Global use of coal hit record high in 2024

October 21, 2025

Coal use hit a record high around the world last year despite efforts to switch to clean energy, imperilling the world’s attempts to rein in global heating.

The share of coal in electricity generation dropped as renewable energy surged ahead. But the general increase in power demand meant that more coal was used overall, according to the annual State of Climate Action report, published on Wednesday.

The report painted a grim picture of the world’s chances of avoiding increasingly severe impacts from the climate crisis. Countries are falling behind the targets they have set for reducing greenhouse gas emissions, which have continued to rise, albeit at a lower rate than before.

Clea Schumer, a research associate at the World Resources Institute thinktank, which led the report, said: “There’s no doubt that we are largely doing the right things. We are just not moving fast enough. One of the most concerning findings from our assessment is that for the fifth report in our series in a row, efforts to phase out coal are well off track.”

If the world is to reach net zero carbon emissions by 2050, in order to limit global heating to 1.5C above preindustrial levels, as set out in the Paris climate agreement, then more sectors must use electricity instead of oil, gas or other fossil fuels.

But this will work only if the global electricity supply is shifted to a low-carbon footing. “The trouble is that a power system that relies on fossil fuels has huge cascading and knock-on effects,” said Schumer. “The message on this is crystal clear. We simply will not limit warming to 1.5C if coal use keeps breaking records.”

Though most governments are supposed to be aiming to “phase down” coal use after a commitment made in 2021, some are pushing ahead with the most polluting fuel. India’s prime minister, Narendra Modi, celebrated surpassing 1bn tonnes of coal production this year, and in the US Donald Trump has declared his support for coal and other fossil fuels.

Trump’s efforts to halt renewable energy projects, and remove funding and incentives for switching to low-carbon power sources, have largely not made themselves felt yet in the form of higher greenhouse gas emissions. But the report suggested these efforts would have an effect in future, though others, including China and the EU, could blunt the impact by continuing to favour renewables.

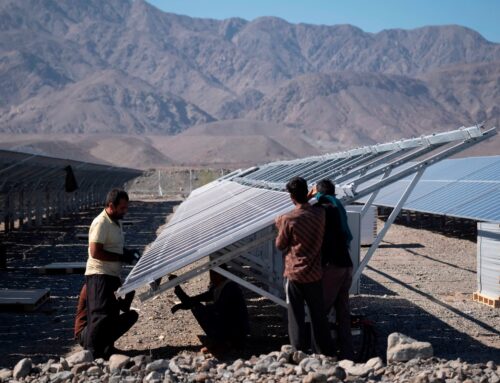

The good news is that renewable energy generation has grown “exponentially”, according to the report, which found solar to be “the fastest-growing power source in history”. This is still not enough, however: the annual growth rates of solar and wind power need to double for the world to make the emissions cuts needed by the end of this decade.

Sophie Boehm, a senior research associate at the WRI’s systems change lab and a lead author of the report, said: “There’s no question that the United States’ recent attacks on clean energy make it more challenging for the world to keep the Paris agreement goal within reach. But the broader transition is much bigger than any one country, and momentum is building across markets and emerging economies, where clean energy has become the cheapest, most reliable path to economic growth and energy security.”

The world is moving too slowly on improving energy efficiency, in particular cutting the carbon generated by heating buildings. Industrial emissions are also a concern: the steel sector has been increasing its “carbon intensity” – the carbon produced with each unit of steel manufactured – despite efforts in some countries to move to low-carbon methods.

Electrifying road transport is moving faster – more than one in five new vehicles sold last year was electric. In China, the share was closer to half.

The report also sounded a warning on the state of the world’s “carbon sinks” – forests, peatlands, wetlands, oceans and other natural features that store carbon. While nations have repeatedly pledged to protect their forests, they continue to be cut down, albeit at a slower rate in some areas. In 2024, more than 8m hectares (20m acres) of forest were permanently lost. That is lower than the high of nearly 11m hectares reached in 2017, but worse than the 7.8m hectares lost in 2021. The world needs to move nine times faster to halt deforestation than governments are managing, the report found.

World leaders and high-ranking officials will meet in Brazil next month for the Cop30 UN climate summit, to discuss how to put the world on track to stay within 1.5C of global heating in line with the 2015 Paris climate agreement. Each government is supposed to submit a detailed national plan on emissions cuts, called a “nationally determined contribution”. But it is already clear that those plans will be inadequate, so the key question will be how countries respond.

Search

RECENT PRESS RELEASES

Related Post