ongoing concerns around greenhouse gas emissions and overall sustainability are mounting too, including across buildings, manufacturing facilities, and a broad collection of other facilities.

Meanwhile, the country’s workforce also faces widespread needs. Layoffs, hiring freezes, and other uncertainties are gripping the labor market amid broader economic concerns. Many workers cannot flexibly and affordably gain needed skills and training to secure jobs, let alone launch or grow in long-term careers. Both less experienced and more experienced workers are running into these hurdles, with a continued need to earn higher wages, gain more benefits, and secure quality jobs and job pathways. Employers, to be sure, are actively looking to find and grow talent as well. And rapid change—not just technologically, but also in terms of climate needs—continues to uproot many workers, employers, and other leaders trying to seize greater economic opportunity.

Together, these dual infrastructure and workforce needs are significant, but they also present an opportunity: equipping workers with durable and transferable skills to address the country’s built environment needs while powering long-lasting, opportunity-rich career pathways.

Previous Brookings research on the infrastructure workforce has explored the multiple branching pathways available in this space, in addition to the more competitive and equitable wages across a vast array of infrastructure industries. Since so many of these positions are in the skilled trades—such as electricians and plumbers, among others—they also tend to require less formal postsecondary education and emphasize work-based learning opportunities such as internships and apprenticeships. Moreover, with a rising number of retirements and other turnover concerns, there is an urgent need to hire, train, and retain a generation of talent.

However, despite this infrastructure opportunity, policymakers and practitioners—including workforce development leaders—face stiff headwinds to actually unlock it. Long-standing gaps in defining, measuring, and communicating this opportunity remain prevalent. Inflexible and traditional hiring and training practices, including an emphasis on certain degrees or other credentials, can prevent new talent from entering these jobs. And despite the passage of historic federal funding in recent years, including the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA) and Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), many state and local leaders have not always implemented (or rethought how to use) this money to support workforce development. Meanwhile, the current federal policy environment has led to huge ongoing questions for capacity-constrained state and local leaders.

This report aims to identify, contextualize, and address the need for ongoing skills development across the built environment amid the current policy backdrop. It focuses on a skills-first approach to a broad variety of careers in this space, expanding beyond prevailing analyses and efforts around “green jobs.” Rather than defining or analyzing a specific set of jobs in isolation, the report explores local policy and programmatic levers that can strengthen hiring and training pathways for more workers in more places.

The report first examines why skills development across the built environment matters. It then discusses the types of skills and credentials (e.g., educational degrees, licenses, certifications) needed, as well as the different actors involved. Based on a series of interviews with state and local workforce development leaders, the report concludes by offering ways to support skills development over time and demonstrating the strong economic benefit for workers and employers across the U.S.

Why skills development matters across the built environment

Equipping workers with the essential education and training to address the country’s built environment needs is no easy task. The wide variety of humanmade and natural infrastructure systems in need of oversight—from transportation and energy facilities to rivers, forests, and other related green infrastructure assets—means that there are an enormous range of activities involved and workers required. Constructing, operating, maintaining, and governing these systems depend on laborers, technicians, electricians, and other trades workers, for instance, as well as financial analysts, human resources specialists, and other administrative and managerial workers. There is no single job or skillset that stands out in this space.

