How Meta made fraud look smaller without making it go away

January 8, 2026

Meta has a problem. Fraudulent ads that flood Facebook and Instagram, and siphon billions of dollars from users, have drawn the attention of regulators and lawmakers around the world over the past year. Authorities are now seeking to force the company to reduce them.

Meta’s response, according to a Reuters investigation, was not to meaningfully cut the volume of such ads, doing so would have jeopardized a major revenue stream, but to create the appearance of progress. The company did so by selectively reducing the visibility of fraudulent ads in the specific tools regulators use to monitor them. The result, Reuters reported, was that Meta managed to deflect regulatory pressure, stall new rules, and protect tens of billions of dollars in advertising revenue, while victims continued to fall prey to scams operating on its platforms.

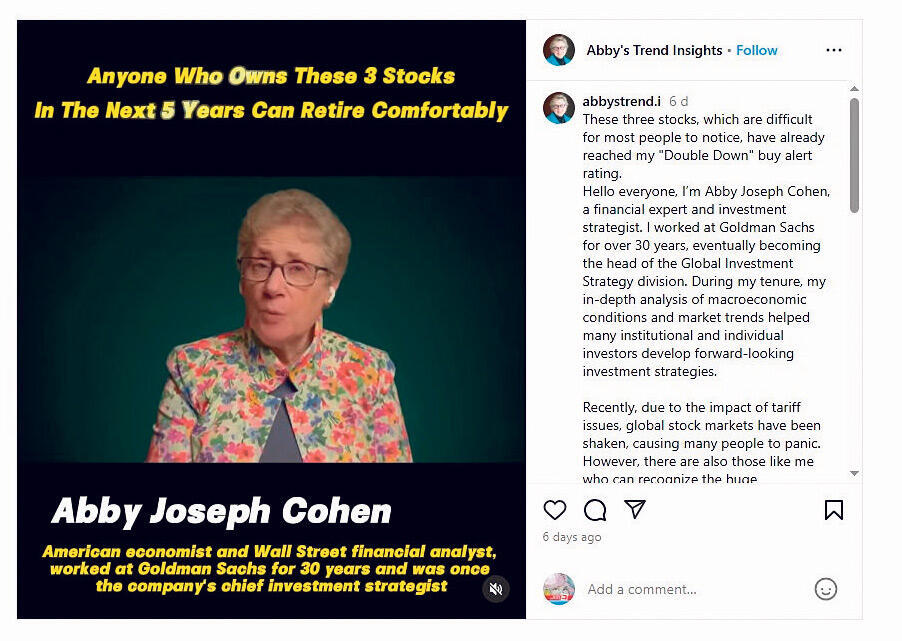

Among the most common schemes are ads using deepfakes of well-known economists and investors, luring users into WhatsApp groups with promises of stock tips. In reality, these groups are part of “pump-and-dump” schemes, in which false information is used to inflate the price of a security before insiders sell, leaving ordinary investors with losses.

According to the Israeli Internet Association, 57% of complaints it receives about fraud or scams are linked to Meta platforms. In November, it was revealed that in 2024 ads related to investment scams, illegal gambling, and prohibited products accounted for roughly 10% of Meta’s global revenue. Against that backdrop, the company’s reluctance to aggressively clamp down on fraud is easier to understand.

Regulators have begun exploring ways to compel Meta to act. In Israel, the Securities Authority has warned that it may pursue legislation obligating the company to combat fraud if Meta does not do so adequately on its own. In Japan, regulators also grew alarmed at the scale of scams on Facebook and Instagram and considered rules that would have required Meta to verify every advertiser, a move that would likely have reduced fraud substantially but also harmed advertising revenue, including from legitimate businesses.

Related articles:

According to Reuters, Meta responded by taking steps designed to reduce the exposure of fraudulent ads specifically to Japanese regulators. The primary tool regulators use to monitor such ads is Meta’s ad library, a public, searchable database meant to increase transparency by allowing users to view ads shown on the platform.

Internal documents reviewed by Reuters show that Meta understood Japanese regulators were using the ad library as a “simple test” of the company’s effectiveness in combating fraud. To perform better on that test, Meta employees devised a way to manage what they internally called the “circulation perception” of fraudulent ads within the library.

The company compiled lists of keywords and celebrity names commonly used by regulators to detect scams. Meta then repeatedly ran searches using those terms and removed fraudulent ads that appeared in the results. “We have identified a new ‘ad discovery’ metric that identifies the regulatory risk associated with an external agent being able to easily find fraudulent ads in the ad library,” one internal document stated. “This is a simple test that regulators often use to form an opinion on Meta’s effectiveness in combating fraud.”

The tactic worked, narrowly. The number of fraudulent ads surfaced through those specific searches dropped sharply. “We detected fewer than 100 ads last week, and we’ve reached zero in the past four days,” one document noted. But the broader impact on overall fraud was likely minimal. Keyword searches uncover only a small fraction of ads, and scammers can easily adjust language and tactics to evade detection.

Still, the move achieved its primary objective: easing regulatory pressure in Japan. “The number of fraudulent ads is decreasing,” a member of Japan’s ruling party told local media. The government subsequently decided not to advance advertiser-verification rules.

2 View gallery

Fake video: Prof. Abby Joseph Cohen from the Columbia University School of Business Administration

(screenshot)

Following that success, Meta expanded the approach as it faced similar scrutiny in the United States, the European Union, India, Australia, Brazil, and Thailand.

Meta has strong financial incentives to resist mandatory advertiser verification. Internal documents show that in 2024, only 55% of Meta’s advertising revenue came from verified advertisers. The company says that figure has since risen to 70%, but full verification could still threaten up to 30% of revenue, tens of billions of dollars annually. At the same time, Meta’s own analyses show that unverified advertisers account for the majority of fraudulent ads. One internal review from 2022 found that 70% of new advertisers promoted scams, illegal goods, or low-quality products.

At present, only Taiwan and Singapore require Meta to verify advertisers. According to company documents, those rules led to an immediate 29% drop in fraudulent ads. However, Meta found a way to limit the financial impact: when unverified advertisers are blocked in one country, their ads are redirected to users elsewhere.

Meta denied wrongdoing. “It would be dishonest to imply otherwise,” the company said in response to Reuters. “When we remove ads from search results, we also remove them from the system.” Meta also claimed that user reports of fraud have fallen by 50% over the past year and said it had set “aggressive goals” to reduce fraud in the most affected countries.

Meta’s bet appears straightforward: even if regulators eventually force real changes, the penalties are unlikely to outweigh the profits generated in the meantime. Only severe financial sanctions would alter that calculus, and fines on that scale remain improbable.

Search

RECENT PRESS RELEASES

Related Post