Green advocates urge Hong Kong to regulate ecotours and focus on conservation

January 4, 2026

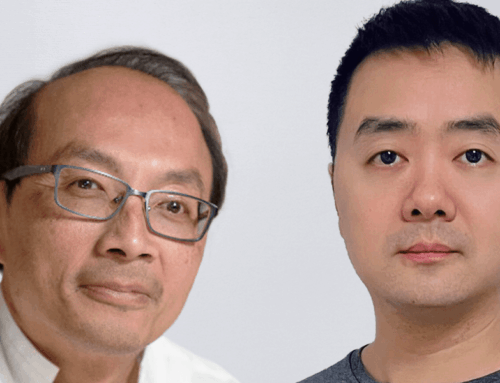

Last summer, Hong Kong environmental educator Yeung* led groups into the city’s mudflats. There, she saw the area overwhelmed by more than 200 people at a time.

Yeung is better known by her nickname, Sheeppoo. She kept her groups small to avoid disturbing the mudflats. These areas are key to Hong Kong’s biodiversity. But she noticed few others trying to respect the environment there.

Some visitors arranged sea stars for photos before tossing them back into the water. Being out of the water is stressful for these animals. Being touched by people can also be damaging.

“Even though these groups had leaders or guides, few offered reminders or tried to stop such behaviour,” said Yeung, who is in her 30s.

In recent years, more tourists have been interested in Hong Kong’s nature. But environmental advocates say the boom in ecotours is hurting wildlife.

In October, many people visited Sharp Island and damaged its coral reefs. Weeks later, hundreds of hikers went to see Sunset Peak’s seasonal silver grass.

On the weekend before the Christmas holiday, hundreds of campers went to Ham Tin beach. They left piles of litter outside a public toilet despite signs telling people to handle their own trash.

Even careful visitors could overwhelm an area, Yeung noted.

“Once numbers exceed what the environment can handle, harm becomes unavoidable,” she said.

Yeung added that this was why officials should study the number of people that an ecosystem could handle. Then, they could make rules to control the flow of visitors.

Hong Kong environmental educator Yeung*, better known as Sheeppoo, led guided groups into the city’s mangrove zones to observe mudflat ecosystems. Photo: Handout

Conservation first

Ha Shun-kuen is a Greenpeace campaigner. He believes ecotours should focus on protecting the ecosystems they visit.

“It’s not just tourism happening in nature. It has to respect and conserve the environment,” Ha said.

On land, it is easy to see the problems of overtourism: litter and widening trails. But under water, the damage could be far harder to understand.

Ha and Yeung said Sharp Island was a wake-up call to the harm when there are no rules for ecotours.

“Officials responded only after public outcry, offering on-site reminders and distributing leaflets,” Ha said. “That was far too little, too late.”

Ha pointed out that Sharp Island’s corals and beaches were not part of a marine park or country park. He said many of the city’s ecologically important sites are not protected by the law.

“If the government wants to prevent further loss, it must first identify ecologically sensitive areas lacking legal protection,” he said.

He encouraged the government to work with companies to form an ecotourism policy. They can make plans to manage visitors during popular seasons.

Tourists trampled corals around Sharp Island during the “golden week” holiday. Photo: Handout

How Hong Kong can do better

Ha noted the importance of conservation in Beijing’s ecotourism plan issued in 2016. “Hong Kong shouldn’t lag behind national standards,” he said.

Many countries also create special zones where ecological areas must be protected and where they can handle many visitors.

“Hong Kong needs a similar planning mindset,” Ha said.

The campaigner added that Hong Kong needed more long-term education efforts.

Yeung recalled seeing pupils leave rubbish along a hiking trail.

“Teachers might ask them to clean up at the end, but by then, some rubbish has already blown into the ravine,” Yeung said. “Awareness has to begin before the outing even starts.”

* Full name withheld at interviewee’s request.

Search

RECENT PRESS RELEASES

Related Post