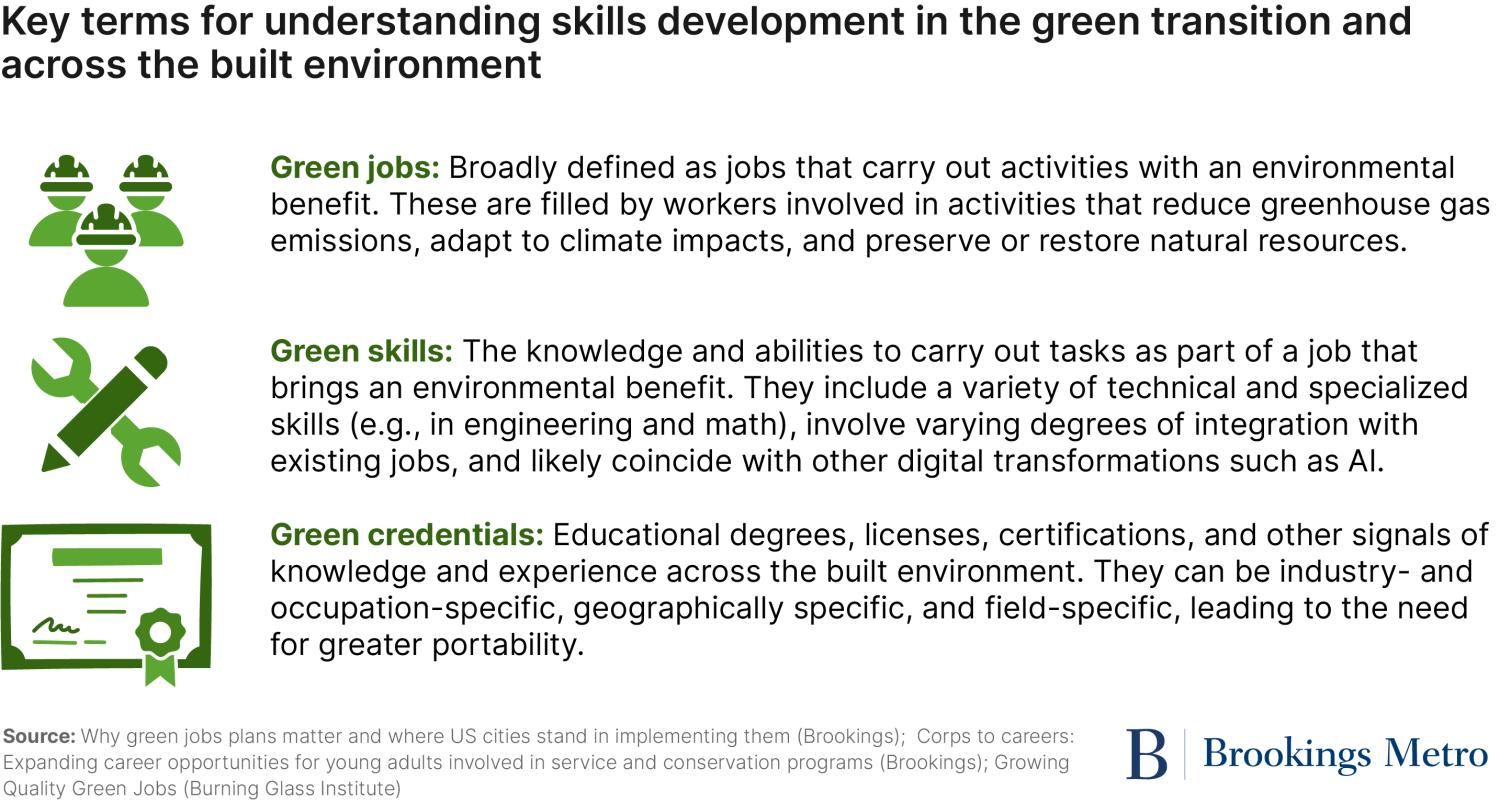

Increasing climate impacts and the transition to a cleaner and more resilient economy—or a “green economy”—have come to dominate much of the skills conversation across the built environment. Upgrading homes, installing electric vehicle charging stations, and improving transmission lines are among the various projects that workers may carry out. In turn, the real-time and projected importance of “green jobs”—broadly defined as jobs that carry out activities with an environmental benefit—has attracted interest and investment among policymakers and practitioners, including federal leaders, state and local governments, and other public and private actors (e.g., financial firms).

However, the broad scope of workers involved in activities that reduce greenhouse gas emissions, adapt to climate impacts, and preserve or restore natural resources leads to inconsistent definitions, measurement challenges, and practical limitations on managing and prioritizing certain workforce development efforts. For instance, researchers have often emphasized clean energy workforce needs, including past Brookings research, Bureau of Labor Statistics surveys, and the Department of Energy’s annual Energy and Employment Report, which estimates there are more than 8 million energy jobs nationally, including 2.3 million in energy efficiency alone. But shifts to clean energy only capture a share of all the built environment assets, activities, and workers in transition.

