Five Recommendations to Diversify and Accelerate Investments in Nature-based Solutions for

June 16, 2025

Mónica A. Altamirano de Jong, Brooke Atwell, Michael T Bennett, Leah Bremer, Alain Du Cap, Gena Gammie, Todd Gartner, Colin Herron, George Kelly, Jim Lochhead, John H. Matthews, Alexis Morgan, Naabia Ofosu-Amaah, James Salzman, Daniel Shemie, Mia Smith, Sophie Tremolet, Paola Zavala, James Dalton, and Gregg Brill

These recommendations were originally published in Doubling Down on Nature: The State of Investment in Nature-based Solutions for Water Security, 2025. They were developed and endorsed by a group of experts and practitioners, acting in their individual capacities.

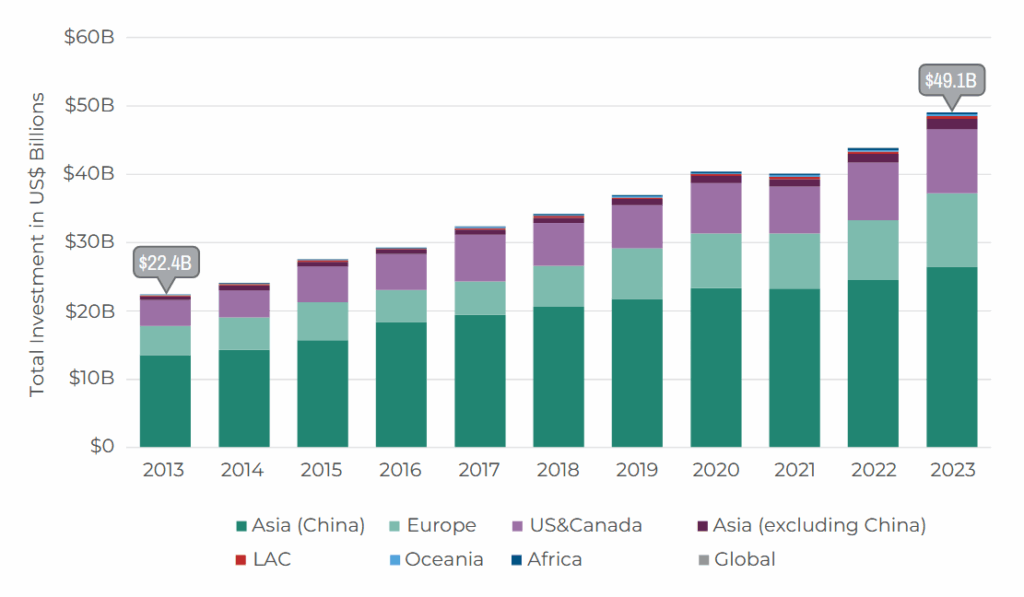

Nature-based solutions (NbS) are no longer a fringe concept. They are becoming an essential tool to address water security in the face of climate change, growing demand, and ecosystem degradation. NbS driven by water goals now represent one of the most resilient sources of financing for nature (UNEP 2023). The State of Investment in Nature-based Solutions for Water Security report shows that investment in NbS for water security has more than doubled over the past decade—even through disruptions like the COVID-19 pandemic.

Beyond water security, NbS advance national and global goals on biodiversity, disaster risk reduction, and climate change—critical areas facing persistent financing gaps. For instance, the COP29 UN Climate Change Conference called for scaling climate finance to USD 1.3 trillion annually by 2035, and the Global Biodiversity Framework set a target of at least USD 200B per year. The report shows that water-driven NbS investment reached USD 49B in 2023, demonstrating its potential as a scalable pathway to help close these gaps.

Yet the field remains fragmented and faces persistent challenges. Drawing on the first global assessment of investment in NbS for water in a decade and our own experience, we observe the following set of challenges to continuing to scale effective, sustainable investment in NbS for water security:

- Nature-based solutions are not fully integrated into gray infrastructure planning or as part of hybrid approaches, resulting in missed opportunities to increase resilience, co-benefits, and cost-effectiveness.

