How bitcoin drives cheap green energy production in Kenya

April 1, 2025

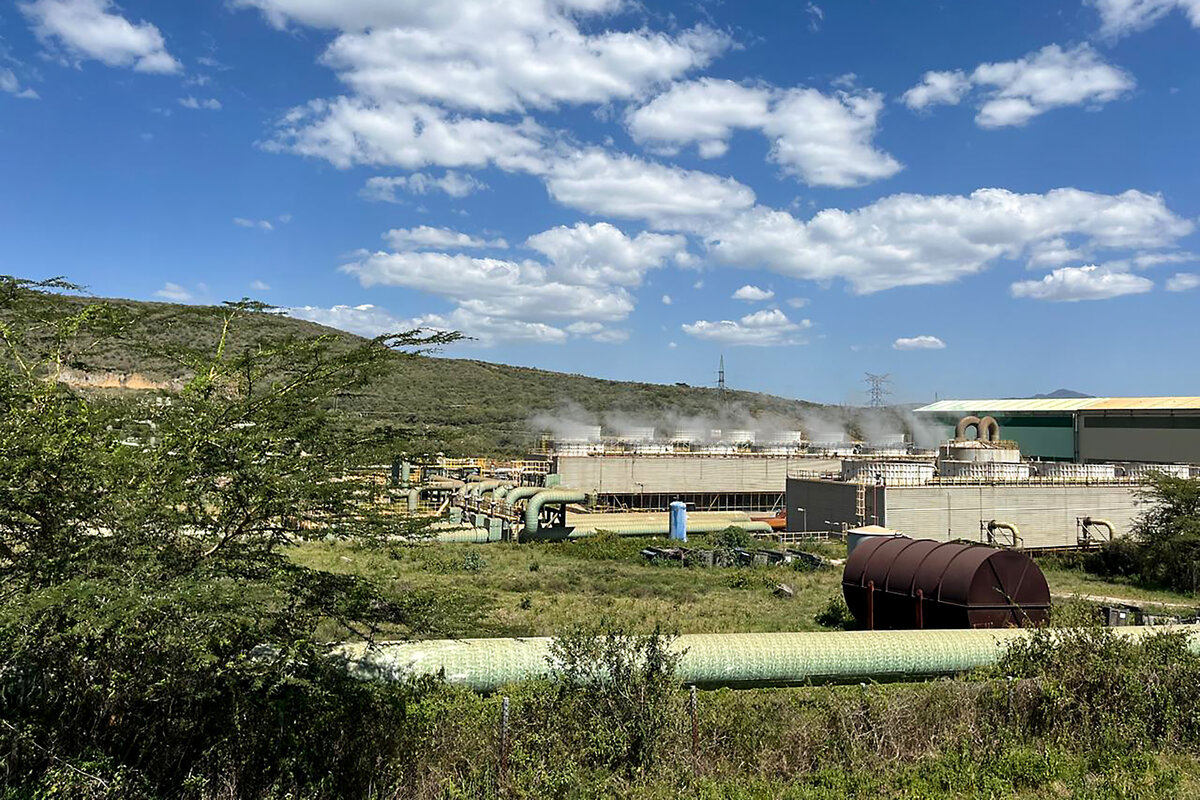

Beneath grassy plains where zebras and warthogs roam, the tectonic plates of the Rift Valley are slowly breaking apart. In a few million years, this place will likely be an ocean. For now, though, all that underground activity makes it an ideal source of energy. Almost too ideal.

“We have more generation than we can use,” says Fredrick Apollo, plant manager at a local geothermal power plant, run by the Oserian Development Co.

Enter an improbable solution – bitcoin mining. Cables snake from the power plant to an aluminum shipping container a few miles away. There, five dozen shoebox-sized machines whir day and night, sucking up electricity that Oserian would otherwise discard to make new units of the cryptocurrency.

Bitcoin mining requires a notoriously large amount of electricity, as much as the country of Poland uses. Only about a third of that energy comes from renewables or nuclear.

In an effort to change that, and to find new sources of cheap energy, more cryptocurrency mining companies are setting up shop next to sources of renewable energy. They sponge up the excess energy that, unlike fossil fuels, can be difficult to stockpile or transport.

That is also an attractive proposal for struggling renewable power providers, though experts warn it is only a short-term solution to their storage woes. But in Africa, where the focus is on generating electricity in the first place, cryptocurrency miners are unexpectedly filling a gap.

An energy puzzle

The 500-kilowatt shipping container mine at Lake Naivasha is tucked away off a dirt road just outside Hell’s Gate National Park, whose towering cliffs and rocky gorges inspired “The Lion King” movie.

The neat rows of machines inside are hot to the touch, a clue to the energy-guzzling demands of bitcoin creation.

Bitcoin is born when computers around the world race to solve complicated math puzzles whose solutions help secure the bitcoin network. Whoever finds the answer to one of these puzzles first is rewarded with bitcoin, whose value has soared from less than $1,000 in 2016 to over $80,000 at the time of writing.

When the network began in 2009, anyone with a computer could mine bitcoin. As more people joined in, the puzzles got harder. Miners had to use more and more sophisticated machinery, requiring more and more energy.

As a result, most bitcoin mining now happens in gargantuan warehouses in places where energy is abundant and cheap, like Texas and Kazakhstan. But the company that runs the Kenyan mine, Gridless, sees an opportunity to use mining’s vast appetite for power to drive the development of renewable energy in rural Africa. The startup, which is backed by Twitter co-founder Jack Dorsey, strikes deals with companies like Oserian to buy power that they are already producing but cannot sell.

That situation is common in many African countries, where renewable energy is abundant but energy infrastructure is poor. Some 600 million people on the continent, nearly half the population, have no electricity. But power grids are expensive to set up, and even where they exist, there are not always enough customers who can afford to pay.

Globally, power grids often rely on big industrial customers to stay afloat, says Erik Hersman, CEO and co-founder of Gridless, which operates six sites in Kenya, Malawi, and Zambia. “You don’t have those here,” he points out.

Thinking long-term

For Oserian, Gridless’ pitch was intriguing. The mining computers would sponge up energy when there was extra and shut off when demand from other customers was high, helping keep the grid stable. As payment, Oserian would receive some of the bitcoin mined.

Though bitcoin is a volatile currency, some studies have shown that extra income from bitcoin mining can help renewable energy providers scale up. In Ethiopia, home to some of the cheapest green energy in the world, nearly a fifth of all electricity sold in the country last year went to bitcoin mining companies. The income will help develop the national grid.

Gridless says that it, too, is helping expand access to renewable energy. For instance, in a remote part of southern Malawi, Gridless set up shop in a community running a micro-hydropower system. Once it began mining, the station could afford to provide electricity for 500 more households. Another hydropower site in Kenya lowered prices by nearly a third.

Not all the signs are so promising, though.

Renewable energy will only really be able to replace fossil fuels when the technology exists to store and transport it. But energy companies selling to bitcoin miners next door do not have to find ways to store it, says Jona Stinner, a postdoctoral researcher at Witten/Herdecke University in Germany who studies the environmental impact of bitcoin mining. So there is no incentive to develop novel storage facilities.

It is “not very helpful for the long-term green transformation,” Mr. Stinner says.

Still, the fans in the computers at Gridless’ mine near Lake Naivasha continue to hum, drowning out the chirping of birds and the cries of baboons. As long as there’s extra electricity to be had here, the company sees no reason to turn them off.

Search

RECENT PRESS RELEASES

Related Post