Seizing a broader built environment opportunity means looking beyond narrow or inconsistent categories of green jobs. The problem with classifying and counting green jobs is that outside of a few occupations (e.g., solar installers, wind turbine technicians), few workers fit clearly into a “green” or “non-green” category. As technologies, designs, and the nature of work keep changing across the country’s built environment, there is a wide spectrum of jobs impacted by the green transition. For example, while not all HVAC technicians may focus on installing energy-efficient heat pumps and other green activities, some increasingly do so; the same could be said for electricians involved in installing wiring for solar panels, auto workers manufacturing electric vehicles, and so on. The evolving nature of jobs—not just the appearance or disappearance of jobs—reflects the reality that workers, employers, training providers, and other leaders must navigate in real time, and over time.

That is why more researchers, policymakers, and practitioners are emphasizing skills across the built environment, including “green skills” —the knowledge and abilities to carry out tasks as part of a job that brings an environmental benefit. Similar to green jobs, no singular definition exists for green skills, although a growing body of literature and policy guidance has come out from international organizations such as the United Nations and World Bank, federal agencies such as the Department of Labor, groups such as Burning Glass Institute and Jobs For the Future, and a variety of local-serving associations such as C40 and the Local Initiatives Support Corporation.

Among these and many other institutions, a few consistent points around green skills stand out. First, green skills include a variety of technical and specialized skills—including science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM) fields, for instance—but also a variety of soft skills, including communication and management. Second, they involve varying degrees of integration, with some jobs adding them to existing knowledge and abilities and other jobs potentially changing more significantly over time. Lastly, they likely coincide with other digital transformations, including around artificial intelligence, data analytics, and other functions.

The uncertainties around what exact skills will become more prevalent—including when, where, and for whom—mean that related education and training efforts need to be adaptable in this changing environment too. Different projections and surveys are attempting to estimate the pace, location, and penetration of new types of skills across the labor market, but many workers, employers, training providers, and other actors are simply responding in real time to the best of their abilities. Educational institutions may adopt new curricula, employers may adopt new on-the-job trainings, and local governments may draft new workforce plans—but they do not always do so in close coordination. Ensuring there is an economically and socially equitable transition remains an ongoing exercise in many places, and the lack of proactive and intentional policies and programs may cap potential economic opportunities.

While workforce development leaders do not have a crystal ball to perfectly predict what jobs or skills will be needed over time, they can prepare a larger talent pool for a variety of roles across the built environment, ideally equipping them with flexible and interchangeable knowledge, abilities, and experience. That includes a focus on equipping workers with relevant “green credentials,” which span educational degrees, licenses, certifications, and other signals of knowledge and experience across the built environment. But it’s not about the paper or credential itself. Skills-first hiring (or skill-based hiring)—recruiting workers based on their skills and competences, not just their educational degree—is becoming increasingly important to reduce barriers for workers and employers alike. Ensuring workers have greater portability in the education and training they receive is critical amid the rapid, widespread changes unfolding across the built environment and labor market.

Expanding skills development and identifying the actors involved

Expanding skills development across the built environment involves promoting transferable and portable sets of skills and credentials.

On the skills front, built environment workers rely on a combination of technical and other foundational knowledge that includes familiarity and experience with plumbing, electrical work, and operating heavy machinery, for instance, but also communications, public safety, and security. As past Brookings research has explored, a wide range of occupations such as civil engineers, electricians, and pile-driver operators emphasize these types of skills—not just solar installers, wind turbine technicians, or other green-focused workers. STEM skills, again, are crucial for many of these workers, including those in the trades who tend to gain greater knowledge and competency with certain engineering concepts, mathematical principles, and tools and technologies (e.g., geographic information systems, computer-aided design software) through on-the-job training.