- Financial gaps remain, particularly for long-term funding for operational expenditures (OPEX) needed to sustain and monitor NbS benefits over time—a challenge that affects all infrastructure but is often especially acute for NbS given limited precedent and dedicated funding streams.

- In places where demand for NbS has grown, implementation capacity often lags behind, with shortages in the workforce (from skilled project developers and procurement officers to local labor) and restoration equipment slowing project delivery.

- Funding from national governments continues to dominate, but outside of China, continued growth—or even maintenance—of NbS investments is uncertain, as investments may become politicized and public resources are redirected to address national security concerns and economic turbulence.

- Private sector engagement and funding is inhibited by high perceived risks, lack of awareness, and insufficient regulatory drivers. Additionally, preference for unilateral investments in NbS by businesses has led to fragmented, siloed projects rather than effective collective action.

- Transaction costs remain high for these investments and difficult to cover, despite being essential to making NbS investable. These costs—including early investments in business case preparation, project design, capacity development, collective action mechanism setup, and rigorous result evaluation—are often excluded from direct investment figures; if nature were fully integrated into infrastructure planning and finance, such costs would be systematically priced into the system.

- Current delivery models of NbS often fall short in enabling Indigenous and local communities to participate in and lead NbS design and implementation, limiting the integration of traditional knowledge and raising concerns about community buy-in, ownership, and long-term success.

- Data on the water-related benefits and cost-effectiveness of NbS investments are not systematically collected or made publicly available. Rigorous ex-post evaluations remain rare, due to insufficient data collection practices and difficulties establishing baselines and counterfactuals. This makes it hard to assess outcomes, attribute impacts, and improve future planning and business cases.

- Data on investments by the private sector and other water users, like utilities, are also often not publicly available or easily accessed, limiting visibility into the scale, nature, and potential of these emerging sources of finance.

Five Key Recommendations

Considering these challenges, we offer five key recommendations to diversify and accelerate NbS investments:

1. Build Reliable and Resilient Revenue Models

Predictable, long-term funding is essential—particularly given rising risks to centralized public funding for NbS. While the scale of national funding will not be replaced by other payers in the short term, models that draw on direct beneficiaries of NbS, such as water users or property owners, show the greatest promise for durability and growth.

- Mainstream Revenue Models based on User Fees: The report highlights effective, long-term funding models supported by water users, including user fees consolidated in public agencies, like South Korea’s watershed funds, France’s water agencies, and Brazil’s watershed committees, and tariff-based mechanisms managed by utilities, as in Peru, the UK, and the US. Successful models are typically incorporated into tariff structures and are obligatory contributions by water users within a given jurisdiction or utility service area. Recent public opinion surveys suggest such measures may garner strong public support, especially if framed as protecting and restoring freshwater and natural resources. Ministries and regulators should strengthen and replicate these models to ensure that NbS have a reliable, long-term source of funding, just like built infrastructure needs, for both capital investments, maintenance, and monitoring.

- Leverage Co-benefits to Diversify Funding Pool: NbS generate value beyond water—including carbon sequestration, livelihood benefits, biodiversity protection, climate resilience, and property value gains. These co-benefits can be harnessed to unlock additional funding through mechanisms like other ecosystem service markets (e.g., based in the US, Virridy has developed a methodology for carbon credits projects that support NbS by accounting for avoided emissions from gray infrastructure that would have been needed without them), or through land value capture strategies, where increased property values linked to NbS generate public revenue, as in the Msimbisi Basin in Tanzania.

- Bridge Gaps in Low-resource Settings: In least developed countries, development assistance and philanthropy will remain essential in the near term to fund NbS, as opportunities for local revenue generation remain limited. With aid levels declining, support should focus on building the foundations—legal frameworks, capacity, and pilots—for future self-sustaining models.