Credentials—green or otherwise—can serve as enablers (and barriers) to workers applying for jobs and growing their careers; they can be industry- and occupation-specific, geographically specific, and field-specific (in the case of STEM fields, for instance). Given the wide range of careers across the built environment, credentials vary from place to place and position to position; there is no centralized repository of all the potential education and training needed. Some credentials are widely recognized by employers, some take years and are very expensive for workers, and some take less time and are easier to access and benefit from. At the same time, the proliferation of non-degree credentials (e.g., specialized or short-term certificates) has led to an education and training marketplace that can be crowded and chaotic, with real questions about quality and whether employers recognize them.

Despite this fragmentation, some commonalities exist. Secondary and postsecondary education degrees (e.g., associate degrees, bachelor’s degrees) can involve coursework and curricula focused on architecture, design, engineering, and other content areas geared toward boosting built environment knowledge and familiarity. Examples are numerous, from community college programs in Oregon and Illinois on renewable energy management to undergraduate and graduate programs in Michigan and New York on sustainability and environmental policy. State-issued licenses for several climate-related occupations—from water treatment operators to environmental engineers—are also common and demonstrate a worker’s aptitude to pass an exam, gain needed work experience, and maintain their status. Professional, industry, and association certifications are frequently recognized across many positions as well, including building professionals with Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) certification, as well as broader positions such as certified construction managers (CCMs) and certified HVAC workers involved in air conditioning repair and installation. Completion of work-based learning opportunities, including registered apprenticeship programs, can signal valued competencies and experience to employers, such as the Building Trades’ Multi-Craft Core Curriculum (MC3) and the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers’ (IBEW) programs. Shorter-term, competency-based credentials—including online badges and other micro-credentials for individual classes, for instance—can also support continued learning and skills development.

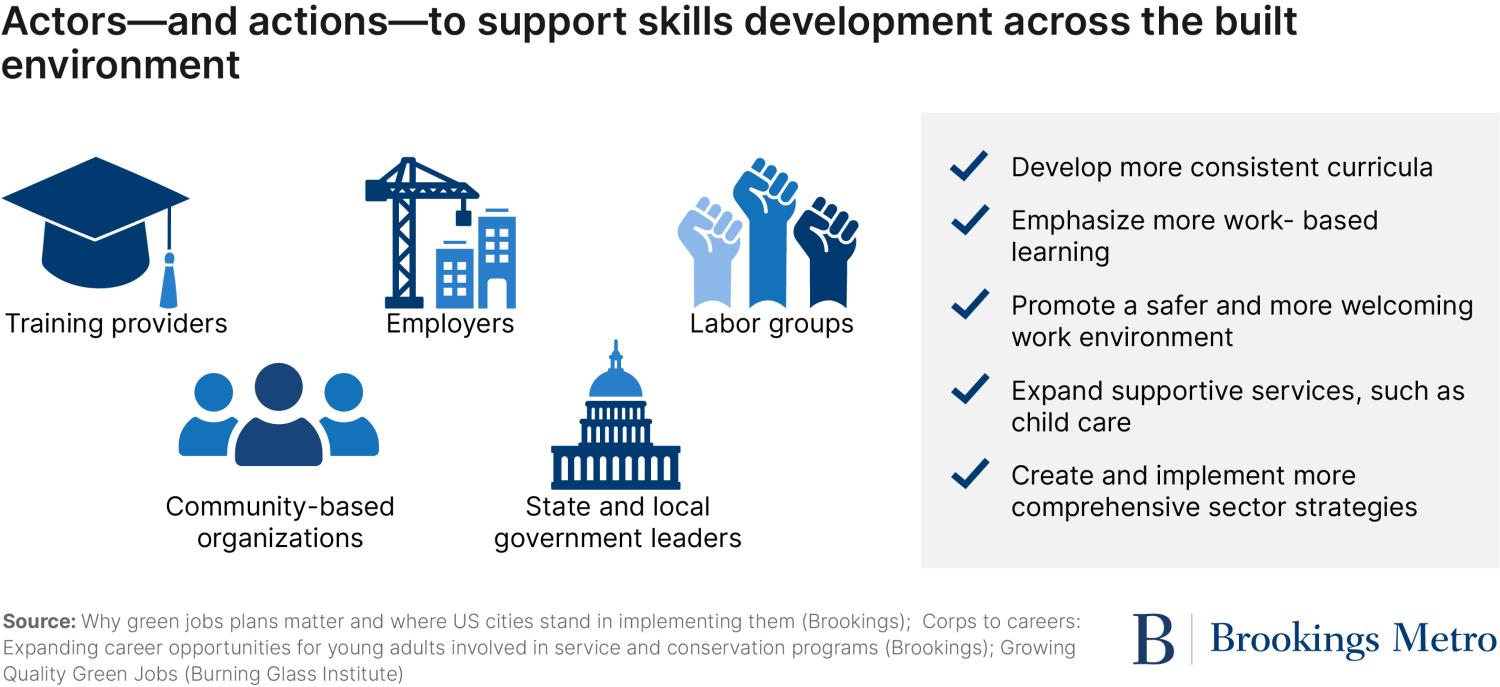

Beyond considering the specific skills gained and credentials earned, though, it’s perhaps even more important to examine and evaluate how a variety of workforce development leaders need to be involved. Expanding skills development will require more proactive planning and coordination across multiple occupations, industries, and geographies supporting the built environment, led by:

- Training providers, including secondary and postsecondary educational institutions, do not have consistent built environment or “green” curricula per se, and when they do offer related coursework, it can often be geared toward a specific occupation, field, or specialty in an individual region. This unique curriculum—versus a consistent curriculum—can limit the ability of students and prospective workers to earn and use flexible credentials as they ultimately move, change fields, and grow their careers. At a more practical level, a lack of qualified instructors, needed tools and equipment, and the cost and availability of some programs can also limit early exposure and education in the skilled trades.

- Employers, especially those across the built environment, typically operate in isolation, cling to business-as-usual hiring and training practices, and focus on project development versus workforce development. For instance, many transportation departments, water utilities, and engineering and construction contractors rely on prevailing HR processes (e.g., rigid degree requirements) and word-of-mouth to bring on new hires and compete against each other to secure scarce talent. They also do not have the bandwidth (financially or otherwise) to actively engage with communities, and may not always coordinate with other training providers—even though doing so could help them more reliably and cost-effectively prepare workers. These shortfalls can limit the potential for expanded on-the-job training, career growth, and other critical learning opportunities for workers—to say nothing of the benefits that these employers can gain from having a bigger, more dependable pipeline of talent for their projects over time.

- State and local government leaders, including workforce development boards, labor departments, and infrastructure-related agencies (e.g., housing and environmental agencies) face a variety of planning and programmatic needs to accelerate skills development across the built environment. Chief among them is a continued lack of technical, financial, and managerial capacity to expand (or even experiment with) new workforce development strategies—a constraint that is becoming more pronounced amid the pullback in federal workforce, climate, and infrastructure funding. State and local bodies, such as state energy offices, also remain chronically understaffed. But even in places that have more resources, there are still prevailing challenges around crafting comprehensive green workforce plans, implementing those plans, and measuring and evaluating outcomes as part of a larger, more cohesive workforce development ecosystem. In addition, it is crucial to note the role of state and local political leadership—as well as regulatory bodies—to address prevailing workforce development needs, requirements, and other priorities.

- Community-based organizations, typically including local-serving nonprofit groups that provide various forms of assistance and support, act as vital conduits to expose, prepare, and help workers pursue careers across the built environment. But these organizations also face many constraints. Lower-income, disadvantaged workers benefit from the supportive (and wraparound) services that these organizations can provide, including child care and transportation, but resource limitations remain a constant amid escalating demands. Reaching workers in need can be time- and resource-intensive, and measuring and assessing the outcomes of workers remain ongoing needs in data collection, analysis, and programmatic oversight.