2. Strengthen Policy and Planning for Long-term Impact

Upstream policies and planning frameworks shape the feasibility and quality of NbS investments. Integrated strategies are critical to embed NbS into national infrastructure, biodiversity, water, disaster risk reduction, and other related agendas, finding synergy across sectors and ecosystem services, and attracting new partnerships.

- Leverage National Commitments Under Global Policy Frameworks: Countries should clearly link both public and private investments in NbS to their plans for meeting national targets under global frameworks, including the Sustainable Development Goals, Nationally Determined Contributions and National Adaptation Plans under the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change, and National Biodiversity Strategies and Action Plans. The Freshwater Challenge can be a helpful platform for reporting progress across these frameworks. These plans should be articulated across sectors, to highlight national priorities and position countries that unlock climate, biodiversity, and development finance—serving as a kind of “shopping list” for potential partners. This approach can also help to identify opportunities for synergy at multiple levels.

One of the Xochimilco wetland channels that supply water for traditional agricultural systems under restoration with the Chinampa-Refugio model, Mexico City, Mexico. Photo credit: Victor Martinez. Submitted by: Conservation International - Integrate NbS into National and Subnational Infrastructure Planning: Governments should integrate NbS into national infrastructure and water resource management master planning processes, ensuring nature is included in long-term investment priorities. Lenders, including multilateral development banks, should offer policy loans to help government agencies build a pipeline of green or hybrid green-gray investments supported by enabling policies, including national commitments.

- Strengthen Regulatory Frameworks for Public Investment and Contracting for NbS: Policymakers and regulators should explicitly recognize NbS within infrastructure planning, investment, and procurement rules. Beyond removing barriers to NbS, these rules can leverage significant public funding for NbS to shape the future of the sector, including by promoting efficiency and private sector investment (e.g., through results-based procurement and public-private partnerships), facilitating greater participation by local and Indigenous communities, and requiring monitoring and reporting to promote transparency around NbS outcomes.

3. Grow and Steer Private Investment to Highest-Value Use

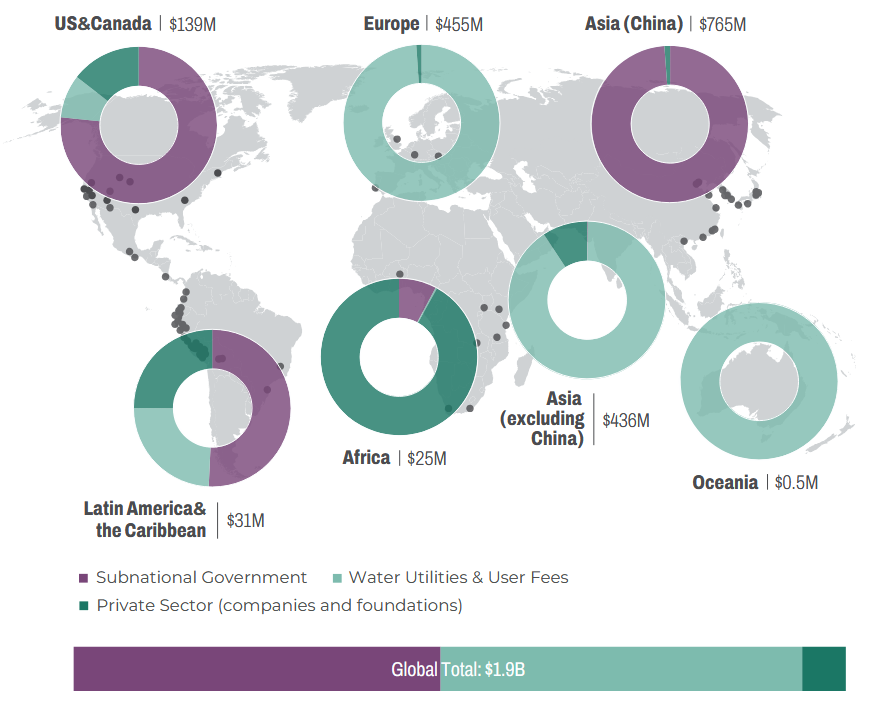

The private sector currently accounts for less than one percent of global investment in NbS for water security. While it won’t replace public funding, private investment can play a catalytic role when strategically aligned, and public partners can help shape the enabling environment to channel this investment toward scalable, high-impact solutions.

- Strengthen Policy and Regulatory Incentives: Where politically feasible, regulations are the most effective tool to expand private participation in NbS. This includes requiring contributions to publicly-run initiatives based on water use (e.g., Vietnam’s Forest Protection and Development Fund), creating frameworks that link compliance with ecosystem outcomes (e.g., state-led water quality trading programs in the US), requiring companies to disclose water and nature-related risks and mitigation measures, and offering tax breaks associated with NbS.

- Leverage Collective Action and Public-Private Delivery Models to Unlock Private Capital: In watersheds where multiple actors share common water risks, NbS proponents should explore a spectrum of public-private partnership models to secure private sector engagement, accelerate delivery of NbS, and generate greater impact. By using public or philanthropic funds to underwrite transaction costs associated with developing collective action and public-private partnerships, NbS proponents can incentivize private investments, which are often outcomes-focused. Coordinating around an anchor institution—often a utility, government agency, or major company that has a large, long-term stake in a specific watershed (e.g., Quito’s EPMAPS water utility or China’s Moutai liquor company in the Chishui watershed)—can help sustain funding and momentum long term. In cases where there is a large private sector anchor, the issuance of corporate bonds for NbS may be viable to provide up-front capital.

- Performance-based arrangements (like public procurement based on impervious acre reductions in the Chesapeake Bay in the US, or DC Water’s Environmental Impact Bond to finance urban green infrastructure for stormwater runoff) incentivize private investment by linking payment to verified environmental outcomes. Such models also tap into private sector delivery capacity and innovation.

4. Strengthen the NbS Delivery System and Evidence Base to Scale Impact

Scaling investment in NbS for water security requires not just more funding, but a stronger delivery ecosystem—grounded in skilled professionals, trusted data, and compelling evidence of impact.

- Strengthen the NbS Delivery Ecosystem: Whether in master planning, project preparation, or operations, there is a dearth of NbS professionals. To grow the field, urban planners, water managers, engineers, procurement officers, and local implementers should receive training in NbS design, contracting, and maintenance in sectors and geographies where demand is growing rapidly. Clear, region-specific technical standards for NbS—such as intervention specifications and survival benchmarks—can also streamline procurement and improve quality control, while building confidence among investors and creating predictable markets for private service providers. Standards should remain adaptable to local conditions and community knowledge.

- Strengthen Monitoring and Evidence through Collaboration and Technology: NbS implementers, beneficiaries, funders, and governments should work together to build robust, flexible monitoring, evaluation, and learning systems that ensure transparency and accountability across scales, while remaining relevant to local priorities. Harnessing technologies like remote sensing and artificial intelligence—alongside local knowledge—can lower costs, improve consistency, and scale performance monitoring of environmental, water, and livelihood outcomes.

- Make Outcomes Visible to Build Support and Drive Investment: Communicating tangible, local benefits, such as improved livelihoods, water quality, or flood protection, through robust data as well as community voices and grounded storytelling can build public and political will. Additionally, sharing data on investment flows and outcomes through publicly-accessible platforms can further improve transparency, foster learning, and highlight opportunities to scale NbS where it matters most.

5. Empower Local Knowledge and Leadership

Large-scale NbS programs often struggle to effectively engage local and Indigenous communities despite these groups holding deep knowledge of ecosystems and playing a critical role in sustaining long-term outcomes. Successful, durable NbS requires their leadership from the start.