- Labor groups, unions, and other worker advocacy organizations are crucial partners in educating and training workers across the built environment, in addition to advancing workers’ rights and improving workplace conditions. But these groups can encounter challenges diversifying their ranks and consistently promoting a more inclusive workplace, especially for women and people of color in some industries and occupations. Rethinking existing training approaches and worker representation is also an emerging concern as new technologies and the nature of work change rapidly across the country. Continued tensions—real or perceived—with some employers and among some workers also remain a challenge for these groups.

In this way, the point of expanding skills across the built environment is less about the single piece of paper (or digital badge) a worker may receive, and more about the flexible set of education and training pathways they can pursue and benefit from as they look to enter and grow their careers. Yet the fragmented set of workforce development actors across the built environment means there is no clear owner of all these pathways (and subsequent hiring processes and long-term career growth)—demanding more proactive planning and programmatic coordination.

Improving and coordinating skills development across the built environment

To get a better sense of how workforce development leaders can forge stronger, more coordinated education and training pathways, the Brookings team interviewed a cross-section of leaders involved in the built environment across the country. These interviews emphasized the perspectives of leaders at the state and local level—including training providers, employers, government agencies, community-based organizations, and labor groups—with the aim to gain actionable insights around: 1) a priority set of skills; and 2) a promising collection of education and training programs that can accelerate the development of these skills and may be potentially scalable across regions.

Not surprisingly, no single credential, skill, or programmatic solution emerged during these interviews, but they shed light on how and where promising education and training efforts have emerged, with an eye toward both real-time and longer-term workforce needs. Common ingredients in these efforts included a need to emphasize a broad suite of built environment priorities, improved coordination with employers (and industry more generally), and continued experimentation across different places and project types. Five key takeaways are summarized below:

Workforce development leaders need to think more comprehensively about ‘infrastructure skills,’ not just ‘green skills’

While many leaders recognized the urgency of climate impacts and the unknowns emerging in the green transition, they also voiced distrust and skepticism in the overemphasis on green jobs, green skills, and green credentials. The “green” tag associated with different education and training pathways can be polarizing at times, politically and otherwise. While some positions undeniably require specific types of climate-related knowledge and experience (e.g., solar installers), a “whole building” approach would likely make more sense for more workers, especially at the beginning of their careers—that is, having a broader emphasis on construction, engineering, and other fields commonly found across the built environment. To several leaders we interviewed, the green credentials that workers pursue are only “green” in as much as the specific projects they may ultimately oversee also happen to be green (e.g., clean energy upgrades).

Instead, acknowledging—and pursuing—a cross-sectoral approach (e.g., for transportation, energy, water, and so on) could allow for greater transferability in education and training across multiple built environment industries and occupations. Leaders noted how these could include cross-cutting “infrastructure skills,” which emphasize STEM-related knowledge and familiarity with certain tools and technologies, as noted earlier. Multiple career pathways are available to workers in this space, and leaders need to foster different tiers of skills—from basic employability skills needed to launch a career (as evident in YouthBuild and Job Corps programs, for instance) to more specialized skills and associated credentials over time. One occupational example that leaders cited for the latter is Environmental Protection Agency Section 608 certification, in which HVAC technicians can demonstrate their additional knowledge and experience as their careers evolve.

Notable place-based examples include the DC Infrastructure Academy and Austin Infrastructure Academy, which leaders said demonstrate the types of sector strategies and broader skills development needed across the built environment. Both examples integrate education and training opportunities at a regional scale by serving as a single destination where employers, educators, community-based organizations, and other actors can coordinate on community engagement, work-based learning, and more. These academies have linked together training with immediate and long-term hiring priorities, while also pooling available funding and providing supportive services.

Workforce development leaders need to blend credentialing with work experience and continued career growth

Leaders we interviewed described how credentials alone should matter less than ensuring workers demonstrate the necessary skills to do the job. Employers, in particular, stood out as a key actors in this respect, in which enhancing work-based learning opportunities should be a major priority given the emphasis on trades positions across the built environment. Apprenticeships and pre-apprenticeships were common examples, but leaders stressed how employers also need to more generally assume a more proactive role of “blending” credentialing with work experience and other factors. Process-wide improvements in the pre-hiring process were raised, including “customized, job-specific training services” evident in efforts such as the Virginia Talent Accelerator Program, among other state- and local-led initiatives. Beyond credentialing, leaders emphasized how training process changes are essential.

Several employers, of course, have already implemented such changes, offering precedent for broader, industry-wide adoption. Buy-in from leadership, amplifying a clear mission, willingness to consider changes in the hiring process, and investing in staff (especially around community engagement) were among the changes described, especially among contractors in the construction industry. The splintering of roles and responsibilities across the built environment, including for different projects in different geographies, means that contractors vary widely in their emphasis on (and capacity around) skills development—which is why having a clearer, industry-wide policy framework is essential to guide action. The Green Workforce Connect program represents a prominent example of how employers, community-based organizations, training providers, and other leaders have been able to create a common platform of collaboration. The availability of open source curricula and other employer best practices via the Center for Energy Workforce Development (CEWD) has also helped. Leaders noted how different carrots and sticks—such as project labor agreements and building code changes—have the potential to shift employer action, but they also noted how compliance-driven efforts can be off-putting and confusing for employers.

Skills development needs greater scalability across the built environment—and across different geographies

Leaders we interviewed repeatedly stressed numerous challenges in skills development given the fragmentation across the built environment. Transportation departments, water utilities, energy agencies, engineering and construction firms, and other employers do not usually plan projects together, develop coordinated budgets for training, or address other shared hiring needs over time as a larger, unified sector. Meanwhile, educational degrees and licenses can be highly localized—not only because of state-specific regulations, but also because of occupational nuances and particular employer demands. Data on training needs, hiring challenges, and worker outcomes can vary widely from place to place—or be missing entirely in certain built environment fields. Beyond formal credentials, skills-first hiring is an area of ongoing need for workers, employers, and other actors when it comes to validating skills, coordinating across different industries, and relying on legacy screening and hiring processes.

However, having greater scalability and portability to skills (not just credentials) can help overcome some of these challenges. For example, leaders pointed to the need for more industry-driven and standardized curricula in educational institutions, as accreditation bodies such as the Interstate Renewable Energy Council (IREC) have done for more than 200 clean energy training programs nationally. Creating more objective and reliable measures around skills-based hiring can also help by clarifying the benefits of this hiring model and creating clearer policy frameworks, which states such as Massachusetts and Washington have done. Standardized data dashboards on different climate projects and economic impacts can establish more quantifiable and outcome-driven measures, which organizations such as the American Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy (ACEEE) does through its state energy-efficiency scorecards.

Both upskilling and re-skilling are essential to meet current and future built environment demands

Supporting the short- and long-term mobility of workers across the built environment requires meeting workers where they are currently and want to be ultimately—not just leveraging their skills or credentials for a particular position or project. Doing so can also more assuredly help employers—including many infrastructure owners and operators—address ongoing maintenance and capital needs. That means developing a workforce, not just leveraging it, as leaders described in the interviews. Incentivizing employers (financially) to prioritize ongoing workforce development is one possible path to do so—as attempted in the rollout of IIJA and IRA funding—but these efforts need to extend well beyond this policy window.

In particular, leaders emphasized a combination of upskilling and re-skilling for less experienced and more experienced workers alike, including providing necessary supportive services for continued learning and transitions. Engaging with students and disconnected youth requires greater (and more frequent) visibility and exposure to skilled trades careers in particular, via pre-apprenticeships, apprenticeships, and other service- and workforce-based learning opportunities. For example, training resources from the Center for Energy Workforce Development (CEWD) has helped boost employer engagement on these issues, as has coaching and technical assistance efforts from organizations such as UnidosUS. Similarly, it is important to reach workers further in their careers who might be unemployed, underemployed, or simply looking to move into a different field. Organizations such as JobsFirstNYC, for instance, have spearheaded regional collaborations around green workforce development, aimed at expanding access for different workers and cultivating longer-term pathways for career growth.