- Strengthen Indigenous and Community Leadership in NbS: NbS initiatives should embed local and Indigenous leadership—including women, men, elders, and youth—in design, decision making, and implementation rather than exclusively as beneficiaries. This includes directly funding Indigenous and local communities, incorporating their knowledge and practices, and removing systemic barriers to their participation, including adapting procurement processes or facilitating partnerships that create accessible entry points, especially for women and youth. Canada’s Coast Funds offer a robust model for co-governance—through boards with First Nations representatives and grantmaking to Indigenous groups tied to Indigenous-led land use plans that incorporate ecosystem-based management.

- Prioritize Direct Benefits and Community Priorities in Program Design: Initiatives should ensure that local communities implementing and maintaining NbS receive equitable compensation and share in the benefits created by the effort. For example, successful programs, like New Zealand’s Jobs for Nature, have demonstrated how linking NbS to rural employment can generate these local benefits while building political support and ensuring delivery capacity. Likewise, equitable compensation and benefit-sharing should prioritize community needs, which may expand beyond water security to education, health, or cultural practices. The Upper-Tana Nairobi Water Fund Trust hosts youth track races for local communities, and Tribes participating in the Rio Grande Water Fund have invested in youth education and food security initiatives, like seed banks.

Conclusion

NbS for water security are gaining traction, but unlocking their full potential requires targeted action across finance, policy, delivery, monitoring and community engagement. The sector must replicate successful models while building the systems—workforce, standards, learning, and innovation—to expand effectively without losing flexibility. Sharing learnings from diverse approaches and incubating promising solutions to the challenges above can help the field deliver on its potential.

These recommendations offer a roadmap to move from scattered innovation to sustained, scaled investment—ensuring NbS can deliver scaled impact for people and nature.

These recommendations were developed and endorsed by a group of experts and practitioners, acting in our individual capacities:

- Mónica A. Altamirano de Jong, Founder, ALTAMIRA and partner NetworkNature EU

- Brooke Atwell, Associate Director, Resilient Watersheds, The Nature Conservancy

- Michael T Bennett, Conservation Finance Professional

- Leah Bremer, Associate Director, Institute for Sustainability and Resilience; Faculty, University of Hawaiʻi Economic Research Organization (UHERO) and Water Resources Research Center (WRRC), University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa

- Alain Du Cap, Senior Advisor, Environment and Climate Partnerships, Global Affairs Canada

- Gena Gammie, Director, Water Initiative, Forest Trends

- Todd Gartner, Director of Cities4Forests and Natural Infrastructure Initiative, World Resources Institute (WRI)

- Colin Herron, Senior Water Resources Management Specialist, Water Solutions for the SDGs, Global Water Partnership

- George Kelly, CEO, Earth Recovery Partners

- Jim Lochhead, former CEO, Denver Water

- John H. Matthews, Executive Director, Alliance for Global Water Adaptation (AGWA)

- Alexis Morgan, Global Water Stewardship Lead, WWF

- Naabia Ofosu-Amaah, Senior Corporate Engagement Advisor, Water & Resilience, The Nature Conservancy

- James Salzman, Bren Distinguished Professor of Environmental Law, UCLA Law School and UCSB Bren School of Environmental Science & Management

- Daniel Shemie, Director, Resilient Watersheds, The Nature Conservancy

- Mia Smith, Program Manager, Water Initiative, Forest Trends

- Sophie Tremolet, Water Team Lead, OECD

- Paola Zavala, Programs Director, Fundación Futuro Latinoamericano (FFLA)

- James Dalton, Water Global Director, IUCN

- Gregg Brill, Associate Director, Accounting for Nature Program (Pacific Institute) & Technical Lead (CEO Water Mandate)

Please see our Reprint Guidelines for details on republishing our articles.

Search

RECENT PRESS RELEASES

Related Post