Experimentation with place-based and project-based opportunities is essential to drive longer-term change

Adjusting how workers, employers, and other actors view credentials—and their approach to training—is a tall task across multiple industries and geographies. However, leaders described the importance of more frequent experimentation—grounded in particular places and projects—to build greater momentum and offer a clearer demonstration of how skills development could occur more seamlessly across the built environment. There needs to be an intentional focus on skills development, not just a coincidental focus. They described the co-determination that needs to occur between policymakers and practitioners at the state and local level to better gauge labor supply and demand, encourage engagement among employers and training providers, and integrate learning with project development and execution.

Examples abound across the country on how such intentional and proactive approaches have emerged in this space. At the state level, for instance, the Texas Climate Jobs Project represents a coalition of unions launched in 2021, and has partnered with different actors in different places to intentionally center worker access and training, from building decarbonization to larger energy projects focused on methane reduction. Policymakers in Maine have also launched ambitious, targeted efforts around efficient heat pump installation, combined with active engagement with the state’s community college system to train hundreds of new technicians. At a more local level, infrastructure investments from the IIJA and IRA coupled with technological shifts toward AI have also propelled new collaborations: an urban forestry accelerator in Phoenix, advanced manufacturing training centers in Reno, Nev., weatherization development programs in Minneapolis, and green infrastructure training efforts in Atlanta. The wide variety of examples emerging nationally shows the continued appetite to test new ideas and approaches, even amid other policy and economic uncertainties.

Despite funding and policy shifts, there remains a need for skilled talent across the built environment

Whether filling jobs or boosting skills, the demand for talent across the built environment is clear. Employers, training providers, and other leaders continue to voice their need for a durable and dependable pipeline of talent to address project needs across a host of different systems and facilities. The magnitude of this need—including the wide range of activities being carried out, the skills required, and the geographies represented—means that larger, system-wide approaches are essential to drive change. Fluctuations in funding and other policy shifts—especially around greener upgrades—have called into question some prevailing projects and workforce development efforts, but they have not fundamentally altered the underlying calculus: The country’s built environment requires a steady stream of skilled workers to predictably and reliably execute on needed improvements.

Fortunately, several models (and examples) have emerged in recent years, highlighting actionable steps that many state and local leaders have been able to pursue. Collaborative and scalable programs centered around work-based learning have taken hold; more flexible and accessible credentialing opportunities have appeared; and more consistent and outcomes-oriented data around skills development have helped guide action. These and other efforts continue to build the case—and demonstrate proof—of how careers across the built environment offer pathways to greater economic opportunity over time, cultivated by intentional planning, programmatic coordination, and ongoing experimentation.

-

Acknowledgements and disclosures

Brookings Metro would like to thank Indeed for their generous support of this report. The views expressed in this report are solely those of its author and do not represent the views of the Brookings Institution and its donors, their officers, or employees.

The author would also like to thank the multiple organizations and individuals who helped inform the national, state, and local opportunities to expand skills development across the built environment. The author would like to especially thank Martha Ross for offering guidance and substantive input on earlier drafts, as well as Ben Schribman for excellent research assistance.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Search

RECENT PRESS RELEASES

TDF Investing Linked to Upticks in Retirement Confidence

SWI Editorial Staff2026-02-05T08:59:18-08:00February 5, 2026|

Ethereum treasury ETHZilla (ETHZ) pushes deeper into tokenization with $4.7 million in hom

SWI Editorial Staff2026-02-05T08:58:30-08:00February 5, 2026|

Ethereum’s Vitalik Buterin Says No More Copy-Paste EVM Projects Needed

SWI Editorial Staff2026-02-05T08:57:59-08:00February 5, 2026|

Ethereum Falls 10% In Bearish Trade By Investing.com

SWI Editorial Staff2026-02-05T08:57:36-08:00February 5, 2026|

Here’s What Needs to Happen for Ethereum to Hit $5,000 This Year

SWI Editorial Staff2026-02-05T08:57:06-08:00February 5, 2026|

Leading sports investment firm Arctos acquired by private equity giant KKR

SWI Editorial Staff2026-02-05T08:02:18-08:00February 5, 2026|

Related Post